Haakon Lie

Haakon Lie | |

|---|---|

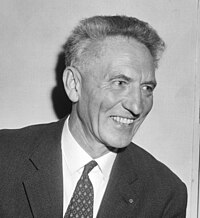

Haakon Lie in 1965 | |

| Born | Haakon Steen Lie 22 September 1905 |

| Died | 25 May 2009 (aged 103) |

| Occupation | Party secretary for the Norwegian Labour Party (1945–1969) |

| Spouse(s) | Ragnhild Gunderud (1929-1951) Minnie Dockermann (1952-1999) |

| Children | Gro (b. 1932) Turid (b. 1938) Karen (b. 1952) |

Haakon Steen Lie (22 September 1905 – 25 May 2009) was a Norwegian politician who served as party secretary for the Norwegian Labour Party from 1945 to 1969. Coming from humble origins, he became involved in the labour movement at an early age, and quickly rose in the party system. After actively working for the resistance movement and the exiled government during World War II, he was elected to the second-highest position in the party after the war, and his years in office were the most successful in the party's history.

Lie is widely considered – along with Einar Gerhardsen – to be the architect of the post-war success of the Labour Party, and of the Norwegian welfare state. At the same time, he has also been the subject of criticism for organising surveillance of Norwegian opposition figures, in particular communists. Lie remained active in Norwegian public life, even after his 100th birthday, and in 2008 he celebrated his 103rd birthday with the release of a new biography, "Slik jeg ser det nå" (As I see it now).

Early life and education

[edit]Born 22 September 1905 into a family of Finnish origin in Oslo (then named Kristiania), he was baptized Håkon Steen Lie. He would later change the spelling to Haakon during World War II.[1][2] His father was fireman Andreas Lie (1870-1942) and his mother was homemaker Karen Halvorsdatter Gunderud (1871-1952).[1] Though he describes his childhood as a happy one, his family was poor and, until 1916, his father had to work 120 hours a week.[3][4] With his parents, two brothers, and two sisters, he grew up at his fathers fire-station sharing one room and a kitchen in the St. Hanshaugen neighborhood.[5][6] Lie got involved with the labour movement at the age of sixteen, in 1921.[7]

Here he met some of his lifelong friends and colleagues: Martin Tranmæl, Oscar Torp, and Einar Gerhardsen. When the Labour Party left the Third Communist International in 1923, and was split between the new-founded Communist Party and the remaining social democrats, Lie ended up on the latter wing. The bitter strife between the two factions strongly influenced his lifelong anti-communist stance.[3]

Early career

[edit]After first attending Møllergata elementary school and later Ila elementary school, he graduated from Secondary school in 1925 and in 1927, after giving up university studies, (having attended the State School of Forestry in Kongsberg) and a brief stint as an industrial worker, he became a forester. He was happy with this occupation, but after a bout of tuberculosis in 1927, had to give it up as well,[3] and started working as secretary for the party. In 1931 he was made leader of Arbeidernes Opplysningsforbund (AOF, Workers' Information Society), an institution recently created to promote education in the working class.[3] Lie has cited the AOF as the proudest achievement of his career.[6]

In the early 1930s he made journeys to both Nazi Germany and Soviet Union. His experience with authoritarian states – both fascist and communist – helped reinforce his political outlook of a democracy/dictatorship dichotomy rather than a simple right/left one.[8] During the Spanish Civil War in 1936–39, he helped organise aid to those fighting the fascists and, during the winter of 1936–37, he visited the country.[8] At one point the former pacifist Lie also took flying lessons to actively participate in the conflict, but this plan was never carried out.[9]

World War II

[edit]When Norway was invaded by Germany in April 1940, Lie immediately started organising resistance, taking charge of free radio broadcasts from various locations in the country. For two months this work kept him in constant movement around Norway, and on 7 June 1940, when King Haakon VII and the government left the country for London, he was in Vadsø, replacing a broken transmitter.[8] At this point further broadcasts became impossible, and Lie had to make his way south, through Finland and Sweden, to Oslo.[6] Here he became involved in the underground labour movement, mainly through printing newspapers and spreading information.[8]

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the occupying authority in Norway started cracking down harder on opposition. A strike over milk rations in September led to the arrest and execution of the two labour leaders Viggo Hansteen and Rolf Wickstrøm.[8] This was followed by several high-profile arrests – among them Einar Gerhardsen – and Lie had to flee the country. He left his house only hours before the Germans appeared to arrest him.[8] From Sweden he made his way to the United Kingdom, where he worked as a propaganda secretary for the exiled Norwegian labour movement in London. He made two visits to the United States to gather support and financial aid, the first time he went from New York City to Seattle where he held a series of lectures and radio-interviews before he travelled through Canada from the west- to the east coast.[10] The second trip was as a labour attaché with diplomatic status.[8][11] While Haakon was in exile, his brother Per, who was also a labour activist, was arrested in Norway in 1942.[8] He was imprisoned and eventually sent to Dachau, where he died from typhoid fever in March 1945.[8][12]

