Xiongnu

Xiongnu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd century BC–2nd century AD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

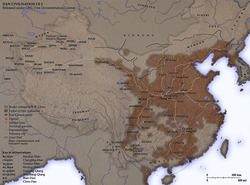

Territory of the Xiongnu in the 2nd century BC (before the Han–Xiongnu War of 133 BC – 89 AD): it includes Mongolia, east Kazakhstan, east Kyrgyzstan, south Siberia, and parts of northern China such as western Manchuria, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Gansu.[1][2][3][4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Longcheng[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | various | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Shamanism, Tengrism, Buddhism[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Xiongnu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Tribal confederation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chanyu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 220 - 209 BCE | Touman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 209 - 174 BCE | Modu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 174 - 161 BCE | Laoshang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 46 AD | Wudadihou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 3rd century BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 2nd century AD | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Xiongnu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 匈奴 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

|

The Xiongnu (Chinese: 匈奴,[9] [ɕjʊ́ŋ.nǔ]) were a tribal confederation[10] of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 209 BC, founded the Xiongnu Empire.[11]

After overthrowing their previous overlords,[12] the Yuezhi, the Xiongnu became the dominant power on the steppes of East Asia, centred on the Mongolian Plateau. The Xiongnu were also active in areas now part of Siberia, Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Xinjiang. Their relations with adjacent Chinese dynasties to the south-east were complex—alternating between various periods of peace, war, and subjugation. Ultimately, the Xiongnu were defeated by the Han dynasty in a centuries-long conflict, which led to the confederation splitting in two, and forcible resettlement of large numbers of Xiongnu within Han borders. During the Sixteen Kingdoms era, listed as one of the "Five Barbarians", their descendants founded the dynastic states of Han-Zhao, Northern Liang and Helian Xia in northern China.

Attempts to associate the Xiongnu with the nearby Sakas and Sarmatians were once controversial. However, archaeogenetics has confirmed their interaction with the Xiongnu, and also possibly their relation to the Huns. The identity of the ethnic core of Xiongnu has been a subject of varied hypotheses, because only a few words, mainly titles and personal names, were preserved in the Chinese sources. The name Xiongnu may be cognate with that of the Huns and/or the Huna,[13][14][15] although this is disputed.[16][17] Other linguistic links—all of them also controversial—proposed by scholars include Turkic,[18][19][20][21][22][23] Iranian,[24][25][26] Mongolic,[27] Uralic,[28] Yeniseian,[16][29][30][31] or multi-ethnic.[32]

Name

The pronunciation of 匈奴 as Xiōngnú [ɕjʊ́ŋnǔ] is the modern Mandarin Chinese pronunciation, from the Mandarin dialect spoken now in Beijing, which came into existence less than 1,000 years ago. The Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *xiuoŋ-na or *qhoŋna.[33] Sinologist Axel Schuessler (2014) reconstructs the pronunciations of 匈奴 as *hoŋ-nâ in Late Old Chinese (c. 318 BCE) and as *hɨoŋ-nɑ in Eastern Han Chinese; citing other Chinese transcriptions wherein the velar nasal medial -ŋ-, after a short vowel, seemingly played the role of a general nasal – sometimes equivalent to n or m –, Schuessler proposes that 匈奴 Xiongnu < *hɨoŋ-nɑ < *hoŋ-nâ might be a Chinese rendition, Han or even pre-Han, of foreign *Hŏna or *Hŭna, which Schuessler compares to Huns and Sanskrit Hūṇā.[15] However, the same medial -ŋ- prompts Christopher P. Atwood (2015) to reconstruct *Xoŋai, which he derives from the Ongi River (Mongolian: Онги гол) in Mongolia and suggests that it was originally a dynastic name rather than an ethnic name.[34]

History

Predecessors

The territories associated with the Xiongnu in central/east Mongolia were previously inhabited by the Slab Grave Culture (Ancient Northeast Asian origin), which persisted until the 3rd century BC.[36] Genetic research indicates that the Slab Grave people were the primary ancestors of the Xiongnu, and that the Xiongnu formed through substantial and complex admixture with West Eurasians.[37]

During the Western Zhou (1045–771 BC), there were numerous conflicts with nomadic tribes from the north and the northwest, variously known as the Xianyun, Guifang, or various "Rong" tribes, such as the Xirong, Shanrong or Quanrong.[38] These tribes are recorded as harassing Zhou territory, but at the time the Zhou were expanding northwards, encroaching on their traditional lands, especially into the Wei River valley. Archaeologically, the Zhou expanded to the north and the northwest at the expense of the Siwa culture.[38] The Quanrong put an end to the Western Zhou in 771 BC, sacking the Zhou capital of Haojing and killing the last Western Zhou king You.[38] Thereafter the task of dealing with the northern tribes was left to their vassal, the Qin state.[38]

