British currency in the Middle East

British involvement in the Middle East began with the General Maritime Treaty of 1820. This established the Trucial States and the nearby island of Bahrain as a base for suppressing sea piracy in the Persian Gulf. Meanwhile, in 1839 the British East India Company established an anti-piracy station in Aden to protect British shipping that was sailing to and from India. Involvement in the region expanded to Egypt in 1875 because of British interests in the Suez Canal, with a full scale British invasion of Egypt taking place in 1882. Muscat and Oman became a British Protectorate in 1891,[1] and meanwhile Kuwait was added to the British Empire in 1899 because of fears surrounding the proposed Berlin-Baghdad Railway. There was a growing concern in the United Kingdom that Germany was a rising power, and about the implications that the proposed railway would have as regards access to the Persian Gulf. Qatar became a British Protectorate in 1916, and after the First World War, the British influence in the Middle East reached its fullest extent with the inclusion of Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq.

Background

[edit]For nearly four hundred years, silver Spanish dollars (pieces of eight) had served as the international currency, and most of these coins were minted in Mexico City, Lima, and Potosí in the New World. Following the successful introduction in 1821 of a gold standard in the UK based on the gold sovereign, the policy of introducing the sterling currency into all of the British colonies began with an imperial Order in Council dated 1825,[2] when the source of the Spanish dollars was drying up following revolutions in Latin America.

In 1825, the British Empire had not as yet reached its widest extent. Following the American Revolution, Britain's attention switched to India, which was originally controlled by the British East India Company. The British government did not take direct control over India until after the Indian mutiny of 1857. Hence the imperial Order in Council of 1825 did not apply to India. As such, the already circulating silver rupee continued to be the currency of India for the entire duration of the British Raj, and afterwards into independence. The Indian rupee was not only the currency of India but also the currency of an extended region to its west, which stretched across the Indian Ocean to the east coast of Africa, up through the horn of Africa, through Aden and Muscat in Southern Arabia and Eastern Arabia, and along the Arabian coast of the Persian Gulf, extending even as far inland as Mesopotamia.[3]

Since the Middle East was a late addition to the British Empire, the British government had by then already learned from their experiences in places such as Canada, Ceylon, Mauritius, and Hong Kong that it is highly impractical to impose a new currency in the place of already existing ones. So, even though the pound unit of account eventually spread into the Middle East, the associated shillings and pence coinage never circulated there. This was the opposite of the situation in the Eastern Caribbean, where sterling shillings and pence coinage was used in conjunction with a Spanish dollar unit of account.[4]

Cyprus

[edit]The first territory in the Middle East to adopt the pound sterling unit of account was Cyprus. At the time of the occupation in 1878, for the purpose of paying the troops the British government instructed that a Turkish lira was to be rated at 9⁄10 of a pound sterling.[5] There was a complication, however, in that although one lira was equal to 100 Turkish piastres, this rate differed in practice between different locations. Furthermore, the copper piastre itself had depreciated relative to the silver piastre, such that in the bazaars one needed 175 copper piastres to buy a British gold sovereign. An additional problem was that gold coins were exported from Cyprus to Constantinople, where they could obtain an even greater amount of piastres than what was paid for them in Cyprus. Meanwhile, the Treasury pointed out that it would be unwise to introduce British shillings and pence, at once, as this would be seen as a foreign currency system. In order to solve these problems, the British government demonetised the debased Turkish piastres and introduced a new legal tender bronze British piastre at 180 to the gold sovereign. With this altered rating, the people made a profit when paying sovereigns into the treasury in settlement of their debts, and this reduced the incentive to ship the sovereigns to Constantinople. So, in 1879, after taking de facto control of Cyprus from the Ottoman Empire, The British introduced the pound sterling unit there at the rate of 180 bronze British piastres. Having deliberately avoided introducing shillings and pence, the new 9 piastre and 18 piastre coins did however correspond respectively in size and value to the shilling and florin coins in the UK. The pre-1879 para, at 40 para to the kuruş/piastre, continued as a unit of account appearing on postage stamps, but it was never seen on any coins or banknotes.[6][7]

The Cyprus Currency Board was established in 1927 and held the responsibility of administering the Cypriot pound.[8]

