Dyrham Park

| Dyrham Park | |

|---|---|

Lower part of the park and east front of the house and orangery | |

| Type | Country house |

| Location | Dyrham and Hinton, Gloucestershire |

| Coordinates | 51°28′48″N 2°22′24″W / 51.4801°N 2.3734°W |

| OS grid reference | ST742757 |

| Built | 1692-1704 |

| Architect |

|

| Architectural style(s) | Baroque |

| Owner | National Trust |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Dyrham House |

| Designated | 17 Sep 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1212039 |

| Official name | Dyrham Park |

| Designated | 30 Apr 1987 |

| Reference no. | 1000443 |

Dyrham Park (/ˈdɪrəm/) is a baroque English country house in an ancient deer park near the village of Dyrham in South Gloucestershire, England. The house, with the attached orangery and stable block, is a Grade I listed building, while the park is Grade II* listed on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.

The current house was built for William Blathwayt in stages during the 17th and early 18th centuries on the site of a previous manor house, with the final facade being designed by William Talman. It contains art works and furniture from around the world, particularly Holland, and includes a collection of Dutch Masters. The house is linked to the 13th-century church of St Peter, also Grade I listed, where many of the Blathwayt family are buried. The house is surrounded by 274 acres (111 ha) of formal gardens, and parkland which supports a herd of fallow deer. The grounds, which were originally laid out by George London and later developed by Charles Harcourt Masters, include water features and statuary.

The house and estate are now owned by the National Trust and underwent extensive renovation in 2014 and 2015. They are open to the public on some days and host events and attractions, including open-air concerts. They have also been used as a location for film and television productions.

History

[edit]

The Manor of Dyrham has been recorded since the Domesday Book of 1086, when there were 34 households.[1] The first lord of the manor to be resident may have been William Denys, who was an Esquire of the Body to Henry VIII and later High Sheriff of Gloucestershire. He was granted the licence to empark 500 acres (200 ha) of Dyrham in 1511, although not all of this area was enclosed.[2] This meant that he could enclose the land with a wall or hedge bank and maintain a captive herd of deer within the park, over which he had exclusive hunting rights;[3] the name "Dyrham" is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word dirham, an enclosure for deer.[4] The estate was sold to the Wynter family in 1571 and Sir George Wynter was allowed to empark further land in 1620.[3]

In 1689, the estate was acquired through marriage by William Blathwayt, who was Secretary at War to William III. He retained the existing Tudor building and expanded it in stages.[5] The west front of 1692 was commissioned from Huguenot architect Samuel Hauduroy,[6] and includes an Italianate double staircase leading from the terrace to the grounds.[7] In 1698, a stable block was added with space for 26 horses and servants' quarters above around a courtyard.[5] The east front of 1704 was designed by William Talman, architect of Chatsworth.[6] The construction of the east wing included demolition of the remains of the original Tudor house and the addition of a statue of an eagle on the roof.[5]

Dyrham next became a showcase of Dutch decorative arts.[8][9] The collection includes delftware, paintings, and furniture. Eighteenth-century additions include furniture by Gillow and Linnell. The interiors have remained little altered since decorated by Blathwayt. The gardens were designed by George London in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.[3]

The Blathwayt family owned the house until 1956, when the government acquired it. During the Second World War it was used for child evacuees while rented by Anne, Baroness Islington, the widow of The 1st Baron Islington (1866-1936), a former Governor of New Zealand. Lady Islington redecorated many of the rooms.[10][11] The National Trust acquired it in 1961.[12] In 2015, major renovation work included replacing the roof. Part of the cost was met from a Heritage Lottery Fund grant of £85,000.[12] While the repairs were in progress, visitors could view the house from a rooftop walkway.[13][14] In 2020, the National Trust published a report which examined the connections of its properties to the British Empire. The report's authors noted that Dyrham Park was owned by several individuals who were involved in administering colonies of the British Empire, including Blathwayt, who was a prominent official in the Southern Department.[15][16]

Architecture

[edit]House

[edit]

The limestone building has slate and lead roofs above the attics. The two-storey west front, which was built in the 1690s, has three bays of each side of the central doorway, which has Doric columns, with smaller pavilions at the ends of the wings.[6] One of the wings creates a covered passageway to the church of St Peter.[7] The east front, which was added around 1704, has shallow projecting wings and a central door under a balustrade with an Italianate double staircase leading down to the lawns. A central pedestal is inscribed "virtute et veritate". Above it is an eagle statue, carved by John Harvey of Bath, representing the family crest of the Blathwayt family.[6]