To the west, the Pazyryk culture (6th-3rd century BC) immediately preceded the formation of the Xiongnus.[39] A Scythian culture,[40] it was identified by excavated artifacts and mummified humans, such as the Siberian Ice Princess, found in the Siberian permafrost, in the Altay Mountains, Kazakhstan and nearby Mongolia.[41] To the south, the Ordos culture had developed in the Ordos Loop (modern Inner Mongolia, China) during the Bronze and early Iron Age from the 6th to 2nd centuries BC, and is of unknown ethno-linguistic origin, and is thought to represent the easternmost extension of Indo-European-speakers.[42][43][44] The Yuezhi were displaced by the Xiongnu expansion in the 2nd century BC, and had to migrate to Central and Southern Asia.[45][46]

Early history

Western Han historian Sima Qian composed an early yet detailed exposition on the Xiongnu in one liezhuan (arrayed account) of his Records of the Grand Historian (c. 100 BC), wherein the Xiongnu were alleged to be descendants of a certain Chunwei, who in turn descended from the "lineage of Lord Xia", a.k.a. Yu the Great.[50][51] Even so, Sima Qian also drew a distinct line between the settled Huaxia people (Han) to the pastoral nomads (Xiongnu), characterizing them as two polar groups in the sense of a civilization versus an uncivilized society: the Hua–Yi distinction.[52] Sima Qian also mentioned Xiongnu's early appearance north of Wild Goose Gate and Dai commanderies before 265 BCE, just before the Zhao-Xiongnu War;[53][54] however, sinologist Edwin Pulleyblank (1994) contends that pre-241-BCE references to the Xiongnu are anachronistic substitutions for the Hu people instead.[55][56] Sometimes the Xiongnu were distinguished from other nomadic peoples; namely, the Hu people;[57] yet on other occasions, Chinese sources often just classified the Xiongnu as a Hu people, which was a blanket term for nomadic people.[55][58] Even Sima Qian was inconsistent: in the chapter "Hereditary House of Zhao", he considered the Donghu to be the Hu proper,[59][60] yet elsewhere he considered Xiongnu to be also Hu.[61][55]

Ancient China often came in contact with the Xianyun and the Xirong nomadic peoples. In later Chinese historiography, some groups of these peoples were believed to be the possible progenitors of the Xiongnu people.[62] These nomadic people often had repeated military confrontations with the Shang and especially the Zhou, who often conquered and enslaved the nomads in an expansion drift.[62] During the Warring States period, the armies from the Qin, Zhao and Yan states were encroaching and conquering various nomadic territories that were inhabited by the Xiongnu and other Hu peoples.[63] The Zhao–Xiongnu War is a notable example of these campaigns.

Pulleyblank argued that the Xiongnu were part of a Xirong group called Yiqu, who had lived in Shaanbei and had been influenced by China for centuries, before they were driven out by the Qin ty.[64][65] Qin's campaign against the Xiongnu expanded Qin's territory at the expense of the Xiongnu.[66] After the unification of Qin dynasty, Xiongnu was a threat to the northern board of Qin. They were likely to attack the Qin dynasty when they suffered natural disasters.[67]

State formation

The first known Xiongnu leader was Touman, who reigned between 220-209 BC. In 215 BC, Chinese Emperor Qin Shi Huang sent General Meng Tian on a military campaign against the Xiongnu. Meng Tian defeated the Xiongnu and expelled them from the Ordos loop, forcing Touman and the Xiongnu to flee north into the Mongolian Plateau.[68] In 210 BC, Meng Tian died, and in 209 BC, Touman's son Modu became the Xiongnu Chanyu.

In order to protect the Xiongnu from the threat of the Qin dynasty, Modu Chanyu united the Xiongnu into a powerful confederation.[66] This transformed the Xiongnu into a more formidable polity, able to form larger armies and exercise improved strategic coordination. Two years later, in 207 BC, the Qin dynasty fell, and after a period of internal conflict, it was replaced by the Western Han dynasty in 202 BC. This period of Chinese instability was a time of prosperity for the Xiongnu, who adopted many Han agriculture techniques such as slaves for heavy labor and lived in Han-style homes.[69]

After forging internal unity, Modu Chanyu expanded the Xiongnu empire in all directions. To the north he conquered a number of nomadic peoples, including the Dingling of southern Siberia. He crushed the power of the Donghu people of eastern Mongolia and Manchuria as well as the Yuezhi in the Hexi Corridor of Gansu, where his son, Jizhu, made a skull cup out of the Yuezhi king. Modu also retook the original homeland of Xiongnu on the Yellow River, which had previously been taken by the Qin general Meng Tian.[71] Under Modu's leadership, the Xiongnu became so strong that they began to threaten the Han dynasty.

