Liverpool and Manchester Railway

A lithograph of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway crossing the Bridgewater Canal at Patricroft, by A. B. Clayton. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Liverpool |

| Locale | Lancashire |

| Dates of operation | 1830–1845 |

| Successor | Grand Junction Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 31 miles (50 km) |

Liverpool and Manchester Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1830–1845 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

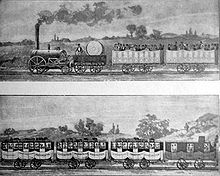

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway[1][2][3] (L&MR) was the first inter-city railway in the world.[4][i] It opened on 15 September 1830 between the Lancashire towns of Liverpool and Manchester in England.[4] It was also the first railway to rely exclusively on locomotives driven by steam power, with no horse-drawn traffic permitted at any time; the first to be entirely double track throughout its length; the first to have a true signalling system; the first to be fully timetabled; and the first to carry mail.[5]

Trains were hauled by company steam locomotives between the two towns, though private wagons and carriages were allowed. Cable haulage of freight trains was down the steeply-graded 1.26-mile (2.03 km) Wapping Tunnel to Liverpool Docks from Edge Hill junction. The railway was primarily built to provide faster transport of raw materials, finished goods, and passengers between the Port of Liverpool and the cotton mills and factories of Manchester and surrounding towns.

Designed and built by George Stephenson, the line was financially successful, and influenced the development of railways across Britain in the 1830s. In 1845 the railway was absorbed by its principal business partner, the Grand Junction Railway (GJR), which in turn amalgamated the following year with the London and Birmingham Railway and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway to form the London and North Western Railway.[6]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]

During the Industrial Revolution, huge tonnages of raw material were imported through Liverpool and carried to the textile mills near the Pennines where water, and later steam power, enabled the production of the finished cloth, much of which was then transported back to Liverpool for export.[7][8] The existing means of water transport, the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, the Bridgewater Canal and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, dated from the 18th century, and were felt to be making excessive profits from the cotton trade and throttling the growth of Manchester and other towns.[9][10] Goods were transported between Liverpool and the factories around Manchester either by the canals or by poor-quality roads; the turnpike between Liverpool and Manchester was described as "crooked and rough" with an "infamous" surface.[10] Road accidents were frequent, including waggons and coaches overturning, which made goods traffic problematic.[11]

The proposed railway was intended to achieve cheap transport of raw materials, finished goods and passengers between the Port of Liverpool and east Lancashire, in the port's hinterland. There was support for the railway from both Liverpool and London but Manchester was largely indifferent and opposition came from the canal operators and the two local landowners, the Earl of Derby and the Earl of Sefton, over whose land the railway would cross.[9][12]

The proposed Liverpool and Manchester Railway was to be one of the earliest land-based public transport systems not using animal traction power. Before then, public railways had been horse-drawn, including the Lake Lock Rail Road (1796),[13] Surrey Iron Railway (1801) and the Oystermouth Railway near Swansea (1807).[14]

Formation

[edit]

The original promoters are usually acknowledged to be Joseph Sandars, a rich Liverpool corn merchant, and John Kennedy, owner of the largest spinning mill in Manchester. They were influenced by William James.[15][16][17] James was a land surveyor who had made a fortune in property speculation. He advocated a national network of railways, based on what he had seen of the development of colliery lines and locomotive technology in the north of England.[18]

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company was founded on 20 May 1824.[19] It was established by Henry Booth, who became its secretary and treasurer, along with merchants from Liverpool and Manchester. Charles Lawrence was the Chairman, Lister Ellis, Robert Gladstone, John Moss and Joseph Sandars were the Deputy Chairmen.[20]

| Liverpool and Manchester Railway Act 1826 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Citation | 7 Geo. 4. c. xlix |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 5 May 1826 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Grand Junction Railway Act 1845 |

Status: Repealed | |

A bill was drafted in 1825 to Parliament, which included a 1-inch to the mile map of the railway's route.[21] The first bill was rejected but the second passed as the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Act 1826 (7 Geo. 4. c. xlix) in May the following year.[22] In Liverpool 172 people bought 1,979 shares, in London 96 took 844, Manchester 15 with 124, 24 others with 286. The Marquess of Stafford held 1,000, making 308 shareholders with 4,233 shares.

