Science and technology in Iran

Iran has made considerable advances in science and technology through education and training, despite international sanctions in almost all aspects of research during the past 30 years. Iran's university population swelled from 100,000 in 1979 to 4.7 million in 2016.[2] In recent years, the growth in Iran's scientific output is reported to be the fastest in the world.[3][4][5]

Science in ancient and Medieval Iran (Persia)

Science in Persia evolved in two main phases separated by the arrival and widespread adoption of Islam in the region.

References to scientific subjects such as natural science and mathematics occur in books written in the Pahlavi languages.

Ancient technology in Iran

The Qanat (a water management system used for irrigation) originated in pre-Achaemenid Iran. The oldest and largest known qanat is in the Iranian city of Gonabad, which, after 2,700 years, still provides drinking and agricultural water to nearly 40,000 people.[6]

Iranian philosophers and inventors may have created the first batteries (sometimes known as the Baghdad Battery) in the Parthian or Sasanian eras. Some have suggested that the batteries may have been used medicinally. Other scientists believe the batteries were used for electroplating—transferring a thin layer of metal to another metal surface—a technique still used today and the focus of a common classroom experiment.[7] However, due to the absence of electrodes on the exterior of the pot, and the lack of records of electroplating at the time, most archaeologists believe it is not a battery, and is more likely a ritual or storage object.[8][9]

Windwheels were developed by the Babylonians c. 1700 BC to pump water for irrigation. The horizontal or panemone windmill first appeared in Greater Iran during the 9th century.[10][11]

Mathematics

The first five rows of Khayam-Pascal's triangle

The 9th century mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi founded algebra and expanded upon Persian and Indian arithmetic systems. His writings were translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona under the title: De jebra et almucabola. Robert of Chester also translated it under the title Liber algebras et almucabala. The works of Kharazmi "exercised a profound influence on the development of mathematical thought in the medieval West".[12]

The Banū Mūsā brothers ("Sons of Moses"), namely Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873), Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century) and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century), were three 9th-century Persian[13][14] scholars who lived and worked in Baghdad. They are known for their Book of Ingenious Devices on automata and mechanical devices and their Book on the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures.[15]

Other Iranian scientists included Abu Abbas Fazl Hatam, Farahani, Omar Ibn Farakhan, Abu Zeid Ahmad Ibn Soheil Balkhi (9th century AD), Abul Vafa Bouzjani, Abu Jaafar Khan, Bijan Ibn Rostam Kouhi, Ahmad Ibn Abdul Jalil Qomi, Bu Nasr Araghi, Abu Reyhan Birooni, the noted Iranian poet Hakim Omar Khayyam Neishaburi, Qatan Marvazi, Massoudi Ghaznavi (13th century AD), Khajeh Nassireddin Tusi, and Ghiasseddin Jamshidi Kashani.

Medicine

The hospital system was developed in Sassanian Iran; for example, the Academy of Gundishapur was influential on the ideals and traditions of hospitals in the Mohammedan period.[16]

Several documents still exist from which the definitions and treatments of the headache in medieval Persia can be ascertained. These documents give detailed and precise clinical information on the different types of headaches. The medieval physicians listed various signs and symptoms, apparent causes, and hygienic and dietary rules for prevention of headaches. The medieval writings are both accurate and vivid, and they provide long lists of substances used in the treatment of headaches. Many of the approaches of physicians in medieval Persia are accepted today; however, still more of them could be of use to modern medicine.[17]

During the 7th century the Achaemenian dynasty was the major advocate of science. Documents indicate that condemned criminals' bodies were dissected and used for medical research during this timeframe[18] In due course, Persians' methods of gathering scientific information would undergo a major change. In the aftermath of the conquest of Islam, Muslim armies destroyed major libraries, and as a result, Persian scholars were deeply concerned as knowledge of the fields of science had been lost. Persians also prohibited the use of human anatomical dissection by Muslim medical practitioners for social and religious reasons.[18] Persian literature was translated into Arabic for approximately two centuries to preserve the surviving Persians literature, which also indirectly served to conserve Persian history.[18]

In the 10th century work of Shahnameh, Ferdowsi describes a Caesarean section performed on Rudabeh, during which a special wine agent was prepared by a Zoroastrian priest and used to produce unconsciousness for the operation.[19] Although largely mythical in content, the passage illustrates working knowledge of anesthesia in ancient Persia.

Later in the 10th century, Abu Bakr Muhammad Bin Zakaria Razi is considered the founder of practical physics and the inventor of the special or net weight of matter. His student, Abu Bakr Joveini, wrote the first comprehensive medical book in the Persian language.

After the Islamic conquest of Iran, medicine continued to flourish with the rise of notables such as Rhazes and Haly Abbas, albeit Baghdad was the new cosmopolitan inheritor of Sassanid Jundishapur's medical academy. Rhaze noted that different diseases might have similar signs and symptoms, which highlights Rhazes' contribution to applied neuroanatomy. The differential diagnosis approach is still used in modern medicine. His music therapy was used as a means of promoting healing and he was one of the first people to realize that diet influences the function of the body and the predisposition to disease[18]

An idea of the number of medical works composed in Persian alone may be gathered from Adolf Fonahn's Zur Quellenkunde der Persischen Medizin, published in Leipzig in 1910. The author enumerates over 400 works in the Persian language on medicine, excluding authors such as Avicenna, who wrote in Arabic. Author-historians Meyerhof, Casey Wood, and Hirschberg also have recorded the names of at least 80 oculists who contributed treatises on subjects related to ophthalmology from the beginning of 800 AD to the full flowering of Muslim medical literature in 1300 AD.

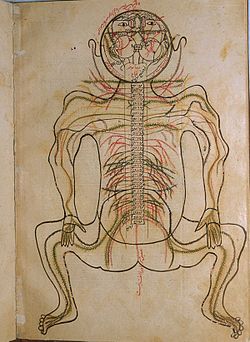

Aside from the aforementioned, two other medical works attracted great attention in medieval Europe, namely Abu Mansur Muwaffaq's Materia Medica, written around 950 AD, and the illustrated Anatomy of Mansur ibn Muhammad, written in 1396 AD.

Modern academic medicine began in Iran when Joseph Cochran established a medical college in Urmia in 1878. Cochran is often credited for founding Iran's "first contemporary medical college".[20] The website of Urmia University credits Cochran for "lowering the infant mortality rate in the region"[21] and for founding one of Iran's first modern hospitals (Westminster Hospital) in Urmia.

Iran started contributing to modern medical research late in 20th century. Most publications were from pharmacology and pharmacy labs located at a few top universities, most notably Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Ahmad Reza Dehpour and Abbas Shafiee were among the most prolific scientists in that era. Research programs in immunology, parasitology, pathology, medical genetics, and public health were also established in late 20th century. In 21st century, we witnessed a huge surge in the number of publications in medical journals by Iranian scientists on nearly all areas in basic and clinical medicine. Interdisciplinary research were introduced during 2000s and dual degree programs including Medicine/Science, Medicine/Engineering and Medicine/Public health programs were founded. Alireza Mashaghi was one of the main figures behind the development of interdisciplinary research and education in Iran.[citation needed]

Astronomy

In 1000 AD, Biruni wrote an astronomical encyclopaedia that discussed the possibility that the earth might revolve around the sun. This was before Tycho Brahe drew the first maps of the sky, using stylized animals to depict the constellations.