In 200 BC, Modu besieged the first Han dynasty emperor Gaozu (Gao-Di) with his 320,000-strong army at Peteng Fortress in Baideng (present-day Datong, Shanxi).[72] Gaozu (Gao-Di) after agreed to all Modu's terms, such as ceding the northern provinces to the Xiongnu and paying annual taxes, he was allowed to leave the siege. Although Gaozu was able to return to his capital Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), Modu occasionally threatened the Han's northern frontier and finally in 198 BC, a peace treaty was settled.

Xiongnu in their expansion drove their western neighbour Yuezhi from the Hexi Corridor in year 176 BC, killing the Yuezhi king and asserting their presence in the Western Regions.[13]

By the time of Modu's death in 174 BC, the Xiongnu were recognized as the most prominent of the nomads bordering the Chinese Han empire[72] According to the Book of Han, later quoted in Duan Chengshi's ninth-century Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang:

Also, according to the Han shu, Wang Wu (王烏) and others were sent as envoys to pay a visit to the Xiongnu. According to the customs of the Xiongnu, if the Han envoys did not remove their tallies of authority, and if they did not allow their faces to be tattooed, they could not gain entrance into the yurts. Wang Wu and his company removed their tallies, submitted to tattoo, and thus gained entry. The Shanyu looked upon them very highly.[73]

Xiongnu hierarchy

The ruler of the Xiongnu was called the Chanyu.[76] Under him were the Tuqi Kings.[76] The Tuqi King of the Left was normally the heir presumptive.[76] Next lower in the hierarchy came more officials in pairs of left and right: the guli, the army commanders, the great governors, the danghu and the gudu. Beneath them came the commanders of detachments of one thousand, of one hundred, and of ten men. This nation of nomads, a people on the march, was organized like an army.[77]

After Modu, later leaders formed a dualistic system of political organisation with the left and right branches of the Xiongnu divided on a regional basis. The chanyu or shanyu, a ruler equivalent to the Emperor of China, exercised direct authority over the central territory. Longcheng (around the Khangai Mountains, Otuken)[78][79] (Chinese: 龍城; Mongolian: Luut; lit. "Dragon City") became the annual meeting place and served as the Xiongnu capital.[5] The ruins of Longcheng were found south of Ulziit District, Arkhangai Province in 2017.[80]

North of Shanxi with the Tuqi King of the Left was holding the area north of Beijing and the Tuqi King of the Right was holding the Ordos Loop area as far as Gansu.[81] When the Xiongnu had been driven north, to today's Mongolia.

Marriage diplomacy with Han dynasty

In the winter of 200 BC, following a Xiongnu siege of Taiyuan, Emperor Gaozu of Han personally led a military campaign against Modu Chanyu. At the Battle of Baideng, he was ambushed, reputedly by Xiongnu cavalry. The emperor was cut off from supplies and reinforcements for seven days, only narrowly escaping capture.

The Han dynasty sent random unrelated commoner women falsely labeled as "princesses" and members of the Han imperial family multiple times when they were practicing Heqin marriage alliances with the Xiongnu in order to avoid sending the emperor's daughters.[82][83][84][85][86] The Han sent these "princesses" to marry Xiongnu leaders in their efforts to stop the border raids. Along with arranged marriages, the Han sent gifts to bribe the Xiongnu to stop attacking.[72] After the defeat at Pingcheng in 200 BC, the Han emperor abandoned a military solution to the Xiongnu threat. Instead, in 198 BC , the courtier Liu Jing was dispatched for negotiations. The peace settlement eventually reached between the parties included a Han princess given in marriage to the chanyu (called heqin) (Chinese: 和親; lit. 'harmonious kinship'); periodic gifts to the Xiongnu of silk, distilled beverages and rice; equal status between the states; and a boundary wall as mutual border.

This first treaty set the pattern for relations between the Han and the Xiongnu for sixty years. Up to 135 BC, the treaty was renewed nine times, each time with an increase in the "gifts" to the Xiongnu Empire. In 192 BC, Modun even asked for the hand of Emperor Gaozu of Han widow Empress Lü Zhi. His son and successor, the energetic Jiyu, known as the Laoshang Chanyu, continued his father's expansionist policies. Laoshang succeeded in negotiating with Emperor Wen terms for the maintenance of a large scale government sponsored market system.

