Champagne Riots

The Champagne Riots of 1910 and 1911 resulted from a series of problems faced by grape growers in the Champagne area of France. These included four years of disastrous crop losses, the infestation of the phylloxera louse (which destroyed 15,000 acres (6,100 ha) of vineyards that year alone), low income and the belief that wine merchants were using grapes from outside the Champagne region. The precipitating event may have been the announcement in 1908 by the French government that it would delimit by decree the exact geographic area that would be granted economic advantage and protection by being awarded the Champagne appellation. This early development of Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée regulation benefitted the Marne and Aisne districts to the significant exclusion of the Aube district which included the town of Troyes—the historic capital of the Champagne region.[1]

Relationship between growers and Champagne houses

[edit]In the Champagne region, the production of Champagne is largely in the hands of producers who purchase grapes from independent growers. While some growers today produce wines under their own labels (known collectively as "grower Champagne"),[2] in the early 20th century the immense amount of capital needed to produce Champagne was beyond the reach of most growers. Champagne houses were able to bear the large risk of losing a considerable amount of product from exploding bottles as well as the cost of maintaining storage facilities for the long, labor-intensive process of making Champagne. This dynamic created a system that favored the Champagne houses as the only source of revenue for the vineyard owners. If the Champagne houses did not buy their grapes, a grower had little recourse or opportunity for another stream of income.[3]

Early discontent

[edit]

The discontent that eventually led to the riots began during the 19th century. The early vintages of the 20th century were difficult, due to frost and rains severely reducing the crop yields. The phylloxera epidemic that ravaged vineyards across France began to affect Champagne. The harvests between 1902 and 1909 were further troubled by mold and mildew. The 1910 vintages were afflicted by hailstorms and flooding. Nearly 96% of the crop was lost.[citation needed] Champagne's growing popularity, as well as the lack of grape supply in Champagne, encouraged the Champagne houses to look outside the Champagne region for a cheaper supply of grapes.[4] Some producers began using grapes from Germany and Spain.[3] The French railway system made it easy for large quantities of grapes from the Loire Valley or Languedoc to be transported to Champagne at prices nearly half of what the houses were paying Champenois vine growers for their grapes. Newspapers published rumors of some houses buying rhubarb from England to make wine from. With few laws in place to protect the vine grower or the consumer, Champagne houses held most of the power in the region to profit from these fake Champagnes. The Champenois vine growers were incensed at these practices, believing that using "foreign" grapes to make sparkling wine was not producing true Champagne. They petitioned the government for assistance and a law was passed requiring that at least 51% of the grapes used to make Champagne needed to come from the Champagne region itself.[4]

Collusion was practised among various Champagne houses in order to drive down the prices of grapes to as a low as they would go, with the ever-present threat that if the houses could not get their grapes cheaply enough they will continue to source grapes from outside the region. With vineyard owners vastly outnumbering the producers, the Champagne houses used this dynamic of excess supply vs limited demand to their advantage. They hired operatives, known as commissionaires, to negotiate prices with vine growers. These commissionaires were paid according to how low a price they could negotiate, so many used tactics including violence and intimidation. Some commissionaires openly sought bribes, often in the form of extra grapes, from vine growers to which they would sell themselves for profit. The prices they were able to negotiate rarely covered the cost of farming and harvesting which left many Champenois vine growers in poverty. Champenois vineyard owners were being paid less for fewer grapes. Poverty was widespread.[4]

Riots

[edit]

In January 1911, frustrations reached boiling point as riots erupted along the towns of Damery and Hautvilliers. Champenois vine growers intercepted trucks with grapes from the Loire Valley and pushed them into the Marne river. They then descended upon the warehouses of producers known to produce fake Champagne, tossing more wine and barrels into the Marne. The owner of Achille Perrier found his house surrounded by an angry mob chanting "A bas les fraudeurs" (Down with cheats). He was able to escape harm by hiding in the home of his concierge. The height of the violence was experienced in the village of Aÿ, located 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of Épernay.[4] [5][6] As the mob descended upon the city little was spared. Homes of private citizens as well as Champagne house producers were pillaged and ransacked. Somewhere a fire was started that spread throughout the city. The regional governor sent an urgent telegraph to Paris requesting assistance stating, "We are in a state of civil war!" By sunrise the entire village of Aÿ was burning.[4] To quell the violence, the French government sent over 40,000 troops to the region—setting up a billet in every village.[3]

Establishing the Champagne zone

[edit]

