Eider Canal

| Eider Canal | |

|---|---|

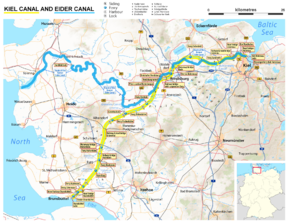

Map of the Eider Canal (blue) and succeeding Kiel Canal in Schleswig-Holstein | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 107 miles (172 km) (Man-made segment ran for 26 miles (42 km)[1]) |

| Locks | 6 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 23 ft (7.0 m) |

| Status | Replaced by Kiel Canal |

| History | |

| Date of act | 14 April 1774 |

| Construction began | 1776 |

| Date completed | 1784 |

| Date closed | 1887 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Tönning (North Sea) |

| End point | Kiel (Baltic Sea) |

The Eider Canal (also called the Schleswig-Holstein Canal) was an artificial waterway in southern Denmark (later northern Germany) which connected the North Sea with the Baltic Sea by way of the rivers Eider and Levensau. Constructed between 1777 and 1784, the Eider Canal was built to create a path for ships entering and exiting the Baltic that was shorter and less storm-prone than navigating around the Jutland peninsula. In the 1880s the canal was replaced by the enlarged Kiel Canal, which includes some of the Eider Canal's watercourse.[2]

Names

[edit]The canal's watercourse followed the border between the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, and from the time of its construction it was known as the "Schleswig-Holstein Canal". After the First Schleswig War, the Danish government renamed the waterway the "Eider Canal" to resist the German nationalist idea of Schleswig-Holstein as a single political entity; but, when the region passed into Prussian control after the Second Schleswig War, the name was reverted to the "Schleswig-Holstein Canal." In modern historiography the canal is referred to by either name.[3]

History

[edit]As early as 1571 Duke Adolf I of Holstein-Gottorp proposed to build an artificial waterway across Schleswig-Holstein by connecting an eastward bend of the River Eider to the Baltic Sea, so as to compete with the nearby Stecknitz Canal for merchant traffic.[4] At the time the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp was a vassal of the Kingdom of Denmark, but the dukes of Schleswig-Holstein were perennial enemies to their Danish suzerains, and the political fragmentation of the region and the ongoing conflict over its rightful rule posed an insurmountable obstacle to such a large project.[5] The prospect of a canal was again raised in the 1600s under King Christian IV and Duke Frederick III.[6]

After the incorporation of Holstein into the Danish crown by the 1773 Treaty of Tsarskoye Selo, geopolitical conditions at last permitted a canal's construction and operation. Surveying and planning for the canal began in 1773, with a preliminary plan for the canal proposed in February 1774. On 14 April 1774, King Christian VII of Denmark issued a cabinet order establishing a Canal Commission to oversee the construction, led by Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann.[6][7]

Construction

[edit]

Preparations for the canal began in 1776 with dredging of the lower Eider between Friedrichstadt and Rendsburg. The artificial canal was then excavated and fitted with locks to allow ships to cross the peninsula's drainage divide and descend to the Kieler Förde on the Baltic coast. Construction on the artificial segment, eventually 34 kilometres (21 mi) long, began in July 1777 at Holtenau on the Baltic shore north of Kiel, proceeding to Knoop by the following autumn. This section partly followed the small river Levensau that emptied into the Kieler Förde. The section from Knoop to Rathmannsdorf was built between 1778 and 1779, and the highest segment (connecting to the Flemhuder See) was completed in 1780. Finally, locks were installed along the upper Eider's natural course, starting at Rendsburg, to raise and deepen the river and make its upper reaches navigable as far as the western end of the artificial canal.[3]

Including 130 kilometres (81 mi) of the Eider and a 9-kilometre (5.6 mi) stretch passing through the Upper Eider Lakes at Rendsburg, the shipping route covered a total length of 173 kilometres (107 mi). Between the Baltic and the upper Eider there was a difference in elevation of about 7 metres (23 ft), which required the construction of six locks, located at Rendsburg, Kluvensiek, Königsförde, Rathmannsdorf, Knoop, and Holtenau (from west to east). All construction work was completed by the fall of 1784.[1][8]

Replacement by Kiel Canal

[edit]The Eider Canal soon carried a considerable volume of shipping, and as decades passed the growing number and size of the ships wanting to make the crossing strained the canal's capacity. The winding course of the Eider and the need to navigate through the Frisian Islands at the canal's west end added to the travel time, and the drafts of late-nineteenth-century warships precluded their using the canal. In 1866 the Second Schleswig War resulted in Schleswig-Holstein's becoming part of Prussia, after which the German government explored a number of options for renovating or replacing the canal to improve commercial and military access to the Baltic.[9]

In 1887 Kaiser Wilhelm I inaugurated construction on a new canal through Schleswig-Holstein called the Kiel Canal. Though the new canal's western end is farther south (at the mouth of the Elbe), much of the Eider Canal's watercourse was reused for the new waterway. Many sections were deepened, and some were straightened, cutting off bends that still exist as oxbow lakes. The new canal was opened by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1895.[10]

Packing houses

[edit]