While the Xiongnu benefited handsomely, from the Chinese perspective marriage treaties were costly, very humiliating and ineffective. Laoshang Chanyu showed that he did not take the peace treaty seriously. On one occasion his scouts penetrated to a point near Chang'an. In 166 BC he personally led 140,000 cavalry to invade Anding, reaching as far as the imperial retreat at Yong. In 158 BC, his successor sent 30,000 cavalry to attack Shangdang and another 30,000 to Yunzhong.[citation needed]

The Xiongnu also practiced marriage alliances with Han dynasty officers and officials who defected to their side by marrying off sisters and daughters of the Chanyu (the Xiongnu ruler) to Han Chinese who joined the Xiongnu and Xiongnu in Han service. The daughter of the Laoshang Chanyu (and older sister of Junchen Chanyu and Yizhixie Chanyu) was married to the Xiongnu General Zhao Xin, the Marquis of Xi who was serving the Han dynasty. The daughter of Qiedihou Chanyu was married to the Han Chinese General Li Ling after he surrendered and defected.[92][93][94][95][96] Another Han Chinese General who defected to the Xiongnu was Li Guangli, general in the War of the Heavenly Horses, who also married a daughter of the Hulugu Chanyu.[97] The Han Chinese diplomat Su Wu married a Xiongnu woman given by Li Ling when he was arrested and taken captive.[98] Han Chinese explorer Zhang Qian married a Xiongnu woman and had a child with her when he was taken captive by the Xiongnu.[99][100][101][102][103][104][105]

The Yenisei Kyrgyz khagans of the Yenisei Kyrgyz Khaganate claimed descent from the Chinese general Li Ling, grandson of the famous Han dynasty general Li Guang.[106][107][108][109] Li Ling was captured by the Xiongnu and defected in the first century BCE.[110][111] And since the Tang royal Li family also claimed descent from Li Guang, the Kirghiz Khagan was therefore recognized as a member of the Tang Imperial family. This relationship soothed the relationship when Kyrgyz khagan Are (阿熱) invaded Uyghur Khaganate and put Qasar Qaghan to the sword. The news brought to Chang'an by Kyrgyz ambassador Zhuwu Hesu (註吾合素).

Han–Xiongnu war

The Han dynasty made preparations for war when the Han Emperor Wu dispatched the Han Chinese explorer Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and to form an alliance with the Yuezhi people in order to combat the Xiongnu. During this time Zhang married a Xiongnu wife, who bore him a son, and gained the trust of the Xiongnu leader.[99][112][113][102][103][114][105] While Zhang Qian did not succeed in this mission,[115] his reports of the west provided even greater incentive to counter the Xiongnu hold on westward routes out of the Han Empire, and the Han prepared to mount a large scale attack using the Northern Silk Road to move men and material.

While the Han dynasty was making preparations for a military confrontation since the reign of Emperor Wen, the break did not come until 133 BC, following an abortive trap to ambush the chanyu at Mayi. By that point the empire was consolidated politically, militarily and economically, and was led by an adventurous pro-war faction at court. In that year, Emperor Wu reversed the decision he had made the year before to renew the peace treaty.

Full-scale war broke out in autumn 129 BC, when 40,000 Han cavalry made a surprise attack on the Xiongnu at the border markets. In 127 BC, the Han general Wei Qing retook the Ordos. In 121 BC, the Xiongnu suffered another setback when Huo Qubing led a force of light cavalry westward out of Longxi and within six days fought his way through five Xiongnu kingdoms. The Xiongnu Hunye king was forced to surrender with 40,000 men. In 119 BC both Huo and Wei, each leading 50,000 cavalrymen and 100,000 footsoldiers (in order to keep up with the mobility of the Xiongnu, many of the non-cavalry Han soldiers were mobile infantrymen who traveled on horseback but fought on foot), and advancing along different routes, forced the chanyu and his Xiongnu court to flee north of the Gobi Desert.[116]

Major logistical difficulties limited the duration and long-term continuation of these campaigns. According to the analysis of Yan You (嚴尤), the difficulties were twofold. Firstly there was the problem of supplying food across long distances. Secondly, the weather in the northern Xiongnu lands was difficult for Han soldiers, who could never carry enough fuel.[a] According to official reports, the Xiongnu lost 80,000 to 90,000 men, and out of the 140,000 horses the Han forces had brought into the desert, fewer than 30,000 returned to the Han Empire.

