Brutalism in Sheffield

1: Lansdowne

2: Hanover House

3: Netherthorpe Brook Hill

4: Upperthorpe

5: Callow Mount

6: Gleadless Valley

The 1950s and 1960s saw the construction of numerous brutalist apartment blocks in Sheffield, England. The Sheffield City Council had been clearing inner-city residential slums since the early 1900s.[1] Prior to the 1950s these slums were replaced with low-rise council housing, mostly constructed in new estates on the edge of the city.[1] By the mid-1950s the establishment of a green belt had led to a shortage of available land on the edges of the city, whilst the government increased subsidies for the construction of high-rise apartment towers on former slum land, so the council began to construct high-rise inner city estates, adopting modernist designs and industrialised construction techniques,[1] culminating in the construction of the award-winning Gleadless Valley and Park Hill estates.[2]

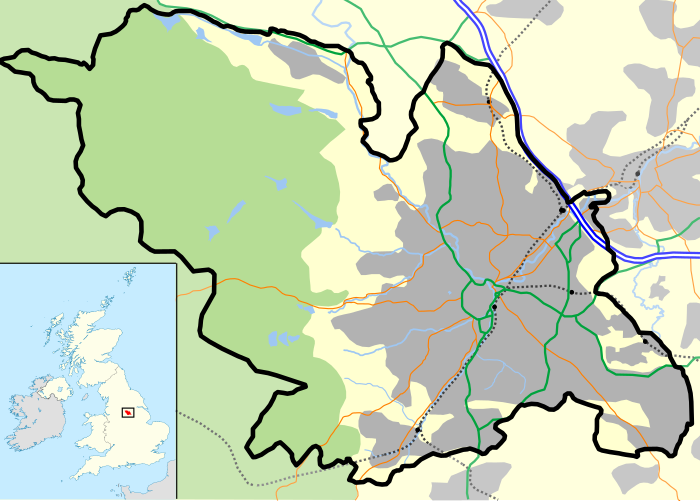

Map of major developments, 1955–1970

[edit]- As of 1 June 2020

- Key:

= Existing development

= Existing development = Partially existing development (some blocks demolished)

= Partially existing development (some blocks demolished) = Demolished development

= Demolished development- XX = Mouse over two-letter code for development name; click for link to section in this article.

Timeline of development

[edit]

Existing developments

[edit]Callow Mount

[edit]

Callow Mount, also known as Gleadless Valley (Rollestone), is a complex of six residential tower blocks that was completed in 1964, as part of the wider Gleadless Valley Redevelopment Area which also includes the Gleadless Valley and Herdings Twin Towers developments as well as a wide expanse of low-rise council housing. Callow Mount is located on the western side of the head of Blackstock Road at its junction with the B6388 Gleadless Road, opposite the Newfield Green shopping area towards the northern end of the Gleadless Valley development area. The Callow Mount complex was constructed by M J Gleeson on behalf of Sheffield City Council.[3]

One of the tower blocks at Callow Mount, named Callow, has fifteen floors containing 56 two-bedroom apartments, rising to a height of 41 m (135 ft). The remaining five towers, named Bankwood, Handbank, Newfield, Parkfield and Pemberton, each have thirteen floors, containing 48 one-bedroom apartments and rising to heights of 41 m (135 ft).[3] Each block consists of a non-residential ground floor, housing a laundry area and other communal facilities. Additionally, Callow houses the boiler rooms and other facilities for the district heating system which covers the entire Callow Mount complex in its ground floor and an adjacent single-story annexe; as a result, it differs visually from the other towers in having three metal chimneys attached to its northern facade.

The addresses of the six towers are as follows:

- Bankwood: 1–95 Callow Mount

- Callow: 1–111 Callow Place

- Handbank: 98–192 Callow Mount

- Newfield: 97–191 Callow Drive

- Parkfield: 1–95 Callow Drive

- Pemberton: 2–96 Callow Road

All six towers remain in operation as council housing directly operated by Sheffield City Council. However, Handbank is now reserved for residents over the State Pension age. A refurbishment project covering the entire complex was carried out in 2010–2011; as part of the project, the towers received new, predominantly green cladding. The design of the cladding additionally incorporates a uniquely coloured stripe in the facade of each face and around the rooftop to identify each building; Bankwood is light green, Callow is turquoise, Handbank is orange, Newfield is dark green, Parkfield is blue, and Pemberton is red. This colour scheme had already been in place around the doorways of each tower since construction, although the refurbishment made it much more prominent.

Gleadless Valley

[edit]

The Gleadless Valley project is an expansive complex of 36 six-storey tower blocks (of which 22 still exist) located throughout the wider Gleadless Valley Redevelopment Area, between the related Callow Mount and Herdings Twin Towers developments. The Gleadless Valley blocks were completed between 1955 and 1962[4] by a consortium consisting of H. Dernie Construction and direct municipal labour groups belonging to what was then the Sheffield County Borough Council.[5] The blocks of flats are located quite widely across the development area, with a ring of them lining the outer side of Blackstock Road (four blocks), Gaunt Road (13) and Ironside Road (11) while the inner sides and areas confined by these three roads are largely covered by low-rise housing. An additional row of eight largely identical blocks were constructed 0.25 mi (0.40 km) away on Raeburn Road, next to Herdings Park. Each block is largely identical inside, containing twelve dwellings for a total of 432 residencies across the complex as-built.[5]

This area of the Gleadless Valley, particularly along Blackstock Road, is very steeply-sloping on the western side of the valley of the Meers Brook. Indeed, Sheffield City Council had initially marked this area as unsuitable for development. Despite the Gleadless Valley already being within the borders of Sheffield, the council instead pursued the purchase of flatter land in neighbouring North East Derbyshire for development; when permission for this was rejected by the central government, the council instead began development of this section of the Gleadless Valley as a last resort. Incidentally, the area of rural Derbyshire initially earmarked for development would later be ceded to South Yorkshire and developed as the Mosborough Townships in the 1990s.

