New Brunswick, New Jersey

New Brunswick, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

Skyline of New Brunswick | |

| Nickname(s): Hub City, Healthcare City | |

Location of New Brunswick in Middlesex County highlighted in red (left). Inset map: Location of Middlesex County in New Jersey highlighted in orange (right). | |

Census Bureau map of New Brunswick, New Jersey | |

Location in Middlesex County Location in New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 40°29′12″N 74°26′40″W / 40.486678°N 74.444414°W[1][2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Middlesex |

| Established | December 30, 1730 |

| Incorporated | September 1, 1784 |

| Named for | Braunschweig, Germany, or King George II of Great Britain |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (mayor–council) |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | James M. Cahill (D, term ends December 31, 2026)[3][4] |

| • Administrator | Michael Drulis[5][6] |

| • Municipal clerk | Leslie Zeledón[5][7] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.75 sq mi (14.90 km2) |

| • Land | 5.23 sq mi (13.55 km2) |

| • Water | 0.52 sq mi (1.35 km2) 9.06% |

| • Rank | 264th of 565 in state 14th of 25 in county[1] |

| Elevation | 62 ft (19 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 55,266 |

| • Estimate | 55,846 |

| • Rank | 32nd of 565 in state 6th of 25 in county[14] |

| • Density | 10,561.1/sq mi (4,077.7/km2) |

| • Rank | 719th in country (as of 2023)[15] 37th of 565 in state 2nd of 25 in county[14] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Codes | |

| Area code(s) | 732/848 and 908[18] |

| FIPS code | 3402351210[1][19][20] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885318[1][21] |

| Website | www |

| New Brunswick is the county seat for Middlesex County. | |

If I had to fall I wish it had been on the sidewalks of New York, not the sidewalks of New Brunswick, N.J.

— Alfred E. Smith to Lew Dockstader in December 1923 on Dockstader's fall at what is now the State Theater.[22]

New Brunswick is a city in and the county seat of Middlesex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[23] A regional commercial hub for central New Jersey, the city is both a college town (the home of Rutgers University–New Brunswick, the state's largest university) and a commuter town for residents commuting to New York City within the New York metropolitan area.[24] New Brunswick is on the Northeast Corridor rail line, 27 miles (43 km) southwest of Manhattan. The city is located on the southern banks of the Raritan River in the heart of the Raritan Valley region.

As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 55,266,[11][12] an increase of 85 (+0.2%) from the 2010 census count of 55,181,[25][26] which in turn reflected an increase of 6,608 (+13.6%) from the 48,573 counted in the 2000 census.[27] The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated a population of 55,846 for 2023,[13] making it the 719th-most populous municipality in the nation.[15] Due to the concentration of medical facilities in the area, including Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital and medical school, and Saint Peter's University Hospital, New Brunswick is known as both the Hub City and the Healthcare City.[28][29] The corporate headquarters and production facilities of several global pharmaceutical companies are situated in the city, including Johnson & Johnson and Bristol Myers Squibb. New Brunswick has evolved into a major center for the sciences, arts, and cultural activities. Downtown New Brunswick is developing a growing skyline, filling in with new high-rise towers.

New Brunswick is noted for its ethnic diversity. At one time, one-quarter of the Hungarian population of New Jersey resided in the city, and in the 1930s one out of three city residents was Hungarian.[30] The Hungarian community continues as a cohesive community, with the 3,200 Hungarian residents accounting for 8% of the population of New Brunswick in 1992.[31] Growing Asian and Hispanic communities have developed around French Street near Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The area around present-day New Brunswick was first inhabited by the Lenape Native Americans, whose Minisink Trail intersected the Raritan River and followed a route that would be taken by later colonial roads.[32] The first European settlement at the site of New Brunswick was made in 1681. The settlement here was called Prigmore's Swamp (1681–1697), then known as Inian's Ferry (1691–1714).[33] In 1714, the settlement was given the name New Brunswick, after the city of Braunschweig (Brunswick in Low German), in the state of Lower Saxony, now located in Germany. Braunschweig was an influential and powerful city in the Hanseatic League and was an administrative seat for the Duchy of Hanover. Shortly after the first settlement of New Brunswick in colonial New Jersey, George, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Elector of Hanover, became King George I of Great Britain. Alternatively, the city gets its name from King George II of Great Britain, the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg.[34][35]

Colonial and Early American periods

[edit]Centrally located between New York City and Philadelphia along an early thoroughfare known as the King's Highway and situated along the Raritan River, New Brunswick became an important hub for Colonial travelers and traders. New Brunswick was incorporated as a town in 1736 and chartered as a city in 1784.[36] It was incorporated into a town in 1798 as part of the Township Act of 1798. It was occupied by the British in the winter of 1776–1777 during the Revolutionary War.[37]

The Declaration of Independence received one of its first public readings, by Colonel John Neilson in New Brunswick on July 9, 1776, in the days following its promulgation by the Continental Congress.[38][39][40] A bronze statue marking the event was dedicated on July 9, 2017, in Monument Square, in front of the Heldrich Hotel.[41]

The Trustees of Queen's College (now Rutgers University), founded in 1766, voted by a margin of ten to seven in 1771 to locate the young college in New Brunswick, selecting the city over Hackensack, in Bergen County, New Jersey.[42] Classes began in 1771 with one instructor, one sophomore, Matthew Leydt, and several freshmen at a tavern called the 'Sign of the Red Lion' on the corner of Albany and Neilson Streets (now the grounds of the Johnson & Johnson corporate headquarters); Leydt would become the university's first graduate in 1774 when he was the only member of the graduating class.[43] The Sign of the Red Lion was purchased on behalf of Queens College in 1771, and later sold to the estate of Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh in 1791.[44] Classes were held through the American Revolution in various taverns and boarding houses, and at a building known as College Hall on George Street, until Old Queens was completed and opened in 1811.[45][46] It remains the oldest building on the Rutgers University campus.[47] The Queen's College Grammar School (now Rutgers Preparatory School) was established also in 1766, and shared facilities with the college until 1830, when it located in a building (now known as Alexander Johnston Hall) across College Avenue from Old Queens.[48] After Rutgers University became the state university of New Jersey in 1945,[49] the Trustees of Rutgers divested itself of Rutgers Preparatory School, which relocated in 1957 to an estate purchased from Colgate-Palmolive in Franklin Township in neighboring Somerset County.[50]

The New Brunswick Theological Seminary, founded in 1784 in New York, moved to New Brunswick in 1810, sharing its quarters with the fledgling Queen's College. (Queen's closed from 1810 to 1825 due to financial problems, and reopened in 1825 as Rutgers College.)[51] The Seminary, due to overcrowding and differences over the mission of Rutgers College as a secular institution, moved to a tract of land covering 7 acres (2.8 ha) located less than 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) to the west, which it still occupies, although the land is now in the middle of Rutgers University's College Avenue Campus.[52]

New Brunswick was formed by royal charter on December 30, 1730, within other townships in Middlesex and Somerset counties and was reformed by royal charter with the same boundaries on February 12, 1763, at which time it was divided into north and south wards. New Brunswick was incorporated as a city by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on September 1, 1784.[36]

- Old Queens, the oldest building at Rutgers University

- Building the Streetcar line, c. 1885

- Albany Street Bridge, 1903

- Aerial view of New Brunswick, 1910

African-American community

[edit]Slavery in New Brunswick

[edit]The existence of an African American community in New Brunswick dates back to the 18th century, when racial slavery was a part of life in the city and the surrounding area. Local slaveholders routinely bought and sold African American children, women, and men in New Brunswick in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century. In this period, the Market-House was the center of commercial life in the city. It was located at the corner of Hiram Street and Queen Street (now Neilson Street) adjacent to the Raritan Wharf. The site was a place where residents of New Brunswick sold and traded their goods which made it an integral part of the city's economy. The Market-House also served as a site for regular slave auctions and sales.[53]: 101

By the late-eighteenth century, New Brunswick became a hub for newspaper production and distribution. The Fredonian, a popular newspaper, was located less than a block away from the aforementioned Market-House and helped facilitate commercial transactions. A prominent part of the local newspapers were sections dedicated to private owners who would advertise their slaves for sale. The trend of advertising slave sales in newspapers shows that the New Brunswick residents typically preferred selling and buying slaves privately and individually rather than in large groups.[53]: 103 The majority of individual advertisements were for female slaves, and their average age at the time of the sale was 20 years old, which was considered the prime age for childbearing. Slave owners would get the most profit from the women who fit into this category because these women had the potential to reproduce another generation of enslaved workers. Additionally, in the urban environment of New Brunswick, there was a high demand for domestic labor, and female workers were preferred for cooking and housework tasks.[53]: 107

