Musket Wars

| The Musket Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Various Māori tribes | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Up to 40,000 Māori 30,000 enslaved or forced to migrate 300 Moriori deaths, 1700 Moriori enslaved | |||||||

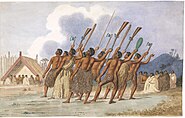

The Musket Wars were a series of as many as 3,000 battles and raids fought throughout New Zealand (including the Chatham Islands) among Māori between 1806 and 1845,[1] after Māori first obtained muskets and then engaged in an intertribal arms race in order to gain territory or seek revenge for past defeats.[2] The battles resulted in the deaths of between 20,000 and 40,000 people and the enslavement of tens of thousands of Māori and significantly altered the rohe, or tribal territorial boundaries, before the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.[3][4] The Musket Wars reached their peak in the 1830s,[5] with smaller conflicts between iwi continuing until the mid-1840s; some historians argue the New Zealand Wars were (commencing with the Wairau Affray in 1843 and Flagstaff War in 1845) a continuation of the Musket Wars.[6] The increased use of muskets in intertribal warfare led to changes in the design of pā fortifications, which later benefited Māori when engaged in battles with colonial forces during the New Zealand Wars.[6]

Ngāpuhi chief Hongi Hika in 1818 used newly acquired muskets to launch devastating raids from his Northland base into the Bay of Plenty, where local Māori were still relying on traditional weapons of wood and stone. In the following years he launched equally successful raids on iwi in Auckland, Thames, Waikato and Lake Rotorua,[3] taking large numbers of his enemies as slaves, who were put to work cultivating and dressing flax to trade with Europeans for more muskets. His success prompted other iwi to procure firearms in order to mount effective methods of defence and deterrence and the spiral of violence peaked in 1832 and 1833, by which time it had spread to all parts of the country except the inland area of the North Island later known as the King Country and remote bays and valleys of Fiordland in the South Island. In 1835, the fighting went offshore as members of Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama invaded and murdered the Moriori of Rēkohu in a genocide.

With as many as 40,000 killed over a 40-year period, the death toll of the Musket Wars was absolutely unprecedented. Historian Michael King suggested the term "holocaust" could be applied to the period;[7] another historian, Angela Ballara, has questioned the validity of the term "musket wars", suggesting the conflict was no more than a continuation of Māori tikanga (custom), but more destructive because of the widespread use of firearms.[8] The wars have been described as an example of the "fatal impact" of indigenous contact with Europeans.[8]

Origin and escalation of warfare

[edit]Māori began acquiring European muskets in the early 19th century from Sydney-based flax and timber merchants. Because they had never had projectile weapons, they initially sought guns for hunting. Their first known use in intertribal fighting was in the 1807 battle of Moremonui between Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Whātua in Northland near present-day Dargaville. Although they had some muskets, Ngāpuhi warriors struggled to load and reload them quickly enough and were defeated by an enemy armed only with traditional weapons—the clubs and blades known as patu and taiaha. However, soon after, members of the Ngāti Korokoro hapū of Ngāpuhi suffered severe losses in a raid on the Kai Tutae hapu despite outnumbering their foe ten to one, because the Kai Tutae were equipped with muskets.[7]

Under Hongi Hika's command, Ngāpuhi began amassing muskets and from about 1818 began launching effective raids on hapu throughout the North Island against whom they had grievances. Rather than occupy territory in areas where they defeated their enemy, they seized taonga (treasures) and slaves, whom they put to work to grow and prepare more crops—chiefly flax and potatoes—as well as raise pigs to trade for even more weapons. A flourishing trade in the smoked heads of slain enemies and slaves also developed. The custom of utu, or reciprocation, led to a growing series of reprisals as other iwi realised the benefits of muskets for warfare, prompting an arms race among warring groups.[7] In 1821, Hongi Hika travelled to England with missionary Thomas Kendall and in Sydney on his return voyage traded the gifts which he had obtained in England for between 300 and 500 muskets, which he then used to launch even more devastating raids, with even bigger armies, against iwi from the Auckland region to Rotorua.[7][8]

Use of the musket by Māori

[edit]The last of the non-musket wars, the 1807 Battle of Hingakaka, was fought between two opposing Māori alliances near modern Te Awamutu, with an estimated 16,000 warriors involved,[9] although as late as about 1815, some conflicts were still being fought with traditional weapons. The musket slowly put an end to the traditional combat of Māori warfare using mainly hand weapons and increased the importance of coordinated group manoeuvre. One-on-one fights such as Pōtatau Te Wherowhero's at the battle of Okoki in 1821 became rare.