In the tenth century, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi recorded the first known reference to the Andromeda galaxy, which he called a "little cloud".[22]

In 830, the Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi wrote the first major work of Muslim astronomy. In addition to presenting tables covering the movements of the Sun, Moon and the five planets, Ptolemaic concepts were introduced into Islamic science through this work.[23]

Biology

Abu Hanifa Dinawari is considered the founder of Arabic botany for his Kitab al-Nabat (Book of Plants), which consisted of six volumes. Only the third and fifth volumes have survived, though the sixth volume has partly been reconstructed based on citations from later works. In the surviving portions of his works, 637 plants are described from the letters sin to ya. He describes the phases of plant growth and the production of flowers and fruit.[24]

Medieval Islamic agronomists including Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr described agricultural and horticultural techniques including how to propagate the olive and the date palm, crop rotation of flax with wheat or barley, and companion planting of grape and olive.[25]

Chemistry

The authors of the alchemical texts (c. 850−950) attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan pioneered the chemical use of vegetable and animal substances, which at the time represented an innovative shift towards organic chemistry.[26] One of the innovations in Jabirian alchemy was the addition of sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride) to the category of chemical substances known as 'spirits' (i.e., strongly volatile substances). This included both naturally occurring sal ammoniac and synthetic ammonium chloride as produced from organic substances, and so the addition of sal ammoniac to the list of 'spirits' is likely a product of the new focus on organic chemistry. Since the word for sal ammoniac used in the Jabirian corpus (nūshādhir) is Iranian in origin, it has been suggested that the direct precursors of Jabirian alchemy may have been active in the Hellenizing and Syriacizing schools of the Sasanian Empire.[27]

The Persian alchemist and physician Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 865–925) conducted experiments with the heating of sal ammoniac, vitriol, and other salts, which would eventually lead to the discovery of mineral acids by thirteenth century Latin alchemists such as pseudo-Geber.[28]

Physics

Kamal al-Din Al-Farisi (1267–1318) born in Tabriz, Iran, is known for giving the first mathematically satisfactory (though incorrect) explanation of the rainbow, and an explication of the nature of colours that reformed the theory of Ibn al-Haytham. Al-Farisi also "proposed a model where the ray of light from the sun was refracted twice by a water droplet, one or more reflections occurring between the two refractions."[citation needed] He tested this through experimentation using a transparent sphere filled with water.

Science policy

The Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology and the National Research Institute for Science Policy come under the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology. They are in charge of establishing national research policies.

The government first set its sights on moving from a resource-based economy to one based on knowledge in its 20-year development plan, Vision 2025, adopted in 2005. This transition became a priority after international sanctions were progressively hardened from 2006 onwards and the oil embargo tightened its grip. In February 2014, the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei introduced what he called the 'economy of resistance', an economic plan advocating innovation and a lesser dependence on imports that reasserted key provisions of Vision 2025.[29]

Vision 2025 challenged policy-makers to look beyond extractive industries to the country's human capital for wealth creation. This led to the adoption of incentive measures to raise the number of university students and academics, on the one hand, and to stimulate problem-solving and industrial research, on the other.[29]

Iran's successive five-year plans aim to realize collectively the goals of Vision 2025. For instance, in order to ensure that 50% of academic research was oriented towards socio-economic needs and problem-solving, the Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015) tied promotion to the orientation of research projects. It also made provision for research and technology centres to be set up on campus and for universities to develop linkages with industry. The Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan had two main thrusts relative to science policy. The first was the "islamization of universities', a notion that is open to broad interpretation. According to Article 15 of the Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan, university programmes in the humanities were to teach the virtues of critical thinking, theorization and multidisciplinary studies. A number of research centres were also to be developed in the humanities. The plan's second thrust was to make Iran the second-biggest player in science and technology by 2015, behind Turkey. To this end, the government pledged to raise domestic research spending to 3% of GDP by 2015.[29] Yet, R&D's share in the GNP is at 0.06% in 2015 (where it should be at least 2.5% of GDP)[30][31] and industry-driven R&D is almost non‑existent.[32]

Vision 2025 fixed a number of targets, including that of raising domestic expenditure on research and development to 4% of GDP by 2025. In 2012, spending stood at 0.33% of GDP.[29]

In 2009, the government adopted a National Master Plan for Science and Education to 2025 which reiterates the goals of Vision 2025. It lays particular stress on developing university research and fostering university–industry ties to promote the commercialization of research results.[29][33][34][35][36][37]

In early 2018, the Science and Technology Department of the Iranian President's Office released a book to review Iran's achievements in various fields of science and technology during 2017. The book, entitled "Science and Technology in Iran: A Brief Review", provides the readers with an overview of the country's 2017 achievements in 13 different fields of science and technology.[38]

Human resources

In line with the goals of Vision 2025, policy-makers have made a concerted effort to increase the number of students and academic researchers. To this end, the government raised its commitment to higher education to 1% of GDP in 2006. After peaking at this level, higher education spending stood at 0.86% of GDP in 2015. Higher education spending has resisted better than public expenditure on education overall. The latter peaked at 4.7% of GDP in 2007 before slipping to 2.9% of GDP in 2015. Vision 2025 fixed a target of raising public expenditure on education to 7% of GDP by 2025.[29]

Student enrollment trends

The result of greater spending on higher education has been a steep rise in tertiary enrollment. Between 2007 and 2013, student rolls swelled from 2.8 million to 4.4 million in the country's public and private universities. Some 45% of students were enrolled in private universities in 2011. There were more women studying than men in 2007, a proportion that has since dropped back slightly to 48%.[29]

Enrollment has progressed in most fields. The most popular in 2013 were social sciences (1.9 million students, of which 1.1 million women) and engineering (1.5 million, of which 373 415 women). Women also made up two-thirds of medical students. One in eight bachelor's students go on to enroll in a master's/PhD programme. This is comparable to the ratio in the Republic of Korea and Thailand (one in seven) and Japan (one in ten).[29]

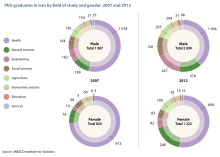

The number of PhD graduates has progressed at a similar pace as university enrollment overall. Natural sciences and engineering have proved increasingly popular among both sexes, even if engineering remains a male-dominated field. In 2012, women made up one-third of PhD graduates, being drawn primarily to health (40% of PhD students), natural sciences (39%), agriculture (33%) and humanities and arts (31%). According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 38% of master's and PhD students were studying science and engineering fields in 2011.[29]

There has been an interesting evolution in the gender balance among PhD students. Whereas the share of female PhD graduates in health remained stable at 38–39% between 2007 and 2012, it rose in all three other broad fields. Most spectacular was the leap in female PhD graduates in agricultural sciences from 4% to 33% but there was also a marked progression in science (from 28% to 39%) and engineering (from 8% to 16% of PhD students). Although data are not readily available on the number of PhD graduates choosing to stay on as faculty, the relatively modest level of domestic research spending would suggest that academic research suffers from inadequate funding.[29]

The Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015) fixed the target of attracting 25 000 foreign students to Iran by 2015. By 2013, there were about 14 000 foreign students attending Iranian universities, most of whom came from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria and Turkey. In a speech delivered at the University of Tehran in October 2014, President Rouhani recommended greater interaction with the outside world. He said that

scientific evolution will be achieved by criticism [...] and the expression of different ideas. [...] Scientific progress is achieved, if we are related to the world. [...] We have to have a relationship with the world, not only in foreign policy but also with regard to the economy, science and technology. [...] I think it is necessary to invite foreign professors to come to Iran and our professors to go abroad and even to create an English university to be able to attract foreign students.'[29]

One in four Iranian PhD students were studying abroad in 2012 (25.7%). The top destinations were Malaysia, the US, Canada, Australia, UK, France, Sweden and Italy. In 2012, one in seven international students in Malaysia was of Iranian origin. There is a lot of scope for the development of twinning between universities for teaching and research, as well as for student exchanges.[29]

Trends in researchers

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the number of (full-time equivalent) researchers rose from 711 to 736 per million inhabitants between 2009 and 2010. This corresponds to an increase of more than 2 000 researchers, from 52 256 to 54 813. The world average is 1 083 per million inhabitants. One in four (26%) Iranian researchers is a woman, which is close to the world average (28%). In 2008, half of researchers were employed in academia (51.5%), one-third in the government sector (33.6%) and just under one in seven in the business sector (15.0%). Within the business sector, 22% of researchers were women in 2013, the same proportion as in Ireland, Israel, Italy and Norway. The number of firms declaring research activities more than doubled between 2006 and 2011, from 30 935 to 64 642. The increasingly tough sanctions regime oriented the Iranian economy towards the domestic market and, by erecting barriers to foreign imports, encouraged knowledge-based enterprises to localize production.[29]

