Life of Jesus

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

| Portals: |

The life of Jesus is primarily outlined in the four canonical gospels, which includes his genealogy and nativity, public ministry, passion, prophecy, resurrection and ascension.[2][3] Other parts of the New Testament – such as the Pauline epistles which were likely written within 20 to 30 years of each other,[4] and which include references to key episodes in the life of Jesus, such as the Last Supper,[2][3][5] and the Acts of the Apostles (1:1–11), which includes more references to the Ascension episode than the canonical gospels[6][7] also expound upon the life of Jesus. In addition to these biblical texts, there are extra-biblical texts that make reference to certain events in the life of Jesus, such as Josephus on Jesus and Tacitus on Christ.

In the gospels, the ministry of Jesus starts with his Baptism by John the Baptist. Jesus came to the Jordan River where he was baptized by John the Baptist, after which he fasted for forty days and nights in the Judaean Desert. This early period also includes the first miracle of Jesus in the Marriage at Cana.

The principal locations for the ministry of Jesus were Galilee and Judea, with some activities also taking place in nearby areas such as Perea and Samaria. Jesus' activities in Galilee include a number of miracles and teachings.

Genealogy and Nativity

[edit]

The genealogy and Nativity of Jesus are described in two of the four canonical gospels: the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke.[8] While Luke traces the genealogy upwards towards Adam and God, Matthew traces it downwards towards Jesus.[9] Both gospels state that Jesus was begotten not by Joseph, but conceived miraculously in the womb of Mary, mother of Jesus by the Holy Spirit.[10] Both accounts trace Joseph back to King David and from there to Abraham. These lists are identical between Abraham and David (except for one), but they differ almost completely between David and Joseph.[11][12] Matthew gives Jacob as Joseph's father and Luke says Joseph was the son of Heli. Attempts at explaining the differences between the genealogies have varied in nature.[13][14][15] Much of modern scholarship interprets them as literary inventions.[16]

The Luke and Matthew accounts of the birth of Jesus have a number of points in common; both have Jesus being born in Bethlehem, in Judea, to a virgin mother. In the Luke account Joseph and Mary travel from their home in Nazareth for the census to Bethlehem, where Jesus is born and laid in a manger.[17] Angels proclaim him a savior for all people, and shepherds come to adore him; the family then returns to Nazareth. In Matthew, The Magi follow a star to Bethlehem, where the family are living, to bring gifts to Jesus, born the King of the Jews. King Herod massacres all males under two years old in Bethlehem in order to kill Jesus, but Jesus's family flees to Egypt and later settles in Nazareth. Over the centuries, biblical scholars have attempted to reconcile these contradictions,[18] while modern scholarship mostly views them as legendary.[19][20][21][22][23] Generally, they consider the issue of historicity as secondary, given that gospels were primarily written as theological documents rather than chronological timelines.[24][25][26][27]

Ministry

[edit]

The five major milestones in the New Testament narrative of the life of Jesus are his Baptism, Transfiguration, Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension.[28][29][30]

In the gospels, the ministry of Jesus starts with his Baptism by John the Baptist, when he is about thirty years old. Jesus then begins preaching in Galilee and gathers disciples.[31][32] After the proclamation of Jesus as Christ, three of the disciples witness his Transfiguration.[33][34] After the death of John the Baptist and the Transfiguration, Jesus starts his final journey to Jerusalem, having predicted his own death there.[35] Jesus makes a triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and there friction with the Pharisees increases and one of his disciples agrees to betray him for thirty pieces of silver.[36][37][38]

In the gospels, the ministry of Jesus begins with his baptism in the countryside of Roman Judea and Transjordan, near the river Jordan, and ends in Jerusalem, following the Last Supper with his disciples.[32] The Gospel of Luke (3:23) states that Jesus was "about 30 years of age" at the start of his ministry.[39][40] A chronology of Jesus typically has the date of the start of his ministry estimated at 27–29 and the end in the range 30–36.[39][40][41][42]

Jesus's early Galilean ministry begins when after his Baptism he goes back to Galilee from his time in the Judean desert.[43] In this early period he preaches around Galilee and recruits his first disciples who begin to travel with him and eventually form the core of the early Church[31][32] as it is believed that the Apostles dispersed from Jerusalem to found the Apostolic Sees. The Major Galilean ministry which begins in Matthew 8 includes the commissioning of the Twelve Apostles, and covers most of the ministry of Jesus in Galilee.[44][45] The Final Galilean ministry begins after the death of John the Baptist as Jesus prepares to go to Jerusalem.[46][47]

In his later Judean ministry Jesus starts his final journey to Jerusalem through Judea.[33][34][48][49] As Jesus travels towards Jerusalem, in the later Perean ministry, about one third the way down from the Sea of Galilee (actually a fresh water lake) along the River Jordan, he returns to the area where he was baptized.[50][51][52] The final ministry in Jerusalem is sometimes called the Passion Week and begins with Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem.[53] The gospels provide more details about the final ministry than the other periods, devoting about one third of their text to the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem.[54] In the gospel accounts, towards the end of the final week in Jerusalem, Jesus has the Last Supper with his disciples, and the next day is betrayed, arrested and tried.[55] The trial ends in his crucifixion and death. Three days after his burial, he is resurrected and appears to his disciples and a multitude of his followers (numbering around 500 in total) over a 40-day period 1 Corinthians 15 NIV[56] after which he ascends to Heaven.[6] [7]

Locations of Ministry

[edit]

In the New Testament accounts, the principle locations for the ministry of Jesus were Galilee and Judea, with activities also taking place in surrounding areas such as Perea and Samaria.[31][32]

The gospel narrative of the ministry of Jesus is traditionally separated into sections that have a geographical nature.