Survey and authorisation

[edit]

The first survey for the line was carried out by James in 1822. The route was roughly the same as what was built, but the committee were unaware of exactly what land had been surveyed. James subsequently declared bankruptcy and was imprisoned that November. The committee lost confidence in his ability to plan and build the line[23] and, in June 1824, George Stephenson was appointed principal engineer.[24] As well as objections to the proposed route by Lords Sefton and Derby, Robert Haldane Bradshaw, a trustee of the Duke of Bridgewater's estate at Worsley, refused any access to land owned by the Bridgewater Trustees and Stephenson had difficulty producing a satisfactory survey of the proposed route and accepted James' original plans with spot checks.[25][24]

The survey was presented to Parliament on 8 February 1825,[26] but was shown to be inaccurate. Francis Giles suggested that putting the railway through Chat Moss was a serious error and the total cost of the line would be around £200,000 instead of the £40,000 quoted by Stephenson.[27] Stephenson was cross examined by the opposing counsel led by Edward Hall Alderson and his lack of suitable figures and understanding of the work came to light. When asked, he was unable to specify the levels of the track and how he calculated the cost of major structures such as the Irwell Viaduct. The bill was thrown out on 31 May.[28][29]

In place of George Stephenson, the railway promoters appointed George and John Rennie as engineers, who chose Charles Blacker Vignoles as their surveyor.[30] They set out to placate the canal interests and had the good fortune to approach the marquess[clarification needed] directly through their counsel, W. G. Adam, who was a relative of one of the trustees, and the support of William Huskisson who knew the marquess personally.[31] Implacable opposition to the line changed to financial support.[32]

The second bill received royal assent as the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Act 1826 (7 Geo. 4. c. xlix) on 5 May 1826.[33] The railway route ran on a significantly different alignment, south of Stephenson's, avoiding properties owned by opponents of the previous bill. From Huyton the route ran directly east through Parr Moss, Newton, Chat Moss and Eccles. In Liverpool, the route included a 1.25-mile (2.01 km) tunnel from Edge Hill to the docks, avoiding crossing any streets at ground level.[32] It was intended to place the Manchester terminus on the Salford side of the River Irwell, but the Mersey and Irwell Navigation withdrew their opposition to a crossing of the river at the last moment in return for access for their carts over the intended railway bridge. The Manchester station was therefore fixed at Liverpool Road in Castlefield.[34]

Construction

[edit]

The first contracts for draining Chat Moss were let in June 1826. The Rennies insisted that the company should appoint a resident engineer, recommending either Josias Jessop or Thomas Telford, but would not consider George Stephenson except in an advisory capacity for locomotive design.[35] The board rejected their terms and re-appointed Stephenson as engineer with his assistant Joseph Locke.[36] Stephenson clashed with Vignoles, leading to the latter resigning as resident Surveyor.[37]

The line was 31-mile (50 km) long.[38] Management was split into three sections. The western end was run by Locke, the middle section by William Allcard and the eastern section including Chat Moss, by John Dixon.[39] The track began at the 2,250-yard (2.06 km) Wapping Tunnel beneath Liverpool from the south end of Liverpool Docks to Edge Hill.[40] It was the world's first tunnel to be bored under a metropolis.[41] Following this was a 2-mile (3 km) long cutting up to 70 feet (21 m) deep through rock at Olive Mount,[42] and a 712-foot (217 m) nine-arch viaduct, each arch of 50 feet (15 m) span and around 60 feet (18 m) high) over the Sankey Brook valley.[43]