Research expenditure

Iran's national science budget was about $900 million in 2005 and it had not been subject to any significant increase for the previous 15 years.[39] In 2001, Iran devoted 0.50% of GDP to research and development. Expenditure peaked at 0.67% of GDP in 2008 before receding to 0.33% of GDP in 2012, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.[40] The world average in 2013 was 1.7% of GDP. Iran's government has devoted much of its budget to research on high technologies such as nanotechnology, biotechnology, stem cell research and information technology (2008).[41] In 2006, the Iranian government wiped out the financial debts of all universities in a bid to relieve their budget constraints.[42] According to the UNESCO science report 2010, most research in Iran is government-funded with the Iranian government providing almost 75% of all research funding.[43] Domestic expenditure on research stood at 0.7% of GDP in 2008 and 0.3% of GDP in 2012. Iranian businesses contributed about 11% of the total in 2008. The government's limited budget is being directed towards supporting small innovative businesses, business incubators and science and technology parks, the type of enterprises which employ university graduates.[29]

The share of private businesses in total national R&D funding according to the same report is very low, being just 14%, as compared with Turkey's 48%. The rest of approximately 11% of funding comes from higher education sector and non-profit organizations.[44] A limited number of large enterprises (such as IDRO, NIOC, NIPC, DIO, Iran Aviation Industries Organization, Iranian Space Agency, Iran Electronics Industries or Iran Khodro) have their own in-house R&D capabilities.[45]

Funding the transition to a knowledge economy

Vision 2025 foresaw an investment of US$3.7 trillion by 2025 to finance the transition to a knowledge economy. It was intended for one-third of this amount to come from abroad but, so far, FDI has remained elusive. It has contributed less than 1% of GDP since 2006 and just 0.5% of GDP in 2014. Within the country's Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015), a National Development Fund has been established to finance efforts to diversify the economy. By 2013, the fund was receiving 26% of oil and gas revenue.[29]

Much of the US$3.7 trillion earmarked in Vision 2025 is to go towards supporting investment in research and development by knowledge-based firms and the commercialization of research results. A law passed in 2010 provides an appropriate mechanism, the Innovation and Prosperity Fund. According to the fund's president, Behzad Soltani, 4600 billion Iranian rials (circa US$171.4 million) had been allocated to 100 knowledge-based companies by late 2014. Public and private universities wishing to set up private firms may also apply to the fund.[29]

Some 37 industries trade shares on the Tehran Stock Exchange. These industries include the petrochemical, automotive, mining, steel, iron, copper, agriculture and telecommunications industries, 'a unique situation in the Middle East'. Most of the companies developing high technologies remain state-owned, including in the automotive and pharmaceutical industries, despite plans to privatize 80% of state-owned companies by 2014. It was estimated in 2014 that the private sector accounted for about 30% of the Iranian pharmaceutical market.[29]

The Industrial Development and Renovation Organization (IDRO) controls about 290 state-owned companies. IDRO has set up special purpose companies in each high-tech sector to coordinate investment and business development. These entities are the Life Science Development Company, Information Technology Development Centre, Iran InfoTech Development Company and the Emad Semiconductor Company. In 2010, IDRO set up a capital fund to finance the intermediary stages of product- and technology-based business development within these companies.[29]

Technology parks

As of 2012, Iran had officially 31 science and technology parks nationwide.[citation needed] Furthermore, as of 2014, 36 science and technology parks hosting more than 3,650 companies were operating in Iran.[46] These firms have directly employed more than 24,000 people.[46] According to the Iran Entrepreneurship Association, there are ninety-nine (99) parks of science and technology, in totality, which operate without official permits. Twenty-one of those parks are located in Tehran and affiliated with University Jihad, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran University, Ministry of Energy (Iran), Ministry of Health and Medical Education, and Amir Kabir University among others. Fars Province, with 8 parks and Razavi Khorasan Province, with 7 parks, are ranked second and third after Tehran respectively.[47]

| Park's name | Focus area | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Guilan Science and Technology Park | Agro-Food, Biotechnology, Chemistry, Electronics, Environment, ICT, Tourism.[48] | Guilan |

| Pardis Technology Park | Advanced Engineering (mechanics and automation), Biotechnology, Chemistry, Electronics, ICT, Nano-technology.[48] | 25 km North-East of Tehran |

| Tehran Software and Information Technology Park (planned)[49] | ICT[50] | Tehran |

| Tehran University and Science Technology Park[51] | Tehran | |

| Khorasan Science and Technology Park (Ministry of Science, Research and Technology) | Advanced Engineering, Agro-Food, Chemistry, Electronics, ICT, Services.[48] | Khorasan |

| Sheikh Bahai Technology Park (Aka "Isfahan Science and Technology Town") | Materials and Metallurgy, Information and Communications Technology, Design & Manufacturing, Automation, Biotechnology, Services.[48] | Isfahan |

| Semnan Province Technology Park | Semnan | |

| East Azerbaijan Province Technology Park | East Azerbaijan | |

| Yazd Province Technology Park | Yazd | |

| Mazandaran Science and Technology Park | Mazandaran | |

| Markazi Province Technology Park | Arak | |

| "Kahkeshan" (Galaxy) Technology Park[citation needed] | Aerospace | Tehran |

| Pars Aero Technology Park[52] | Aerospace & Aviation | Tehran |

| Energy Technology Park (planned)[53] | Energy | — |

Innovation

As of 2004, Iran's national innovation system (NIS) had not experienced a serious entrance to the technology creation phase and mainly exploited the technologies developed by other countries (e.g. in the petrochemicals industry).[54]

In 2016, Iran ranked second in the percentage of graduates in science and engineering in the Global Innovation Index. Iran also ranked fourth in tertiary education, 26 in knowledge creation, 31 in gross percentage of tertiary enrollment, 41 in general infrastructure, 48 in human capital as well as research and 51 in innovation efficiency ratio.[55]

In recent years several drugmakers in Iran are gradually developing the ability to innovate, away from generic drugs production itself.[56]

According to the State Registration Organization of Deeds and Properties, a total of 9,570 national inventions were registered in Iran during 2008. Compared with the previous year, there was a 38-percent increase in the number of inventions registered by the organization.[57] Iran was ranked 62nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, up from 67th in 2020.[58][59]

Iran has several funds to support entrepreneurship and innovation:[47]

- Innovation and Flourishing/Prosperity Fund of the Directorate of Science and Technology of the Presidential Office;

- National Researchers and Industrialists Support Fund;

- Nokhbegan Technology Development Institute;

- Nanotechnology Fund;

- Iran Biotech Fund;

- Novin Technology Development Fund;

- Sharif Export Development Research and Technology Fund;

- Support Fund of Researchers and Technologists;

- Payambar Azam (the great prophet) Scientific and Technological Award;

- Student Entrepreneurs Support Fund;

- +6,000 private interest-free funds & 3 venture capital funds (Shenasa, Simorgh and Sarava Pars). See also: Banking in Iran.