The steep terrain of the Gleadless Valley presented a considerable challenge for the development consortium to overcome, especially since the council were pushing for development of dense high-rise social housing. As a result, a unique design was used in the construction of most of these buildings, designed by city architect J. L. Womersley.[4] They are set back on average around 30 m (98 ft) from the side of the road, part way down the hillside; a flat bridge from road level leads directly into the third floor in the middle of the building, with staircases up to the upper floors and down to the lower floors. The only exception to this were seven of the eight Raeburn Road blocks, which were constructed on flat enough land to allow a conventional ground-level entrance and central staircase upwards to all six floors.

Following the completion of the Gleadless Valley development, which also included surrounding low-rise housing, the buildings were described as state-of-the-art and the jewel in the crown of the local council for their unusual construction.[4] During the 1960s and 1970s, the estate won many national and international awards; however, by the start of the 2000s, the area had become one of the most deprived areas of the city and within the 10% most deprived areas of the country.[4][6] The Gleadless Valley Tenants and Residents Association (GV-TARA) was founded in the 2010s to further the interests of the area.

The thirteen blocks of this style located alongside Gaunt Road, plus the sole Raeburn Road block that contained a bridge, were demolished between 2002 and 2005. As of June 2020, the sites of these buildings remain unoccupied. The other 22 blocks remain in use as council housing operated directly by Sheffield City Council. In September 2017, the council opened a consultation regarding the future of the estate. This resulted in the unveiling of a local master plan in late 2018, which received £500,000 in central government funding for the refurbishment of the Gleadless Valley blocks of flats in early 2019.[6]

Hanover House

[edit]

Hanover House (simply Hanover when first built) is a single block of flats located on Exeter Drive, just off the A61 Hanover Way dual-carriageway which nowadays is part of the Sheffield Inner Ring Road. Construction of Hanover House was carried out by M J Gleeson on behalf of the Sheffield City Council and commenced in 1965, completing in 1966. The single tower consists of 16 floors, all of them residential, containing a total of 126 residencies and rising to a height of 43 m (141 ft).[7] The flats within Hanover House are addressed 101–349 Exeter Drive.

Nine blocks of five-storey maisonette-style council housing were built on the roads surrounding Hanover House around the same time; additionally, the Hanover development was located a short distance from the now-demolished Broomhall complex on the opposite side of the inner ring road. The original exterior design of Hanover House consisted of exposed concrete accented with metal panes painted yellow. As part of a refurbishment of the tower, this was replaced in 2009 by green and grey plastic cladding covering the entire structure. The maisonettes surrounding Hanover House were refurbished around the same time, with external concrete panels being repainted blue, green, orange, red, maroon, lilac or terracotta to differentiate each block.

The design of retrofitted cladding was strongly implicated in the devastatingly rapid spread of the Grenfell Tower fire which killed 72 people in a similarly-designed tower block in London in June 2017. As a result, safety inspections were carried out on all tower blocks across the country which had been retrofitted with replacement cladding. The cladding applied to Hanover House was the only tower block cladding in Sheffield which failed fire safety tests, and it was subsequently confirmed by Sheffield City Council that it would be removed.[8] Removal of the cladding commenced in July 2017 and was completed by the end of the year. Replacement cladding, identical in visual design but now passing fire safety tests, was applied to the building from April 2019 onwards, restoring Hanover House to its pre-Grenfell appearance by the start of 2020.

Herdings Twin Towers

[edit]

The Herdings complex, also known as Gleadless Valley (Herdings), is located on Raeburn Place adjacent to Herdings Park at the southern end of the Gleadless Valley Redevelopment Area, which also included the Callow Mount and Gleadless Valley schemes. Construction of the Herdings towers commenced in 1958 and was completed in 1959. Construction was carried out by Tersons Ltd., who later became part of the British Insulated Callender's Cables company, on behalf of the Sheffield City Council.[9]

When built, there were three towers on this site, named Leighton, Morland and Raeburn and receiving the nickname The Three Sisters due to their prominent location on a hill overlooking the city. However, Raeburn had been constructed atop a fault line, undiscovered at the time of construction, which threatened the stability of the building. As a result, it was demolished using explosives on 13 October 1996.[10] Subsequently, the remaining buildings were newly nicknamed the Herdings Twin Towers. The site of Raeburn remained unoccupied for almost two decades, until low-rise private housing was constructed on the site and around the remaining twin towers between 2013 and 2015.

All three towers were 38 m (125 ft) tall, containing 48 single-bedroom flats across the upper twelve floors; the ground floor contains a laundry area and other communal facilities, taking the total floor count to thirteen. Morland was subsequently extended in height to 55 m (180 ft) by virtue of the placement of a rooftop radio antenna, becoming the second-tallest building in Sheffield when completed in 1959; as of June 2020, it is now the tenth-tallest, and the only remaining brutalist tower block in this article within the top 10.

The remaining twin towers were leased from the council to Places for People as private housing and subsequently refurbished in 1998, after suffering from decades of damp and draught problems due to poor construction. Leighton was renamed to Queen Elizabeth Court, receiving predominantly white cladding with green stripes; Morland was renamed to Queen Anne Court, receiving identical cladding with the exception of a blue stripe instead of green.