- Galilean ministry: The ministry of Jesus begins when after his baptism, he returns to Galilee, and preaches in the synagogue of Capernaum.[43][57] The first disciples of Jesus encounter him near the Sea of Galilee and his later Galilean ministry includes key episodes such as the Sermon on the Mount (with the Beatitudes) which form the core of his moral teachings.[58][59] Jesus's ministry in the Galilee area draws to an end with the death of John the Baptist.[46][47]

- Journey to Jerusalem: After the death of the Baptist, about half way through the gospels (approximately Matthew 17 and Mark 9) two key events take place that change the nature of the narrative by beginning the gradual revelation of his identity to his disciples: his proclamation as Christ by Peter and his transfiguration.[33][34] After these events, a good portion of the gospel narratives deal with Jesus's final journey to Jerusalem through Perea and Judea.[33][34][48][49] As Jesus travels towards Jerusalem through Perea he returns to the area where he was baptized.[50][51][52]

- Final week in Jerusalem: The final part of Jesus's ministry begins (Matthew 21 and Mark 11) with his triumphal entry into Jerusalem after the raising of Lazarus episode which takes place in Bethany. The gospels provide more details about the final portion than the other periods, devoting about one third of their text to the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem which ends in his crucifixion.[54] The New Testament accounts of the resurrection appearances of Jesus and his ascension are also in Judea.

Baptism and temptation

[edit]

The Baptism of Jesus marks the beginning of his public ministry. This event is recorded in the Canonical Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. In John 1:29–33, rather than a direct narrative, John the Baptist bears witness to the episode.[61][62]

In the New Testament, John the Baptist preached a "baptism with water", not of forgiveness but of penance or repentance for the remission of sins (Luke 3:3), and declared himself a forerunner to one who would baptize 'with the Holy Spirit and with fire' (Luke 3:16). In so doing he was preparing the way for Jesus.[63] Jesus came to the Jordan River where he was baptized by John.[63][64][65] The baptismal scene includes the Heavens opening, a dove-like descent of the Holy Spirit, and a voice from Heaven saying, "This is my beloved Son with whom I am well pleased."[63][66]

Most modern scholars view the fact that Jesus was baptized by John as an historical event to which a high degree of certainty can be assigned.[67][68][69][70] James Dunn states that the historicity of the Baptism and crucifixion of Jesus "command almost universal assent".[71] Along with the crucifixion of Jesus most scholars view it as one of the two historically certain facts about him, and often use it as the starting points for the study of the historical Jesus.[71]

The temptation of Jesus is detailed in the gospels of Matthew,[72] Mark,[73] and Luke.[74] In these narratives, after being baptized, Jesus fasted for forty days and nights in the Judaean Desert. During this time, Satan appeared to Jesus and tempted him. Jesus having refused each temptation, Satan departed and angels came and brought nourishment to Jesus.

Calling the disciples and early Ministry

[edit]

The calling of the first disciples is a key episode in the gospels which begins the active ministry of Jesus, and builds the foundation for the group of people who follow him, and later form the early Church.[75][76] It takes place in Matthew 4:18–22, Mark 1:16–20 and Luke 5:1–11 on the Sea of Galilee. John 1:35–51 reports the first encounter with two of the disciples a little earlier in the presence of John the Baptist. Particularly in the Gospel of Mark the beginning of the ministry of Jesus and the call of the first disciples are inseparable.[77]

In the Gospel of Luke (Luke 5:1–11),[78] the event is part of the first miraculous catch of fish and results in Peter as well as James and John, the sons of Zebedee, joining Jesus vocationally as disciples.[79][80][81] The gathering of the disciples in John 1:35–51 follows the many patterns of discipleship that continue in the New Testament, in that who have received someone else's witness become witnesses to Jesus themselves. Andrew follows Jesus because of the testimony of John the Baptist, Philip brings Nathanael and the pattern continues in John 4:4–26 where the Samaritan Woman at the Well testifies to the town people about Jesus.[82]

This early period also includes the first miracle of Jesus in the Marriage at Cana, in the Gospel of John where Jesus and his disciples are invited to a wedding and when the wine runs out Jesus turns water into wine by performing a miracle.[83][84]

Ministry and miracles in Galilee

[edit]Jesus's activities in Galillee include a number of miracles and teachings. The beginnings of this period include The Centurion's Servant (8:5–13) and Calming the storm (Matthew 8:23–27) both dealing with the theme of faith overcoming fear.[85][86][87] In this period, Jesus also gathers disciples, e.g. calls Matthew.[88] The Commissioning the twelve Apostles relates the initial selection of the twelve Apostles among the disciples of Jesus.[89][90][91]

In the Mission Discourse, Jesus instructs the twelve apostles who are named in Matthew 10:2–3 to carry no belongings as they travel from city to city and preach.[44][45] Separately in Luke 10:1–24 relates the Seventy Disciples, in which Jesus appoints a larger number of disciples and sent them out in pairs with the Missionary's Mandate to go into villages before Jesus arrives there.[92]

After hearing of John the Baptist's death, Jesus withdraws by boat privately to a solitary place near Bethsaida, where he addresses the crowds who had followed him on foot from the towns, and feeds them all by "five loaves and two fish" supplied by a boy.[93] Following this, the gospels present the Walking on water episode in Matthew 14:22–23, Mark 6:45–52 and John 6:16–21 as an important step in developing the relationship between Jesus and his disciples, at this stage of his ministry.[94] The episode emphasizes the importance of faith by stating that when he attempted to walk on water, Peter began to sink when he lost faith and became afraid, and at the end of the episode, the disciples increase their faith in Jesus and in Matthew 14:33 they say: "Of a truth thou art the Son of God".[95]

Major teachings in this period include the Discourse on Defilement in Matthew 15:1–20 and Mark 7:1–23 where in response to a complaint from the Pharisees Jesus states: "What goes into a man's mouth does not make him 'unclean,' but what comes out of his mouth, that is what makes him 'unclean.'".[96]

Following this episode Jesus withdraws into the "parts of Tyre and Sidon" near the Mediterranean Sea where the Canaanite woman's daughter episode takes place in Matthew 15:21–28 and Mark 7:24–30.[97] This episode is an example of how Jesus emphasizes the value of faith, telling the woman: "Woman, you have great faith! Your request is granted."[97] The importance of faith is also emphasized in the Cleansing ten lepers episode in Luke 17:11–19.[98][99]

In the Gospel of Mark, after passing through Sidon Jesus enters the region of the Decapolis, a group of ten cities south east of Galilee, where the Healing the deaf mute miracle is reported in Mark 7:31–37, where after the healing, the disciples say: "He even makes the deaf hear and the mute speak." The episode is the last in a series of narrated miracles which builds up to Peter's proclamation of Jesus as Christ in Mark 8:29.[100]