In 1947, the word shilling appeared for the first time on the 9 piastre and 18 piastre coins, but then in 1955, Cyprus adopted a decimal system, with 1,000 Mils in a pound. When the UK floated the pound sterling on 23 June 1972, some twelve years after Cyprus had obtained independence, the Cypriot pound began to diverge from the 1:1 parity it had maintained with the UK unit since its foundation in 1879.[9]

In 2008, Cyprus adopted the euro and the Cypriot pound ceased to exist.[10]

Palestine

[edit]

Following the institution of the British Mandate for Palestine in 1918, the Egyptian pound was introduced and it circulated alongside the Ottoman lira. Then in 1927, to end the confusion that had arisen as a result of the twin circulation of Turkish and Egyptian money in the territory, the British authorities established the Currency Board for Palestine, which introduced the Palestine pound, equal in value to the pound sterling, which was legal tender in Mandatory Palestine and in Transjordan.[11] The Palestine pound was not, however, used in conjunction with the normal sterling shillings and pence coinage. It was used with a decimal system in which it was divided into 1,000 mils.

The Currency Board was dissolved in May 1948, with the end of the British Mandate, but the Palestinian pound continued in circulation for a transitional period:

- Israel adopted the Israeli pound on 16 August 1948 at par with the Palestine pound, and meanwhile the 1:1 parity with the pound sterling continued until 1952, after which the external value of the Israeli pound began to drop rapidly.

- Jordan adopted the Jordanian dinar in 1949. The name dinar then became the preferred name for the pound sterling unit of account as it spread to other Middle East territories. The Jordanian dinar maintained its 1:1 parity with the pound sterling until 18 November 1967 when Harold Wilson devalued the pound. The Jordanian dinar did not devalue in parallel, hence breaking the sterling parity.

- In the West Bank, the Palestine pound continued to circulate until 1950, when the West Bank was annexed by Jordan, and the Jordanian dinar became legal tender there.

- In the Gaza Strip, the Palestine pound continued to circulate until April 1951, when it was replaced by the Egyptian pound, three years after the Egyptian army took control of the territory.

Arabia and Mesopotamia

[edit]Prior to British involvement in Arabia, Ottoman piastres and Maria Theresa thalers circulated in the region, with the thaler typically valued at 20 piastres.[12]

(The Maria Theresa thaler was a variety of the silver thaler coin first minted in Joachimsthal, Bohemia, in 1519, and known as the Joachimsthaler. The word "dollar" originates from the word Thaler, and due to the similarity between the German thalers and the slightly earlier Spanish eight real coin, the latter eventually became known in the English speaking world as Spanish dollars (or pieces of eight), these being the parent coins the modern US dollar.)

Then, with the arrival of the British in Aden in 1839, Indian rupees were introduced to the Arabian coast. British influence soon spread to the Gulf States, and the Indian rupee spread into those territories too. Later, during the First World War the Indian rupee also spread into Mesopotamia.[13]

On 22 January 1928, the Kingdom of Hejaz and Nejd introduced a new silver riyal loosely based on the Maria Theresa thaler but adjusted in weight slightly, so as to correspond in value exactly to a tenth of a British gold sovereign. In 1932, the Kingdom of Hejaz and Nejd became Saudi Arabia, and in 1936 the riyal was debased so as to correspond in weight and fineness to the Indian rupee.

Meanwhile, on 19 April 1931, Iraq, which had emerged as a British Mandate on the territory of Mesopotamia, adopted the Iraqi dinar at a 1:1 parity with the pound sterling, to replace the Indian rupee. This 1:1 parity with sterling continued until 18 November 1967 when Harold Wilson devalued the pound. Iraq did not follow suit and hence the parity was broken.

On 1 October 1951, the Indian rupee was replaced in Aden by the East African shilling, with twenty shillings being equal in value to one pound sterling. The East African shilling had itself been created in 1922 as a monetary unit out of the Indian rupee when the rising price of silver in the wake of the First World War caused the Indian rupees that circulated in British East Africa to rise in value to two shillings sterling. The East African shilling was launched at par with the shilling sterling at the value of half an Indian rupee.

In 1959, as a measure to prevent gold smuggling, the Reserve Bank of India and the Indian government, in conjunction with the British authorities, replaced the Indian rupee in the Gulf States with the Gulf rupee at a 1:1 parity.