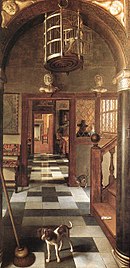

The interior is sumptuously decorated with wood panelling and tiles of Delftware.[7] The collection of artworks and artifacts includes furniture, china and pictures with a strong Dutch influence.[17] The china includes a pair of tulip vases made in the 1680s.[18] The state bed, with crimson and yellow velvet hangings, was made in Anglo-Dutch style around 1704.[7] The entrance hall is hung with bird paintings by Melchior d'Hondecoeter and throughout the house are landscape and still lifes by Abraham Storck, Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten, David Teniers the Younger, Melchior d'Hondecoeter, and other Dutch Masters. Hoogstratens "View of a Corridor" has been hung in a doorway as the artist originally intended.[19] Blathwayt's travels are also represented by paintings by Spanish artists such as Bartolomé Esteban Murillo and a staircase made of walnut from his estates as auditor general of the Colony of Virginia.[20] Many of these were brought to Dyrham by George William Blathwayt after he inherited the house in 1844.[7] There are also artifacts from Blathwayt's journeys to other parts of the world, particularly Jamaica.[21]

Orangery and stable block

[edit]On the south eastern side of the house is an orangery, which was built as a greenhouse in 1701 and has a glazed roof which was added around 1800 by Humphrey Repton.[22] The orangery hides the view of the servants' quarters from the main house.[7] The servants' quarters was revised and modernised in the 1840s. It contains the kitchen, dairy, bakehouse and several larders for raw and cooked meat. There is also a servants' hall where the staff would take their meals and a tenants' hall which was used by the tenant farmers to eat on the days when they came to pay their rent.[23] In addition to the designs for the house, William Talman created the large 15-bay stable block.[24] It is now used as a tea-room for visitors.[25]

Church

[edit]| St Peter's Church | |

|---|---|

| |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Church of St Peter Dyrham and Hinton |

| Designated | 15 Aug 1985 |

| Reference no. | 1289711 |

The Anglican parish church of St Peter was originally built in the mid 13th century and had a three-stage tower added in the 15th, however it was extensively restored when the main house was built in the late 17th century. The church consists of a north and south aisle, chancel and south west porch with the tower to the west.[26] In the south aisle are encaustic tiles dating from the 13th century.[27] The font is Norman while the pulpit is Jacobean. There is also a 16th-century Flemish altar triptych.[26]

The church is not owned by the National Trust but is closely associated with the rest of the estate and has the tombs and memorials for many owners of the house.[28] The parish is part of the benefice of Wick with Doynton and Dyrham, within the Diocese of Bristol.[29]

Grounds

[edit]

The house is set in 274 acres (111 ha) of gardens and parkland, which was home to a herd of 200 fallow deer[30] until they were culled due to the spread of bovine tuberculosis in 2021. [31] The National Trust introduced a new herd of 26 deer in April 2024. Many of the walls and gatepiers were added in the late 18th century.[32][33][34][35][36] There is statuary in the grounds, including a statue of Neptune by Claude David, about 320 metres (1,050 ft) east of the house.[37] Artificial lakes and cascades of water are also a feature.[38]

The gardens were designed by George London in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.[3] They included a formal Dutch water garden, but most of the features were replaced in the late 18th century with designs by Charles Harcourt Masters.[7] The park is listed Grade II* on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[39]

Public access

[edit]

The house and gardens are open to the public on certain days, and the grounds are open all year long. A bus takes visitors from the car park down to the house, gardens, tea room and shop. The bus road can be walked down for access to the house or there is an easy walk to the house down grassy slopes. There is no car parking at the house itself. Dogs are not permitted in the park, but there is an exercise area for dogs near the car park. Events within the park include music concerts, open-air theatre productions, guided tours of the house, park and garden, and other attractions.[40][41]

Film and television

[edit]Dyrham Park was one of the houses used as a filming location for the 1993 Merchant Ivory film The Remains of the Day (others included Badminton House and Powderham Castle).[42] The house was used for outdoor and garden scenes in the 1999 BBC mini-series Wives and Daughters.[43] In 2003, it was the filming location for the BBC One series Servants.[44] An aerial view of Dyrham Park was featured in the opening title sequence of the 2008 film Australia.[45]