Hyde Park

[edit]

The Hyde Park flats, also known during construction as Park Hill (Part Two), were constructed on the site of cleared inner-city slums on the hillside immediately to the east of Sheffield City Centre. The area of slums which previously occupied this area had become one of the most deprived areas of the country by the 1930s, receiving the nickname Little Chicago due to its high rate of violent crime, until they were cleared before the start of World War II.

Following the success of the nearby Park Hill scheme, Hyde Park was constructed as an even more expansive 'streets in the sky' social housing concept. Plans were approved by the Sheffield City Council's Housing Committee at a meeting on 21 February 1958. The four Hyde Park blocks were designed by city architects J. L. Womersley (also involved in Park Hill and the expansive Gleadless Valley redevelopment), W. L. Clunie and A. V. Smith, and construction commenced in 1962 under direct municipal labour.[11] Construction was completed in 1966, and the flats were officially opened by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother on 23 June 1966.[12]

Four blocks of flats were built at Hyde Park, all in a similar streets in the sky style to Park Hill. The largest of the blocks, Block B, consisted of nineteen storeys containing 678 flats, rising to a height of 56 m (184 ft) and becoming the city's third-tallest building upon completion, behind only Sheffield Town Hall and the Arts Tower (which was opened by the Queen Mother earlier the same day as Block B). The remaining three blocks – A, C and D – were more modest in height, comparable to those at Park Hill, containing nine, ten and thirteen storeys and 28, 108 and 355 individual dwellings respectively.[11] When also including the low-rise maisonettes that were constructed in the Hyde Park area around the same time, the estate was capable of housing more than 4,600 people in 1,313 residencies.

Much of the Hyde Park estate fell into deprivation in the 1980s following the collapse of the local steel and coal industries and subsequent economic downturn and population flight from Sheffield. Blocks C and D were refurbished in 1990 in order to be used as the athletes village for the 1991 World Student Games, hosted by Sheffield. Following the conclusion of the games, they returned to use as council housing. The smallest and largest of the Hyde Park blocks, A and B respectively, were both demolished in 1992; they had not seen use during the games. Blocks C and D were subsequently leased out by the council to Places for People and refurbished in a similar manner to the Herdings Twin Towers in the late 1990s, receiving new names in the process – Harold Lambert Court for Block C and Castle Court for Block D. Both blocks were refurbished with predominantly white cladding covering their distinctive concrete structures, with red detailing on Castle Court and green detailing on Harold Lambert Court. The land formerly occupied by Blocks A and B was redeveloped as the Manor Oaks Gardens low-rise detached housing estate in the early 2000s.

Lansdowne

[edit]

The Lansdowne complex, also known as Leverton Gardens, consists of three identical tower blocks in Highfield, a short distance to the south of Sheffield City Centre and located just off the A61 St Mary's Gate, now part of the Sheffield Inner Ring Road. Lansdowne is also located close to Hanover House. There is no nearby locale named Lansdowne, and it is not known where the name originated from. The complex is situated off Cliff Street, which connects the B6388 London Road and Cemetery Road a short distance below their junction.

Construction of the Lansdowne complex was carried out by M J Gleeson on behalf of Sheffield City Council, commencing in 1963. All three towers were completed in 1964. They are of a similar design to the towers at Callow Mount, which were also constructed by M J Gleeson. The three towers are named Gregory, Keating and Wiggen, each consisting of sixteen storeys, containing 56 two-bedroom apartments each and rising to a total height of 43 m (141 ft).[13] Fourteen of the floors are residential; both the ground floor and top floor contain communal facilities such as a laundry area. Much of the top floor was previously a communal penthouse living space with open rooftop patios, although these are now enclosed.

The addresses of the three towers are as follows:

- Gregory: 121–239 Leverton Gardens

- Keating: 1–119 Leverton Gardens

- Wiggen: 1–119 Leverton Drive

In the centre point between the bases of the three towers is a green space, also known as Leverton Gardens. All three towers were refurbished between 2007 and 2009. As part of the refurbishment project, they received their current predominantly grey exterior cladding. The Leverton Gardens green space was also refurbished, receiving new planting areas and benches.

Netherthorpe Brook Hill

[edit]

The Netherthorpe complex, also known as the Brook Hill complex, was one of two sets of tower blocks constructed as part of the Netherthorpe Redevelopment Area, the other being the Upperthorpe complex on Martin Street around 0.3 mi (0.48 km) to the north.[14] The four tower blocks at Netherthorpe are located at the head of what is now the A61 Netherthorpe Road dual carriageway, part of the Sheffield Inner Ring Road, close to the Brook Hill roundabout and the University of Sheffield.

Construction of the four tower blocks at Netherthorpe was carried out directly by Sheffield City Council municipal labour organisations, commencing in 1960 and completing in 1962. The four blocks are named Adamfield, Cornhill, Crawshaw and Robertshaw. Both Adamfield and Cornhill consist of fourteen storeys, twelve of them residential, housing 48 single-bedroom apartments and rising to 41 m (135 ft) in height. Crawshaw and Robertshaw consist of fifteen storeys, fourteen of them residential, containing 56 two-bedroom apartments and rising to 41 m (135 ft) in height.[14] All four towers contain a communal ground floor space consisting of laundry and other facilities. Due to their smaller footprint, in Adamfield and Cornhill, this space occupies the bottom two floors.