Initially, the musket was used as a shock weapon, enabling traditional and iron weapons to be used effectively against a demoralised foe. But by the 1830s equally well-armed taua engaged each other with varying degrees of success. Māori learnt most of their musket technology from the various Pākehā Māori who lived in the Bay of Islands and Hokianga area. Some of these men were skilled sailors who were well-experienced in using muskets in battles at sea. Māori customised their muskets; for example, some enlarged the touch holes, which, while reducing muzzle velocity, increased the rate of fire.

Quality of muskets

[edit]Most muskets sold were low quality, short barrel trade muskets made cheaply in Birmingham with inferior steel and less precision in the action. Māori often favoured the tupara (two-barrel) shotguns loaded with musket balls, as they could fire twice before reloading. In some battles, women were used to reloading muskets while the men kept fighting. Later this presented a problem for the British and colonial forces during the New Zealand Wars when iwi would keep women in the pā.

Māori found it very hard to obtain muskets as the missionaries refused to trade them or sell powder or shot. The Ngāpuhi put missionaries under intense pressure to repair muskets even at times threatening them with violence. Most muskets were initially obtained while in Australia. Pākehā Māori such as Jacky Marmon were instrumental in obtaining muskets from trading ships in return for flax, timber and smoked heads.

Conflicts and consequences

[edit]The violence brought devastation for many tribes, with some wiped out as the vanquished were killed or enslaved, and tribal boundaries were completely redrawn as large swathes of territory were conquered and evacuated. Those changes greatly complicated later dealings with European settlers wishing to gain land.

Between 1821 and 1823 Hongi Hika attacked Ngāti Pāoa in Auckland, Ngāti Maru in Thames, Waikato tribes at Matakitaki, and Te Arawa at Lake Rotorua, heavily defeating them all. In 1825 he gained a major military victory over Ngāti Whātua at Kaipara north of Auckland, then pursued survivors into Waikato territory to gain revenge for Ngāpuhi's 1807 defeat. Ngāpuhi chiefs Pōmare and Te Wera Hauraki also led attacks on the East Coast, and in Hawke's Bay and the Bay of Plenty. Ngāpuhi's involvement in the musket wars began to recede in the early 1830s.[3]

Waikato tribes expelled Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha from Kāwhia in 1821, defeated Ngāti Kahungunu at Napier in 1824 and invaded Taranaki in 1826, forcing a number of tribal groups to migrate south. Waikato launched another major incursion into Taranaki in 1831–32.[3]

Te Rauparaha, meanwhile, had moved first to Taranaki and then to the Kāpiti coast and Kapiti Island, which Ngāti Toa chief Te Pēhi Kupe captured from the Muaupoko people. About 1827 Te Rauparaha began leading raids into the north of the South Island; by 1830 he had expanded his territory to include Kaikōura and Akaroa and much of the rest of the South Island.[3]

The final South Island battles took place in Southland in 1836–37 between forces of Ngāi Tahu leader Tūhawaiki and those of Ngāti Tama chief Te Puoho, who had followed a route from Golden Bay down the West Coast and across the Southern Alps.

Chatham Islands

[edit]In 1835 Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Tama and Ngāti Toa warriors hijacked a ship to take them to the Chatham Islands where they slaughtered about 10 per cent of the Moriori people and enslaved the survivors, before sparking war among themselves.[3]

Te Ihupuku Pā

[edit]The final conflict of the Musket Wars occurred in 1845. A Ngāti Tūwharetoa war party was stopped en route to an attack on the Ngā Rauru Te Ihupuku Pā in South Taranaki by British and church officials. The Anglican Bishop of New Zealand and a Major managed to talk both sides out of fighting. Ngāti Tūwharetoa fired the final shots of the Musket Wars symbolically into the air before returning to Taupō.[10]

Historiography

[edit]Historian James Belich has suggested "Potato Wars" as a more accurate name for these battles, due to the revolution the potato brought to the Māori economy.[11] Historian Angela Ballara says that new foods made some aspects of the wars different.[11] Potatoes were introduced in New Zealand in 1769[12] and they became a key staple with better food-value for weight than kūmara (sweet-potato), and easier cultivation and storage. Unlike the kūmara with their associated ritual requirements, potatoes were tillable by slaves and women and this freed up men to go to war.[3]

Belich saw this as a logistical revolution, with potatoes effectively fueling the long-range taua that made the musket wars different from any fighting that had come before. Slaves captured in the raids were put to work tending potato patches, freeing up labour to create even larger taua. The duration of the raids was also longer by the 1820s; it became common for warriors to be away for up to a year because it was easier to grow a series of potato crops.