In September 2010, the BBC filmed scenes for the Doctor Who sixth series episode "Night Terrors" at Dyrham Park.[46][47][48]

Dyrham Park was also used for scenes in The Crimson Field by the BBC in 2014, and Sanditon on ITV in 2019.[49]

The BBC series Poldark filmed scenes at Dyrham Park, as the home of George Warleggan, between 2015 and 2018.[50]

The HBO series Industry filmed on the estate for season 3.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dyrham in the Domesday Book

- ^ "Dyrham Park, Dyrham and Hinton, Near Bath, England". Parks and Gardens UK. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Dyrham Park, Dyrham and Hinton, Near Bath, England". Parks and Gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Ekwall (1960). The Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford. p. 155.

- ^ a b c Garnett, Oliver (2000). Dyrham Park. National Trust. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1843590965.

- ^ a b c d Historic England. "Dyrham House (1212039)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Greeves, Lydia (2013). Houses of the National Trust. London: National Trust. pp. 128–129. ISBN 9781907892486.

- ^ "A View through a House". National Trust Collections. National Trust. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "History of Dyrham Park". National Trust. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Garnett, Oliver (2000). Dyrham Park. National Trust. p. 32. ISBN 978-1843590965.

- ^ "History talk focuses on wartime nursery and children's homes". University of the West of England. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Dyrham Park secures Heritage Lottery Fund investment". National Trust. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Dyrham Park aerial walkway to view roof replacement work". BBC News. 6 May 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "Dyrham Mansion near Bath". Integral Engineering. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Britain's Idyllic Country Houses Reveal a Darker History". The New Yorker. 13 August 2021.

- ^ Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, Including Links with Historic Slavery

- ^ "Dyrham Park, Gloucestershire (Accredited Museum)". National Trust. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Garnett, Oliver (2000). Dyrham Park. National Trust. p. 14. ISBN 978-1843590965.

- ^ Garnett, Oliver (2000). Dyrham Park. National Trust. p. 12. ISBN 978-1843590965.

- ^ Garnett, Oliver (2000). Dyrham Park. National Trust. p. 8. ISBN 978-1843590965.

- ^ Nelson, Louis (2016). Architecture and Empire in Jamaica. Yale University Press. p. 237. ISBN 9780300214352. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Orangery attached to south east of Dyrham House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ Garnett, Oliver (2000). Dyrham Park. National Trust. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-1843590965.

- ^ "Stable Block attached to south of Dyrham House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Dyrham Park tea-room". National Trust. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Church of St. Peter". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "The Wheel of Life". Weston-super-Mare Archaeological and Natural History Society. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "St Peter's Dyrham". Wick Benefice. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "St Peter, Dyrham". A Church Near You. Church of England. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Deer at Dyrham Park". National Trust. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Entire herd of deer culled at National Trust estate". ITV News. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Wall, basin, gate piers and steps about 17 metres east of Stable Block". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Wall and gates about 200 metres west of Dyrham House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "4 gate piers and railings forming screen between west elevation of Orangery and east elevation of Stable Block". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Wall about 200 metres west of Stable Block attached to south of Dyrham House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Remains of wall about 200 metres north of Statue of Neptune". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Statue of Neptune about 320 metres east of Dyrham House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Small cascade and 2 lakes about 50 metres west of Stable Block attached to south of Dyrham House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Dyrham Park". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "School summer holidays at Dyrham Park". National Trust. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "What's on at Dyrham Park". National Trust. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ Bingham, Jane (2010). The Cotswolds: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780195398755. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "The Cotswolds on Film – TV". Loving the Cotswolds. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Productions Filmed in the Area of Bath since 1931" (PDF). Bath Film Office. Bath and North East Somerset. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ "Dyrham Park". Nature Conservation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ Golder, Dave (27 August 2011). "Doctor Who "Night Terrors" Preview: Daniel Mays Interview". SFX. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "Night Terrors". Dr Who Locations. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Goodwin, Ben. "Hollywood heritage". Heritage Open Days. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Dyrham Park features in Sanditon". National Trust. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Poldark Filming Locations: Grand Houses Used in Poldark". Finf that location. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

External links

[edit]- Dyrham Park at the National Trust