In 1783, as part of the canal's development, three warehouses (called "packing houses" in German) were built along the watercourse: one at the Kiel-Holtenau lock, one at the Rendsburg lock, and one in the harbor area of Tönning. These structures allowed for the storage and handling of bulk goods transiting the canal, such as wool, cereals, coffee and salt. All three packing houses are made of bricks over a timber frame, with three full floors and an attic. The packing houses in Holtenau and Tönning are comparable in size, with approximately 4,000 square metres (43,000 sq ft) of floor space each; the Rendsburg packing house is substantially smaller than the other two.[8]

Course of the Canal

[edit]The canal's eastern end was in the Kieler Förde at the mouth of the river Levensau. The canal ran westward in the small river's natural bed to the first lock, by the Holtenau packing house, and on to the second, by Gut Knoop. At both of these sites there were pre-existing bridges across the Levensau. Then, for a short distance the canal separated from the Levensau to run northwest from Achtstückenberg to the third lock at Rathmannsdorf, where the canal reached its maximum elevation of 7 metres (23 ft) above sea level. The section of the canal from Knoop to the Rathmannsdorf lock has been preserved, with remains of the locks still standing. West of Rathmannsdorf the canal rejoined the riverbed of the Levensau and followed it westward until connecting with the Flemhuder See, which provided the reservoir of water for the operation of the canal's most elevated segment.[11]

From the Flemhuder See the canal proceeded westward to the south of Gut Rosenkranz until it came to a fourth lock at Klein Königsförde. From there it followed a long stretch of the Eider, a small detour northward from Königsförde to Grünhorst, and then a bend southward on Sehestedt to the fifth lock at Kluvensiek. The section from Klein Königsförde via Kluvensiek to Hohenfelde is still preserved today, along with remains of the lock system. From here the canal followed the Eider's natural river bed, flowing past Schirnau, Lehmbek, and Borgstedt before finally coming to Rendsburg, where the sixth and final lock stood, along with a second packing house. From Rendsburg the waterway followed the natural river Eider down to its confluence with the North Sea at Tönning, where a third packing house was built.[11]

Specifications

[edit]The artificial canal had a length of 34 kilometres (21 mi), a water-level width of 28.7 metres (94 ft), a bottom width of 18 metres (59 ft) and a depth of 3.45 metres (11.3 ft), making a water-carrying cross-section of 83 square metres (890 sq ft). Ships of up to 28.7 metres (94 ft) length, 7.5 metres (25 ft) width, 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) draft and 140 tonnes (310,000 lb) displacement were allowed to pass through the channel.[9][12] A passage through the canal and along the Eider took three days or more; in unfavorable wind ships were drawn by horses on the accompanying towpaths. In more than one hundred years of operation, the canal was crossed by about 300,000 ships.[4]

Preservation

[edit]

Significant parts of the former Eider Canal, along with four of its locks, are now in protected areas as important elements of the historical and cultural landscape in Schleswig-Holstein. The Holtenau lock, the Rathmannsdorf lock by Altenholz, the lock at Klein Königsförde in Krummwisch, and the Kluvensiek lock in Bovenau (along with its drawbridge) are now under cultural monument protection. Segments of the old canal in Bovenau and in Altenholz have been designated as landscape conservation areas.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Vernon-Harcourt, Leveson Francis (1896). Rivers and Canals (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 571.

- ^ "Eider River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Der Alte Eiderkanal (Schleswig-Holsteinischer Canal)". Geschichte Kiel-Holtenaus (in German). Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ a b c Watty, Fred (2012). Kiel and the fjord region. Sutton Verlag GmbH. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9783954000616. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ Ward, Sir Adolphus William; Prothero, George Walter; Leathes, Sir Stanley Mordaunt; Benians, Ernest Alfred (1908). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. 5. Macmillan. p. 580. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Geschichte des Eiderkanals". Canal-Verein e.V. (in German). Archived from the original on 16 July 2018.

- ^ Jessen-Klingenberg, Manfred (March 2010). "Der Schleswig-Holsteinische Kanal − Eiderkanal. Vorgeschichte, Entstehung, Bedeutung". Mitteilungen der Kieler Gesellschaft für Stadtgeschichte (in German) (85): 116.

- ^ a b Witte, Christiane (2008). Das Tönninger Packhaus – 225 Jahre alt (in German).

- ^ a b Hansen, Christian (1860). The Great Holstein Ship-canal from Brunsbüttel to the Bay of Neustadt, for Uniting the Northsea and the Baltic. p. 6. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "The history of the Kiel Canal". City of Kiel. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ a b Quedenbaum, Gerd (1984). Im Spiegel der Lexika: Eider, Kanal und Eider-Canal (in German). Düsseldorf: Verlag Butendörp. ISBN 9783921908051.

- ^ Jensen, Waldemar (1970). "Vorgeschichte des Kanalbaus". Der Nord-Ostsee-Kanal: Eine Dokumentation zur 75jährigen Wiederkehr der Eröffnung (in German). Neumünster: Verlag Wachholtz. p. 40.

External links

[edit] Media related to Eider Canal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eider Canal at Wikimedia Commons