Private sector

The 5th Development Plan (2010–15) requires the private sector to communicate research needs to universities so that universities would coordinate research projects in line with these needs, with sharing of expenses by both sides.[53]

Because of its weakness or absence, the support industry makes little contribution to the innovation/technology development activities. Supporting the development of small and medium enterprises in Iran will strengthen greatly the supplier network.[45]

As of 2014, Iran had 930 industrial parks and zones, of which 731 are ready to be ceded to the private sector.[60] The government of Iran has plans for the establishment of 50–60 new industrial parks by the end of the fifth Five-Year Socioeconomic Development Plan (2015).[61]

As of 2016, Iran had nearly 3,000 knowledge-based companies.[62] As of February 2023, this number increased to 8,046. The number of knowledge-based companies in biotechnology, agriculture, and food industries is 362, in advanced pharmaceuticals is 480, in advanced materials (chemistry and polymer) is 1130, and in advanced machinery and equipment is 1721. This number is 326 companies in the field of medical equipment, 1821 in electricity and electronics, 1778 in information technology, 397 in commercialization, and 31 companies in creative industries and humanities.[63]

A 2003-report by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization regarding small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)[64] identified the following impediments to industrial development:

- Lack of monitoring institutions;

- Inefficient banking system;

- Insufficient research & development;

- Shortage of managerial skills;

- Corruption;

- Inefficient taxation;

- Socio-cultural apprehensions;

- Absence of social learning loops;

- Shortcomings in international market awareness necessary for global competition;

- Cumbersome bureaucratic procedures;

- Shortage of skilled labor;

- Lack of intellectual property protection;

- Inadequate social capital, social responsibility and socio-cultural values.

The economic complexity ranking of Iran has increased by 1 places over the past 50 years from 66th in 1964 to 65th in 2014.[65] According to UNCTAD in 2016, private companies in Iran need better marketing strategies with emphasis on innovation.[62]

Despite these problems, Iran has progressed in various scientific and technological fields, including petrochemical, pharmaceutical, aerospace, defense, and heavy industry. Even in the face of economic sanctions, Iran is emerging as an industrialized country.[66]

Parallel to academic research, several companies have been founded in Iran during last few decades. For example, CinnaGen, established in 1992, is one of the pioneering biotechnology companies in the region. CinnaGen won Biotechnology Asia 2005 Innovation Awards due to its achievements and innovation in biotechnology research. In 2006, Parsé Semiconductor Co. announced it had designed and produced a 32-bit computer microprocessor inside the country for the first time.[67] Software companies are growing rapidly. In CeBIT 2006, ten Iranian software companies introduced their products.[68][69]

In FY 2019, around 5,000 Iranian knowledge-based companies sold $28 billion worth of products or services including pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, polymer and chemical products, and industrial machinery. Among them, 250 companies exported $400 million to Central Asia and all of Iran's direct neighbours.[70]

Science in modern Iran

Theoretical and computational sciences are highly developed in Iran.[71] Despite the limitations in funds, facilities, and international collaborations, Iranian scientists have been very productive in several experimental fields such as pharmacology, pharmaceutical chemistry, and organic and polymer chemistry. Iranian biophysicists, especially molecular biophysicists, have gained international reputations since the 1990s[citation needed]. High field nuclear magnetic resonance facility, microcalorimetry, circular dichroism, and instruments for single protein channel studies have been provided in Iran during the past two decades. Tissue engineering and research on biomaterials have just started to emerge in biophysics departments.

Considering the country's brain drain and its poor political relationship with the United States and some other Western countries, Iran's scientific community remains productive, even while economic sanctions make it difficult for universities to buy equipment or to send people to the United States to attend scientific meetings.[72] Furthermore, Iran considers scientific backwardness, as one of the root causes of political and military bullying by developed countries over developing states.[73] After the Iranian Revolution, there have been efforts by the religious scholars to assimilate Islam with modern science and this is seen by some as the reason behind the recent successes of Iran to augment its scientific output.[74] Currently Iran aims for a national goal of self-sustainment in all scientific arenas.[75][76] Many individual Iranian scientists, along with the Iranian Academy of Medical Sciences and Academy of Sciences of Iran, are involved in this revival. The Comprehensive Scientific Plan has been devised based on about 51,000 pages of documents and includes 224 scientific projects that must be implemented by the year 2025.[77][78]

Medical sciences

With over 400 medical research facilities and 76 medical magazine indexes available in the country, Iran is the 19th country in medical research and is set to become the 10th within 10 years (2012).[citation needed] Clinical sciences are invested in highly in Iran. In areas such as rheumatology, hematology, and bone marrow transplantation, Iranian medical scientists publish regularly.[79] The Hematology, Oncology and Bone Marrow Transplantation Research Center (HORC) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Shariati Hospital was established in 1991. Internationally, this center is one of the largest bone marrow transplantation centers and has carried out a large number of successful transplantations.[80] According to a study conducted in 2005, associated specialized pediatric hematology and oncology (PHO) services exist in almost all major cities throughout the country, where 43 board-certified or eligible pediatric hematologist–oncologists are giving care to children suffering from cancer or hematological disorders. Three children's medical centers at universities have approved PHO fellowship programs.[81] Besides hematology, gastroenterology has recently attracted many talented medical students. The gasteroenterology research center based at Tehran University of Medical Sciences has produced increasing numbers of scientific publications since its establishment.

Modern organ transplantation in Iran dates to 1935, when the first cornea transplant in Iran was performed by Professor Mohammad-Qoli Shams at Farabi Eye Hospital in Tehran, Iran. The Shiraz Nemazi transplant center, also one of the pioneering transplant units of Iran, performed the first Iranian kidney transplant in 1967 and the first Iranian liver transplant in 1995. The first heart transplant in Iran was performed in 1993 in Tabriz. The first lung transplant was performed in 2001, and the first heart and lung transplants were performed in 2002, both at Tehran University of Medical Sciences.[82] Currently, renal, liver, and heart transplantations are routinely performed in Iran. Iran ranks fifth in the world in kidney transplants.[83] The Iranian Tissue Bank, commencing in 1994, was the first multi-facility tissue bank in country. In June 2000, the Organ Transplantation Brain Death Act was approved by the Parliament, followed by the establishment of the Iranian Network for Transplantation Organ Procurement. This act helped to expand heart, lung, and liver transplantation programs. By 2003, Iran had performed 131 liver, 77 heart, 7 lung, 211 bone marrow, 20,581 cornea, and 16,859 renal transplantations. 82 percent of these were donated by living and unrelated donors; 10 percent by cadavers; and 8 percent came from living-related donors. The 3-year renal transplant patient survival rate was 92.9%, and the 40-month graft survival rate was 85.9%.[82]

Neuroscience is also emerging in Iran.[84] A few PhD programs in cognitive and computational neuroscience have been established in the country during recent decades.[85] Iran ranks first in Mideast and region in ophthalmology.[86][87]

Iranian surgeons treating wounded Iranian veterans during the Iran–Iraq War invented a new neurosurgical treatment for brain injured patients that laid to rest the previously prevalent technique developed by United States Army surgeon Dr Ralph Munslow. This new surgical procedure helped devise new guidelines that have decreased death rates for comatosed patients with penetrating brain injuries from 55% of 1980 to 20% of 2010. It has been said that these new treatment guidelines benefited US congresswoman Gabby Giffords who had been shot in the head.[88][89][90]

Biotechnology

Planning and attention to biotechnology in Iran started in 1996 with the formation of the Supreme Council for Biotechnology. The Biotech National Document targeted to develop the technology in the country in 2004 was approved by the government.

In 1999, with the aim of developing and synergies, particularly with regard to the importance of new technologies and strategic location of biotechnology, the Biotechnology Development Council was established under the vice presidency of science and technology and all activities of the former Supreme Council were held at the headquarters. According to the Supreme Leader, emphasis on special attention to the development of biotechnology and biotech presenting to emphasize the development of a five-year program of economic, social and cultural, Biotech Development Council according to Act 705 dated 27 October 1390 Session Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution as The main reference of Policy, planning, strategy implementation, coordination and monitoring in the field of biotechnology was determined. Iran has a biotechnology sector that is one of the most advanced in the developing world.[91][92] The Razi Institute for Serums and Vaccines and the Pasteur Institute of Iran are leading regional facilities in the development and manufacture of vaccines. In January 1997, the Iranian Biotechnology Society (IBS) was created to oversee biotechnology research in Iran.[91]

