Enchondroma

| Enchondroma | |

|---|---|

| |

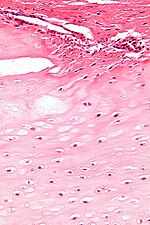

| Micrograph of an enchondroma. H&E stain. |

Enchondroma is a type of benign bone tumor belonging to the group of cartilage tumors.[1][2] There may be no symptoms,[3] or it may present typically in the short tubular bones of the hands with a swelling, pain or pathological fracture.[4]

Diagnosis is by X-ray, CT scan and sometimes MRI.[4] Most occur as a less than three centimetre size single tumor. When several occur in one long bone or several bones, the syndrome is called enchondromatosis.[4]

Where there are no symptoms, treatment is often not needed.[4] If treatment is required, curettage may be performed.[4] Less than 1% become malignant, unless part of a syndrome.[4]

They comprise around 30% of cartilage tumors.[5] 90% of tumors in the hand are enchondromas.[6]

Symptoms and signs

[edit]

Individuals with an enchondroma often have no symptoms at all. The following are the most common symptoms of an enchondroma. However, each individual may experience symptoms differently. Symptoms may include:[citation needed]

- Pain that may occur at the site of the tumor if the tumor is very large, or if the affected bone has weakened causing a fracture of the affected bone

- Enlargement of the affected finger

- Slow bone growth in the affected area

The symptoms of enchondroma may resemble other medical conditions or problems.

Associated conditions

[edit]An enchondroma may occur as an individual tumor or several tumors. The conditions that involve multiple lesions include the following:[citation needed]

- Ollier disease (enchondromatosis) – when multiple sites in the body develop the tumors. Ollier disease is very rare.

- Maffucci's syndrome – a combination of multiple tumors and angiomas (benign tumors made up of blood vessels).

Cause

[edit]While the exact cause of enchondroma is not known, it is believed to occur either as an overgrowth of the cartilage that lines the ends of the bones, or as a persistent growth of original, embryonic cartilage.[citation needed]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Enchondroma is a type of benign bone tumor that originates from cartilage. The exact etiology of it is not known. An enchondroma most often affects the cartilage that lines the inside of the bones. The bones most often involved with this benign tumor are the miniature long bones of the hands and feet. It may, however, also involve other bones such as the femur, humerus, or tibia. While it may affect an individual at any age, it is most common in adulthood. The occurrence between males and females is equal. It is not very likely that the enchondroma will grow back in the same spot; the rate is less than ten percent.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

[edit]Because an individual with an enchondroma has few symptoms, diagnosis is sometimes made during a routine physical examination, or if the presence of the tumor leads to a fracture. In addition to a complete medical history and physical examination, diagnostic procedures for enchondroma may include the following:[citation needed]

- X-ray – On plain film, an enchondroma may be found in any bone formed from cartilage. They are lytic lesions that usually contain calcified chondroid matrix (a "rings and arcs" pattern of calcification), except in the phalanges. They may be central, eccentric, expansile or nonexpansile.

Differentiating an enchondroma from a bone infarct on plain film may be difficult. Generally, an enchondroma commonly causes endosteal scalloping while an infarct will not. An infarct usually has a well-defined, sclerotic serpentine border, while an enchondroma will not. When differentiating an enchondroma from a chondrosarcoma, the radiographic image may be equivocal; however, periostitis is not usually seen with an uncomplicated enchondroma.[citation needed]

- radionuclide bone scan – a nuclear imaging method to evaluate any degenerative and/or arthritic changes in the joints; to detect bone diseases and tumors; to determine the cause of bone pain or inflammation. This test is to rule out any infection or fractures.

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[7] – a diagnostic procedure that uses a combination of large magnets, radiofrequencies, and a computer to produce detailed images of organs and structures within the body. This test is done to rule out any associated abnormalities of the spinal cord and nerves.

- computed tomography scan (Also called a CT or CAT scan.) – a diagnostic imaging procedure that uses a combination of x-rays and computer technology to produce cross-sectional images (often called slices), both horizontally and vertically, of the body. A CT scan shows detailed images of any part of the body, including the bones, muscles, fat, and organs. CT scans are more detailed than general x-rays.

Treatment

[edit]Specific treatment for enchondroma is determined by a physician based on the age, overall health, and medical history of the patient. Other considerations include:

- extent of the disease

- tolerance for specific medications, procedures, or therapies

- expectations for the course of the disease

- opinion or preference of the patient

Treatment may include:

- surgery (in some cases, when bone weakening is present or fractures occur)

- bone grafting – a surgical procedure in which healthy bone is transplanted from another part of the patient's body into the affected area.

If there is no sign of bone weakening or growth of the tumor, observation only may be suggested. However, follow-up with repeat x-rays may be necessary. Some types of enchondromas can develop into malignant, or cancerous, bone tumors later. Careful follow-up with a physician may be recommended.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "Bone tumors". Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 3 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. p. 338. ISBN 978-92-832-4503-2.

- ^ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Suster, David; Hung, Yin Pun; Nielsen, G. Petur (1 January 2020). "Differential Diagnosis of Cartilaginous Lesions of Bone". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 144 (1): 71–82. doi:10.5858/arpa.2019-0441-RA. ISSN 0003-9985. PMID 31877083.

- ^ a b c d e f WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "Enchondroma". Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 3 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. pp. 353–355. ISBN 978-92-832-4503-2.

- ^ Engel, Hannes; Herget, Georg W.; Füllgraf, Hannah; Sutter, Reto; Benndorf, Matthias; Bamberg, Fabian; Jungmann, Pia M. (March 2021). "Chondrogenic Bone Tumors: The Importance of Imaging Characteristics". RöFo: Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Röntgenstrahlen und der Nuklearmedizin. 193 (3): 262–275. doi:10.1055/a-1288-1209. ISSN 1438-9010. PMID 33152784.

- ^ Pal, Julie; Wallman, Jackie (2019). "33. Ganglions and tumours of the hands and wrist". In Wietlisbach, Christine M. (ed.). Cooper'sFundamentals of Hand Therapy E-Book: Clinical Reasoning and Treatment Guidelines for Common Diagnoses of the Upper Extremity. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-323-52479-7.

- ^ Wang XL, De Beuckeleer LH, De Schepper AM, Van Marck E (2001). "Low-grade chondrosarcoma vs enchondroma: challenges in diagnosis and management". European Radiology. 11 (6): 1054–1057. doi:10.1007/s003300000651. PMID 11419152. S2CID 34059862.

External links

[edit]- Enchondroma Radiology