Party secretary

[edit]On 20 June 1945, Lie returned to Norway. At the national convention of the Labour Party that same year, he was elected party secretary. While Gerhardsen became chairman and prime minister, and gradually assumed his role as "Father of the Nation" ("Landsfaderen"),[13] Lie maintained party discipline and staked out the political strategy in the background. From his position at the head of the party he helped orchestrate the predominant position the party was to hold in the following years, with absolute parliamentary majorities won in the 1945, 1949, 1953 and 1957 elections.[14] During the reconstruction of the post-war years, he helped lead the party onto a more moderate path. Private versus public ownership of industry now became a practical, rather than an ideological question. The policy proved highly successful; the country experienced unprecedented growth, as well as improved conditions for the working class, during his tenure.[14]

Anti-communist surveillance

[edit]Lie had been personally shaken by the post-war Soviet suppression of the social-democratic parties in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. He viewed Yugoslavia leader Josip Broz Tito as the "Martin Luther of communism" after Tito had openly defied the Soviet Union by chiselling out the Third Way. When the Soviets initiated a blockade of Yugoslavia following the Tito–Stalin split, Lie organized humanitarian aid-shipments from Norway. Another concern was that the Pro-Moscow Norwegian Communist Party (NKP) had was gaining support among leftist voters, with opinion polls showing an increase to 15.4%. As he put it :"It was voting based upon the myth of the Soviet Union as the land of peace and socialism - a myth which had to be broken down". It was during this period that Lie, with support from the trade union center set up significant and wide-ranging surveillance of Norwegian communists, (a practice later deemed illegal by a government committee, the Lund commission).[15]

Lie himself defended his hard-line tactics, claiming communism had represented a threat to democracy as well as the party, famously exclaiming "The Labour Party is no damn Sunday school! (Norwegian: Arbeiderpartiet er faen ingen søndagsskole!)". There were also external events that aided his cause. The Marshall Plan accepted in 1947 and the Norwegian membership in NATO from 1949 drew the nation closer to the United States. Meanwhile, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 demonstrated the threat represented by the Soviet Union.[14] Yet Lie was stronger in his support of the United States, and more fierce in his anti-communism, than most within the Labour party.

In 1961, a left-wing splinter group who was previously centred around the party newspaper "Orientering" decided to break off and form a new party known as Socialist People's Party (SF). They were later to deny the Labour Party a majority in the 1961 elections as well as to bring down the third cabinet Gerhardsen as a result of the Kings Bay Affair.[14]

Feud with Gerhardsen

[edit]Meanwhile, the relationship between Lie and Gerhardsen grew cooler. Gerhardsen was becoming far more amenable to the Soviets in part due to the influence of his wife, Werna, who was highly sympathetic to the Soviet Union (some even claiming she was a KGB informant).[14][16][17] Gerhardsen had grown more and more frustrated at Lie's hard-line tactics against communists and perceived Soviet sympathisers, as well as his attempts to stifle foreign policy debate within the Central Committee. Lie on his part grew embittered over what he perceived was the Gerhardsen-couple protecting key leftists, such as Trygve Bull. According to Bull, Lie and Gerhardsen hardly spoke to each other after 1957.

At the national party convention of 1967 Gerhardsen openly attacked Lie, to which Lie reportedly responded by threatening to "break" Gerhardsen "like a louse" ("Jeg skal knekke deg som en lus").[18] Gerhardsen later regretted the attack, and later sent Lie a letter of apology - to which the latter never replied. Lie resigned as party secretary in 1969, and Gerhardsen retired from active politics the same year.[11][19] It was not until 1985, at the behest of former defence minister Jens Christian Hauge, that the pair officially reconciled.

Later life

[edit]Lie remained active as a public commentator and in politics after his retirement from party politics, and even after his centenary.[9][20][21] He led the losing campaign for Norwegian membership in the EEC in the early 1970s,[11] and in 2000 he led a battle to prevent the privatisation of the national oil company Statoil.[22] His preferred method of staying updated on current international events was through weekly readings of The Economist.[6]

Influenced by the support he experienced from Jewish labour leaders in the United States, he was a supporter of the state of Israel,[23] though he is highly critical of the Israeli government's current treatment of the Palestinians and to the settlement of the West Bank.[4][24]

Lie initiated Operation donor funds for construction of Israeli settlement called "Moshav Norge" (Change to Yanuv) in memory of 28 children crashes in Hurum air disaster.