1960s onwards

[edit]On 1 April 1961, Kuwait adopted a dinar unit at a 1:1 par with the pound sterling to replace the Gulf rupee, and it remained at this parity until 18 November 1967, when Harold Wilson devalued the pound sterling. As with the cases of the Jordanian dinar and the Iraqi dinar, Kuwait did not devalue in tandem, hence the 1:1 parity with the pound was broken that year.

On 1 April 1965, the South Arabian dinar replaced the shilling in Aden at twenty shillings to the dinar, and in this case, Aden did devalue in parallel with sterling on 18 November 1967, hence maintaining its 1:1 parity with sterling beyond the date of the British withdrawal from Aden, less than a fortnight later. [14] The South Arabian dinar was then renamed the South Yemeni dinar, and meanwhile it continued the 1:1 parity with sterling, at least into 1971, after which information about its value becomes hard to find, but by 1983, it had already diverged considerably from the sterling parity. The divergence probably began in June 1972 when the UK floated the pound sterling, because figures in the 1983 Financial Times "World Value of the Pound" suggest that the South Yemeni dinar had probably followed a similar course to that of the Omani riyal nearby. The South Yemeni unit eventually ceased to exist when South Yemen united with North Yemen in 1990.

On 1 October 1965, Bahrain replaced the Gulf rupee with a Bahraini dinar unit at fifteen shillings sterling. This rose to seventeen shillings and sixpence against the pound on 18 November 1967 when Bahrain did not devalue with the pound sterling.

In 1966, India devalued the rupee, prompting Qatar, Dubai, and all the Trucial States with the exception of Abu Dhabi, to introduce a new riyal unit at par with the pre-devaluation rupee. Abu Dhabi instead chose to adopt the Bahraini dinar, and in 1973 it changed to the United Arab Emirates dirham in line with the rest of the sheikdoms in the UAE.

On 7 May 1970, the Sultanate of Oman replaced the Gulf rupee with the Omani rial unit that was created at par with the pound sterling, so ending the existence of the Gulf rupee. Two years later, after the pound sterling was allowed to float on 23 June 1972, the Omani rial began to diverge from its sterling parity.

Summary

[edit]In summary, the currency units used in Israel, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, and the Yemen are all descended from the pound sterling unit, and the Bahraini dinar partially so, whereas the currency unit that was first used in Qatar and Dubai in 1966 replaced the Indian rupee at its pre-devaluation exchange rate. Meanwhile, during this same period, the pre-devaluation rupee just happened to be very close to par with the riyal of Saudi Arabia, which was even used in Qatar and Dubai on a temporary basis, prior to their new currency being ready. And although a near parity has carried on to the present day with respect to the Saudi riyal, the Qatari riyal, and the United Arab Emirates dirham, it is actually only the Saudi riyal that is descended from the Maria Theresa Thaler.

Egypt

[edit]

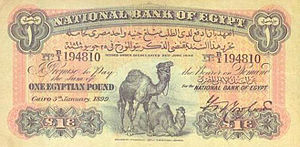

At the beginning of the 19th century, Egypt and Turkey shared a common currency, the Ottoman piastre, divided into 40 paras. However, under Muhammad Ali, Egypt started to issue its own coinage, and in 1834, by when Egypt was nominally independent from Ottoman rule, a khedival decree was issued, adopting an exclusively Egyptian monetary system whereby Egypt went into a silver and gold bimetallic standard based on the Maria Theresa thaler rated at 20 piastres. The Maria Theresa thaler was a popular silver trade coin in the region around that time.[15] In the wake of this currency reform, Egypt minted a gold coin known as the bedidlik, equal to 100 piastres, and a silver rial coin of 20 piastres corresponding to the Maria Theresa Thaler. In 1839, a piastre contained 1.146 grams of silver, and meanwhile the British gold sovereign was rated at 97.5 piastres. While 100 Egyptian piastres and the bedidlik coin were referred to as a "pound" in the English-speaking world, this was not the principal unit in the new Egyptian monetary system of 1834. Reference to an Egyptian pound unit of account appeared in 1884 on a £E50 promissory note signed by General Gordon at the Siege of Khartoum, but it was not until the next year, 1885, that this unit of account would become the official unit.