The addresses of the four towers are as follows:

- Adamfield: 1–95 Brightmore Drive

- Cornhill: 99–193 Brightmore Drive

- Crawshaw: 2–112 Mitchell Street

- Robertshaw: 2–112 Brightmore Drive

The four towers are set out in an L-shape. The two shorter towers, Adamfield and Cornhill, are located alongside each other at the top of the hill, parallel with Bolsover Street. The other two towers, Crawshaw and Robertshaw, are located one after the other leading down the hill from Adamfield, parallel with Netherthorpe Road. Robertshaw was named after Robertshaw Street, which the tower replaced; in turn, Robertshaw Street had been named after local printer and bookbinder and Justice of the Peace Jeremiah Robertshaw and his wife Sarah Robertshaw Hence Sarah Street A plaque dedicated to the Robertshaws and their contribution to industry in Sheffield can also be found at the Northern General Hospital in the north of the city.

All four towers were refurbished in 1998. As part of the refurbishment, the towers received new exterior cladding, with two similar designs used on the two sets of buildings at the complex. Adamfield and Cornhill have aqua-coloured cladding at the top and bottom fading to white in the middle, while Crawshaw and Robertshaw have lilac cladding at the top and dark blue cladding at the bottom fading to white in the middle in a similar design.

Park Hill

[edit]

Park Hill is a sprawling complex built under the streets in the sky philosophy on the hill overlooking Sheffield station to the east of Sheffield City Centre. The Park Hill site is bounded by South Street, Anson Street, Duke Street and Talbot Street; the flats replaced a large area of slums on these streets and surrounding roads such as Granville Street, which is now closed to cars and carries the course of the Sheffield Supertram tracks above Sheffield station. Park Hill was designed by Sheffield architects J. L. Womersley, Jack Lynn, I. Smith and F. Nicklin.[15] Regarded as a marvel of 1960s brutalist engineering, the Park Hill estate has been Grade II* listed since 1998; it is the largest single listed building in Europe.

Although constructed as a single expansive structure with forks and bends, Park Hill can still be subdivided into four main sections with differing numbers of floors due to the steeply sloping land it was constructed upon. The buildings facing the city centre at the northern end of the site have thirteen storeys, reducing in stages to ten, nine and finally seven storeys at the top of the hill, the southern end of the site facing Talbot Street. Despite the sloping land, Park Hill has a single flat roofline from north to south, hence the reducing number of floors.

Construction of Park Hill commenced in 1957 and was completed in 1961. When built, there were a total of 995 dwellings throughout the structure, as well as shops, pubs and other amenities.[15] The different floors of Park Hill, known as decks, were each named after roads which disappeared under the floorplan of Park Hill when the slums were cleared and the flats were constructed. Each deck is flat and wide enough to drive a milk float along in front of the individual apartment doorways. Indeed, the lower six decks can be driven onto from ground level at their southern end due to the sloping land. At the north-eastern limit of the Park Hill site is the separate boiler room, with its prominent concrete chimney still extant.

Park Hill, like the adjacent Hyde Park streets in the sky scheme and the Kelvin Flats across the city, fell into deprivation by the end of the 1980s, following the collapse of Sheffield's steel and coal industries, local economic decline and population flight away from the city. The local council were able to cut their losses by demolishing half of the Hyde Park estate and Kelvin in its entirety, although Park Hill presented a more difficult issue as it was constructed as one complete structure. After continuing to fall into disrepair, Park Hill was Grade II* listed in 1998 to protect it from demolition.

Park Hill was entirely empty by the early 2000s. Developer Urban Splash subsequently purchased the Park Hill flats from Sheffield City Council in 2006, and started an ambitious refurbishment project in 2009. Phase 1 of the project focused on the most prominent northern end of the site. The most prominent visual change was the replacement of the worn brick facade with cladding made up of multi-coloured panels, from red on the lower floors through orange to yellow on the upper floors, while retaining the listed concrete box frame. Phase 1 was completed by 2012, and upmarket private apartments were put on sale in this section of the building. Around the same time, the local council completed the development of South Street Park, a new green space located between Park Hill and the railway station.

Phase 2 of the Park Hill redevelopment commenced in 2016 and is expected to open in time for the September 2020 academic year, with the middle part of the Park Hill site refurbished into university accommodation for Sheffield Hallam University known as Béton House. Phase 3, encompassing the northern end of the site, is expected to commence following the completion of Béton House and itself be completed by the end of 2022.

Stannington Deer Park

[edit]

The Deer Park complex, also known more simply as the Stannington towers, is a set of three identical towers located on land at the southern end of the Deer Park in Stannington, an outer suburb high in the western hills of Sheffield, around 2.5 mi (4.0 km) from Sheffield City Centre. Located alongside the B6076 Stannington Road, the Deer Park complex is the westernmost set of tower blocks in Sheffield; it is considerably isolated from the Upperthorpe complex, the next nearest set of towers, more than 1.8 mi (2.9 km) away.

Construction of the three towers at Stannington commenced in 1964 and was completed in 1965. Sheffield City Council sub-contracted construction of the towers out to Wimpey Homes. The three towers are named Cliffe, Parkside and Woodland. Each tower is fifteen storeys high, with 48 single-bedroom flats in the upper fourteen floors, taking the towers to a height of 41 m (135 ft) each.[16] The ground floor of each tower is a communal lobby. Woodland is the site of the district heating system for the Stannington complex, located in a basement area below the tower, with three red metal chimneys attached to the northern face of the tower all the way to roof level.

The addresses of the three towers are as follows:

- Cliffe: 1–173 Deer Park View

- Parkside: 1–173 Deer Park Road

- Woodland: 2–174 Deer Park Close

The Deer Park towers suffered from poor construction techniques; they were one of three tower block complexes in Sheffield built by Wimpey Homes (the others being now-demolished Jordanthorpe and Pye Bank), and they suffered with draught and damp problems due to their large-scale use of Wimpey's trademark no-fines concrete, which was successful in low-rise housing but proved inappropriate for use in a high-rise tower block. The towers were in a severely dilapidated state as early as the late 1970s. Subsequently, the three towers were extensively refurbished by Sheffield City Council between 1988 and 1990, gaining their present red-brick cladding covering the previous concrete structure.[16] Due to their poor condition, Deer Park was the first tower block complex in Sheffield to undergo a significant council-funded refurbishment.