The railway included the 4+3⁄4-mile (7.6 km) crossing of Chat Moss. It was found impossible to drain the bog and so the engineers used a design from Robert Stannard, steward for William Roscoe, that used wrought iron rails supported by timber in a herring bone layout.[44] About 70,000 cubic feet (2,000 m3) of spoil was dropped into the bog; at Blackpool Hole, a contractor tipped soil into the bog for three months without finding the bottom.[45] The line was supported by empty tar barrels sealed with clay and laid end to end across the drainage ditches either side of the railway.[46] The railway over Chat Moss was completed by the end of 1829. On 28 December, the Rocket travelled over the line carrying 40 passengers and crossed the Moss in 17 minutes, averaging 17 miles per hour (27 km/h).[47] In April the following year, a test train carrying a 45-ton load crossed the moss at 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) without incident.[48] The line now supports locomotives 25 times the weight of the Rocket.[citation needed]

The railway needed 64 bridges and viaducts,[4] all built of brick or masonry, with one exception: the Water Street bridge at the Manchester terminus. A cast iron beam girder bridge was built to save headway in the street below. It was designed by William Fairbairn and Eaton Hodgkinson, and cast locally at their factory in Ancoats. It is important because cast iron girders became an important structural material for the growing rail network.[49] Although Fairbairn tested the girders before installation, not all were so well designed, and there were many examples of catastrophic failure in the years to come, resulting in the Dee bridge disaster of 1847 and culminating in the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879.

The line was laid using 15-foot (4.6 m) fish-belly rails at 35 lb/yd (17 kg/m), laid either on stone blocks or, at Chat Moss, wooden sleepers.[50][51]

The physical work was carried out by a large team of men, known as "navvies", using hand tools. The most productive teams could move up to 20,000 tonnes of earth in a day and were well paid.[52] Nevertheless, the work was dangerous and several deaths were recorded.[53]

Cable or locomotive haulage

[edit]

In 1829 adhesion-worked locomotives were not reliable. The experience on the Stockton and Darlington Railway was well-publicised, and a section of the Hetton colliery railway had been converted to cable haulage. The success of the cable haulage was indisputable but the steam locomotive was still untried. The L&MR had sought to de-emphasise the use of steam locomotives during the passage of the bill, the public were alarmed at the idea of monstrous machines which, if they did not explode, would fill the countryside with noxious fumes.

Attention was turning towards steam road carriages, such as those of Goldsworthy Gurney's and there was a division in the L&MR board between those who supported Stephenson's "loco-motive" and those who favoured cable haulage, the latter supported by the opinion of the engineer, John Rastrick. Stephenson was not averse to cable haulage—he continued to build such lines where he felt it appropriate—but knew its main disadvantage, that any breakdown anywhere would paralyse the whole line.

The line's gradient was designed to concentrate the steep grades in three places, at either side of Rainhill at 1 in 96 and down to the docks at Liverpool at 1 in 50[citation needed]) and make the rest of the line very gently graded, no further than 1 in 880.[50] When the line opened, the passenger section from Edge Hill to Crown Street railway station was cable hauled, as was the section through the Wapping Tunnel, as the act of Parliament[which?] forbade the use of locomotives on this part of the line.[54]

To determine whether and which locomotives would be suitable, in October 1829 the directors organised a public competition, known as the Rainhill trials, which involved a run along a 1 mile (1.6 km) stretch of track.[55] Ten locomotives were entered for the trials, but on the day of the competition only five were available to compete:[56] Rocket, designed by George Stephenson and his son, Robert, was the only one to successfully complete the journey and, consequently, Robert Stephenson and Company were awarded the locomotive contract.[57]

Double track

[edit]The line was built to 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) (standard gauge) and double track.[39] A decision had to be made about how far apart the two tracks should be. It was decided to make the space between the separate tracks the same as the track gauge itself, so that it would be possible to operate trains with unusually wide loads up the middle during quiet times. Stephenson was criticised for this decision;[39] it was later decided that the tracks were too close together, restricting the width of the trains, so the gap between tracks (track centres) was widened. The narrowness of the gap contributed to the first fatality, that of William Huskisson, and also made it dangerous to perform maintenance on one track while trains were operating on the other.[citation needed] Even in the 21st century, adjacent tracks on British railways tend to be laid closer together than elsewhere.[58]

Opening

[edit]