In 104 and 102 BC, the Han fought and won the War of the Heavenly Horses against the Kingdom of Dayuan. As a result, the Han gained many Ferghana horses which further aided them in their battle against the Xiongnu. As a result of these battles, the Han Empire controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They succeeded in separating the Xiongnu from the Qiang peoples to the south, and also gained direct access to the Western Regions. Because of strong Han control over the Xiongnu, the Xiongnu became unstable and were no longer a threat to the Han Empire.[121]

Ban Chao, Protector General (都護; Duhu) of the Han dynasty, embarked with an army of 70,000 soldiers in a campaign against the Xiongnu remnants who were harassing the trade route now known as the Silk Road. His successful military campaign saw the subjugation of one Xiongnu tribe after another. Ban Chao also sent an envoy named Gan Ying to Daqin (Rome). Ban Chao was created the Marquess of Dingyuan (定遠侯, i.e., "the Marquess who stabilized faraway places") for his services to the Han Empire and returned to the capital Luoyang at the age of 70 years and died there in the year 102. Following his death, the power of the Xiongnu in the Western Regions increased again, and the emperors of subsequent dynasties did not reach as far west until the Tang dynasty.[122]

Xiongnu Civil War (60–53 BC)

When a Chanyu died, power could pass to his younger brother if his son was not of age. This system, which can be compared to Gaelic tanistry, normally kept an adult male on the throne, but could cause trouble in later generations when there were several lineages that might claim the throne. When the 12th Chanyu died in 60 BC, power was taken by Woyanqudi, a grandson of the 12th Chanyu's cousin. Being something of a usurper, he tried to put his own men in power, which only increased the number of his enemies. The 12th Chanyu's son fled east and, in 58 BC, revolted. Few would support Woyanqudi and he was driven to suicide, leaving the rebel son, Huhanye, as the 14th Chanyu. The Woyanqudi faction then set up his brother, Tuqi, as Chanyu (58 BC). In 57 BC three more men declared themselves Chanyu. Two dropped their claims in favor of the third who was defeated by Tuqi in that year and surrendered to Huhanye the following year. In 56 BC Tuqi was defeated by Huhanye and committed suicide, but two more claimants appeared: Runzhen and Huhanye's elder brother Zhizhi Chanyu. Runzhen was killed by Zhizhi in 54 BC, leaving only Zhizhi and Huhanye. Zhizhi grew in power, and, in 53 BC, Huhanye moved south and submitted to the Chinese. Huhanye used Chinese support to weaken Zhizhi, who gradually moved west. In 49 BC, a brother to Tuqi set himself up as Chanyu and was killed by Zhizhi. In 36 BC, Zhizhi was killed by a Chinese army while trying to establish a new kingdom in the far west near Lake Balkhash.

Tributary relations with the Han

In 53 BC Huhanye (呼韓邪) decided to enter into tributary relations with Han China.[124] The original terms insisted on by the Han court were that, first, the Chanyu or his representatives should come to the capital to pay homage; secondly, the Chanyu should send a hostage prince; and thirdly, the Chanyu should present tribute to the Han emperor. The political status of the Xiongnu in the Chinese world order was reduced from that of a "brotherly state" to that of an "outer vassal" (外臣).

Huhanye sent his son, the "wise king of the right" Shuloujutang, to the Han court as hostage. In 51 BC he personally visited Chang'an to pay homage to the emperor on the Lunar New Year. In the same year, another envoy Qijushan (稽居狦) was received at the Ganquan Palace in the north-west of modern Shanxi.[125] On the financial side, Huhanye was amply rewarded in large quantities of gold, cash, clothes, silk, horses and grain for his participation. Huhanye made two further homage trips, in 49 BC and 33 BC; with each one the imperial gifts were increased. On the last trip, Huhanye took the opportunity to ask to be allowed to become an imperial son-in-law. As a sign of the decline in the political status of the Xiongnu, Emperor Yuan refused, giving him instead five ladies-in-waiting. One of them was Wang Zhaojun, famed in Chinese folklore as one of the Four Beauties.

When Zhizhi learned of his brother's submission, he also sent a son to the Han court as hostage in 53 BC. Then twice, in 51 BC and 50 BC, he sent envoys to the Han court with tribute. But having failed to pay homage personally, he was never admitted to the tributary system. In 36 BC, a junior officer named Chen Tang, with the help of Gan Yanshou, protector-general of the Western Regions, assembled an expeditionary force that defeated him at the Battle of Zhizhi and sent his head as a trophy to Chang'an.

Tributary relations were discontinued during the reign of Huduershi (18 AD–48), corresponding to the political upheavals of the Xin dynasty. The Xiongnu took the opportunity to regain control of the western regions, as well as neighboring peoples such as the Wuhuan. In 24 AD, Hudershi even talked about reversing the tributary system.

Southern Xiongnu and Northern Xiongnu

The Xiongnu's new power was met with a policy of appeasement by Emperor Guangwu. At the height of his power, Huduershi even compared himself to his illustrious ancestor, Modu. Due to growing regionalism among the Xiongnu, however, Huduershi was never able to establish unquestioned authority. In contravention of a principle of fraternal succession established by Huhanye, Huduershi designated his son Punu as heir-apparent. However, as the eldest son of the preceding chanyu, Bi (Pi)—the Rizhu King of the Right—had a more legitimate claim. Consequently, Bi refused to attend the annual meeting at the chanyu's court. Nevertheless, in 46 AD, Punu ascended the throne.