Upperthorpe

[edit]

The Upperthorpe complex, also known as the Martin Street complex, is one of two sets of tower blocks constructed as part of the Netherthorpe Redevelopment Area, the other being the Netherthorpe complex at Brook Hill around 0.3 mi (0.48 km) to the south.[17][18] Construction of the complex at Upperthorpe commenced in 1958 through building contractor Tersons Ltd., who later became part of the British Insulated Callender's Cables company, on behalf of Sheffield City Council. As a result, they are largely identical in design to the Herdings Twin Towers, which were also built by Tersons. The last blocks at Upperthorpe were completed in 1961. There are seven identical tower blocks at Upperthorpe, sited in a line on the south side of Martin Street and demarcating the northern edge of the Ponderosa park.[17][18]

The seven towers at Upperthorpe are named Adelphi, Albion, Bond, Burlington, Martin, Oxford and Wentworth.[17][18] They are each named after a former street which crossed the Upperthorpe site when it was occupied by slums, cleared to make way for the development. Each tower is identical, consisting of thirteen floors housing 48 one-bedroom apartments and rising to 38 m (125 ft) in height; the upper twelve floors are residential, with the ground floor housing communal facilities such as a laundry area.[17][18]

The addresses of the Upperthorpe towers, and their namesakes, are as follows:

- Adelphi: 97–191 Martin Street; named after Adelphi Street, the adjacent road.

- Albion: 481–575 Martin Street; named after Albion Street, the adjacent road.

- Bond: 385–479 Martin Street; named after Bond Street, which formerly crossed here but no longer exists.

- Burlington: 289–383 Martin Street; named after Burlington Street, the adjacent road.

- Martin: 193–287 Martin Street; named after Martin Street which through the development.

- Oxford: 469–563 Oxford Street; named after Oxford Street, on which it stands.

- Wentworth: 1–95 Martin Street; named after Wentworth Street, which formerly ran parallel to Martin Street but no longer exists.

All seven towers were refurbished between 1993 and 1996. As part of the refurbishment, each tower received their nearly identical white, light brown and dark brown aluminium-based cladding which they carry today, covering the original concrete structures. Martin Street was also largely pedestrianised and is no longer a single through road; areas at the base of each tower were retained for resident parking, accessed from perpendicular side streets, with the sections between towers converted into footpaths.

A fire occurred in Wentworth tower during refurbishment in 1995, which damaged several flats and portions of the cladding which was under installation at the time; there were no injuries, and the damage was repaired as part of the refurbishment programme. The cladding design here stopped the spread of the fire, in direct contrast to the later Grenfell Tower fire in London in June 2017 in which 72 people died. Following the Grenfell disaster, the cladding of all high-rises across the United Kingdom was tested to new fire safety standards. All of the Upperthorpe blocks, including Wentworth, passed inspection, although Hanover House across the city failed and had its cladding removed.

Demolished developments

[edit]Broomhall

[edit]

The Broomhall complex consisted of a sprawling network of 27 mid-rise tower blocks alongside the A61 Hanover Way, nowadays part of the Sheffield Inner Ring Road, on the edge of Sheffield City Centre in Broomhall.[19] It was located across the dual carriageway from Hanover House. In terms of design, the development at Broomhall can be thought of as a condensed version of the Park Hill estate, as they were both built to the same streets in the sky philosophy with deck access to properties. The Broomhall complex was constructed in 1967 by a consortium headed by the Shepherd Building Group and the Yorkshire Development Group.[19] There were a total of 619 dwellings at the Broomhall complex, with twenty 7-storey blocks of flats containing 23 dwellings each and seven 6-storey blocks containing 21 dwellings each.[19]

The Broomhall complex fell into social decline into the 1980s, disadvantaged by its location sprawling across a very large site in the heart of the inner city. One of the many issues at the complex was the emergence of a red-light district. The Broomhall complex was vacated in the mid-1980s and demolished in 1987.[19] The site is now occupied by a mixture of low-rise student accommodation buildings on the side closest to the University of Sheffield and low-rise general apartments, now housing a large Somali community, on the side closest to the city centre.

The only remaining structure from the Broomhall estate is a former pub, known as The Domino, built to a hexagonal plan. It has now been converted into student accommodation, integrated with surrounding new-builds.

Chapeltown Bath House

[edit]

The Chapeltown complex, also known as the Bath House site due to their proximity to the Chapeltown swimming baths, consisted of three 12-storey tower blocks along the B6546 Burncross Road in Chapeltown.[20] The three towers at Chapeltown were named Britannia Court, Habershon Court and Hallamshire Court. Each tower was identical, containing 66 dwellings, and all three were constructed in 1964 by contractors Reed & Mallik on behalf of Wortley Rural District Council.[20] Chapeltown and The Fosters were the only high-rises within the modern day boundaries of Sheffield that were not built for Sheffield City Council or its predecessors, although both did come under the control of the city council towards the ends of their lives as the city limits were extended.

During construction of the complex, one of the tower cranes on site collapsed, destroying three low-rise housing blocks which were also under construction at the time; there were no reported injuries. The towers of the Chapeltown complex were built to a similar design as the Ronan Point tower in London, including featuring a very similar gas heating system. Following the gas explosion at Ronan Point and its partial collapse in 1968, the gas heating system at Chapeltown was abandoned in favour of electric heaters in each dwelling; however, concerns over the safety of the complex persisted due to their use of Reema construction techniques, which has caused considerable problems in other high-rises across the country.