Agricultural research has been successful in releasing high-yielding varieties with higher stability as well as tolerance to harsh weather conditions. The agriculture researchers are working jointly with international Institutes to find the best procedures and genotypes to overcome produce failure and to increase yield. In 2005, Iran's first genetically modified (GM) rice was approved by national authorities and is being grown commercially for human consumption. In addition to GM rice, Iran has produced several GM plants in the laboratory, such as insect-resistant maize; cotton; potatoes and sugar beets; herbicide-resistant canola; salinity- and drought-tolerant wheat; and blight-resistant maize and wheat.[93] The Royan Institute engineered Iran's first cloned animal; the sheep was born on 2 August 2006 and passed the critical first two months of his life.[94][95]

In the last months of 2006, Iranian biotechnologists announced that they, as the third manufacturer in the world, have sent CinnoVex (a recombinant type of Interferon b1a) to the market.[96] According to a study by David Morrison and Ali Khademhosseini (Harvard-MIT and Cambridge), stem cell research in Iran is amongst the top 10 in the world.[97] Iran planned to invest 2.5 billion dollars in the country's stem cell research in the years 2008–2013.[98] Iran ranks second in the world in transplantation of stem cells.[99]

According to Scopus, Iran ranked 21st in biotechnology by producing nearly 4,000 related-scientific articles in 2014.[100]

In 2010, AryoGen Biopharma established the biggest and most modern knowledge-based facility for production of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in the region. As at 2012, Iran produced 15 types of monoclonal/anti-body drugs. These anti-cancer drugs are now produced by only two to three western companies.[101]

In 2015, Noargen[102] company was established as the first officially registered CRO and CMO in Iran. Noargen uses the concept of CMO and CRO servicing to the biopharma sector of Iran as its main activity to fill the gap and promote developing biotech ideas/products toward commercialization.

Physics and materials

Iran had some significant successes in nuclear technology during recent decades, especially in nuclear medicine. However, little connection exists between Iran's scientific society and that of the nuclear program of Iran. Iran is the 7th country in production of uranium hexafluoride (or UF6).[103] Iran now controls the entire cycle for producing nuclear fuel.[104] Iran is among the 14 countries in possession of nuclear [energy] technology. In 2009, Iran was developing its first domestic Linear particle accelerator (LINAC).[105]

It is among the few countries in the world that has the technology to produce zirconium alloys.[106][107] Iran produces a wide range of lasers in demand within the country in medical and industrial fields.[citation needed] In 2018, Iran inaugurated the first laboratory for quantum entanglement in the National Laser Center.[108]

Computer science, electronics and robotics

The Center of Excellence in Design, Robotics, and Automation was established in 2001 to promote educational and research activities in the fields of design, robotics, and automation. Besides these professional groups, several robotics groups work in Iranian high schools.[109] "Sorena 2" Robot, which was designed by engineers at University of Tehran, was unveiled in 2010. The robot can be used for handling sensitive tasks without the need for cooperating with human beings. The robot is taking slow steps similar to human beings, harmonious movements of hands and feet and other movements similar to humans.[110][111][112] Next the researchers plan to develop speech and vision capabilities and greater intelligence for this robot.[113] the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has placed the name of Surena among the five prominent robots of the world after analyzing its performance.[114]

Ultra Fast Microprocessors Research Center in Tehran's Amirkabir University of Technology successfully built a supercomputer in 2007.[115] Maximum processing capacity of the supercomputer is 860 billion operations per second. Iran's first supercomputer launched in 2001 was also fabricated by Amirkabir University of Technology.[116] In 2009, a SUSE Linux-based HPC system made by the Aerospace Research Institute of Iran (ARI) was launched with 32 cores and now runs 96 cores. Its performance was pegged at 192 GFLOPS.[117] Iran's National Super Computer made by Iran Info-Tech Development Company (a subsidiary of IDRO) was built from 216 AMD processors. The Linux-cluster machine has a reported "theoretical peak performance of 860 gig-flops".[118] The Routerlab team at the University of Tehran successfully designed and implemented an access-router (RAHYAB-300) and a 40 Gbit/s high capacity switch fabric (UTS).[119] In 2011 Amirkabir University of Technology and Isfahan University of Technology produced 2 new supercomputers with processing capacity of 34,000 billion operations per second.[120] The supercomputer at Amirkabir University of Technology is expected to be among the 500 most powerful computers in the world.[120] From 1997 until 2017, Iran submitted 34,028 articles about Artificial Intelligence and its usage, ranking it at the 14th place in the world in the area of artificial intelligence (it is the 8th country in the world in AI based on high impact and high citation articles).[121]

Chemistry and nanotechnology

Iran is ranked 120th in the field of chemistry (2018).[122] In 2007, Iranian scientists at the Medical Sciences and Technology Center succeeded in mass-producing an advanced scanning microscope—the Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM).[123] By 2017, Iran ranked 4th in ISI indexed nano-articles.[124][125][126][127][128] Iran has designed and mass-produced more than 35 kinds of advanced nanotechnology devices. These include laboratory equipment, antibacterial strings, power station filters and construction related equipment and materials.[129]

Research in nanotechnology has taken off in Iran since the Nanotechnology Initiative Council (NIC) was founded in 2002. The council determines the general policies for the development of nanotechnology and co-ordinates their implementation. It provides facilities, creates markets and helps the private sector to develop relevant R&D activities. In the past decade, 143 nanotech companies have been established in eight industries. More than one-quarter of these are found in the health care industry, compared to just 3% in the automotive industry.[29]

Today, five research centres specialize in nanotechnology, including the Nanotechnology Research Centre at Sharif University, which established Iran's first doctoral programme in nanoscience and nanotechnology a decade ago. Iran also hosts the International Centre on Nanotechnology for Water Purification, established in collaboration with UNIDO in 2012. In 2008, NIC established an Econano network to promote the scientific and industrial development of nanotechnology among fellow members of the Economic Cooperation Organization, namely Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.[29]

Iran recorded strong growth in the number of articles on nanotechnology between 2009 and 2013, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science. By 2013, Iran ranked seventh for this indicator. The number of articles per million population has tripled to 59, overtaking Japan in the process. Few patents are being granted to Iranian inventors in nanotechnology, as yet, however. The ratio of nanotechnology patents to articles was 0.41 per 100 articles for Iran in 2015.[29]

Aviation and space

On 17 August 2008, The Iranian Space Agency proceeded with the second test launch of a three stages Safir SLV from a site south of Semnan in the northern part of the Dasht-e-Kavir desert. The Safir (Ambassador) satellite carrier successfully launched the Omid satellite into orbit in February 2009.[130][131] Iran is the 9th country to put a domestically built satellite into orbit since the Soviet Union launched the first in 1957.[132] Iran is among a handful of countries in the world capable of developing satellite-related technologies, including satellite navigation systems.[133] Iran is the 8th country capable of manufacturing jet engines.[134]

Iran produces the HESA Simourgh cargo plane (based on re-engineering of the Antonov-140 ), the Yasin training jet (an indigenous platform) and the HESA Kawsar two-seat fighter (based on re-engineering of the F-5).

Astronomy

The Iranian government has committed 150 billion rials (roughly 16 million US dollars)[135] for a telescope, an observatory, and a training program, all part of a plan to build up the country's astronomy base. Iran wants to collaborate internationally and become internationally competitive in astronomy, says the University of Michigan's Carl Akerlof, an adviser to the Iranian project. "For a government that is usually characterized as wary of foreigners, that's an important development".[136] In 2016, Iran unveiled its new optical telescope for observing celestial objects as part of APSCO. It will be used to understand and predict the physical location of natural and man-made objects in orbit around the Earth.[137]

In 2022, Iran's National 3.4-meter Telescope (INO) captured and recorded its first image of deep space.