In 48 AD, a confederation of eight Xiongnu tribes in Bi's power base in the south, with a military force totalling 40,000 to 50,000 men, seceded from Punu's kingdom and acclaimed Bi as chanyu. This kingdom became known as the Southern Xiongnu.

Northern Xiongnu

The rump kingdom under Punu, around the Orkhon (modern north central Mongolia) became known as the Northern Xiongnu, with Punu, becoming known as the Northern Chanyu. In 49 AD, the Northern Xiongnu was dealt a heavy defeat to the Southern Xiongnu. That same year, Zhai Tong, a Han governor of Liaodong also enticed the Wuhuan and Xianbei into attacking the Northern Xiongnu.[127] Soon, Punu began sending envoys on several separate occasions to negotiate peace with the Han dynasty, but made little to no progress.

In the 60s, the Northern Xiongnu resumed hostilities as they attempted to expand their influence into the Western Regions and launched raids on the Han borders. In 73, the Han responded by sending Dou Gu and Geng Chong to lead a great expedition against the Northern Xiongnu in the Tarim Basin. The expedition, which saw the exploits of the general, Ban Chao, was initially successful, but the Han soon had to temporarily withdraw due to matters back home in 75.[128]

For the next decade, the Northern Xiongnu had to endure famines largely in part due to locust plagues. In 87, they suffered a major defeat to the Xianbei, who killed their chanyu Youliu and took his skin as a trophy. With the Northern Xiongnu in disarray, the Han general, Dou Xian launched an expedition and crushed them at the Battle of Ikh Bayan in 89. After another Han attack in 91, the Northern Chanyu fled with his followers to the northwest, never to be seen again, while the Northern Xiongnu that remained behind surrendered to the Han.[128]

In 94, dissatisfied with the newly appointed chanyu, the surrendered Northern Xiongnu rebelled and acclaimed Fenghou as their chanyu, who led them to flee outside the border. However, the separatist regime continued to face famines and the growing threat of the Xianbei, prompting 10,000 of them to return to Han in 96. Fenghou later sent envoys to Han intending to submit as a vassal but was rejected. The Northern Xiongnu were scattered, with most of them being absorbed the Xianbei. In 118, a defeated Fenghou brought around a mere 100 followers to surrender to Han.[128]

Remnants of the Northern Xiongnu held out in the Tarim Basin as they allied themselves with the Nearer Jushi Kingdom and captured Yiwu in 119. By 126, they were subjugated by the Han general, Ban Yong, while a branch led by a "Huyan King" (呼衍王) continued to resist. The Huyan King was last mentioned in 151 when he launched an attack on Yiwu but was driven away by Han forces. According to the fifth-century Book of Wei, the remnants of Northern Chanyu's tribe settled as Yueban (悅般), near Kucha and subjugated the Wusun; while the rest fled across the Altai mountains towards Kangju in Transoxania. It states that this group later became the Hephthalites.[129][130][131]

Southern Xiongnu

Coincidentally, the Southern Xiongnu were plagued by natural disasters and misfortunes—in addition to the threat posed by Punu. Consequently, in 50 AD, the Southern Xiongnu submitted to tributary relations with Han China. The system of tribute was considerably tightened by the Han, to keep the Southern Xiongnu under control. The chanyu was ordered to establish his court in the Meiji district of Xihe Commandery and the Southern Xiongnu were resettled in eight frontier commanderies. At the same time, large numbers of Chinese were also resettled in these commanderies, in mixed Han-Xiongnu settlements. Economically, the Southern Xiongnu became reliant on trade with the Han.

The Southern Xiongnu served as auxillaries to defend the northern borders for the Han and played a role in defeating the Northern Xiongnu. However, with the decline of their northern counterpart, the Southern Xiongnu continued to suffer the brunt of raids, this time by the Xianbei people of the steppe. In addition to the poor living conditions of the frontiers, the Chinese court would also interfere in the Southern Xiongnu's politics and install chanyus loyal to the Han. As a result, the Southern Xiongnu often rebelled, at times joining forces with the Wuhuan and receiving support from the Xianbei. Meanwhile, the Xiuchuge people, a branch of Xiongnu within China not attached to the Southern Xiongnu, was gaining momentum during the mid-2nd century.