The line opened on 15 September 1830 with termini at Manchester, Liverpool Road (now part of the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester) and Liverpool Crown Street. The festivities of the opening day were marred when William Huskisson, the Member of Parliament for Liverpool, was killed.[17] The southern line was reserved for the special opening train, drawn by the locomotive Northumbrian conveying the Duke of Wellington, the Prime Minister, in an ornamental carriage, together with distinguished guests in other carriages.[59] When the train stopped for water at Parkside, near Newton-le-Willows, it was intended that the other trains should pass in review on the northern line.[60][61] It was easy for passengers to get down and stretch their legs, despite being instructed not to, particularly as there was an interval between the delayed passing trains. Huskisson decided to alight and stroll alongside the train, and on spotting the Duke decided to start a conversation. The Rocket was spotted heading in the opposite direction as people shouted at Huskisson to get back on the train.[62][63]

The Austrian ambassador was pulled back into the carriage, but Huskisson panicked.[64] He tried to climb into the carriage, but grabbed the open door, which swung back, causing him to lose his grip. He fell between the tracks and the Rocket ran over his leg, shattering it. He is reported to have said, "I have met my death—God forgive me!"[63]

The Northumbrian was detached from the Duke's train and rushed him to Eccles, where he died in the vicarage.[65] Thus he became the world's first widely reported railway passenger fatality. The somewhat subdued party proceeded to Manchester, where, the Duke being deeply unpopular with the weavers and mill workers, they were given a lively reception, and returned to Liverpool without alighting.[66] A grand reception and banquet had been prepared for their arrival.

Operation

[edit]

The L&MR was successful and popular, and reduced journey times between Liverpool and Manchester to two hours.[67] Most stage coach companies operating between the two towns closed shortly after the railway opened as it was impossible to compete.[68] Within a few weeks of the line opening, it ran its first excursion trains and carried the world's first railway mail carriages;[69] by the summer of 1831, it was carrying special trains to the races.[70] The railway was a financial success, paying investors an average annual dividend of 9.5% over the 15 years of its independent existence: a level of profitability that would never again be attained by a British railway company.[71]

The railway was purposefully designed for the benefit of the public, carrying passengers as well as freight. Shares in the company were limited to ten per person and profits from these were limited.[72] Although the intention had been to carry goods, the canal companies reduced their prices, leading to a price war between them and the railway.[73] The line did not start carrying goods until December, when the first of some more powerful engines, Planet, was delivered.

The line's success in carrying passengers was universally acclaimed.[72] The experience at Rainhill had shown that unprecedented speed could be achieved and travelling by rail was cheaper and more comfortable than travel by road. The company concentrated on passenger travel, a decision that had repercussions across the country and triggered the "railway mania of the 1840s".[74] John B. Jervis of the Delaware and Hudson Railway some years later wrote: "It must be regarded ... as opening the epoch of railways which has revolutionised the social and commercial intercourse of the civilized world".[75]

At first trains travelled at 16 miles per hour (26 km/h) carrying passengers and 8 miles per hour (13 km/h) carrying goods because of the limitations of the track.[76] Drivers could, and did, travel more quickly, but were reprimanded: it was found that excessive speeds forced apart the light rails, which were set onto individual stone blocks without cross-ties.[citation needed] In 1837 the original fish-belly parallel rail of 50 pounds per yard (24.8 kg/m), on sleepers started to be replaced.[77]

The railway directors realised that Crown Street was too far away from the centre of Liverpool to be practical, and decided in 1831 to construct a new terminus at Lime Street.[78] The tunnel from Edge Hill to Lime Street was completed in January 1835 and opened the following year. The station opened on 15 August 1836 before it had been completed.[79]

On 30 July 1842, work started to extend the line from Ordsall Lane to a new station at Hunts Bank in Manchester that also served the Manchester and Leeds Railway. The line opened on 4 May 1844 and Liverpool Road station was then used for goods traffic.[80]

On 8 August 1845, the L&MR was absorbed by its principal business partner, the Grand Junction Railway (GJR), which had opened the first trunk railway from Birmingham to Warrington in 1837.[81] The following year the GJR formed part of the London and North Western Railway.[82]

Signalling

[edit]