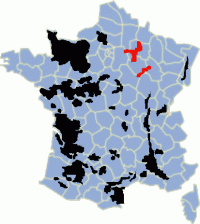

The relationship between the growers and Champagne producers was not the only source of tension. Within the Champagne region itself there was civil discontent among neighbors as to what truly represented "Champagne". The French Government tried to answer the vine growers concerns by passing legislation defining where Champagne wine was to come from. This early legislation dictated that the Marne department and a few villages from the Aisne department were the only areas approved to grow grapes for Champagne production. The glaring exclusion of the Aube region, where Troyes, the historic capital of Champagne, is located, promoted further discontent as the Aubois protested the decision. The Aube, located south of the Marne, was closer to the Burgundy region in terms of soil and location. The growers of the Marne viewed the region as "foreign" and not capable of producing true Champagne but the Aubois viewed themselves as Champenois and clung to their historical roots.[4]

Protest erupted from growers in the Aube district as they sought to be reinstated as part of the Champagne region. The government, trying to avoid any further violence and disruption, sought a "compromise solution" by designating the department as a second zone within the Champagne appellation. This provoked the growers in the Marne region to react violently to their loss of privilege and they lashed out again against merchants and producers who they accused of making wine from "foreign grapes"—including those from the Aube. Thousands of wine growers burned vineyards, destroyed the cellars of wine merchants, and ransacked houses as hundreds of liters of wine were lost.[7] The government was once again going back to the drawing-board in search of a solution to end the violence and appease all parties. Negotiations among vine growers, producers and government officials was ongoing when World War I broke out and the region saw all parties united in defense of country and the Champagne region.[4]

Aftermath

[edit]Following the riots, the French government worked with a collaboration of vineyard owners and Champagne houses to delineate an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée for the Champagne region. Only wines produced from grapes grown within the geographical boundaries (that included the Marne, Aube and parts of the Aisne departments) could be entitled to the name Champagne. Eventually these principles were enshrined by the European Union with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) status. To deal with the problem of collusion among Champagne houses and fairness in pricing, a classification system of Champagne's villages set up a price structure for the grapes.[8] Villages were rated on a numerical 80-100 scale based on the potential quality (and value) of their grapes. The price for a kilogram of grapes was set and vineyards owners would receive a fraction of that price depending on the village rating where they were located. Vineyards in Grand crus villages would receive 100% of the price while Premier crus village with a 95 rating would receive 95% of the price and so forth down the line. Today the business dynamic between Champagne houses and vineyards owners is not so strictly regulated but the classification system still serves as an aid in determining prices with Grand and Premier crus vineyards receiving considerably more for their grapes than vineyards in villages with ratings below 90%.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ R. Phillips A Short History of Wine pg 292 Harper Collins 2000 ISBN 0-06-621282-0

- ^ T. Stevenson, ed. The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia (4th Edition) pg 170-172 Dorling Kindersley 2005 ISBN 0-7513-3740-4

- ^ a b c H. Johnson Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 338-341, 440 Simon and Schuster 1989 ISBN 0-671-68702-6

- ^ a b c d e f g D. & P. Kladstrup Champagne pp 129-151 Harper Collins Publisher ISBN 0-06-073792-1

- ^ The history of Aÿ has been intimately connected with the pride and prestige of the Champagne region. In the 16th century, King Francis I was fond of calling himself the "Roi d' Aÿ et de Gonesse"—King of the lands where the country's greatest wines and flour were produced. Such was the reputation of the wines of Aÿ that they were known as the vins de France, their quality representing the whole of the country rather than just a region. Eventually the name of Aÿ became a shorthand term to refer to all the wines of the Champagne region. (Much like Bordeaux or Beaune is used today to refer to the wines of the Gironde and Burgundy regions, respectively).

- ^ H. Johnson Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 210-219 Simon and Schuster 1989 ISBN 0-671-68702-6

- ^ R. Phillips A Short History of Wine pg 293 Harper Collins 2000 ISBN 0-06-621282-0

- ^ J. Robinson (ed) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition pg 152-153 Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ^ K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 175 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-56305-434-5

External links

[edit] Media related to Revolt of the winegrovers of Champagne in 1911 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Revolt of the winegrovers of Champagne in 1911 at Wikimedia Commons- The New York Times archives "MORE CHAMPAGNE RIOTS.; Mob Sacks Wine Merchants' Houses In Disturbed District." (April 16, 1911)