HERC1

| HERC1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | HERC1, p532, p619, HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase family member 1, MDFPMR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 605109; MGI: 2384589; HomoloGene: 31207; GeneCards: HERC1; OMA:HERC1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase HERC1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the HERC1 gene.[5][6][7]

The protein encoded by this gene stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on ARF1 and Rab proteins. This protein is thought to be involved in membrane transport processes[7]

Knowledge of the gene is facilitated by the discovery of a mouse mutation. The tambaleante (tbl) mutation arose spontaneously on the DW/J-Pas genetic background,[8] a recessive mutation of the Herc1 gene located on mouse chromosome 9 that increases Herc1 protein levels.[9] This protein is largely expressed in many tissues (Sanchez-Tena et al., 2016; https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000103657-HERC1/tissue) and multiple brain regions including the cerebellum (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000103657-HERC1/brain).

Herc1-tbl (tambaleante) mutant mice are characterized by Purkinje cell loss.[8] In addition to the cerebellum, Herc1tbl mutants had lower dendritic spine widths in CA1 pyramidal neurons.[10] Herc1-tbl mutant mice are also characterized by cerebellar ataxia, an unstable gait, and a limb-flexion reflex triggered by tail lifting[9] seen in other cerebellar mutants, the reverse of the normal limb extensor reflex.[11]

Relative to wild-type mice, Herc1-tbl mutant mice fell sooner and more often from a rotarod,[12][13] fell sooner from a vertical pole,[14][9] slipped more often and took more time to reach the end of a stationary beam,[13] and had weaker forelimb grip strength measured by a grip strength meter.[12] The rotarod deficit was rescued when Herc1tbl mutants were bred with transgenic mice expressing normal human HERC1.[9] Herc1tbl mutants were also less adept at landing correctly on all four legs when released in the air.[14]

Biallelic HERC1 mutations were reported in two siblings with facial dysmorphism, macrocephaly, motor development delay, ataxic gait, hypotonia, and intellectual disability.[15] Likewise, a nonsense HERC1 variant was reported in one subject with an autosomal recessive condition consisting of facial dysmorphism, macrocephaly, epilepsy, motor development delay, cerebellar atrophy, and intellectual disability.[16] Facial dysmorphism, macrocephaly, and intellectual disability but without cerebellar ataxia were also reported in two siblings with a HERC1 splice variant mutation.[17] The lack of cerebellar involvement was ascribed either to the nature of the mutation or the influence of modifier genes. Another patient with a frameshift HERC1 mutation predicted to truncate the protein displayed facial dysmorphism, macrocephaly, epileptiform discharges, hypotonia, intellectual disability, and autistic features.[18]

Notes

[edit]

The 2022 version of this article was updated by an external expert under a dual publication model. The corresponding academic peer reviewed article was published in Gene and can be cited as: Robert Lalonde; Catherine Strazielle (10 March 2022). "The Herc1 gene in neurobiology". Gene. Gene Wiki Review Series. 814. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2021.146144. ISSN 0378-1119. PMID 34990797. Wikidata Q110874820. |

References

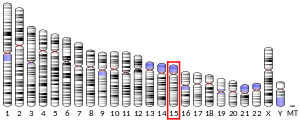

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000103657 – Ensembl, May 2017

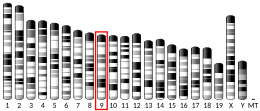

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000038664 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Rosa JL, Casaroli-Marano RP, Buckler AJ, Vilaro S, Barbacid M (Dec 1996). "p619, a giant protein related to the chromosome condensation regulator RCC1, stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on ARF1 and Rab proteins". EMBO J. 15 (16): 4262–73. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00801.x. PMC 452152. PMID 8861955.

- ^ Rosa JL, Barbacid M (Aug 1997). "A giant protein that stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on ARF1 and Rab proteins forms a cytosolic ternary complex with clathrin and Hsp70". Oncogene. 15 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201170. PMID 9233772.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: HERC1 hect (homologous to the E6-AP (UBE3A) carboxyl terminus) domain and RCC1 (CHC1)-like domain (RLD) 1".

- ^ a b Wassef M, Sotelo C, Cholley B, Brehier A, Thomasset M (Dec 1996). "Cerebellar mutations affecting the postnatal survival of Purkinje cells in the mouse disclose a longitudinal pattern of differentially sensitive cells". Dev Biol. 124 (2): 379–89. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(87)90490-8. PMID 3678603.

- ^ a b c d Mashimo T, Hadjebi O, Amair-Pinedo F, Tsurumi T, Langa F, Serikawa T, Sotelo C, Guénet JL, Rosa JL (2009). "Progressive Purkinje cell degeneration in tambaleante mutant mice is a consequence of a missense mutation in HERC1 E3 ubiquitin ligase". PLOS Genet. 5 (2): e1000784. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000784. PMC 2791161. PMID 20041218.

- ^ Pérez-Villegas EM, Pérez-Rodríguez M, Negrete-Díaz JV, Ruiz R, Rosa JL, de Toledo GA, Rodríguez-Moreno A, Armengol JA (2020). "HERC1 Ubiquitin ligase is required for hippocampal learning and memory". Front Neuroanat. 14: 592797. doi:10.3389/fnana.2020.592797. PMC 7710975. PMID 33328904.

- ^ Lalonde R, Strazielle C (2011). "Brain regions and genes affecting limb-clasping responses". Brain Res Rev. 67 (1–2): 252–9. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2011.02.005. PMID 21356243. S2CID 206345554.