The New Jersey Legislature passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1804.[54] Under the provisions of this law, children born to enslaved women after July 4, 1804, would serve their master for a term of 21 years (for girls) or a term of 25 years (for boys), and after this term, they would gain their freedom. However, all individuals who were enslaved before July 4, 1804, would continue to be slaves for life and would never attain freedom under this law. New Brunswick continued to be home to enslaved African Americans alongside a growing community of free people of color. The 1810 United States Census listed 53 free Blacks and 164 slaves in New Brunswick.[55]

African American spaces and institutions in the early 19th century

[edit]By the 1810s, some free African Americans lived in a section of the city called Halfpenny Town, which was located along the Raritan River by the east side of the city, near Queen (now Neilson) Street. Halfpenny Town was a place populated by free blacks as well as poorer whites who did not own slaves. This place was known as a social gathering for free blacks that was not completely influenced by white scrutiny and allowed free blacks to socialize among themselves. This does not mean that it was free from white eyes and was still under the negative effects of the slavery era.[53]: 99 In the early decades of the nineteenth century, White and either free or enslaved African Americans shared many of the same spaces in New Brunswick, particularly places of worship. The First Presbyterian Church, Christ Church, and First Reformed Church were popular among both Whites and Blacks, and New Brunswick was notable for its lack of spaces where African Americans could congregate exclusively. Most of the time Black congregants of these churches were under the surveillance of Whites.[53]: 113 That was the case until the creation of the African Association of New Brunswick in 1817.[53]: 114–115

Both free and enslaved African Americans were active in the establishment of the African Association of New Brunswick, whose meetings were first held in 1817.[53]: 112 The African Association of New Brunswick held a meeting every month, mostly in the homes of free blacks. Sometimes these meetings were held at the First Presbyterian Church. Originally intended to provide financial support for the African School of New Brunswick, the African Association grew into a space where blacks could congregate and share ideas on a variety of topics such as religion, abolition and colonization. Slaves were required to obtain a pass from their owner in order to attend these meetings. The African Association worked closely with Whites and was generally favored amongst White residents who believed it would bring more racial peace and harmony to New Brunswick.[53]: 114–115

The African Association of New Brunswick established the African School in 1822. The African School was first hosted in the home of Caesar Rappleyea in 1823.[53]: 114 The school was located on the upper end of Church Street in the downtown area of New Brunswick about two blocks away from the jail that held escaped slaves. Both free and enslaved Blacks were welcome to be members of the School.[53]: 116 Reverend Huntington (pastor of the First Presbyterian Church) and several other prominent Whites were trustees of the African Association of New Brunswick. These trustees supported the Association which made some slave owners feel safe sending their slaves there by using a permission slip process.[53]: 115 The main belief of these White supporters was that Blacks were still unfit for American citizenship and residence, and some trustees were connected with the American Colonization Society that advocated for the migration of free African Americans to Africa. The White trustees only attended some of the meetings of the African Association, and the Association was still unprecedented as a space for both enslaved and free Blacks to get together while under minimal supervision by Whites.[53]: 116–117

The African Association appears to have disbanded after 1824. By 1827, free and enslaved Black people in the city, including Joseph and Jane Hoagland, came together to establish the Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church and purchased a plot of land on Division Street for the purpose of erecting a church building. This was the first African American church in Middlesex County. The church had approximately 30 members in its early years. The church is still in operation and is currently located at 39 Hildebrand Way. The street Hildebrand Way is named after the late Rev. Henry Alphonso Hildebrand, who was pastor of Mount Zion AME for 37 years, which is the longest appointment received by a pastor at Mount Zion AME.[56]

Records from the April 1828 census, conducted by the New Brunswick Common Council, state that New Brunswick was populated with 4,435 white residents and 374 free African Americans. The enslaved population of New Brunswick in 1828 consisted of 57 slaves who must serve for life and 127 slaves eligible for emancipation at age 21 or 25 due to the 1804 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. Free and enslaved African Americans accounted for 11% of New Brunswick's population in 1828, a relatively high percentage for New Jersey.[53]: 94 By comparison, as of the 1830 United States Census, African Americans made up approximately 6.4% of the total population of New Jersey.[57]

Jail and curfew in the 19th century

[edit]In 1824, the New Brunswick Common Council adopted a curfew for free people of color. Free African Americans were not allowed to be out after 10 pm on Saturday night. The Common Council also appointed a committee of white residents who were charged with rounding up and detaining free African Americans who appeared to be out of place according to white authorities.[53]: 98

New Brunswick became a notorious city for slave hunters, who sought to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Strategically located on the Raritan River, the city was also a vital hub for New Jersey's Underground Railroad. For runaway slaves in New Jersey, it served as a favorable route for those heading to New York and Canada. When African Americans tried to escape either to or from New Brunswick, they had a high likelihood of getting discovered and captured and sent to New Brunswick's jail, which was located on Prince Street, which by now is renamed Bayard Street.[53]: 96

Hungarian community

[edit]

New Brunswick has been described as the nation's "most Hungarian city", with Hungarian immigrants arriving in the city as early as 1888 and accounting for almost 20% of the city's population in 1915.[58] Hungarians were primarily attracted to the city by employment at Johnson & Johnson factories located in the city.[59] Hungarians settled mainly in what today is the Fifth Ward and businesses were established to serve the needs of the Hungarian community that weren't being met by mainstream businesses.[60] The immigrant population grew until the end of the immigration boom in the early 20th century.

During the Cold War, the community was revitalized by the decision to process the tens of thousands refugees who came to the United States from the failed 1956 Hungarian Revolution at Camp Kilmer, in nearby Edison.[61] Even though the Hungarian population has been largely supplanted by newer immigrants, there continues to be a Hungarian Festival in the city held on Somerset Street on the first Saturday of June each year; the 44th annual event was held in 2019.[62] Many Hungarian institutions set up by the community remain and are active in the neighborhood, including: Magyar Reformed Church, Ascension Lutheran Church, St. Ladislaus Roman Catholic Church, St. Joseph Byzantine Catholic Church, Hungarian American Athletic Club, Aprokfalva Montessori Preschool, Széchenyi Hungarian Community School & Kindergarten, Teleki Pál Scout Home, Hungarian American Foundation, Vers Hangja, Hungarian Poetry Group, Bolyai Lecture Series on Arts and Sciences, Hungarian Alumni Association, Hungarian Radio Program, Hungarian Civic Association, Committee of Hungarian Churches and Organizations of New Brunswick, and Csűrdöngölő Folk Dance Ensemble.

Several landmarks in the city also testify to its Hungarian heritage. There is a street and a park named after Lajos Kossuth, one of the leaders of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. The corner of Somerset Street and Plum Street is named Mindszenty Square where the first ever statue of Cardinal József Mindszenty was erected.[31] A stone memorial to the victims of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution stands nearby.[63]

Latino community

[edit]In the 2010 Census, about 50% of New Brunswick's population is self-identified as Hispanic, the 14th highest percentage among municipalities in New Jersey.[25][64] Since the 1960s, many of the new residents of New Brunswick have come from Latin America. Many citizens moved from Puerto Rico in the 1970s. In the 1980s, many immigrated from the Dominican Republic, and still later from Guatemala, Honduras, Ecuador and Mexico.