Meanwhile, back in 1840, despite Egypt's separate coinage, it was agreed under the Turkish-Egyptian treaty dated that same year, that coins struck in Turkey and Egypt should nevertheless maintain equal value. However, in 1844, the Ottoman piastre was devalued in conjunction with the creation of a new Ottoman lira unit, but Egypt did not follow suit. Hence the Egyptian and Turkish units split from each other in value, with the Egyptian unit continuing its exchange value of 97.5 piastres to the pound sterling.

In 1885, Egypt went into a purely gold standard, and the Egyptian pound unit, known as the juneih, was introduced at £E1 = 7.4375 grammes of fine gold. This unit was chosen on the basis of the gold content in the British gold sovereign and maintaining the exchange value of 97.5 piastres to the pound sterling, and it replaced the Egyptian piastre (qersh) as the chief unit of currency. This reform resulted in the Maria Theresa Thaler being adjusted to 21 piastres, with 20 piastres now being rated at 5 French francs, and the foreign exchange rates were fixed by force of law for the important currencies which had become acceptable in the settlement of internal transactions. But it was not until 1899 that banknotes started to appear with the word "pounds" on them, written in English. Meanwhile, the piastre continued to circulate as 1⁄100 of a pound, the para was discontinued in 1909, and the piastre was divided into tenths (عشر القرش 'oshr el-qirsh). These tenths were renamed milliemes (malleem) in 1916.

Then, at the outbreak of World War I, with the gold specie standard being suspended in the UK, the Egyptian pound used a sterling peg of one pound and sixpence sterling to one Egyptian pound. Inverted, this gives approximately £E0.975 for one pound sterling.

This exchange value of 97.5 piastres to the pound sterling continued until the early 1960s when Egypt devalued slightly and switched to a peg to the United States dollar, at a rate of E£1 = US$2.3.

The Egyptian pound continued with its exchange rate of £E = £1 0s 6d sterling until the beginning of the 1960s.

Use of Egyptian pound outside of Egypt

[edit]As well as in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, the Egyptian pound spread into two other neighbouring territories. From 1918 to 1927, it was legal tender in Mandatory Palestine where it circulated alongside Turkish coins.[17][18] This practice, however, ended in 1927 when the Palestine pound was established. Then later, between 1942 and 1951, when Cyrenaica was under British occupation, the Egyptian pound circulated alongside the Tripolitanian lira.

Libya

[edit]

When Libya was a part of the Ottoman Empire, the country used the Ottoman piastre, with Tripoli issuing some coins locally between 1808 and 1839.[19] Then in 1911, when Italy took over the country, the Italian lira was introduced. Thirty-two years later in 1943, as a result of Italy being driven out of Libya by the Allies of World War Two, the region was split into Free French and British mandate territories. Algerian francs were used in the Free French mandate. Meanwhile, in the British mandate, the military authorities issued the Tripolitanian lira which circulated alongside the Egyptian pound.

In 1951, the Libyan pound was introduced, replacing the franc and lira at rates of £L1 = 480 lire = 980 francs, and was equal in value to one pound sterling.[20] When sterling was devalued in 1967, the Libyan pound did not follow suit, so one Libyan pound became worth £1 3s. 4d. sterling. The Libyan pound was replaced by the dinar at par in 1971 following the Libyan Revolution of 1969.

Sudan

[edit]The Egyptian pound also circulated in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. However, in 1956 the Sudan became independent, and on 8 April 1957, the Egyptian pound was replaced at par with the Sudanese pound. During the 1960s, the Sudanese pound diverged in value from the Egyptian pound, and from 30 December 1969 through until 21 September 1971, the Sudanese pound was pegged at 1:1 parity with the pound sterling. This parity with sterling was not however reflected on the black market.[21]

Sterling area

[edit]At the outbreak of the Second World War, the sterling area was formed as an emergency measure to protect the external value of the pound sterling, mainly against the US dollar. All the territories mentioned above joined the sterling area since their respective pounds, dinars, shillings, or rupees were pegged at a fixed value to the pound sterling. The Indian rupee at that time was pegged to the pound sterling at a fixed value of one shilling and six pence sterling. In the years after the war, Egypt and Sudan, (1947), Israel, (1948), and Iraq, (1959), left the sterling area. Meanwhile, Libya was expelled in 1971.[22]

As a result of the sterling devaluation of November 1967, the floating of the pound sterling in June 1972, and the ending of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates that was introduced in 1944, none of the currencies mentioned above retain any fixed parity to any of the sterling units of account. Today there is no visible relationship between these currencies and the currency of the United Kingdom.

