Ferdinand Lee Barnett (Chicago)

Ferdinand Lee Barnett | |

|---|---|

Barnett in 1900 | |

| Born | February 18, 1852 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | March 11, 1936 (aged 84) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Woods Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Union College of Law |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations | Republican |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 6, including Alfreda |

| Relatives | Ferdinand L. Barnett and Alfred S. Barnett (cousins) |

Ferdinand Lee Barnett (February 18, 1852 – March 11, 1936) was an American journalist, lawyer, and civil rights activist in Chicago, beginning in the late Reconstruction era.

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, during his childhood, his African-American family fled to Windsor, Ontario, Canada, just before the American Civil War. After the war, they settled in Chicago, where Barnett graduated from high school, and then obtained his law degree from what is today Northwestern University School of Law. He was a founding editor of the African-American oriented The Chicago Conservator monthly in 1878. The third black person to be admitted to the practice of law in Illinois, he also became a successful lawyer.[1]

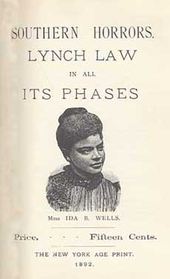

In 1895, Barnett married Ida B. Wells, a fellow journalist and anti-lynching activist. In 1896, he became Illinois' first black assistant state's attorney. He was active in anti-lynching and civil rights causes and was called "one of the foremost citizens Chicago has ever had" by the Chicago Defender.[2]

Early life

[edit]Ferdinand Lee Barnett was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1852.[2] His mother was a freewoman,[3] Martha Brooks, born about 1825. His father, also named Ferdinand Lee Barnett, was born in Nashville about 1810 and worked as a blacksmith. He purchased his family's freedom the year Ferdinand was born. They lived in Nashville until about 1859, when they left the United States and moved to Windsor, Ontario, across the Detroit River from Detroit, Michigan.[4] They wanted to avoid the reach of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which had created incentives for slave catchers to kidnap free blacks and sell them into slavery.

The Barnett family returned to the US in 1869 after the American Civil War and the end of slavery, settling in Chicago, Illinois. Ferdinand was educated in Chicago schools,[2] first attending the old Jones school at Clark and Harrison. He entered Central High School,[3] graduating in 1874. After high school, he taught in the southern United States for two years before returning to Chicago to attend Union College of Law, now Northwestern Law School. Barnett graduated from law school and was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1878.[2] He was the third black person to pass the Illinois bar, following Lloyd G. Wheeler and Richard A. Dawson.[5]

Numbered among his cousins were Ferdinand L. Barnett and his brother Alfred S. Barnett. They were also journalists and lived in Omaha, Nebraska, and Des Moines, Iowa, respectively.[6]

Barnett's father died in early February 1898.[7] His mother died on November 11, 1908.[8]

Conservator and early activism

[edit]In December 1877, Barnett, along with co-editors Abram T. Hall, Jr. and James E. Henderson, organized the semi-monthly newspaper, the Conservator, the first edition appearing on January 1, 1878.[9] Also among the editors and stakeholders was Iowan Alexander Clark.[10] He moved to Chicago in 1884, where he served as an editor of the paper. (Clark was appointed as US ambassador to Liberia in 1891.)[11]

The Conservator was a radical journal that focused on justice and equal rights, and Barnett was soon recognized as a local black leader. He was selected as a delegate to the May 1879 National Conference of Colored Men in Nashville, where he gave a noted speech calling for unity and education.[2] He was a delegate to the 1884 Inter-State Conference of Colored Men in Pittsburgh,[12] and the national convention of the Timothy Thomas Fortune led Afro-American League in Chicago in 1890 where he was named secretary.[13]

Legal and political career

[edit]Barnett started practicing law around 1883.[2] His prominence grew quickly and in 1888 he was considered for a Republican nomination for Cook County Commissioner.[14] In 1892, he started a law partnership with S. Laing Williams. The pair split over Williams' affiliation with Booker T. Washington, whom Barnett frequently opposed.[2]

Ida B. Wells

[edit]

In 1892, three men, including a friend of Ida B. Wells, were lynched by a white mob while in police custody in Memphis, Tennessee, in an event known as the Peoples Grocery lynching. The act sparked a national outcry and Barnett took part in meetings in Chicago called to organize reaction. At a meeting of one thousand people at Bethel A. M. E. Church, Reverend W. Gaines' call for the crowd to sing the then de facto national anthem, "My Country, 'Tis of Thee", was refused, one member of the audience declaring: "I don't want to sing that song until this country is what it claims to be, 'sweet land of liberty'."[15] Gaines substituted the Civil War-era song about the abolitionist martyr, "John Brown's Body". Barnett closed the meeting appealing for a calm and careful response, but also expressing great frustration and concern that the violence against blacks may one day lead to reprisals.[15][16]

