1961 Philadelphia municipal election

| Elections in Pennsylvania |

|---|

|

| |

Philadelphia's municipal election of November 7, 1961, involved the election of the district attorney, city controller, and several judgeships. Democrats swept all of the city races but saw their vote totals much reduced from those of four years earlier, owing to a growing graft scandal in city government. District Attorney James C. Crumlish, Jr. and City Controller Alexander Hemphill, both incumbents, were returned to office. Several ballot questions were also approved, including one permitting limited sales of alcohol on Sundays.

Background

[edit]

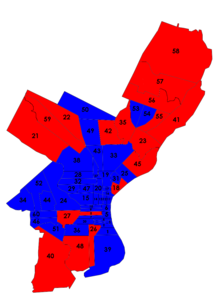

In 1957 and 1959, Philadelphia Democrats had achieved citywide victories over the Republicans, capping a string of electoral wins that had begun in 1951.[1] Their 1959 victory, especially, indicated a complete domination of the city's politics as Mayor Richardson Dilworth carried 58 of 59 wards in his reelection bid; he and other Democrats running for citywide seats took nearly two-thirds of the vote.[1] It was followed up by a resounding success in the presidential election of 1960, when Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy carried the state thanks to a 330,000-vote majority in Philadelphia.[2] The coalition of independent reformers and organization Democrats looked to further increase their success in 1961, with Democratic City Committee chairman William J. Green, Jr., predicting a margin of 100,000 votes in the off-year election.[2]

As the election neared, however, some cracks began to show in the Democrats' dominance. Dilworth held a neighborhood meeting to announce a plan to charge for parking in South Philadelphia, and was pelted with rocks and garbage in a near-riot.[3][4] Even more embarrassing to a party that had been elected on a platform of reform was an investigation that year into political corruption and bribery in City Hall.[3] Republicans demanded that a grand jury be convened to investigate further, but Judge Raymond Pace Alexander (who had served as a Democratic city councilman from 1952 to 1959) rejected their petition.[3] While Green asked voters for "indorsement for continuance in office on solid accomplishments," Republican City Committee chairman Wilbur H. Hamilton drew attention to the scandals and called the erstwhile reform movement a "broken idol" that "promised much and delivered little."[5]

District Attorney

[edit]

Philadelphia elects a district attorney independently of the mayor, in a system that predates the charter change.[6] Since 1957, district attorney elections have followed mayoral and city council elections by two years.[7] In that year, Philadelphians reelected Victor H. Blanc as District Attorney of Philadelphia by a thirteen-percentage-point margin. Three years later, Governor David L. Lawrence appointed Blanc to the court of common pleas.[8] Blanc's first assistant, Paul M. Chalfin, served as acting district attorney while the common pleas judges decided on a replacement who would serve until the 1961 election.[9] The fight for the interim post became a battle between political factions with Green's preferred candidate, James C. Crumlish, Jr., getting the judges' approval in March 1961. Crumlish ran for a full four-year term that fall.[9]

Republicans nominated Theodore B. Smith, Jr., a former assistant district attorney who had been in private practice since 1958, without primary opposition.[10][11] Smith and the Republicans accused Crumlish of being a tool of the Democratic party machine and said that he covered up corruption in the graft investigation.[12] Democrats were confident of an easy victory for Crumlish, but he won by just 47,000 votes. The margin was far less than expected and the worst showing for Democrats in a district attorney contest since 1947.[2] Crumlish trailed all citywide Democratic candidates, which The Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Joseph C. Goulden attributed to the growing perception of corruption in the party, and in the district attorney's office in particular.[13]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | James C. Crumlish, Jr. | 335,806 | 53.90 | −2.33 | |

| Republican | Theodore B. Smith, Jr. | 287,252 | 46.10 | +2.33 | |

City Controller

[edit]Philadelphia elects a City Controller to sit at the head of an independent auditing department. The Controller approves all payments made out of the city treasury and audits the executive departments.[15] As an independently elected official, the Controller is not responsible to the mayor or the city council.[15] The office was created under the 1919 City Charter and later given expanded powers as one of the good-government reforms intended to reduce the corruption that had previously plagued city government and led to the reform coalition of 1951.[15]

Democrat Alexander Hemphill had been elected to the office in 1957 and ran for reelection. He was a lawyer with a long history of involvement in Democratic politics who had worked with reformers in the campaigns that ultimately defeated the Republican organization in 1951. Hemphill was the organization's nominee in 1957, but often clashed with Dilworth and others. His investigation had brought to light the initial evidence leading to the graft charges against members of his own party.[11]

Hemphill's opponent was Joseph C. Bruno, a West Philadelphia lawyer, who fended off a surprisingly strong primary protest vote for Joseph A. Schafer, an accountant from Northeast Philadelphia.[10] Despite Hemphill's investigation into the alleged misconduct, the Democratic Party's scandals reduced his totals as well, though still giving him a 55,000-vote victory over Bruno.[12] Hemphill continued in office until 1967, when he resigned to run for mayor.[16]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Alexander Hemphill | 340,164 | 54.54 | −2.42 | |

| Republican | Joseph C. Bruno | 283,583 | 45.46 | +2.42 | |

Judges and magistrates

[edit]Although Pennsylvania's judges are elected in partisan elections, there had been a tradition of not challenging the re-election of incumbents. To that end, judicial candidates were typically endorsed by both major parties but in 1953 Democrats broke the informal pact and endorsed just three of the sitting judges, resulting in an unusually intense contest.[17] By 1957, the old order was mostly re-established as all but one of the sitting judges were endorsed for re-election by both parties and returned to office without opposition.[18]