See also

[edit]- British currency in Oceania

- British currency in the South Atlantic and the Antarctic

- British currency in West Africa

- East African shilling

- Old Israeli shekel

- Palestine pound

- South Yemeni dinar

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/online-exhibitions/an-enduring-relationship-a-history/a-history-of-oman/ A History of Oman, Royal Air Force Museum

- ^ Robert Chalmers. "A History of Currency in the British Colonies" (1893), page 23.

- ^ https://www.cato.org/commentary/another-junk-currency-iraqi-dinar-bites-dust [bare URL]

- ^ Bank of Canada https://www.bankofcanadamuseum.ca/collection/artefact/view/1971.0101.00262.000/trinidad-royal-bank-of-canada-20-dollars-january-2-1920

- ^ Robert Chalmers. "A History of Currency in the British Colonies" (1893) page 325.

- ^ Numista https://en.numista.com/catalogue/chypre_section-1.html

- ^ https://www.rpsl.org.uk/rpsl/Displays/Handouts/DISP_20160218_001.pdf page 27

- ^ "Currency Matters: What Currency is in Cyprus Today?".

- ^ Investopedia https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cyp.asp

- ^ Financial Source https://financialsource.co/cyprus-pounds-cyp/#:~:text=Conversion%20to%20Euro&text=On%20January%201%2C%202008%2C%20Cyprus,economic%20stability%20within%20the%20Eurozone.

- ^ William F. Spalding. "Dictionary of the World's Currencies and Foreign Exchanges" Sir I. Pitman & sons, Limited, page 148/149.

- ^ Markus A. Denzel (2010). Handbook of World Exchange Rates, 1590-1914. Ashgate Publishing. p. 599. ISBN 978-0-7546-0356-6. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

The piastre of 1839 contained 1.146 grammes of fine silver, the piastre of 1801 approximately 4.6 grammes of fine silver. The most important Egyptian coins, the bedidlik in gold (= 100 piastres; 7.487 grammes of fine gold) and the rial in silver (20 piastres; 23.294 grammes of fine silver)

- ^ Franz Pick-Rene Sedillot. "All The Monies of the World - A Chronicle of Currency Values" Pick Publishing Corporation, New York, page 482 (1971).

- ^ https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wess/wess_archive/1967wes_part2.pdf World Economic Survey, United Nations, 1967, Table 8 on page 14 (page 23 in the pdf file)

- ^ Markus A. Denzel, Handbook of World Exchange Rates, 1590-1914, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315253664/handbook-world-exchange-rates-1590%E2%80%931914-markus-denzel The piastre of 1839 contained 1.146 grammes of fine silver, the piastre of 1801 approximately 4.6 grammes of fine silver. The most important Egyptian coins, the bedidlik in gold (= 100 piastres; 7.487 grammes of fine gold) and the rial in silver (20 piastres; 23.294 grammes of fine silver)

- ^ Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2009). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money Specialized Issues (11 ed.). Krause. p. 1070. ISBN 978-1-4402-0450-0.

- ^ Egyptian Expeditionary Force, The Palestine News, 7 March 1918, p2. Turkish coins but not Turkish notes were legal. In January, a resident of Jerusalem was sentenced to 3 months' hard labour for selling a French Napoleon for 92.5 piastres instead of the regulation 77.15 piastres.

- ^ Egyptian Expeditionary Force, A Guide-Book to Central Palestine, August 1918, p106.

- ^ Standard catalogue of World Coins, Krause, Mishler, and Bruce, 1995, 22nd edition, page 1385

- ^ Schuler, Kurt. "Libya". Tables of Modern Monetary Systems. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007.

- ^ Franz Pick-Rene Sedillot. "All The Monies of the World - A Chronicle of Currency Values" Pick Publishing Corporation, New York, page 452 (1971).

- ^ Bank of England - Overseas Sterling Balances 1963-73 https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/1974/overseas-sterling-balances-1963-1973.pdf

![£E50 promissory note issued and hand-signed by Gen. Gordon during the Siege of Khartoum (26 April 1884)[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0c/SUD-S111b-Siege_of_Khartoum-50_Egyptian_Pounds_%281884%29.jpg/228px-SUD-S111b-Siege_of_Khartoum-50_Egyptian_Pounds_%281884%29.jpg)