Demolition, revitalization, and redevelopment

[edit]

New Brunswick is one of nine cities in New Jersey designated as eligible for Urban Transit Hub Tax Credits by the state's Economic Development Authority. Developers who invest a minimum of $50 million within a half-mile of a train station are eligible for pro-rated tax credit.[65][66]

New Brunswick contains a number of examples of urban renewal in the United States. In the 1960s–1970s, the downtown area became blighted as middle class residents moved to newer suburbs surrounding the city, an example of the phenomenon known as "white flight." Beginning in 1975, Rutgers University, Johnson & Johnson and the city's government collaborated through the New Jersey Economic Development Authority to form the New Brunswick Development Company (DevCo), with the goal of revitalizing the city center and redeveloping neighborhoods considered to be blighted and dangerous (via demolition of existing buildings and construction of new ones).[67][68] Johnson & Johnson announced in 1978 that they would remain in New Brunswick and invest $50 million to build a new world headquarters building in the area between Albany Street, Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, Route 18, and George Street, requiring many old buildings and historic roads to be removed.[69] The Hiram Market area, a historic district that by the 1970s had become a mostly Puerto Rican and Dominican-American neighborhood, was demolished to build a Hyatt hotel and conference center, and upscale housing.[70] Johnson & Johnson guaranteed the investment made by Hyatt Hotels, as they were wary of building an upscale hotel in a run-down area.[citation needed]

Devco, the hospitals, and the city government have drawn ire from both historic preservationists, those opposing gentrification[71] and those concerned with eminent domain abuses and tax abatements for developers.[72]

New Brunswick is home to the main campus of Rutgers University and Johnson & Johnson, which in 1983 constructed its new headquarters in the city.[73][74][75] Both work with Devco in a public–private partnership to redevelop downtown, particularly regarding transit-oriented development.[76][77][78][79][80][81][82] Boraie Development, a real estate development firm based in New Brunswick, has developed projects using the incentives provided by Devco and the state.[citation needed]

Tallest buildings

[edit]Christ Church, originally built in 1742, was the tallest building at the time of construction.[83] A steeple was added in 1773 and replaced in 1803.[84] The six-story First Reformed Church, built in 1812, was long the city's tallest structure.[85] One of the earliest tall commercial buildings in the city was the eight-story 112.5 ft (34.29 m) National Bank of New Jersey built in 1908.[86][87] The four nine-story 125 ft (38 m) buildings of the New Brunswick Homes housing project, originally built in 1958, were demolished by implosion in 2000 and largely replaced by low-rise housing.[88][89][90]

While there are no buildings over 300 feet (91 meters), since the beginning of the new millennium, a number of high-rise residential buildings have been added to the city's skyline.[91] clustered around the New Brunswick station have joined those built in the 1960s on the city's skyline.[92][93][94][95][96] Of the 16 buildings over 150 feet (46 m), nine of them were built in the 21st century; several others are approved or proposed.

| Rank | Name | image | Height ft/m | Floors | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Gateway |  | 298 ft (91 m) | 24 | 2012 | Louis Berger Group[97][93][98][99][100] |

| 2 | New Brunswick Performing Arts Center |  | 282 ft (86 m)[a] | 22 | 2019[101] | Elkus Manfredi Architects[102][103][104][105][106] |

| 3 | One Spring Street |  | 258 ft (79 m) | 23 | 2006 | Costas Kondylis[107][93][108][109][110] |

| 4 | One Johnson and Johnson Plaza |  | 228 ft (69 m) | 16 | 1983 | Headquarters of Johnson & Johnson; |

| 5 | The Standard at New Brunswick | 225 ft (69 m) | 21 | 2020 | [115][116] | |

| 6 | Colony House |  | 246 ft (75 m) | 20 | 1962 | [93][117] |

| 7 | Skyline Tower |  | 194 ft (59 m) | 14 | 1967/2003 | [93][118][119][120] |

| 8 | Schatzman-Fricano Apartments |  | 194 ft (59 m) | 14 | 1963 | [93][121] |

| 9 | The George |  | 14 | 2013 | [122][123][120] | |

| 10 | Riverside Towers | 177 ft (54 m) | 13 | 1964 | [93][124][125] | |

| 11 | The Heldrich |  | 160 ft (50 m) | 11 | 2007 | [93][126][127] |

| 12 | Rockhoff Hall/SoCam290 |  | 160 ft (50 m) | 12 | 2005 | [93][128][129][130][131][132] |

| 13 | Aspire |  | 161 ft (49 m) | 16/17 | 2015 | Bradford Perkins[133][134][135][136][137][80] |

| 14 | The Yard[138] |  | 161 ft (49 m) | 14 | 2016[139] | Elkus/Manfredi Architects[140][141][142] |

| 15 | 410 George Street |  | 154 ft (47 m) | 11 | 1989 | Rothe-Johnson Architects[93][143] |

| 16 | University Center |  | 149 ft (45.3 m) | 12 | 1994 | [93][144][145] |

Tallest buildings under construction, approved, and proposed

[edit]| Name | Height | Floors | Status | Year (est) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB Plaza | 45 | Approved | [146] | ||

| H-3 | 42 | Proposed | 2030 | Part of the three-tower HELIX complex[147][148] | |

| 11 Spring Street | 27 | Approved | Height reduced from 30 floors to 27 in 2024[149][150] | ||

| The Liv | 23 | Approved | On the site of the Elks Club Lodge[151][152] | ||

| H-1 | 13 | Under construction | 2025 | Part of the three-tower HELIX complex[147][148] | |

| Jack & Sheryl Morris Cancer Center | 12 | Under construction | 2025 | New Jersey's first freestanding cancer hospital[153] | |

| H-2 | 11 | Approved | 2028 | NOKIA Headquarters; part of the three-tower HELIX complex[147][148] |

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 5.75 square miles (14.9 km2), including 5.23 square miles (13.5 km2) of land and 0.52 square miles (1.3 km2) of water (9.06%).[1][2] New Brunswick is on the south side of Raritan Valley along with Piscataway, Highland Park, Edison, and Franklin Township. New Brunswick lies southwest of Newark and New York City and northeast of Trenton and Philadelphia.

New Brunswick is bordered by the municipalities of Piscataway, Highland Park and Edison across the Raritan River to the north by way of the Donald and Morris Goodkind Bridges, and also by North Brunswick to the southwest, East Brunswick to the southeast, all in Middlesex County; and by Franklin Township in Somerset County.[154][155][156]

While the city does not hold elections based on a ward system it has been so divided.[157][158][159] There are several neighborhoods in the city, which include the Fifth Ward, Feaster Park, Lincoln Park,[citation needed] Raritan Gardens, and Edgebrook-Westons Mills.[157]

Climate

[edit]Under the Köppen climate classification, New Brunswick falls within either a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) if the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm is used or a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) if the −3 °C (27 °F) isotherm is used. New Brunswick has humid, hot summers and moderately cold winters with moderate to considerable rainfall throughout the year. There is no marked wet or dry season. The average seasonal (October–April) snowfall total is around 29 inches (74 cm). The average snowiest month is February, which corresponds to the annual peak in nor'easter activity.

| Climate data for New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) | 79 (26) | 88 (31) | 95 (35) | 99 (37) | 102 (39) | 106 (41) | 106 (41) | 103 (39) | 95 (35) | 83 (28) | 76 (24) | 106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 63.0 (17.2) | 63.1 (17.3) | 72.5 (22.5) | 83.9 (28.8) | 89.3 (31.8) | 93.5 (34.2) | 96.6 (35.9) | 94.4 (34.7) | 90.4 (32.4) | 82.3 (27.9) | 73.8 (23.2) | 65.1 (18.4) | 97.7 (36.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 40.3 (4.6) | 42.8 (6.0) | 50.6 (10.3) | 62.5 (16.9) | 72.1 (22.3) | 81.2 (27.3) | 86.5 (30.3) | 84.7 (29.3) | 78.4 (25.8) | 66.5 (19.2) | 55.5 (13.1) | 45.4 (7.4) | 63.9 (17.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.6 (−0.2) | 33.4 (0.8) | 40.8 (4.9) | 51.7 (10.9) | 61.3 (16.3) | 70.8 (21.6) | 76.1 (24.5) | 74.3 (23.5) | 67.4 (19.7) | 55.4 (13.0) | 45.4 (7.4) | 36.9 (2.7) | 53.8 (12.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 22.9 (−5.1) | 24.0 (−4.4) | 31.0 (−0.6) | 40.8 (4.9) | 50.6 (10.3) | 60.4 (15.8) | 65.6 (18.7) | 64.0 (17.8) | 56.5 (13.6) | 44.2 (6.8) | 35.2 (1.8) | 28.4 (−2.0) | 43.6 (6.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 6.3 (−14.3) | 8.8 (−12.9) | 16.7 (−8.5) | 28.3 (−2.1) | 36.7 (2.6) | 46.4 (8.0) | 54.9 (12.7) | 53.0 (11.7) | 42.2 (5.7) | 30.3 (−0.9) | 21.1 (−6.1) | 14.3 (−9.8) | 4.1 (−15.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −15 (−26) | −16 (−27) | 2 (−17) | 11 (−12) | 28 (−2) | 38 (3) | 45 (7) | 40 (4) | 33 (1) | 22 (−6) | 6 (−14) | −15 (−26) | −16 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.74 (95) | 2.97 (75) | 4.40 (112) | 3.89 (99) | 4.03 (102) | 4.83 (123) | 4.83 (123) | 4.66 (118) | 4.18 (106) | 4.11 (104) | 3.40 (86) | 4.49 (114) | 49.53 (1,258) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.3 (21) | 9.3 (24) | 5.2 (13) | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.51) | 0.5 (1.3) | 4.9 (12) | 29.0 (74) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.1 | 9.6 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 12.6 | 11.4 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 8.7 | 10.3 | 125.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.2 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 13.3 |