The event inspired Wells, who began to research and speak out against lynchings. In 1893, Wells sued the Memphis Commercial for libel when the journal attacked Wells over her reports on the racism and injustice of lynching. It had been claimed that lynching, while not legal, was a natural result of the need for revenge of a community against perpetrators of violent crime and did not single out blacks. Wells' work showed the falseness of this narrative. Wells asked lawyer and activist Albion W. Tourgee to represent her on the case, but Tourgee refused, having largely retired from law (with the exception of his ongoing support of the case which would become Plessy v Fergusson). Tourgee recommended Wells contact Barnett, and Barnett agreed to take the case. This may have been Barnett's introduction to Wells, whom he would marry two years later. However, Barnett came to agree with the advice of Tourgee that the case could not be won, as a black woman would never win such a case heard by a white, male jury, and the case was dropped.[17]

World's Fair

[edit]In 1893, Barnett coauthored a pamphlet entitled "The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World's Columbian Exposition – The Afro-American's Contribution to Columbian Literature". The exposition, held in Chicago, refused to include an African-American exhibit. The pamphlet was another early example of Barnett's personal and professional relationship with Wells.[2] The pamphlet was published by Barnett, Wells, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and educator Irvine Garland Penn. The exhibition included many exhibits put on by individuals and approved by white organizers of the fair, including exhibits by the sculptor Edmonia Lewis, a painting exhibit by scientist George Washington Carver and a statistical exhibit by John Imogen Howard. It also included blacks in white exhibits, such as Nancy Green's portrayal of the character "Aunt Jemima" for the R. T. Davis Milling Company.[18]

Marriages and family

[edit]

Barnett's first wife, Mary Henrietta Graham Barnett, was the first black woman to graduate from the University of Michigan in 1876.[20][21] Mary and Ferdinand had two children, Ferdinand Lee and Albert Graham Barnett. Mary died in 1890[2] of heart disease.[22] The younger Ferdinand Barnett served as Eighth Regiment supply sergeant in World War I.[19] Albert Barnett became the city editor of the Defender in Chicago.[23]

Wells remained in Chicago after the Columbian Exposition. In June 1895, she and Barnett married. The couple had four children, Charles Aked (1896), Herman Kohlsaat (1897), Ida B. (1901), and Alfreda M. Barnett (later Alfreda Duster) (1904). Charles was named for the English anti-lynching activist Charles Aked, and Herman was named for the owner of the Chicago Inter Ocean, Herman Kohlsaat, who supported the Conservator.[2] Barnett's attraction to Wells included his recognition of the mutual support for each other's careers that the relationship would bring. Shortly before their marriage, Wells purchased Barnett's stake in the Conservator and became the paper's manager and co-editor, while Barnett focused on his legal career.[21] Reverend Richard DeBaptiste, founder of Olivet Baptist Church, was co-editor after Barnett.[24]

Later career

[edit]

Barnett was an active Republican, and his support for the party put him in line for public office. In 1896, he was put in charge of the bureau of information and education for blacks by the Republican National Committee.[25]

Also in 1896, Barnett became the first black assistant state's attorney in Illinois; he was appointed by Cook County State's Attorney Charles S. Deneen on the recommendation of the Cook County Commissioner Edward H. Wright.[2] As assistant state's attorney, Barnett worked in the juvenile court, in antitrust cases, and in habeas corpus and extradition proceedings. He frequently appeared before the Illinois Supreme Court and had a good record.[2] In 1902, Barnett made national news when he suggested that 10 million blacks would revolt against lynch law in the South at a gathering at Bethlehem Church in Chicago.[26] In 1904 he was appointed as head of the Chicago branch of the Republican Party's Negro Bureau. This appointment was opposed by Booker T. Washington, who preferred Barnett's former partner, S. Laing Williams.[2]

Municipal court judgeship controversy

[edit]In 1906, Barnett was nominated as a judge in the new Municipal Court of Chicago, the first black candidate for a judgeship in Illinois. Barnett lost the election by 304 votes due to a lack of support by white[2] and black Republicans. In the campaign for the position, Barnett did not gain the full support of black ministers, particularly Archibald J. Cary. They were angry that his wife Ida B. Wells supported gambling kingpin Bob Motts's Pekin Theatre – which was converted from a saloon. Barnett was initially declared winner, but the results were reviewed and Barnett became the only one of 27 Republican candidates rejected.[28] If he had been elected, Barnett would have been the second black judge in a court of record after Robert Heberton Terrell of Washington, D.C.[3]

