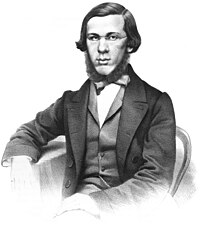

Nikolay Dobrolyubov

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Nikolay Dobrolyubov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Добролю́бов |

| Born | 5 February 1836 Nizhny Novgorod, Nizhny Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 29 November 1861 (aged 25) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Genre | Literary criticism, journalism, poetry |

| Years active | 1854–1861 |

| Signature | |

Nikolay Alexandrovich Dobrolyubov (Russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Добролю́бов, IPA: [nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ dəbrɐˈlʲubəf] ; 5 February [O.S. 24 January] 1836 – 29 November [O.S. 17 November] 1861) was a Russian poet, literary critic, journalist, and prominent figure of the Russian revolutionary movement. He was a literary hero to both Karl Marx and Lenin.[1]

Biography

[edit]Dobrolyubov was born in Nizhny Novgorod, where his father was a poor priest.

He was educated at a clerical primary school, then at a seminary from 1848 to 1853. His teachers in the seminary considered him a prodigy, and at home he spent most of his time in his father's library, reading books on science and art. By the age of thirteen he was writing poetry and translating verses from Roman poets such as Horace.[2] In 1853 he went to Saint Petersburg and entered the Saint Petersburg Main Pedagogical Institute.[3] Following the deaths of each of his parents (March and August 1854), he assumed responsibility for his brothers and sisters. He worked as a tutor and translator in order to support his family and to continue his studies. His heavy workload and the stress of his position had a negative effect on his health.[4]

During his tertiary education (1853 to 1857)[5] Dobrolyubov organized an underground democratic circle,[citation needed] issued a manuscript newspaper,[6] and led the students' struggle against the reactionary educational administration.[citation needed] His poems On the 50th Birthday of N. I. Grech (1854), and Ode on the Death of Nicholas I (1855), copies of which were distributed outside the institute, showed his hostile attitude toward the autocracy.[4][7]

In 1856 Dobrolybov met the influential critic Nikolay Chernyshevsky and the publisher Nikolay Nekrasov. He soon began publishing his works in Nekrasov's popular journal Sovremennik. In June 1857, after his graduation from the Pedagogical Institute, he joined the staff of Sovremennik and soon became head of its Book Review section.[8] Over the next four years, he produced several volumes of important critical essays. One of his best-known works was his essay What is Oblomovism?,[9] based on his analysis of the 1859 novel Oblomov by Ivan Goncharov.[4][7][10]

In May 1860, at the insistence of friends, he went abroad in an effort to treat incipient tuberculosis, which had been exacerbated by overwork. He lived in Germany, Switzerland, France, and for more than six months in Italy, where the national liberation movement, led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, was taking place. The situation in Italy provided him with material for a series of articles.[4]

He returned to Russia in July 1861. He died in November 1861, at the age of twenty-five, from acute tuberculosis. He was buried next to Vissarion Belinsky at Volkovo Cemetery in Saint Petersburg.[7]

English translations

[edit]

- What is Oblomovism?, from Anthology of Russian Literature, Part 2, Page 272, Leo Weiner, G.P. Putnam's Sons, NY, 1903. from Archive.org

- Selected Philosophical Essays, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1956.

- Belinsky, Chernyshevsky & Dobrolyubov: Selected Criticism, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1976.

References

[edit]- ^ Soviet Calendar 1917-1947: CCCP production

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana, Vol 9, The Encyclopedia Americana Corporation, NY, 1918.

- ^ Zilbergerts, Marina (5 April 2022). The Yeshiva and the Rise of Modern Hebrew Literature. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780253059413. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

Dobrolyubov, whose father strictly prohibited him from enrolling in a university, traveled to St. Petersburg with the assumed intent of joining the Theological Academy. He enrolled, instead, at St. Petersburg's Main Pedagogical Institute.

- ^ a b c d Russian Literature, Peter Kropotkin, McClure Phillips, NY, 1905.

- ^ Kruzhkov, Vladimir Semyonovich (1954). The Socio-political and Philosophical Views of N. A. Dobrolyubov. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. p. 4. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

N. A. Dobrolyubov's life and activities can be divided into three periods. [...] The second was the period of his education at the Central Pedagogical Institute in St. Petersburg (1853-1857).

- ^ Posin, Jack Abrahim (1939). Chernyshevsky, Dobrolyubov, and Pisarev, the Ideological Forerunners of Bulshevism. University of California, Berkeley. p. 196. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

[...] towards the end of 1855 he began to edit a manuscript journal called Rumors, which he humorously described as 'a newspaper literary, anecdotic, and only partly political'.

- ^ a b c The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970-1979). © 2010 The Gale Group, Inc.

- ^ Kruzhkov, Vladimir Semyonovich (1954). The Socio-political and Philosophical Views of N. A. Dobrolyubov. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. p. 5. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

In June 1857, on graduating from the Pedagogical Institute, he became a member of the staff of the Sovremennik and at the end of that year was put in charge of its Book Review section.

- ^ Что такое обломовщина? : Обломов. Роман И. А. Гончарова. «Отечественные записки», 1859 г., № I—IV

- ^ Anthology of Russian Literature, Part 2, Leo Weiner, G.P. Putnam's Sons, NY, 1903.

External links

[edit]- A poem by Dobrolyubov- Death's Jest

- Dobrolyubov Memorial Museum