| Source: NOAA[160][161] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 5,866 | — | |

| 1850 | 10,019 | 70.8% | |

| 1860 | 11,256 | 12.3% | |

| 1870 | 15,058 | 33.8% | |

| 1880 | 17,166 | 14.0% | |

| 1890 | 18,603 | 8.4% | |

| 1900 | 20,005 | 7.5% | |

| 1910 | 23,388 | 16.9% | |

| 1920 | 32,779 | 40.2% | |

| 1930 | 34,555 | 5.4% | |

| 1940 | 33,180 | −4.0% | |

| 1950 | 38,811 | 17.0% | |

| 1960 | 40,139 | 3.4% | |

| 1970 | 41,885 | 4.3% | |

| 1980 | 41,442 | −1.1% | |

| 1990 | 41,711 | 0.6% | |

| 2000 | 48,573 | 16.5% | |

| 2010 | 55,181 | 13.6% | |

| 2020 | 55,266 | 0.2% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 55,846 | [11][13] | 1.0% |

| Population sources: 1860–1920[162] 1840–1890[163] 1850–1870[164] 1850[165] 1870[166] 1880–1890[167] 1890–1910[168] 1860–1930[169] 1940–2000[170] 2000[171][172] 2010[25][26] 2020[11][12] | |||

2010 census

[edit]The 2010 United States census counted 55,181 people, 14,119 households, and 7,751 families in the city. The population density was 10,556.4 per square mile (4,075.8/km2). There were 15,053 housing units at an average density of 2,879.7 per square mile (1,111.9/km2). The racial makeup was 45.43% (25,071) White, 16.04% (8,852) Black or African American, 0.90% (498) Native American, 7.60% (4,195) Asian, 0.03% (19) Pacific Islander, 25.59% (14,122) from other races, and 4.39% (2,424) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 49.93% (27,553) of the population.[25]

Of the 14,119 households, 31.0% had children under the age of 18; 29.2% were married couples living together; 17.5% had a female householder with no husband present and 45.1% were non-families. Of all households, 25.8% were made up of individuals and 7.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.36 and the average family size was 3.91.[25]

21.1% of the population were under the age of 18, 33.2% from 18 to 24, 28.4% from 25 to 44, 12.2% from 45 to 64, and 5.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 23.3 years. For every 100 females, the population had 105.0 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 105.3 males.[25]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $44,543 (with a margin of error of +/− $2,356) and the median family income was $44,455 (+/− $3,526). Males had a median income of $31,313 (+/− $1,265) versus $28,858 (+/− $1,771) for females. The per capita income for the borough was $16,395 (+/− $979). About 15.5% of families and 25.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.4% of those under age 18 and 16.9% of those age 65 or over.[173]

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 United States census, there were 48,573 people, 13,057 households, and 7,207 families residing in the city. The population density was 9,293.5 inhabitants per square mile (3,588.2/km2). There were 13,893 housing units at an average density of 2,658.1 per square mile (1,026.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.7% White, 24.5% African American, 1.2% Native American, 5.9% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 21.0% from other races, and 4.2% from two or more races. 39.01% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[171][172]

There were 13,057 households, of which 29.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.6% were married couples living together, 18.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.8% were non-families. 24.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.23 and the average family size was 3.69.[171][172]

20.1% of the population were under the age of 18, 34.0% from 18 to 24, 28.1% from 25 to 44, 11.3% from 45 to 64, and 6.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 24 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.8 males.[171][172]

The median household income in the city was $36,080, and the median income for a family was $38,222. Males had a median income of $25,657 versus $23,604 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,308. 27.0% of the population and 16.9% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total people living in poverty, 25.9% were under the age of 18 and 13.8% were 65 or older.[171][172]

Economy

[edit]Healthcare industry

[edit]City Hall has promoted the nickname "The Health Care City" to reflect the importance of the healthcare industry to its economy.[174] The city is home to the world headquarters of Johnson & Johnson, along with several medical teaching and research institutions.[175] Described as the first magnet secondary school program teaching directly affiliated with a teaching hospital and a medical school, New Brunswick Health Sciences Technology High School is a public high school, that operates as part of the New Brunswick Public Schools, focused on health sciences.[176]

Urban Enterprise Zone

[edit]Portions of the city are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ), one of 32 zones covering 37 municipalities statewide. New Brunswick was selected in 2004 as one of two zones added to participate in the program.[177] In addition to other benefits to encourage employment and investment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half of the 6+5⁄8% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[178] Established in December 2004, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in December 2024.[179][180]

Arts and culture

[edit]Theatre

[edit]The New Brunswick Performing Arts Center opened 2019. Three neighboring professional venues, Crossroads Theatre designed by Parsons+Fernandez-Casteleiro Architects from New York. In 1999, the Crossroads Theatre won the prestigious Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre. Crossroads is the first African American theater to receive this honor in the 33-year history of this special award category.[181] George Street Playhouse (founded in 1974)[182] and the State Theatre (constructed in 1921 for vaudeville and silent films)[183] also form the heart of the local theatre scene. Crossroad Theatre houses American Repertory Ballet and the Princeton Ballet School.[184] Rutgers University has student-run companies such as Cabaret Theatre, The Livingston Theatre Company, and College Avenue Players which perform everything from musicals to dramatic plays to sketch comedy.

Journalism

[edit]New Brunswick Today is a print and digital publication launched in 2011 by Rutgers journalism alumnus Charlie Kratovil[185] which uses the tagline "Independent news for the greater New Brunswick community". The publication has covered issues with the city's water utility among others and was featured on Full Frontal with Samantha Bee.[186]

New Jersey alt-weeklies The Aquarian Weekly[187] and NJ Indy cover music and arts in New Brunswick.[188]

Museums

[edit]New Brunswick is the site of the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (founded in 1966),[189] Albus Cavus, and the Rutgers University Geology Museum (founded in 1872).[190]

Fine arts

[edit]New Brunswick was an important center for avant-garde art in the 1950s–1970s with several artists such as Allan Kaprow, George Segal, George Brecht, Robert Whitman, Robert Watts, Lucas Samaras, Geoffrey Hendricks, Wolf Vostell and Roy Lichtenstein; some of whom taught at Rutgers University. This group of artists was sometimes referred to as the 'New Jersey School' or the 'New Brunswick School of Painting'. The YAM Festival was a venue on May 19, 1963, for actions and happenings. For more information, see Fluxus at Rutgers University.[191][192]

Music

[edit]

New Brunswick's live music scene has been the home to many original rock bands, including some which went on to national prominence such as The Smithereens and Bon Jovi.[193] Rock band Looking Glass, who had the number one hit "Brandy (You're a Fine Girl)" in 1972, developed in the New Brunswick rock scene and dedicated their debut to "the people of New Brunswick."[194]

The city is in particular a center for local punk rock and underground music.[195][196] Alternative rock, indie rock, and hardcore music have long been popular in the city's live music scene.[197] Many alternative rock bands got radio airplay thanks to Matt Pinfield who was part of the New Brunswick music scene for over 20 years at Rutgers University radio WRSU-FM and at alternative rock radio station WHTG-FM.[198] [199] [200][195][201][202][203][204][205][206][207][208][209]

Local pubs and clubs hosted many local bands, including the Court Tavern[210][211][212] and the Melody Bar during the 1980s and 1990s.[213] The city was ranked the number 4 spot to see indie bands in New Jersey.[214]

The independent record label Don Giovanni Records originally started to document the New Brunswick basement scene.[215][216] In March 2017, NJ.com wrote that "even if Asbury Park has recently returned as our state's musical nerve center, with the brick-and-mortar venues and infrastructure to prove it, New Brunswick remains as the New Jersey scene's unadulterated, pounding heart."[217] A number of well-known local bands formed in the city's live music scene, including Thursday and Ogbert the Nerd.[218][219][220][221][222] Rutgers radio station WVPH 90.3 FM "The Core" hosts indie music festival "Corefest" on campusA number of jazz organizations and jazz festivals are held in the city, including the Hub City Jazz Festival and the New Brunswick Jazz Project. The New Brunswick Jazz Project is dedicated to live jazz in the city and surrounding towns. New Brunswick also has a plethora of rappers including Trill Lik, Mello B and Amgjay and also GetBizzy Nino.