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the first railway to have a system of signalling.[5] This was undertaken by policemen, who were stationed along the line at distances of a mile or less.[83] Initially these policemen signalled that the line was clear by standing straight with their arms outstretched. If the policeman was not present, or was standing at ease, this indicated that there was an obstruction on the line ahead.[83] Gradually a system of hand-held flags was developed, with a red flag being used to stop a train, green indicating that a train should proceed at caution, blue indicating to drivers of baggage trains that there were new wagons for them to take on and a black flag being used by platelayers to indicate works on the track.[83] Any flag waved violently, or at night a lamp waved up and down, indicated that a train should stop.[84] Until 1844 handbells were used as emergency signals in foggy weather, though in that year small explosive boxes placed on the line began to be used instead.[85]

Trains were controlled on a time interval basis: policemen signalled for a train to stop if less than ten minutes had elapsed since a previous train had passed; the signal to proceed at caution was given if more than ten minutes but less than seventeen minutes had passed; otherwise the all clear signal was given.[86] If a train broke down on the line, the policeman had to run a mile down the track to stop oncoming traffic.[87]

After the opening of the Warrington and Newton Railway four policemen were placed constantly on duty at Newton Junction, at the potentially dangerous points where the two lines met.[84] Initially a gilt arrow was used to point towards Warrington to indicate that the points were set in that direction, with a green lamp visible from the L&MR line being used to indicate this at night.[84] Later a fixed signal was used, with red and white chequered boards on 12-foot high posts being turned to face trains from one direction if another train was ahead.[84]

In 1837 the London and Birmingham Railway conducted trials using a Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph to direct signalling[85] and in 1841 held a conference to propose a uniform national system of coloured signals to control trains,[88] but despite these advances elsewhere the Liverpool and Manchester Railway continued to be controlled by policemen and flags until its merger with the Grand Junction Railway in 1845.[89]

Significance

[edit]

On opening the L&MR represented a significant advance in railway operation, introducing regular commercial passenger and freight services by steam locomotives with significant speed and reliability improvements from their predecessors and horse carriages.[90] The L&MR operation was studied by other upcoming railway companies as a model to aspire to.[90] More recently some have claimed the operation was the first Inter-city railway,[4] though that branding was not introduced until many years later and neither Manchester or Liverpool achieved city status until 1853 and 1880 respectively, nor would the distance between them qualify as long-haul.

The subsequently widely adopted gauge of 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) was derived from a George Stephenson recommendation that was accepted at an L&MR board meeting in July 1826: "Resolved that the width of the Wagon Way between the rails to be the same as the Darlington Road, namely 4 feet 8 inches clear, inside the rails".[39][ii] This enabled the Stephensons to test their locomotives on the lines around Newcastle on Tyne[iii] before shipment to Lancashire.[91]

The L&MR used left hand running on double track, following practice on British roads. The form of couplings using buffers, hooks and chains, and their dimensions, set the pattern for European practice and practice in many other places.

Even before the L&MR opened, connecting and other lines were planned, authorised or under construction, such as the Bolton and Leigh Railway.

Incidents

[edit]The best-known accident associated with the L&MR was the death of William Huskisson, hit by the locomotive Rocket on the opening day.[63] Thereafter the pioneering and evolving nature of the early days of the L&MR meant accidents were not uncommon. All were investigated by the L&MR board or Management Committee. Fatal accidents to travelling passengers were rare, the first two years seeing one for over a million passengers carried, though injuries were more commonplace. These were often caused by passengers failing to heed company regulations and advice. Staff accidents were more commonplace, with some staff preparing to take what later would be considered to be inadvisable risks and disregarding regulations. Locomotives, wagons and infrastructure were involved in a variety of collisions and derailments. [92]

On 23 December 1832, a passenger train ran into the rear of another passenger train at Rainhill. A passenger was killed and several were injured.[93] On 17 April 1836, a passenger train was derailed whilst travelling at 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) when an axle of a carriage broke. There were no fatalities.[94]

Modern line

[edit]The original Liverpool and Manchester line still operates as a secondary line between the two cities—the southern route, the former Cheshire Lines Committee route via Warrington Central is for the moment the busier route. This however has already started to change (from the May 2014 timetable) with new First TransPennine Express services between Newcastle/Manchester Victoria and Liverpool and between Manchester (Airport) and Scotland (via Chat Moss, Lowton and Wigan). From December 2014, with completion of electrification (see below) the two routes between Manchester and Liverpool will have much the same frequency of service.