A severe fire broke out on the fourth floor of Habershon Court in 1986; although nobody was injured, the damage from the fire was severe and was never repaired, and the decision was taken to vacate and demolish the Chapeltown complex two years later. All three blocks were manually demolished in 1990,[20] only 26 years after their construction, and the site now consists of low-rise detached housing on a new cul-de-sac named Burncross Drive.

Claywood

[edit]

The Claywood complex was a set of three tall tower blocks located on the hillside rising to the immediate east of Sheffield City Centre, at the northern edge of the Park Grange suburb. Claywood was located immediately south of Park Hill over the opposite side of Talbot Street, with access to the towers provided from Claywood Drive, a cul-de-sac from Norfolk Road. Their height and hillside location meant the Claywood flats were very prominent when viewed from across the city centre, particularly looking up from Sheffield station. In terms of design, the Claywood towers were similar to those nearby at Norfolk Park, which have also been demolished, although they contained similar yellow panel detailing to pre-refurbishment Hanover House.

The three Claywood towers were named Claywood, Fitzwalter and Norfolk. They were built by M J Gleeson, and construction took place in 1967. Each of the three towers were largely identical, consisting of 17 floors containing 127 apartments each and rising to heights of 46 m (151 ft).[21]

The Claywood tower blocks were deconstructed with specialist machinery (rather than by controlled explosion) in early 2005, as part of the wider Norfolk Park regeneration. As of June 2020, the Claywood site remains empty. Claywood Drive still exists, although it is now merely a footpath which provides access to the Cholera Monument Grounds and Clay Wood city park.

Jordanthorpe

[edit]

The Jordanthorpe complex was a set of three identical tower blocks located in the centre of the Jordanthorpe housing estate in south-central Sheffield. The Jordanthorpe estate, including surrounding low-rise housing and maisonette blocks, was constructed in the 1950s and 1960s on land acquired by Sheffield City Council by compulsory purchase from neighbouring Derbyshire, and subsequently annexed into the territory of the West Riding of Yorkshire. They were the southernmost tower blocks in Sheffield.

The three towers at Jordanthorpe were built by Wimpey Homes of an identical design to those at Pye Bank, now also demolished, and Stannington, which still exist albeit now in a heavily refurbished state.[22] Construction began at Jordanthorpe in 1966, and the three towers were completed in 1967. The three towers were identical in design, consisting of fifteen storeys containing 87 single-bedroom apartments each and rising to heights of 41 m (135 ft).[22] The upper fourteen storeys were residential, with the ground floor dedicated as communal space.

The towers were named Chantrey, Ramsey and Rhodes. Although directly adjacent to each other, they were all accessed via individual cul-de-sacs branching from the main ring road, Dyche Road, in the centre of the estate; Chantrey was located on Dyche Drive, Ramsey on Dyche Place, and Rhodes on Dyche Close.

Very soon after completion, as with the Wimpey-built towers at Pye Bank and Stannington, problems with heating, draughts and damp became evident due to the wide-scale use of Wimpey no-fines concrete in their construction. Unlike the Stannington complex, however, the Jordanthorpe complex was not refurbished to address these issues at the end of the 1980s, due to funding constraints at Sheffield City Council. The condition of the towers eventually deteriorated until Ramsey and Rhodes were condemned at the turn of the 21st century, before being demolished in October 2001 by controlled explosion as part of the council's stock reduction plan.

Chantrey was in slightly better condition, and after minor remedial work, remained in use as residencies reserved for people over State Pension age. This did not last long however, as it too was condemned a decade later. Chantrey was subsequently demolished on 29 April 2012 using controlled explosives, with demolition being carried out by Demex Ltd., a local contractor.[23]

The site of the Jordanthorpe tower blocks remains the centre of the wider Jordanthorpe housing estate, and the footprints of all three towers have since been redeveloped into a medical centre, a nursing home, and semi-detached low-rise housing on Dyche Drive.

Kelvin Flats

[edit]

The Kelvin Flats were an expansive deck access, streets in the sky high-rise complex constructed in a similar style to Hyde Park and Park Hill across the city. Kelvin was designed by J. L. Womersley, who also designed Hyde Park and Park Hill, and W. L. Clunie, who was involved in the development of the former.[24] Construction of the two thirteen-storey blocks at Kelvin, containing a total of 948 dwellings, was carried out by the direct municipal labour groups of Sheffield City Council and was completed in 1967.[24]

Kelvin consisted of two separate blocks of deck access flats alongside Infirmary Road in the Neepsend area of the city, between Upperthorpe and Walkley to the north of Sheffield City Centre. The larger of the three blocks was split into three sections named Edith Walk, Portland Walk and Woollen Walk, while the smaller block was named Kelvin Walk in its entirety.[24] The Kelvin complex became one of the most deprived areas of the city by the mid-1980s, following the decline of the local steel and coal industries, economic collapse and subsequent population flight away from Sheffield. For security reasons around this time, the doors to each flat were replaced with high-security doors at a cost of £1,000 per flat, or nearly £1 million across the whole complex.

Security improvements at Kelvin were not enough to save the complex, which had also began to fall into severe structural disrepair. Sheffield City Council decided to demolish the now largely abandoned Kelvin complex in its entirety in 1995. The basketball courts and other leisure facilities that were formerly in the centre of the estate were retained, were subsequently refurbished, and now constitute a standalone green space. The area where the high-rises once stood is now occupied by Philadelphia Gardens, a late 1990s low-rise detached housing estate; one of the new streets is named Portland Court, after one of the former walks at Kelvin.