Film

[edit]New Brunswick is home to a number of film festivals, two of which are presented by the film society, the Rutgers Film Co-op/New Jersey Media Arts Center: the New Jersey Film Festival (1982) and the United States Super 8mm Film + Digital Video Festival (~1988). The Rutgers Jewish Film Festival was established 1999.[223][224] The New Lens Film Festival is an event at the Mason Gross School of the Arts.[225]

Grease trucks

[edit]

The "Grease trucks" were a group of truck-based food vendors located on the College Avenue Campus at Rutgers. They were known for serving "Fat Sandwiches," sub rolls containing fried ingredients. In 2013 the grease trucks were removed for the construction of a new Rutgers building and were moved into various other areas of the Rutgers-New Brunswick Campus.[226]

Government

[edit]New Brunswick City Hall, the New Brunswick Free Public Library, and the New Brunswick Main Post Office are located in the city's Civic Square government district, as are numerous other city, county, state, and federal offices.

Local government

[edit]

The City of New Brunswick is governed within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under the Mayor-Council system of municipal government. The city is one of 71 municipalities (of the 564) statewide governed under this form.[227] The governing body is comprised of the Mayor and the five-member City Council, all of whom are elected at-large on a partisan basis to four-year terms of office in even-numbered years as part of the November general election. The City Council's five members are elected on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats coming up for election every other year and the mayor up for election at the same time that two council seats are up for vote. As the legislative body of New Brunswick's municipal government, the City Council is responsible for approving the annual budget, ordinances and resolutions, contracts, and appointments to boards and commissions. The Council President is elected to a two-year term by the members of the Council at a reorganization meeting held after election and presides over all meetings.[8][228][229]

As of 2024[update], Democrat James Cahill is the 62nd mayor of New Brunswick; he was sworn in as mayor on January 1, 1991, and is serving a term that expires on December 31, 2026.[3] Members of the City Council are Council President Rebecca H. Escobar (D, 2026), Council Vice President John A. Anderson (D, 2024), Manuel J. Castañeda (D, 2024), Matthew Ferguson (D, 2026; appointed to serve an unexpired term), Glenn J. Fleming (D, 2024), Petra N. Gaskins (D, 2026) and Suzanne M. Sicora Ludwig (D, 2024).[230][231][232][233]

In January 2024, the city council appointed Matthew Ferguson to fill the seat expiring in December 2026 that had been held by Kevin Egan until he resigned earlier that month to take a seat in the New Jersey General Assembly. Ferguson will serve on an interim basis until the November general election, when voters will choose a candidate to serve the balance of the term of office.[234]

In January 2023, the City Council expanded from five to seven members. Gaskins was sworn in as the first black woman and youngest in history, and Castañeda was elected as the first Latino man.[235]

Emergency services

[edit]Police department

[edit]The New Brunswick Police Department has received attention for various incidents over the years. In 1991, the fatal shooting of Shaun Potts, an unarmed black resident, by Sergeant Zane Grey led to multiple local protests.[236] In 1996, Officer James Consalvo fatally shot Carolyn "Sissy" Adams, an unarmed prostitute who had bit him.[237] The Adams case sparked calls for reform in the New Brunswick Police Department, and ultimately was settled with the family.[238] Two officers, Sgt. Marco Chinchilla and Det. James Marshall, were convicted of running a bordello in 2001. Chinchilla was sentenced to three years and Marshall was sentenced to four.[239] In 2011, Officer Brad Berdel fatally shot Barry Deloatch, a black man who had run from police (although police claim he struck officers with a stick);[240] this sparked daily protests from residents.[241]

Following the Deloatch shooting, sergeant Richard Rowe was formally charged with mishandling 81 Internal Affairs investigations; Mayor Cahill explained that this would help "rebuild the public's trust and confidence in local law enforcement."[242]

Fire department

[edit]The current professional city fire department was established in 1914, but the earliest volunteer fire company in the city dates back to 1764. The department operates out of three stations, with a total of approximately 90 officers and firefighters.[243]

In 2014, the city received criticism and public attention after fire director Robert Rawls, whose driving record included dozens of accidents and license suspensions, had struck three children in a crosswalk while driving a city-owned vehicle.[244]

Federal, state and county representation

[edit]New Brunswick is located in the 6th Congressional District[245] and is part of New Jersey's 17th state legislative district.[246][247][248]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 6th congressional district is represented by Frank Pallone (D, Long Branch).[249][250] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[251] and George Helmy (Mountain Lakes, term ends 2024).[252][253]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 17th legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Bob Smith (D, Piscataway) and in the General Assembly by Joseph Danielsen (D, Franklin Township) and Kevin Egan (D, New Brunswick).[254]

Middlesex County is governed by a Board of County Commissioners, whose seven members are elected at-large on a partisan basis to serve three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats coming up for election each year as part of the November general election. At an annual reorganization meeting held in January, the board selects from among its members a commissioner director and deputy director.[255] As of 2024[update], Middlesex County's Commissioners (with party affiliation, term-end year, and residence listed in parentheses) are:

Director Ronald G. Rios (D, Carteret, 2024),[256] Deputy Director Shanti Narra (D, North Brunswick, 2024),[257] Claribel A. "Clary" Azcona-Barber (D, New Brunswick, 2025),[258] Charles Kenny (D, Woodbridge Township, 2025),[259] Leslie Koppel (D, Monroe Township, 2026),[260] Chanelle Scott McCullum (D, Piscataway, 2024)[261] and Charles E. Tomaro (D, Edison, 2026).[262][263]

Constitutional officers are: Clerk Nancy Pinkin (D, 2025, East Brunswick),[264][265] Sheriff Mildred S. Scott (D, 2025, Piscataway)[266][267] and Surrogate Claribel Cortes (D, 2026; North Brunswick).[268][269][270]

Politics

[edit]As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 22,742 registered voters in New Brunswick, of which 8,732 (38.4%) were registered as Democrats, 882 (3.9%) were registered as Republicans and 13,103 (57.6%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 25 voters registered to other parties.[271]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020[272] | 17.1% 1,608 | 81.4% 7,639 | 1.5% 139 |

| 2016[273] | 14.1% 1,516 | 81.9% 8,776 | 4.0% 426 |

| 2012[274] | 14.3% 1,576 | 83.4% 9,176 | 2.2% 247 |

| 2008[275] | 14.8% 1,899 | 83.3% 10,717 | 1.1% 140 |

| 2004[148] | 19.7% 2,018 | 78.2% 8,023 | 1.4% 143 |

In the 2016 presidential election, Democrat Hillary Clinton received 81.9% of the vote (8,779 cast), ahead of Republican Donald Trump with 14.1% (1,516 votes), and other candidates with 4.0% (426 votes), among the 10,721 ballots cast.[276] In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 83.4% of the vote (9,176 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 14.3% (1,576 votes), and other candidates with 2.2% (247 votes), among the 11,106 ballots cast by the township's 23,536 registered voters (107 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 47.2%.[277][278] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 83.3% of the vote (10,717 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain with 14.8% (1,899 votes) and other candidates with 1.1% (140 votes), among the 12,873 ballots cast by the township's 23,533 registered voters, for a turnout of 54.7%.[275]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[279] | 19.2% 721 | 79.2% 2,972 | 1.6% 60 |

| 2017[280] | 13.6% 590 | 83.1% 3,616 | 3.4% 148 |

| 2013[281] | 31.2% 1,220 | 66.5% 2,604 | 2.3% 92 |

| 2009[282] | 20.9% 1,314 | 68.2% 4,281 | 8.2% 515 |

| 2005[283] | 17.2% 880 | 76.9% 3,943 | 4.2% 214 |

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 66.5% of the vote (2,604 cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 31.2% (1,220 votes), and other candidates with 2.3% (92 votes), among the 3,991 ballots cast by the township's 23,780 registered voters (75 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 16.8%.[284][285] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 68.2% of the vote (4,281 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 20.9% (1,314 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 6.2% (387 votes) and other candidates with 2.0% (128 votes), among the 6,273 ballots cast by the township's 22,534 registered voters, yielding a 27.8% turnout.[282]