On the original route, a new (May 2014) hourly First TransPennine Express non-stop service runs between Manchester Victoria and Liverpool (from/to) Newcastle), an hourly fast service is operated by Northern Rail, from Liverpool to Manchester, usually calling at Wavertree Technology Park, St Helens Junction, Newton-le-Willows and Manchester Oxford Road, and continuing via Manchester Piccadilly to Manchester Airport. Northern also operates an hourly service calling at all stations from Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Victoria. This is supplemented by an additional all-stations service between Liverpool and Earlestown, which continues to Warrington Bank Quay.

Between Warrington Bank Quay, Earlestown and Manchester Piccadilly, there are additional services (at least one per hour) operated by Transport for Wales, which originate from Chester and the North Wales Coast Line.

Electrification

[edit]In 2009, electrification at 25 kV AC was announced. The section between Manchester and Newton, including the Chat Moss section, was completed in 2013; the line onwards to Liverpool opened on 5 March 2015.[95]

Ordsall Chord

[edit]The historic passenger railway station of Manchester Liverpool Road is a Grade I Listed building, and was threatened by the Northern Hub plan. This included the construction of the Ordsall Chord to provide direct access between Victoria and Piccadilly, in turn cutting off access from Liverpool Road. The Science & Industry Museum, that is based at the former station premises, had initially objected to the scheme and an inquiry was set up in 2014 to investigate the potential damage to the historic structure.[96] The chord opened in November 2017 without any damage to the original Liverpool Road station structures.[97]

Stations

[edit]

All stations opened on 15 September 1830, unless noted. Stations still operational in bold.

- Liverpool Lime Street (work started on Edge Hill – Lime Street tunnel 23 May 1832; opened 15 August 1836).

- Crown Street (original Liverpool terminus, replaced by Lime Street).

- Edge Hill (The first Edge Hill station was opened in 1830.[98] It was in the deep Cavendish Cutting at the heads of the Crown Street tunnel and the freight only Wapping Tunnel. After the Lime Street tunnel was bored in 1836, the original Edge Hill station was abandoned and relocated north, still inside the Edge Hill junction, to its present location at the head of the original Lime Street tunnel.[98] Edge Hill junction was the site of the locomotive works.)

- Wavertree Lane (closed 15 August 1836)

- Wavertree Technology Park (opened 13 August 2000)

- Broad Green

- Roby

- Huyton

- Huyton Quarry (closed 15 September 1958)

- Whiston (Opened 10 September 1990)[99]

- Rainhill

- Lea Green (closed 7 March 1955 and re-opened with a completely new station on 17 September 2000)

- St Helens Junction (opened between 1833 and 1837; junction with the St Helens and Runcorn Gap Railway)

- Collins Green (closed 2 April 1951)

- Earlestown (built in 1831 by the Warrington and Newton Railway company; originally named Newton Junction; renamed after 1837)

- Newton-le-Willows (originally named Newton Bridge; renamed after Newton Junction was renamed Earlestown)

- Parkside 1st (closed 1839)

- Parkside 2nd (the line from Parkside to Wigan was opened on 3 September 1832[100]) (closed 1 May 1878)

- Kenyon Junction (at the junction with the Kenyon and Leigh Junction Railway and from that, the Bolton and Leigh Railway; closed 2 January 1961 and the Tyldesley Loopline; closed 5 May 1969)

- Glazebury and Bury Lane (closed 7 July 1958)

- Flow Moss (closed October 1842)

- Astley (closed 2 May 1956)

- Lamb's Cottage (closed October 1842)

- Barton Moss 1st (closed 1 May 1862)

- Barton Moss 2nd (closed 23 September 1929)

- Patricroft

- Eccles

- Weaste (closed 19 October 1942; site destroyed when M602 road built)