Return to private practice and death

[edit]

Barnett left the position of assistant state's attorney in 1910, turning to private practice where he advocated for African-American rights. He often worked pro bono, focusing on employment discrimination and criminal cases.[2] In 1917, he was a candidate for alderman of the second ward in Chicago.[29] His most best remembered case was the defense with attorneys Robert M. McMurdy and Cowen of "Chicken Joe" Campbell. Although Campbell was convicted for the murder of Odelle B. Allen, his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by Governor Frank O. Lowden on April 12, 1918.[27]

In the 1920s, Barnett and his wife supported Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association.[28] In the 1920s and 1930s, Barnett began to support the Democratic Party.[2]

Barnett died aged 84 on March 11, 1936.[2] He was buried alongside Ida B. Wells at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

References

[edit]- ^ Lupton, John A. (February 24, 2020). "Illinois Supreme Court History: Ferdinand Barnett". illinoiscourts.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Finkelman, Paul, ed. Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, 2009. pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b c "Negro Elected to Judgeship", San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, California) December 17, 1906, p. 3. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ "Golden Wedding of Colored Couple", Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, Illinois), June 28, 1897, p. 5. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ McCaul, Robert L. The Black Struggle for Public Schooling in Nineteenth-Century Illinois. SIU Press, 2009, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Alfreda Duster (1904–1983), Chicago, Illinois. Interviewed by: Marcia McAdoo Greenlee, March 8 and 9, 1978. Library, Harvard University, p. 20. Accessed March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Death of F. L. Barnett St", The Appeal (Saint Paul, Minnesota), February 5, 1898, p. 4. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ [No Headline] The New York Age (New York, New York), November 19, 1908, p. 5. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ [No Headline] Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) December 10, 1877, p. 9. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- ^ Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p1100

- ^ Connie Street, "Black history pioneer: Alexander Clark became prominent achiever while residing in Muscatine", Muscatine Journal, 24 February 2006.

- ^ The Colored Men, Detroit Free Press (Detroit, Michigan), April 30, 1884, p. 2. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- ^ "Afro-Americans", The Ottawa Daily Republic (Ottawa, Kansas), January 16, 1890, p. 1. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- ^ [No Headline], The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), September 12, 1888, p. 4. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Wouldn't Sing America", The Evening World (New York, New York), March 28, 1892, p. 3. Accessed September 16, 2016,

- ^ "Not Their Country", The Decatur Herald (Decatur, Illinois), March 29, 1892, p. 1. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ Karcher, Carolyn L. A Refugee from His Race: Albion W. Tourgée and His Fight Against White Supremacy. UNC Press Books, 2016.

- ^ See introduction of the 2013 edition of Rydell, Robert W. All the world's a Fair: Visions of Empire at American international expositions, 1876–1916. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

- ^ a b "Breaking Home Ties", The Broad Ax (Salt Lake City, Utah), December 22, 1917, p. 14. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ "Pretty Good, Man", The University Record, September 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Bay, Mia. To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells. Macmillan, 2009.

- ^ Bradwell, James B, "The Colored Bar of Chicago", Chicago Legal News (Chicago, Illinois), Vol. XXIX, No. 10, October 31, 1896.

- ^ [No Headline], The Pittsburgh Courier (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), December 3, 1932, p. 17. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ Dolinar, Brian, ed. The Negro in Illinois: The WPA Papers. University of Illinois Press, 2013, p. 113.

- ^ "Allison Says Iowa is Safe", The New York Times, August 18, 1896, p. 3. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- ^ "Colored Race's Rights", Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City, Utah) May 23, 1902, p. 3. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Chicken Joe Campbell will not Hand for Governor Frank O Lowden has Commuted his Death Sentence to Life Imprisonment", The Broad Ax (Salt Lake City, Utah), April 13, 1918, p. 3. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Reed, Christopher Robert. Knock at the Door of Opportunity: Black Migration to Chicago, 1900–1919. SIU Press, 2014, pp. 191, 289.

- ^ F. L. Barnett, "Candidate for Alderman", The Broad Ax (Salt Lake City, Utah), February 24, 1917, p. 4. Accessed September 16, 2016.