Education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]The New Brunswick Public Schools serve students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grade.[286] The district is one of 31 former Abbott districts statewide that were established pursuant to the decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court in Abbott v. Burke[287] which are now referred to as "SDA Districts" based on the requirement for the state to cover all costs for school building and renovation projects in these districts under the supervision of the New Jersey Schools Development Authority.[288][289] The district's nine-member Board of Education is elected at large, with three members up for election on a staggered basis each April to serve three-year terms of office; until 2012, the members of the Board of Education were appointed by the city's mayor.[290]

As of the 2022–23 school year, the district, comprised of 12 schools, had an enrollment of 9,690 students and 777.4 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 12.5:1.[291] Schools in the district (with 2022–23 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[292]) are Lincoln Elementary School[293] (578; K-4), Livingston Elementary School[294] (342; K-5), Lord Stirling Elementary School[295] (490; PreK-5), McKinley Community Elementary School[296] (640; PreK-8), A. Chester Redshaw Elementary School[297] (784; PreK-5), Paul Robeson Community School For The Arts[298] (665; K-8), Roosevelt Elementary School[299] (609; K-5), Blanquita B. Valenti Community School[300] (opened 2023-24: 569 in grades 4–8), Woodrow Wilson Elementary School[301] (373; PreK-8), New Brunswick Middle School[302] (1,259; 6–8) and New Brunswick High School[303] (2,477; 9–12).[304][305][306][307]

The community is also served by the Greater Brunswick Charter School, a K–8 charter school serving students from New Brunswick, Edison, Highland Park and Milltown.[308] As of the 2021–22 school year, the school had an enrollment of 399 students and 32.5 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 12.3:1.[309]

Eighth grade students from all of Middlesex County are eligible to apply to attend the high school programs offered by the Middlesex County Vocational and Technical Schools, a county-wide vocational school district that offers full-time career and technical education at Middlesex County Academy in Edison, the Academy for Allied Health and Biomedical Sciences in Woodbridge Township and at its East Brunswick, Perth Amboy and Piscataway technical high schools, with no tuition charged to students for attendance.[310][311]

Higher education

[edit]- Rutgers University has three campuses in the city: College Avenue Campus (seat of the university), Douglass Campus, and Cook Campus, which extend into surrounding townships. Rutgers has also added several buildings downtown in the last two decades, both academic and residential.[312]

- New Brunswick is the site to the New Brunswick Theological Seminary, a seminary of the Reformed Church in America, that was founded in New York in 1784, then moved to New Brunswick in 1810.[51]

- Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, part of Rutgers University, is located in New Brunswick and Piscataway.[313]

- Middlesex County College has some facilities downtown, though its main campus is in Edison.[314]

Historic district

[edit]The Livingston Avenue Historic District is a historic district located along Livingston Avenue between Hale and Morris Streets. The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places on February 16, 1996, for its significance in architecture, social history, and urban history from 1870 to 1929.[315][316]

- John B. Drury House, Victorian style

- Roosevelt Intermediate School, Neo-Classical Revival style

- Ukrainian Catholic Church, Richardsonian Romanesque style

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Roads and highways

[edit]

As of May 2010[update], the city had 73.24 miles (117.87 km) of roadways, of which 56.13 miles (90.33 km) were maintained by the municipality, 8.57 miles (13.79 km) by Middlesex County, 7.85 miles (12.63 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 0.69 miles (1.11 km) by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority.[317]

The city is crisscrossed a wide range of roads and highways.[318] In the city is the intersection of U.S. Route 1[319] and Route 18,[320] and is bisected by Route 27.[321] New Brunswick hosts less than a mile of the New Jersey Turnpike (Interstate 95).[322] A few turnpike ramps are in the city that lead to Exit 9 which is just outside the city limits in East Brunswick.[323]

Other major roads that are nearby include the Garden State Parkway in Woodbridge Township and Interstate 287 in neighboring Edison, Piscataway and Franklin townships.

The New Brunswick Parking Authority manages 14 ground-level and multi-story parking facilities across the city.[324][325] CitiPark manages a downtown parking facility at 2 Albany Street.[326][327]

Public transportation

[edit]

New Brunswick is served by NJ Transit and Amtrak trains on the Northeast Corridor Line.[328] NJ Transit provides frequent service north to Pennsylvania Station, in Midtown Manhattan, and south to Trenton, while Amtrak's Keystone Service and Northeast Regional trains service the New Brunswick station.[329] The Jersey Avenue station is also served by Northeast Corridor trains.[330] For other Amtrak connections, riders can take NJ Transit to Penn Station (New York or Newark), Trenton, or Metropark.

Local bus service is provided by NJ Transit's 810, 811, 814, 815, and 818 routes.[331][332]

Also available is the extensive Rutgers Campus bus network.[333] Middlesex County Area Transit (MCAT) shuttles provide service on routes operating across the county,[334] including the M1 route, which operates between Jamesburg and the New Brunswick train station.[335] DASH/CAT buses, operated by Somerset County on the 851 and 852 routes connect New Brunswick and Bound Brook.[336][337]

Suburban Trails offers service to and from New York City on Route 100 between Princeton and the Port Authority Bus Terminal; on Route 500 between New Brunswick and along 42nd Street to the United Nations; and Route 600 between East Windsor and Wall Street in Downtown Manhattan.[338] Studies are being conducted to create the New Brunswick Bus Rapid Transit system.

Intercity bus service from New Brunswick to Columbia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., is offered by OurBus Prime.[339]

New Brunswick was at the eastern terminus of the Delaware and Raritan Canal, of which there are remnants surviving or rebuilt along the river.[340] Until 1936, the city was served by the interurban Newark–Trenton Fast Line, which covered a 72-mile (116 km) route that stopped in New Brunswick as it ran between Jersey City and Trenton.[341]

The Raritan River Railroad ran to New Brunswick, but is now defunct along this part of the line. The track and freight station still remain. Proposals have been made to use the line as a light rail route that would provide an option for commuters now driving in cars on Route 18.[342]

Old Bridge Airport in Old Bridge supply short-distance flights to surrounding areas and is the closest air transportation services. The next nearest commercial airports are Princeton Airport located 14 miles (23 km) southwest (about 23 minutes drive); and Newark Liberty International Airport, which serves as a major hub for United Airlines and located 22 miles (35 km) north (about 31 minutes drive) from New Brunswick.[343][344]

Healthcare

[edit]

Saint Peter's University Hospital, Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, the Cancer Institute of New Jersey, and The Bristol-Myers Squibb Children's Hospital are all located in the city of New Brunswick.[175] The city is aptly named the 'Healthcare city' for its wide array of public and private healthcare services.

Popular culture

[edit]- On April 18, 1872, at New Brunswick, William Cameron Coup developed the system of transporting circus equipment, staff and animals from city to city using railroad cars. This system would be adopted by other railroad circuses and used through the golden age of railroad circuses until the 2017 closure of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.[345]

- The play and movie 1776 discusses the Continental Army under General George Washington being stationed at New Brunswick in June 1776 and being inspected by John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Chase of Maryland as members of the War Committee.

- The 1980s sitcom, Charles in Charge, was set in New Brunswick.[346]

- The 2004 movie Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle revolves around Harold and Kumar's attempt to get to a White Castle restaurant and includes a stop in a fictionalized New Brunswick.[347]

- The 2007 Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao is primarily set in New Brunswick.[348]

- The 2013 novel Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie features a taxi driver bragging about having a daughter on the dean's list at Rutgers.[349]

- Bands from New Brunswick include The Gaslight Anthem,[350] Screaming Females, Streetlight Manifesto,[351] Thursday and Bouncing Souls.[352]

- The independent record label Don Giovanni Records was established in 2003 to document the music scene in New Brunswick.[353]

- The store run scene in the movie Little Man was filmed in New Brunswick.