Lowedges

[edit]

The Lowedges complex, also known during development as the Greenhill–Bradway redevelopment after the two suburbs it lies between,[25] was a set of three identical tower blocks and surrounding low-rise suburban and maisonette housing constructed as part of the Lowedges estate in the 1950s, similarly to the later Jordanthorpe estate adjacent. Unlike most complexes, the three towers at Lowedges were not directly adjacent to each other, instead being spread across the east–west axis of the Lowedges estate. The three towers each consisted of thirteen storeys, containing 48 single-bedroom apartments and rising to heights of 38 m (125 ft).[25]

The three towers at Lowedges were constructed between 1958 and 1959 on behalf of Sheffield City Council by Tersons Ltd., who later became part of the British Insulated Callender's Cables company.[25] As such, they were mostly identical to the tower blocks at Upperthorpe and the Herdings Twin Towers, which still exist, albeit now in a heavily refurbished state. Two of the towers, named Atlantic 1 and Atlantic 2, were situated on Atlantic Road; Atlantic 1 was located at the junction of Atlantic Road and Becket Road, while Atlantic 2 was located at the corner of Atlantic Road and Gervase Road. The third tower, named Gervase, was located on Gervase Avenue opposite the junction with Gervase Place.

The Lowedges complex was demolished in stages between 2001 and 2002, starting with Atlantic 1 and ending with Gervase, as part of Sheffield City Council's stock reduction plan to cut the council housing budget. The footprints of all three buildings remain unoccupied as of June 2020, and are visible as green spaces amongst the surrounding low-rise housing. The standalone garages next to Atlantic 1 and Atlantic 2 were not demolished and are still in use, now belonging to the adjacent maisonettes.

Norfolk Park

[edit]

The Norfolk Park complex was one of the largest residential high-rise complexes ever constructed in the United Kingdom, consisting of fifteen blocks of seventeen-storey flats containing a total of 1,887 individual apartments located next to Norfolk Heritage Park.[26][27][28][29] Constructed in four distinct phases between 1963 and 1967, the 46 m (151 ft) tall tower blocks at Norfolk Park were all constructed to a largely identical design by M J Gleeson and Sheffield City Council municipal labour groups. The Norfolk Park towers were situated for the most part lining either side of Park Grange Road, rising from the bottom of the hill close to Sheffield City Centre at the northern end to the top of the hill next to the Manor estate at the southern end.[26][27][28][29]

Sheffield was in desperate need of replacement housing stock by the early 1960s, following widespread slum clearances. The situation was compounded by The Sheffield Gale of 16 February 1962, which killed three people in the city and damaged more than 175,000 houses across Sheffield, many beyond repair.[30] Construction of the expansive Norfolk Park scheme commenced in earnest the following year. The towers were similar in design to the nearby Claywood blocks, which have also been demolished; their closest existing equivalent is Hanover House, which is effectively a shorter version of the design used at Norfolk Park.

The towers were generally located in clusters of two or three at a time, placed sporadically on the hillside rising southeast from the city centre and surrounded by contemporary low-rise housing; many of them were served by their own cul-de-sacs branching short distances away from Park Grange Road, the main thoroughfare. Each tower was named. Bankside was located on Guildford Close; Beechview on Guildford Drive; East Bank and Spring on Park Grange Mount; Fitzalan on St. Aidan's Close; Grange on Tower Drive; Granville on St. Aidan's Mount; Guildford and Shrewsbury on Guildford View; Howard on St. Aidan's Drive; Jervis on Beeches Drive; Mandrake on Park Grange View; Mickley on Beldon Close; and Talbot on Kenninghall Mount.

Many of the blocks fell into disrepair and social decline during their final years. All fifteen towers were demolished via controlled explosion between 1997 and 2005 as part of Sheffield City Council's stock reduction plan in order to cut the council housing budget. Mandrake was the first tower to be demolished, by mechanical means in early 1997, followed by East Bank and Jervis by controlled explosion, on 8 June 1997. Fitzalan, Granville, Guildford, Howard and Shrewsbury were demolished in 1999. Bankside, Beechview, Spring and Talbot were demolished in 2001 and 2002. Mickley was the penultimate block to be demolished, on 11 January 2004, followed finally by Grange, on 24 April 2005.

The Norfolk Park area underwent a significant redevelopment throughout the 2000s and 2010s. As well as the tower blocks, much of the surrounding low-rise housing was either demolished or refurbished. In their place, and in place of most of the towers, new low-rise detached and semi-detached housing and mid-rise apartment blocks were constructed, with some development at the western end of Norfolk Park adjoining East Bank Road still under construction as of June 2020. Norfolk Park Medical Centre was constructed on the site of Mickley tower between 2010 and 2011, and the footprints of some towers remain empty pending redevelopment.

Middlewood Winn Gardens

[edit]

The Middlewood tower block was constructed as the centrepiece of the Winn Gardens housing estate. The Winn Gardens estate is located just off the A6102 Middlewood Road in Middlewood, near Hillsborough in the north of the city. Constructed at the same time as the tower surrounding its base were six blocks of mid-rise maisonettes, with further low-rise terraced housing constructed in a loose grid plan around the edges of the estate.

The tower block at Middlewood, located on Winn Grove next to the Winn Gardens shopping parade, was constructed in 1962 by municipal labour groups of the Sheffield City Council. It consisted of thirteen storeys, containing 48 apartments and rising to 40 m (130 ft) in height.[31] As they were all constructed directly by the council, the single Middlewood tower was most similar in basic layout and design to those at Netherthorpe, which still exist, albeit now in a heavily refurbished state. However, the Middlewood tower was slightly shorter than those at Netherthorpe.