Proclamation as Christ

[edit]

The Confession of Peter refers to an episode in the New Testament in which in Jesus asks a question to his disciples: "Who do you say that I am?" Apostle Peter proclaims Jesus to be Christ – the expected Messiah. The proclamation is described in the three Synoptic Gospels: Matthew 16:13–20, Mark 8:27–30 and Luke 9:18–20.[101][102]

Peter's Confession begins as a dialogue between Jesus and his disciples in which Jesus begins to ask about the current opinions about himself among "the multitudes", asking: "Who do the multitudes say that I am?"[101] The disciples provide a variety of the common hypotheses at the time. Jesus then asks his disciples about their own opinion: But who do you say that I am? Only Simon Peter answers him: You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.[102][103]

In Matthew 16:17 Jesus blesses Peter for his answer, and later indicates him as the rock of the Church, and states that he will give Peter "the keys of the kingdom of heaven".[104]

In blessing Peter, Jesus not only accepts the titles Christ and Son of God which Peter attributes to him, but declares the proclamation a divine revelation by stating that his Father in Heaven had revealed it to Peter.[105] In this assertion, by endorsing both titles as divine revelation, Jesus unequivocally declares himself to be both Christ and the Son of God.[105] The proclamation of Jesus as Christ is fundamental to Christology and the Confession of Peter, and Jesus's acceptance of the title is a definitive statement for it in the New Testament narrative.[106] While some of this passage may well be authentic, the reference to Jesus as Christ and Son of God is likely to be an addition by Matthew.[107]

Transfiguration

[edit]

The Transfiguration of Jesus is an episode in the New Testament narrative in which Jesus is transfigured and becomes radiant upon a mountain.[108][109] The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew 17:1–9, Mark 9:2–8, Luke 9:28–36) describe it, and 2 Peter 1:16–18 refers to it.[108] In these accounts, Jesus and three of his apostles go to a mountain (the Mount of Transfiguration). On the mountain, Jesus begins to shine with bright rays of light. Then the prophets Moses and Elijah appear next to him and he speaks with them. Jesus is then called "Son" by a voice in the sky, assumed to be God the Father, as in the Baptism of Jesus.[108]

The Transfiguration is one of the miracles of Jesus in the Gospels.[109][110][111] This miracle is unique among others that appear in the Canonical gospels, in that the miracle happens to Jesus himself.[112] Thomas Aquinas considered the Transfiguration "the greatest miracle" in that it complemented baptism and showed the perfection of life in Heaven.[113] The Transfiguration is one of the five major milestones in the gospel narrative of the life of Jesus, the others being Baptism, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension.[28][29] In the New Testament, Transfiguration is a pivotal moment, and the setting on the mountain is presented as the point where human nature meets God: the meeting place for the temporal and the eternal, with Jesus himself as the connecting point, acting as the bridge between heaven and earth.[114]

Final journey to Jerusalem

[edit]

After the death of John the Baptist and the Transfiguration, Jesus starts his final journey to Jerusalem, having predicted his own death there.[35][115][116] The Gospel of John states that during the final journey Jesus returned to the area where he was baptized, and John 10:40–42 states that "many people believed in him beyond the Jordan", saying "all things whatsoever John spake of this man were true".[50][51][52] The area where Jesus was baptised is inferred as the vicinity of the Perea area, given the activities of the Baptist in Bethabara and Ænon in John 1:28 and 3:23.[117][118] Scholars generally assume that the route Jesus followed from Galilee to Jerusalem passed through Perea.[52]

This period of ministry includes the Discourse on the Church in which Jesus anticipates a future community of followers, and explains the role of his apostles in leading it.[119][120] It includes the parables of The Lost Sheep and The Unforgiving Servant in Matthew 18 which also refer to the Kingdom of Heaven. The general theme of the discourse is the anticipation of a future community of followers, and the role of his apostles in leading it.[120][121] Addressing his apostles in 18:18, Jesus states: "what things soever ye shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and what things soever ye shall loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven". The discourse emphasizes the importance of humility and self-sacrifice as the high virtues within the anticipated community. It teaches that in the Kingdom of God, it is childlike humility that matters, not social prominence and prestige.[120][121]

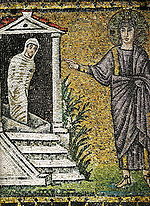

At the end of this period, the Gospel of John includes the Raising of Lazarus episode in John 11:1–46 in which Jesus brings Lazarus of Bethany back to life four days after his burial.[53] In the Gospel of John, the raising of Lazarus is the climax of the "seven signs" which gradually confirm the identity of Jesus as the Son of God and the expected Messiah.[122] It is also a pivotal episode which starts the chain of events that leads to the crowds seeking Jesus on his triumphal entry into Jerusalem – leading to the decision of Caiaphas and the Sanhedrin to plan to kill Jesus.[123]

Final week in Jerusalem

[edit]

The description of the last week of the life of Jesus (often called the Passion week) occupies about one third of the narrative in the canonical gospels.[54] The narrative for that week starts by a description of the final entry into Jerusalem, and ends with his crucifixion.[53][125]

The last week in Jerusalem is the conclusion of the journey which Jesus had started in Galilee through Perea and Judea.[53] Just before the account of the final entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, the Gospel of John includes the Raising of Lazarus episode, which builds the tension between Jesus and the authorities. At the beginning of the week as Jesus enters Jerusalem, he is greeted by the cheering crowds, adding to that tension.[53]

The week begins with the triumphal entry into Jerusalem. During the week of his "final ministry in Jerusalem", Jesus visits the Temple, and has a conflict with the money changers about their use of the Temple for commercial purposes. This is followed by a debate with the priests and the elder in which his authority is questioned. One of his disciples, Judas Iscariot, decides to betray Jesus for thirty pieces of silver.[38]

Towards the end of the week, Jesus has the Last Supper with his disciples, during which he institutes the Eucharist, and prepares them for his departure in the Farewell Discourse. After the supper, Jesus is betrayed with a kiss while he is in Agony in the Garden, and is arrested. After his arrest, Jesus is abandoned by most of his disciples, and Peter denies him three times, as Jesus had predicted during the Last Supper.[126][127] The final week that begins with his entry into Jerusalem, concludes with his crucifixion and burial on that Friday.