Points of interest

[edit]

- Albany Street Bridge, a seven-span stone arch bridge dating to 1892 that was used as part of the transcontinental Lincoln Highway. It stretches 595 feet (181 m) across the Raritan River to Highland Park.[354][355]

- Bishop House, located at 115 College Avenue, is an Italianate architecture mansion built for James Bishop and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.[356]

- The historic Old Queens Campus and Voorhees Mall at Rutgers University – Old Queens, built in 1809, is the oldest building at Rutgers University. The building's cornerstone was laid in 1809.[47]

- Buccleuch Mansion in Buccleuch Park. Built in 1739 by Anthony White as part of a working farm and home overlooking Raritan Landing, the house and its adjoining 79 acres (32 ha) of land were deeded to the City of New Brunswick to be used as a park in 1911.[357][358]

- Christ Church Episcopal Churchyard had its earliest burial in 1754 and includes the grave sites of slaves.[359]

- The Henry Guest House, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, is a Georgian stone farmhouse built in 1760 by Henry Guest at Livingston Avenue and Morris Street that was moved in 1924 next to the New Brunswick Free Public Library after plans were made to demolish the building at its original site.[360]

- William H. Johnson House is an example of Italianate architecture built c. 1870, when New Brunswick experienced a post-Civil War economic boom. Architectural components including the tall narrow windows with arched tops, double bays, cornice brackets and low pitched roofs exemplify the Italianate style. The house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in July 2006.[361][362]

- St. Peter the Apostle Church, built in 1856 and designed by Patrick Keeley, is located at 94 Somerset Street.[363]

- Delaware and Raritan Canal – Completed in 1834, the canal reached its peak in the 1860s and 1870s, when its primary use was to transport coal from Pennsylvania to New York City. Accessing the canal at Bordentown on the Delaware River, the main route covered 44 miles (71 km) to New Brunswick on the Raritan River.[364]

- Birthplace of poet Joyce Kilmer – Located on Joyce Kilmer Avenue, the building is where the poet and essayist was born on December 6, 1886. Acquired by a local American Legion post, the building and its second-floor memorial to Kilmer was sold to the state in the 1960s, which then transferred it to the ownership of the City of New Brunswick.[365]

- Site of Johnson & Johnson world headquarters

- The Willow Grove Cemetery – located behind the Henry Guest House and the New Brunswick Free Public Library, the site of the cemetery was acquired in the late 1840s, the cemetery association was incorporated in 1850 and a state charter was granted the following year.[366]

- Mary Ellis grave (1750–1828) stands out due to its location in the AMC Theatres parking lot on U.S. Route 1 downriver from downtown New Brunswick.[367]

- Lawrence Brook, a tributary of the Raritan River has a watershed covering 48 square miles (120 km2) that includes New Brunswick, as well as East Brunswick, Milltown, North Brunswick and South Brunswick.[368]

- Elmer B. Boyd Park, a park running along the Raritan River, covering 20 acres (8.1 ha) adjacent to Route 18, the park went through an $11 million renovation project and reopened to the public in 1999.[369][370]

Places of worship

[edit]- Abundant Life Family Worship Church – founded in 1991.[371]

- Anshe Emeth Memorial Temple (Reform Judaism) – established in 1859.[372]

- Ascension Lutheran Church – founded in 1908 as The New Brunswick First Magyar Augsburg Evangelical Church.[373]

- Christ Church, Episcopal – granted a royal charter in 1761.[374]

- Ebenezer Baptist Church

- First Baptist Church of New Brunswick, American Baptist

- First Presbyterian, Presbyterian (PCUSA)

- First Reformed Reformed (RCA)

- Kirkpatrick Chapel at Rutgers University (nondenominational)

- Magyar Reformed, Calvinist

- Mount Zion AME (African Methodist Episcopal)

- Mt. Zion Ministries Family Worship Church

- Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church

- New Brunswick Islamic Center

- Point Community Church

- Saint Joseph, Byzantine Catholic

- Saint Ladislaus, Roman Catholic

- Saint Mary of Mount Virgin Church, Remsen Avenue and Sandford Street, Roman Catholic

- Sacred Heart Church, Throop Avenue, Roman Catholic

- Saint Peter the Apostle Church, Somerset Street, Roman Catholic

- Second Reformed Church, Reformed (RCA)

- Sharon Baptist Church

- United Methodist Church at New Brunswick

- Voorhees Chapel at Rutgers University (nondenominational)

Notable people

[edit]

People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with the City of New Brunswick include:

- David Abeel (1804–1846), Dutch Reformed Church missionary[375]

- Garnett Adrain (1815–1878), member of the United States House of Representatives[376]

- Charlie Atherton (1874–1934), major league baseball player[377]

- Jim Axelrod (born 1963), national correspondent for CBS News who is a reporter for the CBS Evening News[378]

- Catherine Hayes Bailey (1921–2014), plant geneticist who specialized in fruit breeding[379]

- Joe Barzda (1915–1993), race car driver[380][381]

- John Bayard (1738–1807), merchant, soldier and statesman who was a delegate for Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress in 1785 and 1786, and later mayor of New Brunswick[382]

- John Bradbury Bennet (1865–1940), United States Army officer and brigadier general active during World War I[383]

- James Berardinelli (born 1967), film critic[384][385]

- James Bishop (1816–1895), represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1855 to 1857[386]

- Charles S. Boggs (1811–1877), Rear Admiral who served in the United States Navy during the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War[387]

- PJ Bond, singer-songwriter[388]

- Jake Bornheimer (1927–1986), professional basketball player for the Philadelphia Warriors[389]

- James Bornheimer (1933–1993), politician who served in the New Jersey General Assembly from 1972 to 1982 and in the New Jersey Senate from 1982 to 1984[390]

- Brett Brackett (born 1987), football tight end[391]

- Derrick Drop Braxton (born 1981), record producer and composer[392]

- Sherry Britton (1918–2008), burlesque performer and actress[393]

- Gary Brokaw (born 1954), former professional basketball player who played most of his NBA career for the Milwaukee Bucks[394]

- Dana Brown (born 1967), general manager of the Houston Astros of Major League Baseball[395]

- Jalen Brunson (born 1996), basketball player[396]

- William Burdett-Coutts (1851–1921), British Conservative politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1885 to 1921[397]

- Darhyl Camper (born 1990), singer-songwriter and record producer[398]

- Arthur S. Carpender (1884–1960), United States Navy admiral who commanded the Allied Naval Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area during World War II[399]

- Jonathan Casillas (born 1987), linebacker for the NFL's New Orleans Saints and University of Wisconsin[400]

- Joseph Compton Castner (1869–1946), Army general[401]

- Chris Dailey (born 1959), women's basketball coach, who has been the associate head coach for the Connecticut Huskies women's basketball team since 1988[402]

- Andre Dixon (born 1986), former professional football running back[403]

- Wheeler Winston Dixon (born 1950), filmmaker, critic and author[404][405]

- Michael Douglas (born 1944), actor[406]

- Kevin Egan (born 1964), politician who has represented the 17th legislative district in the New Jersey General Assembly since 2024[407]

- Hallie Eisenberg (born 1992), actress[408]

- Linda Emond (born 1959), actress[409]

- Jerome Epstein (born 1937), politician who served in the New Jersey Senate from 1972 to 1974 and later went to federal prison for pirating millions of dollars worth of fuel oil[410]

- Anthony Walton White Evans (1817–1886), engineer[411]

- Robert Farmar (1717–1778), British Army officer who fought in the Seven Years' War and served as interim governor of British West Florida[412]

- Mervin Field (1921–2015), pollster of public opinion[413]

- Louis Michael Figueroa (born 1966), arguably the most prolific transcontinental journeyman[414]

- Charles Fiske (1868–1942), bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Central New York from 1924 to 1936[415]

- Haley Fiske (1852–1929), lawyer who served as President of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company[416]

- Kevin Friedland (born 1981), soccer defender who played for Minnesota United FC.[417]

- Margaret Kemble Gage (1734–1824), wife of General Thomas Gage, who led the British Army in Massachusetts early in the American Revolutionary War and who may have informed the revolutionaries of her husband's strategy[418]

- Morris Goodkind (c. 1888–1968), chief bridge engineer for the New Jersey State Highway Department from 1925 to 1955 (now the New Jersey Department of Transportation), responsible for the design of the Pulaski Skyway and 4,000 other bridges[419]