He wrote several books, among them the controversial memoir ...slik jeg ser det ("...the way I see it", 1975), in which he strongly attacked Gerhardsen. He also wrote a two-volume biography of his mentor Martin Tranmæl, Et bål av vilje and Veiviseren ("A Beacon of Resolve", 1988 and "The Pathfinder", 1991).[11] In his latest book, released in 2008 at 103 years of age, being traditionally a strong proponent of cooperation with the United States, he called for enhanced security cooperation between the Nordic countries and argued Norway should buy the Swedish JAS Gripen aircraft instead of the US-made Joint Strike Fighter.

In 1970, after retiring as party secretary, he acquired a patch of woodland where he could resume his passion for forestry.[6] For many years he spent his winters in the US state of Florida, but eventually moved back permanently to Norway.[4]

Lie died on 25 May 2009, aged 103, after a long illness. He had been hospitalised six months earlier.[25] Friends of Israel in the Norwegian Labour Movement (Norwegian: Venner av Israel i Norsk Arbeiderbevegelse), planted a forest to his memory in Israel.

Personal life

[edit]Lie was married twice – first in 1929 to Ragnhild Halvorsen (1905-91) a companion from the labour youth movement. They divorced in 1951 because when he was in America he met Minnie Dockterman, who would be his future wife, thereby creating a scandal. He married Minnie Dockterman in 1952 (1912–99).[1] He left three daughters, two; Gro (1932-) and Turid (1938-) by his first wife and one; Karen (1952) by the second wife.[24] In addition he left five grandchildren as well as six great-grandchildren.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Harboe & Lahlum 2009, p. 5.

- ^ The Oslo Agreement in Norwegian Foreign Policy pdf accessed 25.5.2009

- ^ a b c d Stein Bjørlo (2005). "Et bål av vilje: Haakon Lie - et portrett (page 1)" (in Norwegian). Labour Movement Archive and Library. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ a b c Halvor Hegtun (3 September 2005). "Hele folket foran TV'n". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Harboe & Lahlum 2009, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e Tore Gjerstad (10 September 2005). "Norges mektigste politiker? Bare sprøyt!". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Reidar Spigseth (27 June 2007). "Haakon Lie (101) forteller alt". Dagsavisen (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stein Bjørlo (2005). "Et bål av vilje: Haakon Lie - et portrett (page 2)" (in Norwegian). Labour Movement Archive and Library. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ a b Sigrun Slapgard (13 December 2007). "- Livsfarlig omlegging av forsvaret" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ Harboe & Lahlum 2009, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d "Lie, Haakon" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Labour Party. 22 May 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Ording, Arne; Johnson, Gudrun; Garder, Johan (1950). Våre falne 1939-1945 (in Norwegian). Vol. 3. Oslo: Grøndahl. p. 153.

- ^ Bjørn Talen (9 May 1987). "Gratulerer, kjære landsmann!". Aftenposten. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Stein Bjørlo (2005). "Et bål av vilje: Haakon Lie - et portrett (page 3)". Labour Movement Archive and Library. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Lund-rapporten" (in Norwegian). Government.no. 28 March 1996. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Jentoft, Morten. "Hevder kona fikk Gerhardsen til å endre syn på Sovjetunionen". NRK. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Meland, Astrid. "Sjarmert til spionasje". Dagbladet. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Trygve Monsen (22 October 2002). "Gerhardsen angret utfallet mot Haakon Lie". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ "Gerhardsen, Einar" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Labour Party. 23 November 2005. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Camilla Ryste (9 March 2007). "Haakon Lie: - Den beste løsningen". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Hilde Harbo (15 March 2008). "Haakon Lie (102) har fremdeles makt i Ap". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "Statoil-striden: Berntsen kan vurdere kompromiss". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). 25 June 2000. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Erling Bø (14 May 1998). "Drømmen om Israel". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ a b Stein Bjørlo (2005). "Et bål av vilje: Haakon Lie - et portrett (page 4)" (in Norwegian). Labour Movement Archive and Library. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Geir Arne Kippernes, Marianne Vikås og Hanne Hattrem (25 May 2009). "Haakon Lie er død". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). Retrieved 25 May 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Harboe, Hilde; Lahlum, Hans Olav (2009). Haakon Lie: Slik jeg ser det nå. Cappelen Damm.