Passion

[edit]Betrayal and arrest

[edit]

In Matthew 26:36–46, Mark 14:32–42, Luke 22:39–46 and John 18:1, immediately after the Last Supper, Jesus takes a walk to pray, Matthew and Mark identifying this place of prayer as Garden of Gethsemane.[128][129]

Jesus is accompanied by Peter, John and James the Greater, whom he asks to "remain here and keep watch with me." He moves "a stone's throw away" from them, where he feels overwhelming sadness and says "My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass me by. Nevertheless, let it be as you, not I, would have it."[129] Only the Gospel of Luke mentions the details of the sweat of blood of Jesus and the visitation of the angel who comforts Jesus as he accepts the will of the Father. Returning to the disciples after prayer, he finds them asleep and in Matthew 26:40 he asks Peter: "So, could you men not keep watch with me for an hour?"[129]

While in the Garden, Judas appears, accompanied by a crowd that includes the Jewish priests and elders and people with weapons. Judas gives Jesus a kiss to identify him to the crowd who then arrests Jesus.[129][130] One of Jesus' disciples tries to stop them and uses a sword to cut off the ear of one of the men in the crowd.[129][130] Luke states that Jesus miraculously healed the wound and John and Matthew state that Jesus criticized the violent act, insisting that his disciples should not resist his arrest. In Matthew 26:52 Jesus makes the well known statement: all who live by the sword, shall die by the sword.[129][130]

Justice

[edit]

In the narrative of the four canonical gospels after the betrayal and arrest of Jesus, he is taken to the Sanhedrin, a Jewish judicial body.[131] Jesus is tried by the Sanhedrin, mocked and beaten and is condemned for making claims of being the Son of God.[130][132][133] He is then taken to Pontius Pilate and the Jewish elders ask Pilate to judge and condemn Jesus—accusing him of claiming to be the King of the Jews.[133] After questioning, with few replies provided by Jesus, Pilate publicly declares that he finds Jesus innocent, but the crowd insists on punishment. Pilate then orders Jesus' crucifixion.[130][132][133][134] Although the Gospel accounts vary with respect to various details, they agree on the general character and overall structure of the trials of Jesus.[134]

After the Sanhedrin trial Jesus is taken to Pilate's court in the praetorium. Only in the Gospel of Luke, finding that Jesus, being from Galilee, belonged to Herod Antipas' jurisdiction, Pilate decides to send Jesus to Herod. Herod Antipas (the same man who had previously ordered the death of John the Baptist) had wanted to see Jesus for a long time, because he had been hoping to observe one of the miracles of Jesus.[135] However, Jesus says nothing in response to Herod's questions, or the vehement accusations of the chief priests and the scribes. Herod and his soldiers mock Jesus, put a gorgeous robe on him, as the King of the Jews, and sent him back to Pilate. And Herod and Pilate become friends with each other that day: for before they were at enmity.[136] After questioning Jesus and receiving no replies, Herod sees Jesus as no threat and returns him to Pilate.[137]

After Jesus' return from Herod's court, Pilate publicly declares that he finds Jesus to be innocent of the charges, but the crowd insists on capital punishment. The universal rule of the Roman Empire limited capital punishment strictly to the tribunal of the Roman governor[138] and Pilate decided to publicly wash his hands as not being privy to Jesus' death. Pilate thus presents himself as an advocate pleading Jesus' case rather than as a judge in an official hearing, yet he orders the crucifixion of Jesus.[139][140][141]

Crucifixion and burial

[edit]

Jesus' crucifixion is described in all four canonical gospels, and is attested to by other sources of that age (e.g. Josephus and Tacitus), and is regarded as a historical event.[142][143][144]

After the trials, Jesus made his way to Calvary (the path is traditionally called Via Dolorosa) and the three synoptic gospels indicate that he was assisted by Simon of Cyrene, the Romans compelling him to do so.[145][146] In Luke 23:27–28 Jesus tells the women in multitude of people following him not to cry for him but for themselves and their children.[145] Once at Calvary (Golgotha), Jesus was offered wine mixed with gall to drink — usually offered as a form of painkiller. Matthew's and Mark's gospels state that he refused this.[145][146]

The soldiers then crucified Jesus and cast lots for his clothes. Above Jesus' head on the cross was the inscription King of the Jews, and the soldiers and those passing by mocked him about the title. Jesus was crucified between two convicted thieves, one of whom rebuked Jesus, while the other defended him.[145][147] Each gospel has its own account of Jesus' last words, comprising the seven last sayings on the cross.[148][149][150] In John 19:26–27 Jesus entrusts his mother to the disciple he loved and in Luke 23:34 he states: "Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do", usually interpreted as his forgiveness of the Roman soldiers and the others involved.[148][151][152][153]

In the three synoptic gospels, various supernatural events accompany the crucifixion, including darkness of the sky, an earthquake, and (in Matthew) the resurrection of saints.[146] The tearing of the temple veil, upon the death of Jesus, is referenced in the synoptic.[146] The Roman soldiers did not break Jesus' legs, as they did to the other two men crucified (breaking the legs hastened the crucifixion process), as Jesus was dead already; this further fulfilled prophecy, as noted in John 19:36, "For these things were done, that the scripture should be fulfilled, A bone of him shall not be broken." One of the soldiers pierced the side of Jesus with a lance and blood and water flowed out.[147] In Mark 15:39, impressed by the events, the Roman centurion calls Jesus the Son of God.[145][146][154][155]

Following Jesus' death on Friday, Joseph of Arimathea asked the permission of Pilate to remove the body. The body was removed from the cross, was wrapped in a clean cloth and buried in a new rock-hewn tomb, with the assistance of Nicodemus.[145] In Matthew 27:62–66 the Jews go to Pilate the day after the crucifixion and ask for guards for the tomb and also seal the tomb with a stone as well as the guard, to be sure the body remains there.[145][156][157]

Approximate chronological comparison between the Jesus Passion narratives according to the Gospels of Mark and John. Each section ('1' to '28') represents 3 hours of time.[158]

Resurrection and Ascension

[edit]