- Vera Mae Green (1928–1982), anthropologist, educator and scholar, who made major contributions in the fields of Caribbean studies, interethnic studies, black family studies and the study of poverty and the poor[420]

- Alan Guth (born 1947), theoretical physicist and cosmologist best known for his theory of cosmological inflation[421]

- Augustus A. Hardenbergh (1830–1889), represented New Jersey's 7th congressional district from 1875 to 1879, and again from 1881 to 1883[422]

- Mel Harris (born 1956), actress[423]

- Mark Helias (born 1950), jazz bassist / composer[424]

- Susan Hendricks (born 1973), anchor for HLN and substitute anchor for CNN[425]

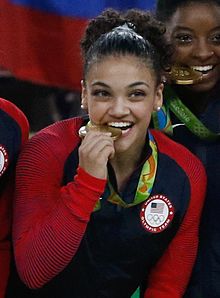

- Laurie Hernandez (born 2000), artistic gymnast representing Team USA at the 2016 Summer Olympics[426]

- Sabah Homasi (born 1988), mixed martial artist who competes in the welterweight division[427]

- Christine Moore Howell (1899–1972), hair care product businesswoman who founded Christine Cosmetics[428]

- Adam Hyler (1735–1782), privateer during the American Revolutionary War[429]

- Bill Hynes (born 1972), professional auto racing driver and entrepreneur[430]

- Jaheim (born 1978, full name Jaheim Hoagland), R&B singer[431]

- Dwayne Jarrett (born 1986), wide receiver for the University of Southern California football team 2004 to 2006, current WR drafted by the Carolina Panthers[432]

- James P. Johnson (1891–1955), pianist and composer who was one of the original stride piano masters[433]

- William H. Johnson (1829–1904), painter and wallpaper hanger, businessman and local crafts person, whose home (c. 1870) was placed on the State of New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places in 2006[434]

- Robert Wood Johnson I (1845–1910), businessman who was one of the founders of Johnson & Johnson[435]

- Robert Wood Johnson II (1893–1968), businessman who led Johnson & Johnson and served as mayor of Highland Park, New Jersey[436]

- Woody Johnson (born 1947), businessman, philanthropist, and diplomat who is currently serving as United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom[437]

- Frederick Barnett Kilmer (1851–1934), pharmacist, author, public health activist and the director of Scientific Laboratories for Johnson & Johnson from 1889 to 1934[438]

- Joyce Kilmer (1886–1918), poet[439]

- Littleton Kirkpatrick (1797–1859), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1853 to 1855, and was mayor of New Brunswick in 1841 and 1842[440]

- Ted Kubiak (born 1942), MLB player for the Kansas City/Oakland Athletics, Milwaukee Brewers, St. Louis Cardinals, Texas Rangers, and the San Diego Padres[441]

- Jerry Levine (born 1957), actor and director of television and theater, best known for appearing on Will & Grace and in the films Teen Wolf and Casual Sex?[442]

- Roy Mack (1889–1962), director of film shorts, mostly comedies, with 205 titles to his credit[443]

- Floyd Mayweather Jr. (born 1977), multi-division winning boxer, currently with an undefeated record of 50–0; he grew up in the 1980s in the Hiram Square neighborhood[444]

- Jim Norton (born 1968), comedian[445]

- Anna Oliver (1840–1892), American preacher[446]

- Robert Pastorelli (1954–2004), actor known primarily for playing the role of the house painter on Murphy Brown[447]

- Judith Persichilli (born 1949), nurse and health care executive who has served as the Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Health[448]

- Hasan Piker (born 1991), Twitch streamer and political commentator[449][450]

- Stephen Porges (born 1945), Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill[451]

- Franke Previte (born 1946), composer[452]

- Paul Reale (1943–2020), composer and pianist[453]

- Mary Lea Johnson Richards (1926–1990), heiress, entrepreneur and Broadway producer, who was the first baby to appear on a Johnson's baby powder label[454]

- Miles Ross (1827–1903), Mayor of New Brunswick, U.S. Representative and businessman[455]

- Mohamed Sanu (born 1989), American football wide receiver who has played in the NFL for the New England Patriots and San Francisco 49ers[456]

- Gabe Saporta (born 1979), musician and frontman of bands Midtown and Cobra Starship[457]

- Robert J. Sexton, director, producer, and former musician[458]

- Jeff Shaara (born 1952), historical novelist[459]

- Gerald Shargel (1944–2022), defense attorney known for his work defending mobsters and celebrities.[460]

- Dustin Sheppard (born 1980), retired professional soccer player who played in MLS for the MetroStars[461]

- Brian D. Sicknick (1978–2021), officer of the United States Capitol Police who died following the January 6 United States Capitol attack.[462]

- George Sebastian Silzer (1870–1940), served as the 38th Governor of New Jersey. Served on the New Brunswick board of aldermen from 1892 to 1896[463]

- James H. Simpson (1813–1883), U.S. Army surveyor of western frontier areas[464]

- Robert Sklar (1936–2011), historian and author specializing in the history of film.[465]

- Arthur Space (1908–1983), actor of theatre, film, and television[466]

- Larry Stark (born 1932), theater reviewer and creator of Theater Mirror[467]

- Matt Taibbi (born 1970), author and journalist[468]

- Norman Tanzman (1918–2004), politician who served in the New Jersey General Assembly from 1962 to 1968 and in the New Jersey Senate from 1968 to 1974[469]

- Ron "Bumblefoot" Thal (born 1969), guitarist, musician, composer[470]

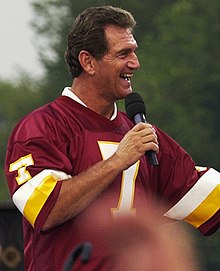

- Joe Theismann (born 1949), former professional quarterback who played in the NFL for the Washington Redskins and former commentator on ESPN's Monday Night Football[471]

- John Tukey (1915–2000), mathematician[472]

- William Henry Vanderbilt (1821–1885), businessman[473]

- John Van Dyke (1807–1878), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1847 to 1851, and served as Mayor of New Brunswick from 1846 to 1847[474]

- Tony Vega (1961–2013), Thoroughbred horse jockey and community activist[475]

- George Veronis (1926–2019), geophysicist[476]

- Paul Wesley (born 1982), actor, known for his role as "Stefan Salvatore" on The CW show The Vampire Diaries[477]

- Rev. Samuel Merrill Woodbridge (1819–1905), minister, author, professor at Rutgers College and New Brunswick Theological Seminary[478]

- Eric Young (born 1967), former Major League Baseball player who is currently the first base coach for the Atlanta Braves[479]

- Eric Young Jr. (born 1985), Major League Baseball player[480]

Sister cities

[edit]New Brunswick's sister cities are:[481][482]

Debrecen, Hungary

Debrecen, Hungary Fukui, Fukui Prefecture, Japan

Fukui, Fukui Prefecture, Japan County Limerick, Ireland

County Limerick, Ireland Tsuruoka, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan

Tsuruoka, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places Archived March 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990 Archived August 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Mayor's Office, City of New Brunswick. Accessed April 14, 2024.

- ^ 2023 New Jersey Mayors Directory Archived March 11, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, updated February 8, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b City Directory, City of New Brunswick. Accessed April 14, 2024.

- ^ Administration Staff, City of New Brunswick. Accessed April 14, 2024.

- ^ Leslie Zeledón Appointed as New City Clerk Archived December 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, City of New Brunswick. Accessed December 11, 2019. "New Brunswick City Council appointed Leslie R. Zeledón as the new City Clerk at its 2019 Reorganization Meeting at City Hall. Zeledón has served as Deputy Clerk for the City of New Brunswick since September 2011. She replaces longtime City Clerk Daniel A. Torrisi, who was appointed by Mayor Cahill to serve as City Administrator."

- ^ a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 81.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "City of New Brunswick". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e QuickFacts New Brunswick city, New Jersey Archived November 10, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities Archived February 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021 Archived March 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 20,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2023 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 30, 2024. Note that townships (including Edison, Lakewood and Woodbridge, all of which have larger populations) are excluded from these rankings.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for New Brunswick, NJ Archived March 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, United States Postal Service. Accessed April 18, 2012.

- ^ Zip Codes Archived June 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed August 18, 2013.

- ^ Area Code Lookup – NPA NXX for New Brunswick, NJ Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Area-Codes.com. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- ^ U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey Archived November 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.