The single Middlewood tower block was demolished manually in 2004. The maisonettes, low-rise housing and other structures which make up the Winn Gardens estate still exist. As of June 2020, the former footprint of the tower block remains undeveloped, visible as a small area of green space amongst the maisonettes. The standalone garages which once belonged to the tower were not demolished and nowadays remain in use as car parking for the maisonettes.

Pye Bank

[edit]

The Pye Bank complex was constructed as part of the wider Woodside Lane Redevelopment Area, covering much of the Burngreave area just north of Sheffield City Centre. The Pye Bank estate was designed by city architect J. L. Womersley and constructed by Wimpey Homes in the late 1950s and early 1960s, consisting of a mixture of low, mid and high-rise housing.[32] The four tower blocks were located on the western side of Pitsmoor Road, with a line of nine six-storey maisonette blocks between Pitsmoor Road and Pye Bank Road containing a total of 156 apartments.[32] The low-rise houses were mostly terraced in style and built with unusual multiple-domed roofs, infilling much of the remaining space in between Victorian terraces between Pye Bank Road and Fox Street.

All four tower blocks were constructed in 1960. Two of the towers consisted of thirteen floors containing 48 apartments each and were similar in design to those later built by Wimpey Homes across the city at Jordanthorpe and Stannington. The other two towers were of a slightly taller version, rising to fifteen storeys in height and containing 56 apartments each.[32]

The widespread use of Wimpey's trademark no-fines concrete in the construction of the maisonettes and tower blocks meant they suffered from severe draught and damp issues from not long after construction, and rapidly fell into structural decline. Issues with the Pye Bank estate were compounded by social decline in the mid-1980s following the collapse of the local steel and coal industries, decimation of the local economy and population flight away from Sheffield. The Wimpey towers at Stannington were refurbished in the late 1980s to rectify their issues, however those at Jordanthorpe and Pye Bank were not and were all subsequently condemned and demolished in the 1990s and 2000s.

Not much today remains of the Pye Bank estate. All four tower blocks were demolished in 1995. All of the maisonettes and most of the low-rise housing followed, undergoing demolition between 2002 and 2005. Just thirteen residences of the unique low-rise multi-dome terrace design remain standing as of June 2020: seven on Fox Street (in two blocks of four and three) and six in a single row on Pye Bank Road. The site of the tower blocks and maisonettes remains as undeveloped grassland. Opened in September 2019, the Astrea Academy Sheffield secondary school now occupies the site of most of the demolished low-rise terraces.

The Fosters

[edit]

The Fosters, originally known as Angram Bank, was a single tower block located on Foster Way in High Green in the far north of Sheffield. It was the northernmost tower block in the city. It consisted of ten storeys containing 34 apartments and rising to a height of 38 m (125 ft).[33] The upper nine floors were residential, with the ground floor set aside for communal facilities.

The Fosters was constructed between 1966 and 1967 by JF Finnegan Ltd. on behalf of Wortley Rural District Council.[33] The Fosters and the Chapeltown complex were the only high-rises within the modern-day boundaries of Sheffield that were not built for Sheffield City Council or its predecessors, although both did come under the control of the city council towards the ends of their lives as the city limits were extended.

The tower fell into disrepair during the 1990s, and had been cleared of all residents and abandoned entirely by the start of the 2000s due to structural concerns. After lying empty for a number of years, Sheffield City Council granted permission for The Fosters to be demolished in 2011. Demolition via manual methods commenced in September 2011 and was completed by the end of the year. A small low-rise residential estate, also named The Fosters, was completed on the site of the tower in 2015; it consists of two blocks of modern terraced housing.

See also

[edit]- Glasgow tower blocks

- List of council high-rise apartment buildings in the City of Leeds

- List of tallest buildings and structures in Sheffield

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Bennett, Larry (1997). Neighborhood politics: Chicago and Sheffield. Taylor & Francis. pp. 97–100. ISBN 0-8153-2113-9.

- ^ Harman, R.; Minnis, J. (2004). Pevsner City Guides: Sheffield. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 209. ISBN 0-300-10585-1.

- ^ a b "Gleadless Valley (Rollestone)". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Newsroom, The (19 April 2016). "RETRO: The birth of Gleadless Valley, the 'jewel in Sheffield's crown'". The Sheffield Star. JPIMedia Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ a b "Gleadless Valley". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Gleadless Valley master plan". Sheffield City Council. GOV.UK. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "Hanover". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "Cladding to be removed from Sheffield tower block". BBC News. 26 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Gleadless Valley (Herdings)". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "Demolition of the 13 Storey Tower Block at Herdings, Sheffield". YouTube. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Park Hill, Part Two". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Sheffield Flats, Park Hill and Hyde Park, Peter Tuffrey, Fonthill Media Ltd, 2013, ISBN 978 1 78155 054 0, Details of re-development.

- ^ "Lansdowne". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Netherthorpe Redevelopment Area (Brook Hill)". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Park Hill, Part One". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Stannington". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Netherthorpe Redevelopment Area (Martin Street)". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Netherthorpe Redevelopment Area (Martin Street)". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Broomhall". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Bath House Site, Burncross Road, Chapeltown". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "Claywood". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Jordanthorpe". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "The Chantry Tower Block Demolition, Jordanthorpe, Sheffield". YouTube. rocketandspade. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Kelvin". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Greenhill-Bradway". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Norfolk Park". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Norfolk Park". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Norfolk Park". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Norfolk Park". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Philip Eden (1 January 2012). "Newsletter 1, 2012" (PDF). Royal Meteorological Society. p. 8. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "Middlewood". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Woodside Lane Redevelopment Area". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Angram Bank, High Green: Central Development". Tower Block UK. The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 June 2020.