Dorothea Chalmers Smith

Elizabeth Dorothea Chalmers Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1874 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | 1944 (aged 69–70) |

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow |

| Known for | Doctor and Suffragette |

| Spouse | Reverend William Chalmers Smith |

Elizabeth "Dorothea" Chalmers Smith née Lyness (1874 – 1944) was a pioneer medical doctor and a militant Scottish suffragette. She was imprisoned for eight months for breaking and entering, and attempted arson, where she went on hunger strike.

Early life

[edit]Born in Dennistoun, Glasgow, Elizabeth Dorothea Lyness graduated from medicine from the University of Glasgow in 1894, and worked at the Royal Samaritan Hospital for Women in Glasgow.[1]

She married Reverend William Chalmers Smith, minister of Calton Church, Glasgow in 1901. They had six children born between 1900 and 1911.

Political Activity

[edit]Chalmers Smith joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1912, but her enthusiasm for extreme militancy was not welcomed by her husband, who believed adamantly that a woman's place was in the home.[2]

Chalmers Smith, alongside artist Ethel Moorhead, attempted to set fire to a house at 6 Park Gardens in Glasgow on 23 July 1913.[3] They were caught red-handed by multiple witnesses.[4] In one room firefighters found matches, firelighters, six flasks of paraffin, candles, and a postcard bearing the words: 'A protest against Mrs Pankhurst's re-arrest'.[2][4]

The case was tried in the High Court at Jail Square and hundreds of Suffragettes attended the trial. Chalmers Smith and Moorhead both conducted their own defence and refused to plead. Moorhead interrupted the Judge saying "We do not want to hear any more. We refused to listen to you. Please sentence us."[2]

When both women were sentenced to eight-months imprisonment, the women rose from all sections of the court and protested, crying out "Pitt Street, Pitt Street" whilst others starting throwing apples at the Judge and counsel.[5]

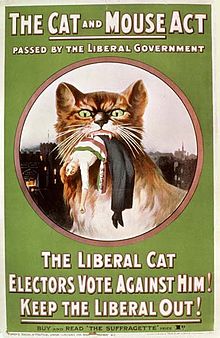

Both women went on hunger strike immediately. When they became physically weak they were released from prison under the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act , known as the Cat and Mouse Act, which was introduced in April 1913, and allowed for the re-arrest of prisoners once their health improved.[5]

Detectives were posted on the door of her house to make sure that she did not escape. She managed to escape on occasion by dressing up in her younger sister's school uniform.

Chalmers Smith had been given a Hunger Strike Medal 'for Valour' by WSPU.

Later life

[edit]Chalmers Smith and her husband divorced after the First World War, it is said due to pressure from the Kirk Session (parish group) at a time that it was difficult for a Church of Scotland minister to do so. She left with her three daughters, but she was not allowed to see her three sons again.[2]

After the Great War, Chalmers Smith worked in the newly established child welfare clinics in Glasgow. She did pioneering work in child-care and raised her daughters to be doctors. She died in 1944, and her silver WSPU Hunger Strike medal was donated to the People's Palace by one of her daughters. These medals were first presented by the WSPU at a ceremony in August 1909.[6]

The Suffragette Oak on Kelvinway was planted in 1918 to celebrate women’s first opportunity to vote in a general election and stands as a memorial to the likes of Helen Crawfurd, Dorothea Chalmers Smith, Jessie Stephen and Frances McPhun.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Crawford, Elizabeth (2 September 2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge. ISBN 1135434018.

- ^ a b c d Atkinson, Diane (8 February 2018). Rise Up Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408844069.

- ^ ABACUS, Scott Graham -. "TheGlasgowStory: 1830s to 1914: Learning and Beliefs: Women's Suffrage". www.theglasgowstory.com. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Introduction to Women's Suffrage in Scotland". www.scan.org.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ a b "A nation aflame with passion". HeraldScotland. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Collecting Suffrage: The Hunger Strike Medal". Woman and her Sphere. 11 August 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Thanks for the memories: Glasgow women who blazed a trail". Stirling News. Retrieved 22 February 2018.