The gospels state that the first day of the week after the crucifixion (typically interpreted as a Sunday), the followers of Jesus encounter him risen from the dead, after his tomb was discovered to be empty.[6][7][159][160] The New Testament does not include an account of the "moment of resurrection" and in the Eastern Church icons do not depict that moment, but show the Myrrhbearers, and depict scenes of salvation.[161][162]

The resurrected Jesus then appears to his followers that day and a number of times thereafter, delivers sermons and has supper with some of them, before ascending to Heaven. The gospels of Luke and Mark include brief mentions of the Ascension, but the main references to it are elsewhere in the New Testament.[6][7][160]

The four gospels have variations in their account of the resurrection of Jesus and his appearances, but there are four points at which all gospels converge:[163] the turning of the stone that had closed the tomb, the visit of the women on "the first day of the week;" that the risen Jesus chose first to appear to women (or a woman) and told them (her) to inform the other disciples; the prominence of Mary Magdalene in the accounts.[161][164] Variants have to do with the precise time the women visited the tomb, the number and identity of the women; the purpose of their visit; the appearance of the messenger(s)—angelic or human; their message to the women; and the response of the women.[161]

In Matthew 28:5, Mark 16:5, Luke 24:4 and John 20:12 his resurrection is announced and explained to the followers who arrive there early in the morning by either one or two beings (either men or angels) dressed in bright robes who appear in or near the tomb.[6][7][160] The gospel accounts vary as to who arrived at the tomb first, but they are women and are instructed by the risen Jesus to inform the other disciples. All four accounts include Mary Magdalene and three include Mary, mother of James. The accounts of Mark 16:9, John 20:15 indicate that Jesus appeared to the Magdalene first, and Luke 16:9 states that she was among the Myrrhbearers who informed the disciples about the resurrection.[6][7][160] In Matthew 28:11–15, to explain the empty tomb, the Jewish elders bribe the soldiers who had guarded the tomb to spread the rumor that Jesus' disciples took his body.[7]

Resurrection appearances

[edit]

In John 20:15–17 Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene soon after his resurrection. At first she does not recognize him and thinks that he is the gardener. When he says her name, she recognizes him yet he tells her Noli me Tangere, do not touch me, "for I am not yet ascended to my Father."

Later that day, at evening, Jesus appears to the disciples and shows them the wounds in his hands and his side in John 20:19–21. Thomas the Apostle is not present at that meeting and later expresses doubt about the resurrection of Jesus. As Thomas is expressing his doubts, in the well known Doubting Thomas episode in John 20:24–29 Jesus appears to him and invites him to put his finger into the holes made by the wounds in Jesus' hands and side. Thomas then professes his faith in Jesus. In Matthew 28:16–20, in the Great Commission Jesus appears to his followers on a mountain in Galilee and calls on them to baptize all nations in the name of the "Father, Son, and Holy Spirit".

Luke 24:13–32 describes the Road to Emmaus appearance in which while a disciple named Cleopas was walking towards Emmaus with another disciple, they met Jesus, who later has supper with them. Mark 16:12–13 has a similar account that describes the appearance of Jesus to two disciples while they were walking in the country, at about the same time in the Gospel narrative.[165] In the Miraculous catch of 153 fish Jesus appears to his disciples on the Sea of Galilee, and thereafter Jesus encourages the Apostle Peter to serve his followers.[6][7][160] In 1 Corinthians 15:6–7, the Apostle Paul references an appearance of Jesus to "more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time," along with an appearance to "James" separate from those to the other apostles.

Ascension

[edit]

The Ascension of Jesus (anglicized from the Vulgate Latin Acts 1:9-11 section title: Ascensio Iesu) is the Christian teaching found in the New Testament that the resurrected Jesus was taken up to heaven in his resurrected body, in the presence of eleven of his apostles, occurring 40 days after the resurrection. In the biblical narrative, an angel tells the watching disciples that Jesus' second coming will take place in the same manner as his ascension.[166]

The canonical gospels include two brief descriptions of the Ascension of Jesus in Luke 24:50–53 and Mark 16:19, in which it takes place on Easter Sunday.[167] A more detailed account of Jesus' bodily Ascension into the clouds is given in the Acts of the Apostles (1:9–11) where the narrative starts with the account of Jesus' appearances after his resurrection and describes the event as taking place forty days later.[168][169]

Acts 1:9–12 specifies the location of the Ascension as the "mount called Olivet" near Jerusalem. Acts 1:3 states that Jesus: "showed himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing unto them by the space of forty days, and speaking the things concerning the kingdom of God". After giving a number of instructions to the apostles Acts 1:9 describes the Ascension as follows: "And when he had said these things, as they were looking, he was taken up; and a cloud received him out of their sight." Following this two men clothed in white appear and tell the apostles that Jesus will return in the same manner as he was taken, and the apostles return to Jerusalem.[169]

In Acts 2:30–33, Ephesians 4:8–10 and 1 Timothy 3:16 (where Jesus as taken up in glory) the Ascension is spoken of as an accepted fact, while Hebrews 10:12 describes Jesus as seated in heaven.[170]

See also

[edit]Gospels, chronology and historicity

- Baptism of Jesus

- Christ myth theory

- Chronology of Jesus

- Gospel harmony

- Historical Jesus

- Jesus in Christianity

- Life of Christ in art

- Life of Christ Museum

- Ministry of Jesus

- Timeline of Christianity

- Timeline of the Bible

Associated sites

Notes

[edit]- ^ Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia by Christopher Kleinhenz (Nov 2003) Routledge, ISBN 0415939305 p. 310

- ^ a b Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 pp. 441–442

- ^ a b The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 4 by Erwin Fahlbusch, 2005 ISBN 978-0-8028-2416-5 pp. 52–56

- ^ "When were the Bible books written?". www.gty.org. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0-7814-3868-3 pp. 465–477

- ^ a b c d e f g The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew-Luke, Volume 1 by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0-7814-3868-3 pages 521–530

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament edited by John F. Walvoord, Roy B. Zuck 1983 ISBN 978-0-88207-812-0 page 91

- ^ Luke 3:23–38 Matthew 1:1–17

- ^ Where Christology began: essays on Philippians 2 by Ralph P. Martin, Brian J. Dodd 1998 ISBN 0-664-25619-8 p. 28

- ^ The purpose of the Biblical genealogies by Marshall D. Johnson 1989 ISBN 0-521-35644-X pp. 229–233

- ^ Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke I–IX. Anchor Bible. Garden City: Doubleday, 1981, pp. 499–500.