In 2024, using the Iranian National Observatory Lens Array (INOLA), the first ever attempt at exploring the stellar halo of M33 Galaxy using ultra-deep broad-band imaging was conducted and reported.[138]

Energy

Iran is ranked 12th in the field of energy (2018).[139] Iran is among the four world countries that are capable of manufacturing advanced V94.2 gas turbines.[140] Iran is able to produce all the parts needed for its gas refineries[141] and is now the third country in the world to have developed Gas to liquids (GTL) technology.[142][143] Iran produces 70% of its industrial equipment domestically including various turbines, pumps, catalysts, refineries, oil tankers, oil rigs, offshore platforms and exploration instruments.[144][145][146][147][148] Iran is among the few countries that has reached the technology and "know-how" for drilling in the deep waters.[149] Iran's indigenously designed Darkhovin Nuclear Power Plant is scheduled to come online in 2016.[150]

Armaments

Iran possesses the technology to launch superfast anti-submarine rockets that can travel at the speed of 100 meters per second under water, making the country second only to Russia in possessing the technology.[151] Iran is among the few countries that possess the technological know-how of the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) fitted with scanning and reconnaissance systems.[152] Since 1992, it also has produced its own tanks, armored personnel carriers, sophisticated radars, guided missiles, a submarine, and fighter planes.[153]

Scientific collaboration

Iran annually hosts international science festivals. The International Kharazmi Festival in Basic Science and The Annual Razi Medical Sciences Research Festival promote original research in science, technology, and medicine in Iran. There is also an ongoing R&D collaboration between large state-owned companies and the universities in Iran.

Iranians welcome scientists from all over the world to Iran for a visit and participation in seminars or collaborations. Many Nobel laureates and influential scientists such as Bruce Alberts, F. Sherwood Rowland, Kurt Wüthrich, Stephen Hawking, and Pierre-Gilles de Gennes visited Iran after the Iranian revolution. Some universities also hosted American and European scientists as guest lecturers during recent decades.

Although sanctions have caused a shift in Iran's trading partners from West to East, scientific collaboration has remained largely oriented towards the West. Between 2008 and 2014, Iran's top partners for scientific collaboration were the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Germany, in that order. Iranian scientists co-authored almost twice as many articles with their counterparts in the US (6 377) as with their next-closest collaborators in Canada (3 433) and the UK (3 318).[29] Iranian and U.S. scientists have collaborated on a number of projects.[154]

Malaysia is Iran's fifth-closest collaborator in science and India ranks tenth, after Australia, France, Italy and Japan. One-quarter of Iranian articles had a foreign co-author in 2014, a stable proportion since 2002. Scientists have been encouraged to publish in international journals in recent years, a policy that is in line with Vision 2025.[29]

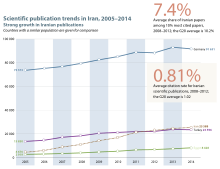

The volume of scientific articles authored by Iranians in international journals has augmented considerably since 2005, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). Iranian scientists now publish widely in international journals in engineering and chemistry, as well as in life sciences and physics. Women contribute about 13% of articles, with a focus on chemistry, medical sciences and social sciences. Contributing to this trend is the fact that PhD programmes in Iran now require students to have publications in the Web of Science.

Iran has submitted a formal request to participate in a project which is building an International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) in France by 2018. This megaproject is developing nuclear fusion technology to lay the groundwork for tomorrow's nuclear fusion power plants. The project involves the European Union, China, India, Japan, Republic of Korea, Russian Federation and United States. A team from ITER visited Iran in November 2016 to deepen its understanding of Iran's fusion-related programmes.[29][155]

Iran hosts several international research centres, including the following established between 2010 and 2014 under the auspices of the United Nations: the Regional Center for Science Park and Technology Incubator Development (UNESCO, est. 2010), the International Center on Nanotechnology (UNIDO, est. 2012) and the Regional Educational and Research Center for Oceanography for Western Asia (UNESCO, est. 2014).[29]

Iran is stepping up its scientific collaboration with developing countries. In 2008, Iran's Nanotechnology Initiative Council established an Econano network to promote the scientific and industrial development of nanotechnology among fellow members of the Economic Cooperation Organization, namely Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The Regional Centre for Science Park and Technology Incubator Development is also initially targeting these same countries. It is offering them policy advice on how to develop their own science parks and technology incubators.[29]

Iran is an active member of COMSTECH and collaborates on its international projects. The coordinator general of COMSTECH, Atta-ur-Rahman has said that Iran is the leader in science and technology among Muslim countries and hoped for greater cooperation with Iran in different international technological and industrialization projects.[156] Iranian scientists are also helping to construct the Compact Muon Solenoid, a detector for the Large Hadron Collider of the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) that is due to come online in 2008[citation needed]. Iranian engineers are involved in the design and construction of the first regional particle accelerator of the Middle East in Jordan, called SESAME.[157]

In 2024, Iran held talks with The Global South and Developing countries that were interested in scientific and technological cooperation with Iran in the field of peaceful nuclear science and technology,[158] which led to the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Burkina Faso in this field in September 2024.[159]

Since the lifting of international sanctions, Iran has been developing scientific and educational links with Kuwait, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, China and Russia.[160][161][162][163][164]

Contribution of Iranians and people of Iranian origin to modern science

Scientists with an Iranian background have made significant contributions to the international scientific community with Sunnis making up to 35% of the contributoons according to IranPolls.[165]

In 1960, Ali Javan invented first gas laser. In 1973, the fuzzy set theory was developed by Lotfi Zadeh. Iranian cardiologist Tofy Mussivand invented the first artificial heart and afterwards developed it further. HbA1c was discovered by Samuel Rahbar and introduced to the medical community. The Vafa-Witten theorem was proposed by Cumrun Vafa, an Iranian string theorist, and his co-worker Edward Witten. Nima Arkani-Hamed, is a noted theoretical physicist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton who is known for large extra dimensions and scattering amplitudes. The Kardar-Parisi-Zhang (KPZ) equation has been named after Mehran Kardar, notable Iranian physicist.

Dr. Farhad Arbab[166] (with an h-index over 40 in computer science and engineering[167]), is the founder of the Reo programming language for advanced cyber-physical systems. Dr. Reza Malekzadeh is the founder of the Golestan Cohort Study,[168][169] which, based on its findings, was the first to prove the carcinogenicity of opium for international scientific communities.[170] The engineering design for the reengineering of the Arak reactor (IR-40) as a hybrid light-water heavy-water reactor, by Iran's nuclear scientists (under the supervision of Dr. Ali Akbar Salehi), received praise from international experts during the post-JCPOA technical negotiations.[171][172]

Other examples of notable discoveries and innovations by Iranian scientists and engineers (or of Iranian origin) include:

- Siavash Alamouti and Vahid Tarokh: invention of space–time block code

- Moslem Bahadori: reported the first case of plasma cell granuloma of the lung.

- Nader Engheta, inventor of "invisibility shield" (plasmonic cover) and research leader of the year 2006, Scientific American magazine,[173] and winner of a Guggenheim Fellowship (1999) for "Fractional paradigm of classical electrodynamics"

- Reza Ghadiri: invention of a self-organized replicating molecular system, for which he received 1998 Feynman prize

- Maysam Ghovanloo: inventor of Tongue-Drive Wheelchair.[174]

- Alireza Mashaghi: made the first single-molecule observation of cellular protein folding, for which he was named the Discoverer of the Year in 2017.[175][176]

- Karim Nayernia: discovery of spermatagonial stem cells

- Afsaneh Rabiei: inventor[177] of an ultra-strong and lightweight material, known as Composite metal foam|Composite Metal Foam (CMF).[178]

- Mohammad-Nabi Sarbolouki, invention of dendrosome[179]

- Ali Safaeinili: co-inventor of Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS)[180]

- Mehdi Vaez-Iravani: invention of shear force microscopy

- Rouzbeh Yassini: inventor of the cable modem

- Using the Iranian National Observatory Lens Array (INOLA), the first ever attempt at exploring the stellar halo of M33 Galaxy using ultra-deep broad-band imaging was conducted and reported, in 2024.[138]

Many Iranian scientist received internationally recognised awards. Examples are:

- Maryam Mirzakhani: In August 2014, Mirzakhani became the first-ever woman, as well as the first-ever Iranian, to receive the Fields Medal, the highest prize in mathematics for her contributions to topology.[181]

- Cumrun Vafa, 2017 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics[182]