During the late 2nd century AD, the Southern Xiongnu were drawn into the rebellions then plaguing the Han court. In 188, the chanyu sent troops to help the Han suppress a rebellion in Hebei—many of the Xiongnu feared that it would set a precedent for unending military service to the Han court. At the time, the Xiuchuge had rebel in Bing province and kill the Chinese provincial inspector. The rebellious faction among the Southern Xiongnu allied with the Xiuchuge and killed their chanyu as well. His son Yufuluo, entitled Chizhisizhu (持至尸逐侯), succeeded him, but was then overthrown by the rebels in 189. He travelled to Luoyang (the Han capital) to seek aid from the Han court, but at this time the Han court was in disorder from the clash between Grand General He Jin and the eunuchs, and the intervention of the warlord Dong Zhuo. The chanyu had no choice but to settle down with his followers around Pingyang, south of the Fen River in Shanxi. In 195, he died and was succeeded as chanyu by his brother Huchuquan.

North of the Fen River, the rebels prevented Yufuluo and his family from returning to their home. They initially elected a marquis of the Xubu clan as the new chanyu, but after his death, a nominal king was put in his place. While the other tribes appear to distant themselves from the ongoing Han civil war, the Xiuchuge remained active. In the 190s, the Xiuchuge allied themselves with the Heishan bandits of the Taihang Mountains before retreating west as the warlords Cao Cao and Yuan Shao established control over the north. The Xiuchuge were eventually defeated by Cao Cao in 214.

In 215–216, Cao Cao detained Huchuquan in the city of Ye, and divided his followers in Shanxi into the Five Divisions (五部): left, right, south, north and centre. The office of chanyu was formally abolished, and the Southern Xiongnu were placed under the supervision of Yufuluo's uncle, Qubei. This was aimed at preventing the Xiongnu in Shanxi from engaging in rebellion, and also allowed Cao Cao to use them as auxiliaries in his cavalry. Each of the Five Divisions were supervised by a local chief, who in turn was under the "surveillance of a chinese resident", while the former chanyu was in "semicaptivity at the imperial court."[132]

Later Xiongnu states in northern China

Fang Xuanling's Book of Jin lists nineteen Xiongnu tribes that resettled within the Great Wall: Chuge (屠各), Xianzhi (鮮支), Koutou (寇頭), Wutan (烏譚), Chile (赤勒), Hanzhi (捍蛭), Heilang (黑狼), Chisha (赤沙), Yugang (鬱鞞), Weisuo (萎莎), Tutong (禿童), Bomie (勃蔑), Qiangqu (羌渠), Helai (賀賴), Zhongqin (鐘跂), Dalou (大樓), Yongqu (雍屈), Zhenshu (真樹) and Lijie (力羯). Among the nineteen tribes, the Chuge, also known as the Xiuchuge, were the most honored and prestigious.[133][128]

With the abolishment of the chanyu, the Xiongnu gradually ceased as a coherent identity. In Bing province, the Chuge identity eventually supplanted that of the Xiongnu among the Five Divisions, while those excluded from the group mingled with tribes from various ethnicities and were referred to as "hu" or other vague terms for the non-Chinese. Many of them began adopting Chinese family names such as Liu (劉), which was prevalent among the Five Divisions.[134] Nonetheless, the Xiongnu are classified as one of the "Five Barbarians" of the Sixteen Kingdoms period. The Han-Zhao and Helian Xia dynasties were both founded by rulers on the basis of their Xiongnu ancestry. The Northern Liang, established by the Lushuihu, is sometimes categorized as a Xiongnu state in recent historiographies. Shi Le, the founder of the Later Zhao dynasty, was a descendant of the Xiongnu Qiangqu tribe, although by his time, he and his people had become a separate ethnic group known as the Jie.

Han-Zhao dynasty (304–329)

Han (304–319)

Despite Cao Cao's effort, the Five Divisions eventually grew restless and attempted to restore themselves to power. The Commander of the Left Division, Liu Bao briefly unified them during the mid-3rd century before the Cao Wei and Western Jin courts intervened and forced them back into five. They began to stage revolts during the early Jin period, but it would not be until 304, amidst the War of the Eight Princes that weakened Jin power in northern China, that they made a crucial breakthrough.

Liu Yuan, the son of Liu Bao and a general serving under one of the Jin princes, was offered by the Five Divisions to become the leader of their rebellion. After deceiving his prince, Liu Yuan returned to Bing province and was acclaimed as the Grand Chanyu. Later that year, he declared himself the King of Han. Liu Yuan and his family members were from the Chuge, but he also claimed himself to be a direct descendant of the Southern Xiongnu chanyus and depicted his state as a continuation of the Han dynasty, citing that his alleged ancestors were married to Han princesses through heqin.[128][134] He allowed the Han Chinese and non-Chinese tribes to serve under him, and in 308, he elevated his title to Emperor of Han.