- ^ I. Howard Marshall, "The Gospel of Luke" (The New International Greek Testament Commentary). Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1978, p. 158.

- ^ The Gospel of Luke by William Barclay 2001 ISBN 0-664-22487-3 pp. 49–50

- ^ Luke: an introduction and commentary by Leon Morris 1988 ISBN 0-8028-0419-5 p. 110

- ^ Cox (2007) pp. 285–286

- ^ Marcus J. Borg, John Dominic Crossan, The First Christmas (HarperCollins, 2009) p. 95.

- ^ "biblical literature." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2011. [1].

- ^ Mark D. Roberts Can We Trust the Gospels?: Investigating the Reliability of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John Good News Publishers, 2007 p. 102

- ^ Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. Bloomsbury. pp. 145–146.

- ^ The Gospel of Matthew by Daniel J. Harrington 1991 ISBN 0-8146-5803-2 p. 47

- ^ Vermes, Géza (2006-11-02). The Nativity: History and Legend. Penguin Books Ltd. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-14-102446-2.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (1993). The historical figure of Jesus. Penguin Books. pp. 85–88. ISBN 9780713990591.

- ^ Jeremy Corley New Perspectives on the Nativity Continuum International Publishing Group, 2009 p. 22.

- ^ Interpreting Gospel Narratives: Scenes, People, and Theology by Timothy Wiarda 2010 ISBN 0-8054-4843-8 pp. 75–78

- ^ Jesus, the Christ: Contemporary Perspectives by Brennan R. Hill 2004 ISBN 1-58595-303-2 p. 89

- ^ The Gospel of Luke by Timothy Johnson 1992 ISBN 0-8146-5805-9 p. 72

- ^ Recovering Jesus: the witness of the New Testament Thomas R. Yoder Neufeld 2007 ISBN 1-58743-202-1 p. 111

- ^ a b Essays in New Testament interpretation by Charles Francis Digby Moule 1982 ISBN 0-521-23783-1 p. 63

- ^ a b The Melody of Faith: Theology in an Orthodox Key by Vigen Guroian 2010 ISBN 0-8028-6496-1 p. 28

- ^ Scripture in tradition by John Breck 2001 ISBN 0-88141-226-0 p. 12

- ^ a b c Redford, Douglas. The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels, 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pp. 117–130

- ^ a b c d Christianity:くぁ an introduction by Alister E. McGrath 2006 ISBN 978-1-4051-0901-7 pp. 16–22

- ^ a b c d The Christology of Mark's Gospel by Jack Dean Kingsbury 1983 ISBN 0-8006-2337-1 pp. 91–95

- ^ a b c d The Cambridge companion to the Gospels by Stephen C. Barton ISBN 0-521-00261-3 pp. 132–133

- ^ a b St Mark's Gospel and the Christian faith by Michael Keene 2002 ISBN 0-7487-6775-4 pp. 24–25

- ^ The people's New Testament commentary by M. Eugene Boring, Fred B. Craddock 2004 ISBN 0-664-22754-6 pp. 256–258

- ^ The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew-Luke, Volume 1 by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0-7814-3868-3 pp. 381–395

- ^ a b All the Apostles of the Bible by Herbert Lockyer 1988 ISBN 0-310-28011-7 pp. 106–111

- ^ a b The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 p. 114

- ^ a b Paul L. Maier "The Date of the Nativity and Chronology of Jesus" in Chronos, kairos, Christos: nativity and chronological studies by Jerry Vardaman, Edwin M. Yamauchi 1989 ISBN 0-931464-50-1 pp. 113–129

- ^ Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times by Paul Barnett 2002 ISBN 0-8308-2699-8 pp. 19–21

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (1993). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin Books. pp. 11, 249. ISBN 9780140144994.

- ^ a b The Gospel according to Matthew by Leon Morris ISBN 0-85111-338-9 p. 71

- ^ a b A theology of the New Testament by George Eldon Ladd 1993 [ISBN missing] p. 324

- ^ a b The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pp. 143–160

- ^ a b Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 pp. 97–110

- ^ a b The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pp. 165–180

- ^ a b Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 pp. 121–135

- ^ a b The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pp. 189–207

- ^ a b c Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 p. 137

- ^ a b c The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pp. 211–229

- ^ a b c d Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 p. 929

- ^ a b c d e Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 pp. 155–170

- ^ a b c Matthew by David L. Turner 2008 ISBN 0-8010-2684-9 p. 613

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 4 by Erwin Fahlbusch, 2005 ISBN 978-0-8028-2416-5 pp. 52–56

- ^ "1 Corinthians 15 NIV". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ Jesus in the Synagogue of Capernaum: The Pericope and its Programmatic Character for the Gospel of Mark by John Chijioke Iwe 1991 ISBN 978-8876528460 p. 7

- ^ The Sermon on the mount: a theological investigation by Carl G. Vaught 2001 ISBN 978-0-918954-76-3 pp. xi–xiv

- ^ The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke by Ján Majerník, Joseph Ponessa, Laurie Watson Manhardt, 2005, ISBN 1-931018-31-6, pp. 63–68

- ^ Medieval art: a topical dictionary by Leslie Ross 1996 ISBN 978-0-313-29329-0 p. 30

- ^ Jesus of history, Christ of faith by Thomas Zanzig 2000 ISBN 0-88489-530-0 p. 118

- ^ The Gospel and Epistles of John: A Concise Commentary by Raymond Edward Brown 1988 ISBN 978-0-8146-1283-5 pp. 25–27

- ^ a b c Harrington, Daniel J., SJ. "Jesus Goes Public." America, Jan. 7–14, 2008, pp. 38ff

- ^ Mt 3:13–17, 2 Cor. 5:21; Hebrews 4:15; 1 Peter 3:18

- ^ Pope Benedict XVI. Jesus of Nazareth. Doubleday Religion, 2007. ISBN 978-0-385-52341-7

- ^ Mt 3:17, Mk 1:11, Lk 3:21–22

- ^ The Gospel of Matthew by Daniel J. Harrington 1991 ISBN 0-8146-5803-2 p. 63

- ^ Christianity: A Biblical, Historical, and Theological Guide by Glenn Jonas, Kathryn Muller Lopez 2010 [ISBN missing] pp. 95–96