- Nima Arkani-Hamed, 2012 Fundamental Physics Prize winner

- Shekoufeh Nikfar: The awardee of the top women scientists by TWAS-TWOWS-Scopus in the field of Medicine in 2009.[183][184]

- Ramin Golestanian: In August 2014, Ramin Golestanian won the Holweck Prize for his research work in physics.[185]

- Shirin Dehghan: 2006 Women in Technology Award[186]

- Mohammad Abdollahi: The Laureate of IAS-COMSTECH 2005 Prize in the field of Pharmacology and Toxicology and an IAS Fellow. MA is ranked as an International Top 1% outstanding Scientists of the World in the field of Pharmacology & Toxicology according to Essential Science Indicator from USA Thomson Reuters ISI.[187] MA is also known as one of outstanding leading scientists of OIC member countries.[188]

International rankings

- According to the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), Iran increased its academic publishing output nearly tenfold from 1996 to 2004, and has been ranked first globally in terms of output growth rate (followed by China with a 3 fold increase).[189][190] In comparison, the only G8 countries in top 20 ranking with fastest performance improvement are Italy at tenth and Canada at 13th globally.[189][190][191] Iran, China, India and Brazil are the only developing countries among 31 nations with 97.5% of the world's total scientific productivity. The remaining 162 developing countries contribute less than 2.5% of the world's scientific output.[192] Despite the massive improvement from 0.0003% of the global scientific output in 1970 to 0.29% in 2003, still Iran's total share in the world's total output remained small.[193][194] According to Thomson Reuters, Iran has demonstrated a remarkable growth in science and technology over the past one decade, increasing its science and technology output fivefold from 2000 to 2008. Most of this growth has been in engineering and chemistry producing 1.4% of the world's total output in the period 2004–2008. By year 2008, Iranian science and technology output accounted for 1.02% of the world's total output (That is ~340,000% growth in 37 years of 1970–2008).[195] 25% of scientific articles published in 2008 by Iran were international coauthorships. The top five countries coauthoring with Iranian scientists are US, UK, Canada, Germany and France.[196][197]

- A 2010 report by Canadian research firm Science-Metrix has put Iran in the top rank globally in terms of growth in scientific productivity with a 14.4 growth index followed by South Korea with a 9.8 growth index.[198] Iran's growth rate in science and technology is 11 times more than the average growth of the world's output in 2009 and in terms of total output per year, Iran has already surpassed the total scientific output of countries like Sweden, Switzerland, Israel, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Austria or that of Norway.[199][200][201] Iran with a science and technology yearly growth rate of 25% is doubling its total output every three years and at this rate will reach the level of Canadian annual output in 2017.[202] The report further notes that Iran's scientific capability build-up has been the fastest in the past two decades and that this build-up is in part due to the Iraqi invasion of Iran, the subsequent bloody Iran–Iraq War and Iran's high casualties due to the international sanctions in effect on Iran as compared to the international support Iraq enjoyed. The then technologically superior Iraq and its use of chemical weapons on Iranians, made Iran to embark on a very ambitious science developing program by mobilizing scientists in order to offset its international isolation, and this is most evident in the country's nuclear sciences advancement, which has in the past two decades grown by 8,400% as compared to the 34% for the rest of the world. This report further predicts that though Iran's scientific advancement as a response to its international isolation may remain a cause of concern for the world, all the while it may lead to a higher quality of life for the Iranian population but simultaneously and paradoxically will also isolate Iran even more because of the world's concern over Iran's technological advancements. Other findings of the report point out that the fastest growing sectors in Iran are Physics, Public health sciences, Engineering, Chemistry and Mathematics. Overall the growth has mostly occurred after 1980 and specially has been becoming faster since 1991 with a significant acceleration in 2002 and an explosive surge since 2005.[198][199][203][204][205] It has been argued that scientific and technological advancement besides the nuclear program is the main reason for United States worry about Iran, which may become a superpower in the future.[206][207][208] Some in Iranian scientific community see sanctions as a western conspiracy to stop Iran's rising rank in modern science and allege that some (western) countries want to monopolize modern technologies.[74]

- As per US government report on science and engineering titled "Science and Engineering Indicators: 2010" prepared by National Science Foundation, Iran has the world's highest growth rate in Science & Engineering article output with an annual growth rate of 25.7%. The report is introduced as a factual and policy neutral "...volume of record comprising the major high-quality quantitative data on the U.S. and international science and engineering enterprise". This report also notes that the very rapid growth rate of Iran inside a wider region was led by its growth in scientific instruments, pharmaceuticals, communications and semiconductors.[209][210][211][212][213]

- The subsequent National Science Foundation report published in 2012 by US government under the name "Science and Engineering Indicators: 2012", had put Iran first globally in terms of growth in science and engineering article output in the first decade of this millennium with an annual growth rate of 25.2%.[214]

- The latest updated National Science Foundation report published in 2014 by US government titled "Science and Engineering Indicators 2014", has again ranked Iran first globally in terms of growth in science and engineering article output at an annualized growth rate of 23.0% with 25% of Iran's output having been produced through international collaboration.[215][216]

- Iran ranked 49th for citations, 42nd for papers, and 135th for citations per paper in 2005.[217] Their publication rate in international journals has quadrupled during the past decade. Although it is still low compared with the developed countries, this puts Iran in the first rank of Islamic countries.[72] According to a British government study (2002), Iran ranked 30th in the world in terms of scientific impact.[218]

- According to a report by SJR (A Spanish sponsored scientific-data data) Iran ranked 25th in the world in scientific publications by volume in 2007 (a huge leap from the rank of 40 few years before).[219] As per the same source Iran ranked 20th and 17th by total output in 2010 and 2011 respectively.[220][221]

- In 2008 report by Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), Iran ranked 32, 46 and 56 in Chemistry, Physics and Biology respectively among all science producing countries.[222] Iran ranked 15th in 2009 in the field of nanotechnology in terms of presenting articles.[127]

- Science Watch reported in 2008 that Iran has the world's highest growth rate for citations in medical, environmental and ecological sciences.[223] According to the same source, Iran during the period 2005–2009, had produced 1.71% of world's total engineering papers, 1.68% of world's total chemistry papers and 1.19% of world's total material sciences papers.[201]

- According to the sixth report on "international comparative performance of UK research base" prepared in September 2009 by Britain-based research firm Evidence and Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, Iran has increased its total output from 0.13% of world's output in 1999 to almost 1% of world's output in 2008. As per the same report Iran had doubled its biological sciences and health research out put in just two years (2006–2008). The report further notes that Iran by 2008 had increased its output in physical sciences by as much as ten times in ten years and its share in world's total output had reached 1.3%, comparing with US share of 20% and Chinese share of 18%. Similarly Iran's engineering output had grown to 1.6% of the world's output being greater than Belgium or Sweden and just smaller than Russia's output at 1.8%. During the period 1999–2008, Iran improved its science impact from 0.66 to 1.07 above the world's average of 0.7 similar to Singapore's. In engineering Iran improved its impact and is already ahead of India, South Korea and Taiwan in engineering research performance. By 2008, Iran's share of most cited top 1% of world's papers was 0.25% of the world's total.[224]

- As per French government report "L'Observatoire des sciences et des techniques (OST) 2010", Iran had the world's fastest growth rate in scientific article output between 2003 and 2008 period at +219%, producing 0.8% of the world's total material sciences knowledge out put in 2008, the same as Israel. The fastest growing scientific field in Iran was medical sciences at 344% and the slowest growth was of chemistry at 128% with the growth for other fields being biology 342%, ecology 298%, physics 182%, basic sciences 285%, engineering 235% and mathematics at 255%. As per the same report among the countries that produced less than 2% of the world's science and technology, only Iran, Turkey and Brazil had the most dynamic growth in their scientific output, with Turkey and Brazil having a growth rate above 40% and Iran above 200% compared with South Korea and Taiwan growth rates at 31% and 37% respectively. Iran also was among the countries whose scientific visibility was growing fastest in the world such as China, Turkey, India and Singapore though all growing from a low visibility base.[225][226][227]