- ^ a b Bachiller S, Rybkina T, Porras-García E, Pérez-Villegas E, Tabares L, Armengol JA, Carrión AM, Ruiz R (2015). "The HERC1 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase is essential for normal development and for neurotransmission at the mouse neuromuscular junction". Life Sci. 72 (15): 2961–71. doi:10.1007/s00018-015-1878-2. PMC 11113414. PMID 25746226. S2CID 1976227.

- ^ a b Fuca E, Guglielmotto M, Boda E, Rossi F, Leto K, Buffo A (2017). "Preventive motor training but not progenitor grafting ameliorates cerebellar ataxia and deregulated autophagy in tambaleante mice". Neurobiol Dis. 102: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2017.02.005. PMC 452152. PMID 28237314.

- ^ a b Porras-Garcia ME, Ruiz R, Pérez-Villegas EM, Armengol JÁ (2013). "Motor learning of mice lacking cerebellar Purkinje cells". Front Neuroanat. 7: 4. doi:10.3389/fnana.2013.00004. PMC 452152. PMID 23630472.

- ^ Ortega-Recalde O, Beltrán OI, Gálvez JM, Palma-Montero A, Restrepo CM, Mateus HE, Laissue P (2015). "Biallelic HERC1 mutations in a syndromic form of overgrowth and intellectual disability". Clin Genet. 88 (4): e1-3. doi:10.1111/cge.12634. PMID 26138117. S2CID 5725254.

- ^ Nguyen LS, Schneider T, Rio M, Moutton S, Siquier-Pernet K, Verny F, Boddaert N, Desguerre I, Munich A, Rosa JL, Cormier-Daire V, Colleaux L (2016). "A nonsense variant in HERC1 is associated with intellectual disability, megalencephaly, thick corpus callosum and cerebellar atrophy". Eur J Hum Genet. 24 (3): 455–8. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.140. PMC 4755376. PMID 26153217.

- ^ Aggarwal S, Bhowmik AD, Ramprasad, VL, Murugan S, Dalal A (2016). "A splice site mutation in HERC1 leads to syndromic intellectual disability with macrocephaly and facial dysmorphism: Further delineation of the phenotypic spectrum". Am J Med Genet A. 15 (16): 4262–73. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.37654. PMID 27108999. S2CID 44849688.

- ^ Utine GE, Taşkıran EZ, Koşukcu C, Karaosmanoğlu B, Güleray N, Doğan ÖA, Kiper PÖ, Boduroğlu K, Alikaşifoğlu M (2017). "HERC1 mutations in idiopathic intellectual disability". Eur J Med Genet. 60 (5): 279–83. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.03.007. PMID 28323226.

Further reading

[edit]- Ewing RM, Chu P, Elisma F, et al. (2007). "Large-scale mapping of human protein–protein interactions by mass spectrometry". Mol. Syst. Biol. 3 (1): 89. doi:10.1038/msb4100134. PMC 1847948. PMID 17353931.

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, et al. (2006). "Diversification of transcriptional modulation: Large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes". Genome Res. 16 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- Garcia-Gonzalo FR, Bartrons R, Ventura F, Rosa JL (2005). "Requirement of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate for HERC1-mediated guanine nucleotide release from ARF proteins". FEBS Lett. 579 (2): 343–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.095. PMID 15642342.

- Garcia-Gonzalo FR, Muñoz P, González E, et al. (2004). "The giant protein HERC1 is recruited to aluminum fluoride-induced actin-rich surface protrusions in HeLa cells". FEBS Lett. 559 (1–3): 77–83. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00030-4. PMID 14960311.

- Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, et al. (2004). "Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs". Nat. Genet. 36 (1): 40–5. doi:10.1038/ng1285. PMID 14702039.

- Garcia-Gonzalo FR, Cruz C, Muñoz P, et al. (2003). "Interaction between HERC1 and M2-type pyruvate kinase". FEBS Lett. 539 (1–3): 78–84. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00205-9. PMID 12650930. S2CID 32809019.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

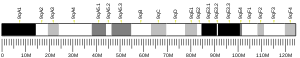

- Cruz C, Paladugu A, Ventura F, et al. (1999). "Assignment of the human P532 gene (HERC1) to chromosome 15q22 by fluorescence in situ hybridization". Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 86 (1): 68–9. doi:10.1159/000015414. PMID 10516438. S2CID 46241923.

- Ji Y, Walkowicz MJ, Buiting K, et al. (1999). "The ancestral gene for transcribed, low-copy repeats in the Prader-Willi/Angelman region encodes a large protein implicated in protein trafficking, which is deficient in mice with neuromuscular and spermiogenic abnormalities". Hum. Mol. Genet. 8 (3): 533–42. doi:10.1093/hmg/8.3.533. PMID 9949213.

- Yu W, Andersson B, Worley KC, et al. (1997). "Large-Scale Concatenation cDNA Sequencing". Genome Res. 7 (4): 353–8. doi:10.1101/gr.7.4.353. PMC 139146. PMID 9110174.

- Bonaldo MF, Lennon G, Soares MB (1997). "Normalization and subtraction: two approaches to facilitate gene discovery". Genome Res. 6 (9): 791–806. doi:10.1101/gr.6.9.791. PMID 8889548.

- Andersson B, Wentland MA, Ricafrente JY, et al. (1996). "A "double adaptor" method for improved shotgun library construction". Anal. Biochem. 236 (1): 107–13. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0138. PMID 8619474.