- ^ Studying the historical Jesus: evaluations of the state of current research by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 ISBN 90-04-11142-5 pp. 187–198

- ^ Jesus as a figure in history: how modern historians view the man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell 1998 ISBN 0-664-25703-8 p. 47

- ^ a b Jesus Remembered by James D. G. Dunn 2003 ISBN 0-8028-3931-2 p. 339

- ^ Matthew 4:1–11, New International Version

- ^ Mark 1:12–13, NIV

- ^ Luke 4:1–13, NIV

- ^ The Gospel according to Matthew by Leon Morris 1992 ISBN 0-85111-338-9 p. 83

- ^ Luke by Fred B. Craddock 1991 ISBN 0-8042-3123-0 p. 69

- ^ The beginning of the Gospel: introducing the Gospel according to Mark by Eugene LaVerdiere 1999 ISBN 0-8146-2478-2 p. 49

- ^ "Luke 5:1–11, New International Version". Biblegateway. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- ^ John Clowes, The Miracles of Jesus Christ published by J. Gleave, Manchester, UK, 1817, p. 214, available on Google books

- ^ The Gospel of Luke by Timothy Johnson, Daniel J. Harrington, 1992 ISBN 0-8146-5805-9 p. 89

- ^ The Gospel of Luke, by Joel B. Green 1997 ISBN 0-8028-2315-7 p. 230

- ^ John by Gail R. O'Day, Susan Hylen 2006 ISBN 0-664-25260-5 p. 31

- ^ H. Van der Loos, 1965 The Miracles of Jesus, E.J. Brill Press, Netherlands page 599

- ^ Dmitri Royster 1999 The miracles of Christ ISBN 0-88141-193-0 p. 71

- ^ The Gospel according to Matthew: an introduction and commentary by R. T. France 1987 ISBN 0-8028-0063-7 p. 154

- ^ Michael Keene 2002 St Mark's Gospel and the Christian faith ISBN 0-7487-6775-4 p. 26

- ^ John Clowes, 1817 The Miracles of Jesus Christ published by J. Gleave, Manchester, UK p. 47

- ^ The Gospel of Matthew by R. T. France 2007 ISBN 0-8028-2501-X p. 349

- ^ The first gospel by Harold Riley, 1992 ISBN 0-86554-409-3 p. 47

- ^ Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 p. 48

- ^ The life of Jesus by David Friedrich Strauss, 1860 published by Calvin Blanchard, p. 340

- ^ Luke by Sharon H. Ringe 1995 ISBN 0-664-25259-1 pp. 151–152

- ^ Robert Maguire 1863 The miracles of Christ published by Weeks and Co. London p. 185

- ^ Merrill Chapin Tenney 1997 John: Gospel of Belief ISBN 0-8028-4351-4 p. 114

- ^ Dwight Pentecost 2000 The words and works of Jesus Christ ISBN 0-310-30940-9 p. 234

- ^ Jesus the miracle worker: a historical & theological study by Graham H. Twelftree 1999 ISBN 0-8308-1596-1 p. 79

- ^ a b Jesus the miracle worker: a historical & theological study by Graham H. Twelftree 1999 ISBN 0-8308-1596-1 pp. 133–134

- ^ Berard L. Marthaler 2007 The creed: the apostolic faith in contemporary theology ISBN 0-89622-537-2 p. 220

- ^ Lockyer, Herbert, 1988 All the Miracles of the Bible ISBN 0-310-28101-6 p. 235

- ^ Lamar Williamson 1983 Mark ISBN 0-8042-3121-4 pp. 138–140

- ^ a b The Collegeville Bible Commentary: New Testament by Robert J. Karris 1992 ISBN 0-8146-2211-9 pp. 885–886

- ^ a b Who do you say that I am? Essays on Christology by Jack Dean Kingsbury, Mark Allan Powell, David R. Bauer 1999 ISBN 0-664-25752-6 p. xvi

- ^ Christology and the New Testament by Christopher Mark Tuckett 2001 ISBN 0-664-22431-8 p. 109

- ^ The people's New Testament commentary by M. Eugene Boring, Fred B. Craddock 2004 ISBN 0-664-22754-6 p. 69

- ^ a b One teacher: Jesus' teaching role in Matthew's gospel by John Yueh-Han Yieh 2004 ISBN 3-11-018151-7 pp. 240–241

- ^ The Gospel of Matthew by Rudolf Schnackenburg 2002 ISBN 0-8028-4438-3 pp. 7–9

- ^ Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth. Bloomsbury. pp. 188–189.

- ^ a b c Transfiguration by Dorothy A. Lee 2005 ISBN 978-0-8264-7595-4 pp. 21–30

- ^ a b Lockyer, Herbert, 1988 All the Miracles of the Bible ISBN 0-310-28101-6 p. 213

- ^ Clowes, John, 1817, The Miracles of Jesus Christ published by J. Gleave, Manchester, UK p. 167

- ^ Henry Rutter, Evangelical harmony Keating and Brown, London 1803. p. 450

- ^ Karl Barth Church dogmatics ISBN 0-567-05089-0 p. 478

- ^ Nicholas M. Healy, 2003 Thomas Aquinas: theologian of the Christian life ISBN 978-0-7546-1472-2 p. 100

- ^ Transfiguration by Dorothy A. Lee 2005 ISBN 978-0-8264-7595-4 p. 2

- ^ The temptations of Jesus in Mark's Gospel by Susan R. Garrett 1996 ISBN 978-0-8028-4259-6 pp. 74–75

- ^ Matthew for Everyone by Tom Wright 2004 ISBN 0-664-22787-2 p. 9

- ^ Big Picture of the Bible – New Testament by Lorna Daniels Nichols 2009 ISBN 1-57921-928-4 p. 12

- ^ John by Gerard Stephen Sloyan 1987 ISBN 0-8042-3125-7 p. 11

- ^ Preaching Matthew's Gospel by Richard A. Jensen 1998 ISBN 978-0-7880-1221-1 pp. 25 & 158

- ^ a b c Behold the King: A Study of Matthew by Stanley D. Toussaint 2005 ISBN 0-8254-3845-4 pp. 215–216