In popular culture

[edit]The music video of "Kai Tangata" from New Zealand thrash metal band Alien Weaponry dramatically portrays part of the conflict that ensued with introduction of the muskets.[13]

The Convert is a film set amid the conflict.[14]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Crosby 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Bohan, Edmund (2005). Climates of War: New Zealand Conflict 1859–69. Christchurch: Hazard Press. p. 32. ISBN 9781877270963.

- ^ a b c d e f g Keane, Basil (2012). "Musket wars". Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Sinclair, Keith (2000). A History of New Zealand (2000 ed.). Auckland: Penguin. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-14-029875-8.

- ^ Crosby 1999, p. 23.

- ^ a b O'Malley 2019, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Michael King (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books. pp. 131–139. ISBN 978-0-14-301867-4.

- ^ a b c Watters, Steve (2015). "Musket wars". New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Tainui. Leslie G. Kelly. pp. 287–296. Cadsonbury. 2002

- ^ "Season 2 Ep 8: The Musket Wars". Radio New Zealand. 17 August 2022.

- ^ a b Overview – Musket Wars, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated 15 October 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Potato history, Spread of the potato Archived 11 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Eu-Sol, (European Commission) Updated 15 September. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ "ALIEN WEAPONRY – Kai Tangata (Official Video)". Napalm Records. 12 May 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ Frater, Patrick; Yossman, K.J. (6 May 2022). "New Zealand Epic 'The Convert' to Star Guy Pearce, Te Kohe Tuhaka, Launch at Cannes Market". Variety. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- "The Musket Wars". New Zealand History – Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- Crosby, Ron (1999). The Musket Wars – A History of Inter-Iwi Conflict 1806–45. Auckland: A.H. Reed. ISBN 0790006774.

- Ballara, Angela (2003). Taua: Musket Wars, Land Wars or tikanga? Warfare in Maori society in the early nineteenth century. Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 9780143018896.

- McKinnon, Malcolm (1997). Bateman New Zealand historical atlas: Ko papatuanuku e takoto nei. David Bateman in association with Historical Branch, Department of Internal Affairs (New Zealand). ISBN 1869533356.

- Belich, James, The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict. Auckland, N.Z., Penguin, 1986

- Bentley, Trevor, Cannibal Jack, Penguin, Auckland, 2010

- Best, Elsdon, Te Pa Maori, Government Printer, Wellington, 1975 (reprint)

- Carleton, Hugh, The Life of Henry Williams, Archdeacon of Waimate (1874), Auckland NZ. Online available from Early New Zealand Books (ENZB).

- Fitzgerald, Caroline, Te Wiremu – Henry Williams: Early Years in the North, Huia Publishers, New Zealand, 2011 ISBN 978-1-86969-439-5

- Moon, Paul, This Horrid Practice, The Myth and Reality of Traditional Maori Cannibalism. Penguin, Auckland, 2008 ISBN 978-0-14-300671-8

- Moon, Paul, A Savage Country. The untold story of New Zealand in the 1820s Penguin, 2012 ISBN 978-0-14356-738-7

- Rogers, Lawrence M. (editor) (1961) – The Early Journals of Henry Williams 1826 to 1840. Christchurch : Pegasus Press. online available at New Zealand Electronic Text Centre (NZETC) (2011-06-27)

- O'Malley, Vincent (2019). The New Zealand Wars Ngā Pakanga O Aotearoa. Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 9781988587011.

- Ryan T and Parham B, The colonial NZ Wars", Grantham House, 2002

- Waitangi Tribunal, Te Raupatu o Tauranga Moana – Report on Tauranga Confiscation Claims, Waitangi Tribunal Website, 2004

- Wright, Matthew, Guns & Utu: A short history of the Musket Wars (2012), Penguin, ISBN 9780143565659

External links

[edit]- "TAURANGA MAORI AND THE CROWN, 1840–64", from www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz

- Musket Wars discussion essay, for NCEA level 3

- Map of iwi movements in the 1820s

- Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century by S Percy Smith (1910, revised edition)