- Seedley (closed 2 January 1956; site destroyed when M602 road built)

- Cross Lane (closed 15 August 1949; site destroyed when M602 road built)

- Ordsall Lane (work on extension of line to Manchester Victoria started 30 July 1842 and the extension opened on 4 May 1844; station closed 4 February 1957)

- Liverpool Road (original Manchester terminus, closed 4 May 1844)

- Manchester Exchange (opened 30 June 1884, closed 5 May 1969)

- Manchester Victoria (opened 1 January 1844)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Stockton and Darlington Railway opened in 1825, but sections of this line employed cable haulage, and only the coal trains were hauled by locomotives. The Canterbury and Whitstable Railway, opened in May 1830, was also mostly cable hauled. Horse-drawn traffic, including passenger services, used the railway upon payment of a toll.

- ^ The additional half-inch was to prevent the flanges wearing against the inside edge of the conical rails.[91]

- ^ The Killingworth Colliery railway was also 4ft 8in gauge.[91]

- ^ A History and Description of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. T. Taylor, 1832.

- ^ Arthur Freeling. Freeling's Grand Junction Railway Companion. Whittaker, 1838

- ^ James Cornish. The Grand Junction, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Companion: Containing an Account of Birmingham, Liverpool, and Manchester. 1837.

- ^ a b c d BBC 2009.

- ^ a b Jarvis 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 107.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 11.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 11.

- ^ a b Dendy Marshall 1930, pp. 1–3.

- ^ a b Thomas 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 13.

- ^ Taylor 1988, p. 158.

- ^ John Goodchild, 'The Lake Lock Railroad', Early Railways 3, pp. 40–50

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 7.

- ^ Thomas 1980, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 50.

- ^ a b "Making the Liverpool and Manchester Railway". Science and Industry Museum. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 18.

- ^ Booth 1830, p. 9.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 22.

- ^ Thomas 1980, pp. 26–30.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 17.

- ^ a b Thomas 1980, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 23.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 19.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 20.

- ^ Jarvis 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 27.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 25.

- ^ a b Thomas 1980, p. 28.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Thomas 1980, pp. 28–29, 50.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 33.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Ferneyhough 1980, p. 32.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 39.

- ^ "Wapping and Crown Street Tunnels". Engineering Timelines. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 42.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 44.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 46,48.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 47.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 48.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 64.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 49.

- ^ Hartwell 2002, p. 15.

- ^ a b Ferneyhough 1980, p. 33.

- ^ "Fishbelly Rails on stone sleepers - Original track on the Liverpool Manchester Bolton Leigh Railway of 1830". Lancashire Mining Museum. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "How the railways made Manchester". Manchester Evening News. 18 January 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "The opening of the Liverpool and Manchester railway, 1830". London Gazette. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 44.

- ^ Hendrickson, III, Kenneth E. (25 November 2014). The Encyclopedia of the Industrial Revolution in World History. Vol. 3. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, pp. 48, 55.

- ^ "Gauging - The V/S SIC Guide to British gauging practice" (PDF). Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB). January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 70.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 73.

- ^ Anon (21 September 1830). "Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway: Melancholy accident to Mr. Huskisson (From a Manchester Paper)". The Hull Packet and Humber Mercury.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Ferneyhough 1980, p. 75.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 87.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 76.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Thomas 1980, pp. 91, 93.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 186.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 86.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 195.

- ^ Wolmar 2007, p. 55.

- ^ a b Jackman 2014, p. 526.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 207.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 138.

- ^ Carlson 1969, pp. 11–16.

- ^ Thomas 1980, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Thomas 1980, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 116.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 119.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 104-105.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, pp. 132, 137.

- ^ Ferneyhough 1980, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1980, p. 216.

- ^ a b c d Thomas 1980, p. 217.

- ^ a b Thomas 1980, p. 219.

- ^ Wolmar 2007, p. 49.

- ^ Wolmar 2007, p. 49-50.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 220.

- ^ Thomas 1980, p. 221.

- ^ a b Ferneyhough (1980), ifc; pp=81–82.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1980, p. 59.

- ^ Thomas 1980, pp. 208–215.