- ^ a b Matthew by Larry Chouinard 1997 ISBN 0-89900-628-0 p. 321

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pp. 312–313

- ^ Francis J. Moloney, Daniel J. Harrington, 1998 The Gospel of John Liturgical Press ISBN 0-8146-5806-7 p. 325

- ^ Gospel figures in art by Stefano Zuffi 2003 ISBN 978-0-89236-727-6 pp. 254–259

- ^ Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 pp. 224–229

- ^ Cox (2007) p. 182

- ^ Craig A. Evans 2005 The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: John's Gospel, Hebrews-Revelation ISBN 0-7814-4228-1 p. 122

- ^ The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke by Ján Majerník, Joseph Ponessa, Laurie Watson Manhardt 2005 ISBN 1-931018-31-6 page 169

- ^ a b c d e f The Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament edited by John F. Walvoord, Roy B. Zuck 1983 ISBN 978-0-88207-812-0 pages 83–85

- ^ a b c d e The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew-Luke, Volume 1 by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0-7814-3868-3 page 487-500

- ^ Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament Doubleday 1997 ISBN 0-385-24767-2, p. 146.

- ^ a b Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0-8054-4482-3 pages 396–400

- ^ a b c Holman Concise Bible Dictionary 2011 ISBN 0-8054-9548-7 pages 608–609

- ^ a b The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1982 ISBN 0-8028-3782-4 pages 1050–1052

- ^ Pontius Pilate: portraits of a Roman governor by Warren Carter 2003 ISBN 978-0-8146-5113-1 pages 120–121

- ^ New Testament History by Richard L. Niswonger 1992 ISBN 0-310-31201-9 page 172

- ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995), International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. vol. K-P. p. 929.

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1982 vol. K-P, p. 979.

- ^ Bond, Helen Katharine (1998). Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-521-63114-3.

- ^ Matthew (New Cambridge Bible Commentary) by Craig A. Evans (Feb 6, 2012) ISBN 0521812143 page 454

- ^ The Historical Jesus Through Catholic and Jewish Eyes by Bryan F. Le Beau, Leonard J. Greenspoon and Dennis Hamm (Nov 1, 2000) ISBN 1563383225 pages 105–106

- ^ Funk, Robert W.; Jesus Seminar (1998). The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. San Francisco: Harper.

- ^ John Dominic Crossan, (1995) Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography HarperOne ISBN 0-06-061662-8 page 145. J. D. Crossan, page 145 states: "that he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be."

- ^ The Word in this world by Paul William Meyer, John T. Carroll 2004 ISBN 0-664-22701-5 page 112

- ^ a b c d e f g The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew-Luke, Volume 1 by Craig A. Evans 2003 ISBN 0-7814-3868-3 page 509-520

- ^ a b c d e The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pages 211–214

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions by Merriam-Webster, Inc. 1999 ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0 page 271

- ^ a b Geoffrey W. Bromiley, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Eerdmans Press 1995, ISBN 0-8028-3784-0 page 426

- ^ Joseph F. Kelly, An Introduction to the New Testament 2006 ISBN 978-0-8146-5216-9 page 153

- ^ Jesus: the complete guide by Leslie Houlden 2006 ISBN 0-8264-8011-X page 627

- ^ Vernon K. Robbins in Literary studies in Luke-Acts by Richard P. Thompson (editor) 1998 ISBN 0-86554-563-4 pages 200–201

- ^ Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 page 648

- ^ Reading Luke-Acts: dynamics of Biblical narrative by William S. Kurz 1993 ISBN 0-664-25441-1 page 201

- ^ The Gospel according to Mark by George Martin 2o05 ISBN 0-8294-1970-5 page 440

- ^ Mark by Allen Black 1995 ISBN 0-89900-629-9 page 280

- ^ The Gospel of Matthew by Daniel J. Harrington 1991 ISBN 0-8146-5803-2 page 404

- ^ The Gospel according to Matthew by Leon Morris ISBN 0-85111-338-9 page 727

- ^ For example, compare: "It was nine in the morning when they crucified him." (Mark 15:25 NIV) and "It was the day of Preparation of the Passover; it was about noon. (...) Finally Pilate handed him over to them to be crucified." (John 19:14,16 NIV). Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium (1999), p. 32–36.

- ^ Matthew 28:1, Mark 16:9, Luke 24:1 and John 20:1

- ^ a b c d e Cox (2007) pp. 216–226

- ^ a b c Stagg, Evalyn and Frank. Woman in the World of Jesus. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1978, p. 144–150.

- ^ Vladimir Lossky, 1982 The Meaning of Icons ISBN 978-0-913836-99-6 page 185

- ^ Mark 16:1–8, Matthew 28:1–8, Luke 24:1–12, and John 20:1–13

- ^ Setzer, Claudia. "Excellent Women: Female Witness to the Resurrection." Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 116, No. 2 (Summer, 1997), pp. 259–272

- ^ Catholic Comparative New Testament by Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-528299-X page 589

- ^ "Ascension, The." Macmillan Dictionary of the Bible. London: Collins, 2002. Credo Reference. Web. 27 September 2010. ISBN 0333648056

- ^ Fred B. Craddock, Luke (Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), p. 293

- ^ Luke by Fred B. Craddock 2009 ISBN 0664234356 pages 293–294

- ^ a b New Testament Theology by Frank J. Matera 2007 ISBN 066423044X pages 53–54

- ^ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible by D. N. Freedman, David Noel, Allen Myers and Astrid B. Beck 2000 ISBN 9053565035 page 110

References

[edit]- Cox, Steven L.; Easley, Kendell H (2007). Harmony of the Gospels. ISBN 978-0-8054-9444-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Bruce J. Malina: Windows on the World of Jesus: Time Travel to Ancient Judea. Westminster John Knox Press: Louisville (Kentucky) 1993

- Bruce J. Malina: The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology. 3rd edition, Westminster John Knox Press Louisville (Kentucky) 2001

- Ekkehard Stegemann and Wolfgang Stegemann: The Jesus Movement: A Social History of Its First Century. Augsburg Fortress Publishers: Minneapolis 1999

- Shailer Mathews (1899). A History of New Testament Times in Palestine.

External links

[edit] Media related to Life of Jesus in the New Testament at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Life of Jesus in the New Testament at Wikimedia Commons