In 1961, four common pleas court judges and two orphans' court judges were on the ballot, and all were cross-endorsed in accordance with the sitting-judge principle.[11] All were reelected to ten-year terms, including Victor H. Blanc, the former district attorney.[19]

There were also seven seats open for magistrate, a local court, the duties of which have since been superseded by the Philadelphia Municipal Court. In the magistrate races, a limited voting law meant that each political party could nominate four candidates, and voters could only vote for four, with the result being that the majority party could only take four of the seven seats, leaving three for the minority party.[11] The Democrats took the maximum number of four magistracies, with all four of their incumbents being reelected, led by Harry C. Schwartz.[20] The remaining three seats went to Republicans, with one spot going to the only GOP incumbent on the ballot, Thomas A. Connor.[20] The other two Republicans elected were 42nd Ward leader John P. Walsh and former police captain Luke A. McBride, who edged out court stenographer George J. Woods.[20]

Ballot questions

[edit]At the May primary, two referendums were proposed; the first would permit Sunday alcohol sales in hotels that had liquor licenses, the second would borrow $10 million for school construction. Both passed, gathering 67.6% and 75.9% of the vote, respectively.[21] In November, five more questions were on the ballot, all asking the voters' permission to borrow money for various infrastructure improvements.[11] All five, approving a total of $65 million in loans, passed by a two-to-one margin.[22]

Aftermath

[edit]The 1961 election confirmed the Democrats in power, but their reduced margins and increased association with machine politics signaled the beginning of the end for the party's coalition with independent good government reformers.[23] Dilworth, in particular, saw the election as a warning sign, telling the party that they must "watch your Ps and Qs" to avoid further setbacks.[24] Even so, Green's control over federal patronage through the Kennedy administration and Dilworth's resignation in 1962 to run for governor left the Democratic Party fully in the hands of the ward leaders.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Freedman 1963, pp. II–31–II–33.

- ^ a b c Inquirer 1961f.

- ^ a b c Freedman 1963, p. II–32.

- ^ Goulden, Thomas & Collins 1961.

- ^ Green 1961; Hamilton 1961.

- ^ Freedman 1963, p. II–6.

- ^ Reichly 1959, p. 39.

- ^ Freedman 1963, p. II–33.

- ^ a b Freedman 1963, p. II–34.

- ^ a b Miller 1961, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Inquirer 1961a.

- ^ a b Goulden 1961, p. 1.

- ^ Goulden 1961, p. 4.

- ^ a b Bulletin Almanac 1962, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Committee of Seventy 1980, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Inquirer 1986.

- ^ Inquirer 1953.

- ^ Miller 1957.

- ^ Inquirer 1961c.

- ^ a b c Inquirer 1961d.

- ^ Miller 1961, p. 1.

- ^ Inquirer 1961e.

- ^ a b Freedman 1963, pp. II–51–II–52.

- ^ Inquirer 1961b.

Sources

[edit]Books

- Bulletin Almanac 1962. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Philadelphia Bulletin. 1962. OCLC 8641470.

- Freedman, Robert L. (1963). A Report on Politics in Philadelphia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Joint Center for Urban Studies of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University. OCLC 1690059.

- Reichly, James (1959). The Art of Government: Reform and Organization Politics in Philadelphia. New York, New York: Fund for The Republic. OCLC 994205.

Newspapers

- "Sitting Judge Policy 'Scrapped' By Democrats; GOP Offers Slate". The Philadelphia Inquirer. March 15, 1953. pp. 1, 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- Miller, Joseph H. (November 6, 1957). "Democrats Take Every Office in City". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Miller, Joseph H. (May 17, 1961). "Sunday Liquor Sales, School Bonds Voted; Greenlee Easy Victor". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Goulden, Joseph C.; Thomas, Robert; Collins, William (July 25, 1961). "Rock Barrage Imperils Dilworth As 2000 Protest His Parking Plan". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Nearly a Million Can Vote". The Philadelphia Inquirer. October 30, 1961. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Green, William J. (November 5, 1961). "Opposing Party Chiefs Both Predict Victory (1)". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hamilton, Wilbur H. (November 5, 1961). "Opposing Party Chiefs Both Predict Victory (2)". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- Goulden, Joseph C. (November 8, 1961). "Crumlish Draws Smallest Vote of Top City Winners". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Vote Warns Party To Mind Ps and Qs, Mayor Says". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 8, 1961. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Six Judges Win 10-Year Terms". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 8, 1961. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- "5 Incumbents Are Re-Elected as Magistrates". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 8, 1961. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Loan Questions in Phila. Gain 2-to-1 Approval". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 8, 1961. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- "GOP Resurgence: Green Setback". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 9, 1961. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Alexander Hemphill, 64; served as city controller". The Philadelphia Inquirer. January 31, 1986. p. 17-C – via Newspapers.com.

Report

- Committee of Seventy (1980). "The Charter: A History" (PDF). Philadelphia. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2017.