- ^ Adams 1879, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Adams 1879, p. 11.

- ^ "Better rail services become a reality between Liverpool Lime Street and Manchester Airport station". Network Rail Media Centre. Network Rail. 5 March 2015. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ Merrick, Jay (11 May 2014). "'Oldest railway station in the world' threatened by Network Rail plans". The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Elledge, John (16 November 2017). "Network Rail let me have a play on Manchester's new rail bridge. Here's what I learned". CityMetric. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ a b Biddle, Gordon (2003). "Liverpool". Britain's Historic Railway Buildings. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 524–525. ISBN 978-0-19-866247-1.

- ^ "THE 8D ASSOCIATION – The L & M". 8dassociation.btck.co.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Marshall 1969, p. 66

- Adams, Charles Frances (1879). Notes on Railroad Accidents. New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons.

- Allsop, Scott (2016). 366 Days: Compelling Stories From World History. L & E Books. ISBN 978-0-995-68091-3.

- "Manchester to Liverpool: the first inter-city railway". BBC News Local Manchester. 23 July 2009. Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Booth, Henry (1830). An Account of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Liverpool: Wales and Baines. OCLC 30937. OL 16085034W.

- Carlson, Robert (1969). The Liverpool and Manchester Railway Project 1821–1831. Newton Abbot, UK: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4646-6.

- Dendy Marshall, C. F. (1930). Centenary History of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (1st ed.). National Archives, Kew, UK: Locomotive Publishing Company.

- Donaghy, Thomas J. (1972). Liverpool & Manchester Railway operations, 1831-1845. Newton Abbot, Devon: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5705-0.

- Ferneyhough, Frank (1980). Liverpool and Manchester Railway 1830–1980. Clerkenwell Green, UK: Robert Hale Limited. ISBN 0709-18137-X.

- Garfield, Simon (2002). The Last Journey of William Huskisson: The Day the Railway Came of Age. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-21048-1.

- Hartwell, Clare (2002). Manchester. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09666-8.

- Jackman, W. T. (2014) [1916]. The Development of Transportation in Modern England (Reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-68182-8.

- Jarvis, Adrian (2007). George Stephenson. Princes Risborough, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7478-0605-9. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- Marshall, John (1969). The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, volume 1. Newton Abbot, UK: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4352-1.

- Ransom, P. J. G. (1990). The Victorian Railway and How It Evolved. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-98083-8.

- Taylor, W. D. (1988). Mastering Economic and Social History. Macmillan Education UK. ISBN 978-0-333-36804-6.

- Thomas, R. H. G. (1980). The Liverpool & Manchester Railway. London: Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-0537-6.

- Williams, Frederick S. (1852/1883/1888). Our Iron Roads.

- Wolmar, Christian (2007). Fire & Steam: A New History of the Railways in Britain. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-630-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Cornish, James (1837). Cornish's Grand Junction, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Companion.

- Kirwan, Joseph (1831). A Descriptive and Historical Account of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

- Stephenson, Robert; Locke, Joseph (1831). Observations on the Comparative merits of locomotive and fixed engines as applied to railways.

- Vignoles, Charles Blacker (1835). Two reports addressed to the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Company. Printed by Wales and Raines.

LIverpool Manchester railway.

- Walker, James Scott (1829). Liverpool and Manchester Railway: Report to the Directors on the comparative merits of loco-motives and fixed engines as a moving power (2 ed.). London: John and Arthur Arch. OCLC 18209257.

- Whishaw, Francis (1842). The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated (2nd ed.). London: John Weale. pp. 186–217. OCLC 833076248.

External links

[edit]- 1830s colour print of interior of station

- Liverpool History Online

- L&MR History at Newton-le-Willows

- Manchester to Parkside (British Railways in the 1960s Sectional Appendix Extract; via the Internet Archive)

- Parkside to Liverpool (British Railways in the 1960s Sectional Appendix Extract; via the Internet Archive)

- The line featured in a short story by Arthur Conan Doyle called "The Lost Special". One radio adaptation was made on an episode of the CBS Radio series Suspense, starring Orson Welles.