Lovćen

| Lovćen | |

|---|---|

| Ловћен | |

Štirovnik, the highest peak of Lovćen | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,749 m (5,738 ft) |

| Coordinates | 42°23′57″N 18°49′06″E / 42.3991°N 18.8184°E |

| Geography | |

| Location | Montenegro |

Lovćen (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Ловћен, pronounced [lôːftɕen]) is a mountain and national park in southwestern Montenegro. It is the inspiration behind the names Montenegro and Crna Gora, both of which mean 'Black Mountain' and refer to the appearance of Mount Lovćen when covered in dense forests.[1] The name Crna Gora was first mentioned in a charter issued by Stefan Milutin in 1276[1] and was used for several regions across medieval Serbian lands, including Skopska Crna Gora and Užička Crna Gora.

Mount Lovćen rises from the borders of the Adriatic basin, closing the long and twisting bays of Boka Kotorska and making the hinterland to the coastal town of Kotor. The mountain has two imposing peaks, Štirovnik; 1,749 m (5,738 ft) and Jezerski vrh; 1,657 m (5,436 ft).

The mountain slopes are rocky, with numerous fissures, pits and deep depressions giving its scenery a specific look. This is a karst landscape carved from limestone and dolomite.[2] Lovćen stands on the border between two completely different natural wholes, the sea and the mainland, and so it is under the influence of both climates. The specific connection of the life conditions has caused the development of the different biological systems. There are 1,158 plant species on Lovćen, four of which are endemic.[citation needed]

National park

[edit]The national park encompasses the central and the highest part of the mountain massif and covers an area of 62.20 km2 (24.02 sq mi). It was proclaimed a national park in 1952. Besides Lovćen's natural features, the significant historical, cultural and architectural heritage of the area are protected by the national park.

The area has numerous elements of national construction. The old houses and village guvna are authentic as well as the cottages in katuns, summer settlements of cattlebreeders.

A particular architectural relic worth mentioning is the road, winding uphill from Kotor to the village of Njeguši, the birthplace of Montenegro's royal family, the House of Petrović.

World War I

[edit]Upon the outbreak of World War I, Montenegro was the first nation to come to Serbia's aid, and Nicholas I of Montenegro ordered his army, on August 8, 1914, to commence operations against the Austro-Hungarian naval base in the Bay of Kotor, the Austro-Hungarian Kriegsmarine's southernmost base in the Adriatic. It was just across the border from Mount Lovćen where the army had placed several batteries of artillery, and on the same day, Montenegrin guns commenced firing on Austro-Hungarian fortifications. The forts of Kotor and the old armoured cruiser SMS Kaiser Karl VI returned the fire, aided by reconnaissance from navy seaplanes. However, on September 13, Austrian-Hungarian reinforcements arrived from Pola, in the form of three active pre-dreadnought battleships, the SMS Monarch, SMS Wien, and SMS Budapest. They outgunned the Montenegrins, who nevertheless put up a fight for several weeks, with artillery duels almost daily.

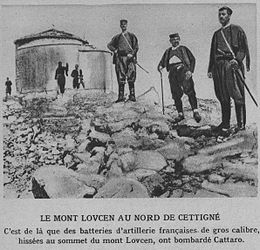

With the entry of France into the war, the French realised that the capture of Kotor might be beneficial to their own navy and so landed an artillery detachment of four 15 cm (5.9 in) and four 12 cm (4.7 in) naval guns under the command of Capitaine de frégate Grellier, at Antivari, on September 18–19. It took Grellier a month to move his guns inland but eventually his batteries were set up and positioned in fortifications on the south side of Mount Lovćen.

On October 19, the French guns opened fire. The Austro-Hungarians called for reinforcements and on October 21, Admiral Anton Haus despatched the modern battleship SMS Radetzky. With a broadside of four 30.5 cm (12.0 in) guns and four 24 cm (9.4 in) guns, the Radetzky would tip the balance. Naval seaplanes had been busy taking photographs and mapping accurate positions, and at 16:27, on October 22, the battleships all opened fire. Radetzky made a number of direct hits on the guns and fortified positions on the mountain and on October 24, one of the French 12 cm (4.7 in) guns was completely knocked out.

On October 26, the Radetzky opened fire before sunrise, catching the French and Montenegrins offguard, and a number of batteries and fortifications were destroyed in heavy bombardment, including another French 12 cm (4.7 in) gun. By 10:00, Allied firing from Mount Lovćen had ceased. The following day the Radetzky repositioned closer to the shore and blasted the Allied positions further. Grellier conceded defeat and pulled out his remaining saveable guns. Likewise, the Montenegrins abandoned their fortifications. By November, the French High Command decided to give up its campaign to neutralize and capture Cattaro, and the Radetzky returned to Pola on December 16.[3]

In early January 1916, the Austro-Hungarian army launched an offensive into Montenegro, and the battleship Budapest was again used to assist the troops against Lovćen's renewed defences to such good effect that on the 10th, the Austro-Hungarian troops took the Lovćen Pass and the adjacent heights, where the French guns had previously been. The bombardment of Mount Lovćen played a decisive role in breaking the morale of the defenders of the mountain, and the Montenegrins requested an armistice two days later.[3]

Mausoleum

[edit]The biggest and most important monument of Lovćen national park is Petar Petrović Njegoš's Mausoleum constructed in 1971. The location for his burial place and the mausoleum at the summit of Jezerski vrh was chosen by Njegoš himself as his last wish.

See also

[edit]- Lovćenac, a village in the Vojvodina named after the mountain by an influx of Montenegrins

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Montenegro History – Part I". visit-montenegro.com. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "The Panoramic Mausoleum and Karst Landscape of Lovcen National Park". 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b Noppen, Ryan & Wright, Paul, Austro-Hungarian Battleships 1914-18, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2012, pps:28-30. ISBN 978-1-84908-688-2