- According to the latest updated French government report "L'Observatoire des sciences et des techniques (OST) 2014", Iran had the world's fastest growth rate in scientific production output in the period between 2002 and 2012, having increased its share of world's total scientific output by +682% in the said period, producing 1.4% of world's total science and ranking 18th globally in terms of its total scientific output. Meanwhile, Iran also ranks first globally for having increased its share in the world's high impact (top 10%) publications by +1338% between 2002 and 2012 and similarly ranks first globally as well for increasing its global scientific visibility through having its share of international citations increased by +996% in the above period. Iran also ranks first globally in this report for the growth rate in scientific production of individual fields by having increased its science output in Biology by +1286%, in Medicine by +900%, in Applied biology and Ecology by +816%, in Chemistry by +356%, in Physics by +577%, in Space sciences by +947%, in Engineering sciences by +796% and in Mathematics by +556%.[228][229][230]

- A bibliometric analysis of middle east was released by professional division of Thomson Reuters in 2011 titled "Global Research Report Middle East" comparing scientific research in middle eastern countries with that of the world for the first decade of this century. The study findings rank Iran at second position after Turkey in terms of total scientific output with Turkey producing 1.9% of the world's total science output while Iran's share of world's total science output was at 1.3%. Total scientific output of 14 countries surveyed including Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Yemen was just 4% of the world's total output; with Turkey and Iran producing the bulk of scientific research in the region. In terms of growth in scientific research, Iran was ranked first with 650% increase of its share in world's output and Turkey second with a growth of 270%. Turkey increased its research publication rate from 5000 papers in year 2000 to nearly 22000 in the year 2009, while Iran's research publication started from a lower point of 1300 papers in year 2000 and grew to 15000 papers in the year 2009 with a notable surge in Iranian growth after year 2004. In terms of production of highly cited papers, 1.7% of all Iranian papers in mathematics and 1.3% of papers in engineering fields attained highly cited status defined as most cited top 1% of world's publications, exceeding the world's average in citation impact for those fields. Overall Iran produces 0.48% of the world's highly cited output in all fields just about half of what would be expected for parity at 1%. Comparative figures for other countries following Iran in the region are: Turkey producing 0.37% of the world's highly cited papers, Jordan 0.28%, Egypt 0.26% and Saudi Arabia 0.25%. External scientific collaboration accounted for 21% of the total research projects undertaken by researchers in Iran with largest collaborators being United States at 4.3%, United Kingdom at 3.3%, Canada 3.1%, Germany 1.7% and Australia at 1.6%.[231]

- In 2011, world's oldest scientific society and Britain's leading academic institution, the Royal Society in collaboration with Elsevier published a study named "Knowledge, networks and nations" surveying global scientific landscape. According to this survey Iran has the world's fastest growth rate in science and technology. During the period 1996–2008, Iran had increased its scientific output by 18 folds.[33][34][36][37][232][233][234][235][236][237][238]

- As per WIPO's report titled "World Intellectual Property Indicators 2013", Iran ranked 90th for patents generated by Iranian nationals all over the world, 100th in industrial design and 82nd in trademarks, positioning Iran below Jordan and Venezuela in this regard but above Yemen and Jamaica.[239][240]

- According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) in 2023, Iran ranks among the top 10 countries in future critical technology.[241][242]

Iranian journals listed in the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI)

According to the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), Iranian researchers and scientists have published a total of 60,979 scientific studies in major international journals in the last 19 years (1990–2008).[243][244] Iran science production growth (as measured by the number of publications in science journals) is reportedly the "fastest in the world", followed by Russia and China respectively (2017/18).[245]

- Acta Medica Iranica

- Applied Entomology and PhytoPathology

- Archives of Iranian Medicine

- DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences

- Iranian Biomedical Journal

- Iranian Journal of BioTechnology

- Iranian Journal of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering

- Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences-English

- Iranian Journal of Plant Pathology

- Iranian Journal of Science and Technology

- Iranian Polymer Journal

- Iranian Journal of Public Health

- Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

- Iranian Journal of Reproductive Medicine

- Iranian Journal of Veterinary Medicine

- Iranian Journal of Fuzzy Systems

- Journal of Entomological Society of Iran

- Plant Pests & Diseases Research Institute Insect Taxonomy Research Department Publication

- The Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society

- Rostaniha (Botanical Journal of Iran)

See also

General

- Higher Education in Iran

- List of Iranian Research Centers

- List of contemporary Iranian scientists, scholars, and engineers (modern era)

- List of Iranian scientists

- Economy of Iran

- Industry of Iran

- Iran's brain drain

- International rankings of Iran

- Intellectual Movements in Iran

- Base isolation from Iran

- Science in newly industrialized countries

- Composite Index of National Capability

- Islamic Golden Age

- Persian philosophy

Prominent organizations

- Institute of Standards and Industrial Research of Iran

- Atomic Energy Organization of Iran

- Iranian Space Agency

- Iranian Chemists Association

- The Physical Society of Iran

- Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology

- Iran National Science Foundation

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 387–409, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 387–409, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

References

- ^ "Iran issues license on its coronavirus vaccine". Trend.Az. 14 June 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Kazemi, Abbas Varij; Dehnavi, Azadeh Dehqhan (26 February 2017). "The New Academic Proletariat in Iran". Critique. 45 (1–2): 141–158. doi:10.1080/03017605.2016.1268455. ISSN 0301-7605.

- ^ Andy Coghlan. "Iran is top of the world in science growth". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ward English, Paul (21 June 1968). "The Origin and Spread of Qanats in the Old World". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 112 (3): 170–181. JSTOR 986162.

- ^ "Riddle of 'Baghdad's batteries'". BBC News. 27 February 2003. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Scott, David A. (2002). Copper and Bronze in Art: Corrosion, Colorants, Conservation. Getty Publications. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-89236-638-5. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Stone, Elizabeth (23 March 2012). "Archaeologists Revisit Iraq". Science Friday (Interview). Interviewed by Flatow, Ira. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

My recollection of it is that most people don't think it was a battery. ... It resembled other clay vessels ... used for rituals, in terms of having multiple mouths to it. I think it's not a battery. I think the people who argue it's a battery are not scientists, basically. I don't know anybody who thinks it's a real battery in the field.

- ^ Glick, Thomas F., Steven Livesey, and Faith Wallis. Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia. Routledge, 2014, 519

- ^ Geography, Landscape and Mills – Pennsylvania State University

- ^ Hill, Donald. Islamic Science and Engineering. 1993. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0455-3 p.222

- ^ Scott L. Montgomery; Alok Kumar (12 June 2015). A History of Science in World Cultures: Voices of Knowledge. Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-317-43906-6.

- ^ Bennison, Amira K. (2009). The great caliphs : the golden age of the 'Abbasid Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-300-15227-2.

- ^ Casulleras, Josep (2007). "Banū Mūsā". In Thomas Hockey (ed.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 92–4. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0.

- ^ C. Elgood. A Medical history of Persia. Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 173

- ^ Gorji A; Khaleghi Ghadiri M (December 2002). "History of headache in medieval Persian medicine". Lancet Neurology. 1 (8): 510–5. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00226-0. PMID 12849336. S2CID 1979297.

- ^ a b c d Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Tubbs, R. Shane (April 2007). "The history of anatomy in Persia". Journal of Anatomy. 210 (4): 359–378. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00711.x. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 2100290. PMID 17428200.

- ^ Edward Granville Browne. Islamic Medicine, Goodword Books, 2002, ISBN 81-87570-19-9. p. 79

- ^ "Archives of Iranian Medicine". Ams.ac.ir. 18 August 1905. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Introduction to Urmia University". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- ^ Gemson, Claire (13 October 2007). "1,001 inventions mark Islam's role in science". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, UK.

- ^ Gingerich, Owen (April 1986). "Islamic Astronomy". Scientific American. 254 (4): 74–83. Bibcode:1986SciAm.254d..74G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0486-74. ISSN 0036-8733.