Ficus Ruminalis

The Ficus Ruminalis was a wild fig tree that had religious and mythological significance in ancient Rome. It stood near the small cave known as the Lupercal at the foot of the Palatine Hill and was the spot where according to tradition the floating makeshift cradle of Romulus and Remus landed on the banks of the Tiber. There they were nurtured by the she-wolf and discovered by Faustulus.[1][2] The tree was sacred to Rumina, one of the birth and childhood deities, who protected breastfeeding in humans and animals.[3] St. Augustine mentions a Jupiter Ruminus.[4]

Name

[edit]The wild fig tree was thought to be the male, wild counterpart of the cultivated fig, which was female. In some Roman sources, the wild fig is caprificus, literally "goat fig". The fruit of the fig tree is pendulous, and the tree exudes a milky sap if cut. Rumina and Ruminalis ("of Rumina") were connected by some Romans to rumis or ruma, "teat, breast," but some modern linguists think it is more likely related to the names Roma and Romulus, which may be based on rumon, perhaps a word for "river" or an archaic name for the Tiber.[5]

Legend

[edit]The tree is associated with the legend of Romulus and Remus, and stood where their cradle came to rest on the banks of the Tiber, after their abandonment. It was thought to be located in the Velabrum, a short distance from the Lupercal. The tree offered the twins shade and shelter in their suckling by a she-wolf, just outside the nearby Lupercal cave, until their discovery and fostering by the shepherd Faustulus and his wife Acca Larentia. Remus was eventually killed by Romulus, who went on to found Rome on the Palatine Hill, above the cave.[6][7]

History

[edit]

A statue of the she-wolf was supposed to have stood next to the Ficus Ruminalis. In 296 BC, the curule aediles Gnaeus and Quintus Ogulnius placed images of Romulus and Remus as babies suckling under her teats.[8] It may be this sculpture group that is represented on coins.[9]

The Augustan historian Livy says that the tree still stood in his day,[10] but his younger contemporary Ovid observes only vestigia, "traces,"[11] perhaps the stump.[12] A textually problematic passage in Pliny[13] seems to suggest that the tree was miraculously transplanted by the augur Attus Navius to the Comitium. This fig tree, however, was the Ficus Navia, so called for the augur. Tacitus refers to the Ficus Navia as the Arbor Ruminalis, an identification that suggests it had replaced the original Ficus Ruminalis, either symbolically after the older tree's demise, or literally, having been cultivated as an offshoot. The Ficus Navia grew from a spot that had been struck by lightning and was thus regarded as sacred.[14] Pliny's obscure reference may be to the statue of Attus Navius in front of the Curia Hostilia:[15] he stood with his lituus raised in an attitude that connected the Ficus Navia and the accompanying representation of the she-wolf to the Ficus Ruminalis, "as if" the tree had crossed from one space to the other.[16] When the Ficus Navia drooped, it was taken as a bad omen for Rome. When it died, it was replaced.[17] In 58 AD, it withered, but then revived and put forth new shoots.[18]

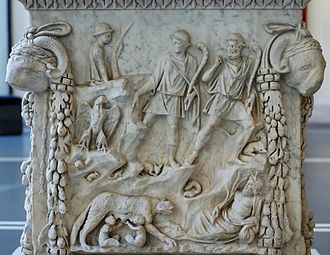

In the archaeology of the Comitium, several irregular stone-lined shafts in rows, dating from Republican phases of pavement, may have been apertures to preserve venerable trees during rebuilding programs. Pliny mentions other sacred trees in the Roman Forum, with two additional figs. One fig was removed with a great deal of ritual fuss because its roots had undermined a statue of Silvanus. A relief on the Plutei of Trajan depicts Marsyas the satyr, whose statue stood in the Comitium, next to a fig tree that is placed on a plinth, as if it too were a sculpture. It is unclear whether this representation means that sacred trees might be replaced with artificial or pictorial ones. The apertures were paved over in the time of Augustus, an event that may explain Ovid's vestigia.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Livy, I.4

- ^ Varro, De lingua latina 5.54; Pliny, Natural History 15.77; Plutarch, Life of Romulus 4.1; Servius, note to Aeneid 8.90; Festus 332–333 (edition of Lindsay).

- ^ Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), p. 151.

- ^ Augustine, De Civitate Dei 7.11, as cited by Arthur Bernard Cook, "The European Sky-God, III: The Italians," Folklore 16.3 (1905), p. 301.

- ^ Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 151.

- ^ Livy, I.4

- ^ Varro, De lingua latina 5.54; Pliny, Natural History 15.77; Plutarch, Life of Romulus 4.1; Servius, note to Aeneid 8.90; Festus 332–333 (edition of Lindsay).

- ^ Livy 10.23.12; Dionysius of Halicarnassus 1.79.8.

- ^ Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 151.

- ^ Livy 1.4: ubi nunc ficus Ruminalis est.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti 2.411.

- ^ Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 151.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 15.77.

- ^ Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, p. 150.

- ^ Festus 168–170 (Lindsay); Dionysius of Halicarnassus 3.71.5.

- ^ Richardson, Topographical Dictionary, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 15.77.

- ^ Tacitus, Annales 13.58.

- ^ Rabun Taylor, "Roman Oscilla: An Assessment," in RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 48 (2005), pp. 91–92. Taylor conjectures that oscilla were hung from such trees.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Ficus Ruminalis. In: Samuel Ball Platner, Thomas Ashby: A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press, London 1929. (online, LacusCurtius)