The Western Jin, devastated by war and natural disasters, was unable to stop the growing threat of Han, even more so after the ascension of Liu Cong to the Han throne. In 311, the Jin imperial army was annihilated by Han forces, and shortly after, the Jin capital Luoyang was sacked and Emperor Huai was captured in an event known as the Disaster of Yongjia. In 316, the Jin restoration in Chang'an, headed by Emperor Min, was also crushed by Han. After the fall of Chang'an, the remnants of Jin survived in the south at Jiankang as the Eastern Jin dynasty.[135]

Although Han enjoyed military success, it also suffered from internal strife under Liu Cong. Throughout his reign, Liu Cong faced dissidence from his own ministers, and so he empowered his consort kins and eunuchs to counter them. The Han court fell into a power struggle which ended in a bloody purge of the government. Liu Cong also failed to constrain Shi Le, a general of Jie ethnicity who effectively held the eastern parts of the empire. After Liu Cong's death in 318, his consort kin, Jin Zhun massacred the emperor and a large portion of the aristocracy before being defeated by a combined force led by Liu Cong's cousin, Liu Yao, and Shi Le.

Former Zhao (319–329)

Amidst Jin Zhun's rebellion, the Han loyalists that escaped the massacre acclaimed Liu Yao as the new emperor. In 319, he moved the capital from Pingyang to Chang'an and renamed the dynasty as Zhao. Unlike his predecessors, Liu Yao appealed more to his Xiongnu ancestry by honouring Modu Chanyu and distancing himself from the state's initial positioning of restoring the Han dynasty. However, this was not a break from Liu Yuan, as he continued to honor Liu Yuan and Liu Cong posthumously; it is hence known to historians collectively as Han-Zhao. That same year, Shi Le proclaimed independence and formed his own state of Zhao, challenging Liu Yao for hegemony over northern China. For this reason, Han-Zhao is also known to historians as the Former Zhao to distinguish it from Shi Le's Later Zhao.

Liu Yao retained control over the Guanzhong region and expanded his domain westward by campaigning against remnants of the Jin, Former Liang and Chouchi. Eventually, Liu Yao led his army to fight Later Zhao for control over Luoyang but was captured by Shi Le's forces in battle and executed in 329. Chang'an soon fell to Later Zhao and the last of Former Zhao's forces were destroyed. Thus ended the Han-Zhao dynasty; northern China would be dominated by the Later Zhao for the next 20 years.[136] Despite the Han-Zhao's defeat, the Chuge survived and remained a prominent ethnic group in northern China for the next two centuries.

Tiefu tribe and Helian Xia dynasty (309–431)

The chieftains of the Tiefu tribe were descendants of Qubei and were related to another tribe, the Dugu. Based on their name, which meant a person whose father was a Xiongnu and mother was a Xianbei, the Tiefu had mingled with the Xianbei, and records refer to them as "Wuhuan", which by the 4th-century had become a generic term for miscellaneous hu tribes with Donghu elements.[137] In 309, their chieftain, Liu Hu rebelled against the Western Jin in Shanxi but was driven out to Shuofang Commandery in the Ordos Loop. The Tiefu resided there for most of their existence, often as a vassal to their stronger neighbours before their power was destroyed by the Northern Wei dynasty in 392.

Liu Bobo, a surviving member of the Tiefu, went into exile and eventually offered his services to the Qiang-led Later Qin. He was assigned to guard Shuofang, but in 407, angered by Qin holding peace talks with the Northern Wei, he rebelled and founded a state known as the Helian Xia dynasty. Bobo strongly affirmed his Xiongnu lineage; his state name of "Xia" was based on the claim that the Xiongnu were descendants of the Xia dynasty, and he later changed his family name from "Liu" (劉) to the more Xiongnu-like "Helian" (赫連), believing it inappropriate to follow his matrilineal line from the Han. Helian Bobo placed the Later Qin in a perpetual state of warfare and greatly contributed to its decline. In 418, he conquered the Guanzhong region from the Eastern Jin dynasty after Jin destroyed Qin the previous year.

After Helian Bobo's death in 425, the Xia quickly declined due to pressure from the Northern Wei. In 428, the emperor, Helian Chang and capital were both captured by Wei forces. His brother, Helian Ding succeeded him and conquered the Western Qin in 431, but that same year, he was ambushed and imprisoned by the Tuyuhun while attempting a campaign against Northern Liang. The Xia was at its end, and the following year, Helian Ding was sent to Wei where he was executed.

Tongwancheng (meaning "Unite All Nations"), was one of the capitals of the Xia that was built during the reign of Helian Bobo. The ruined city was discovered in 1996[138] and the State Council designated it as a cultural relic under top state protection. The repair of the Yong'an Platform, where Helian Bobo reviewed parading troops, has been finished and restoration on the 31-meter-tall turret follows.[139][140]

Juqu clan and Northern Liang dynasty (401–460)

The Juqu clan were a Lushuihu family that founded the Northern Liang dynasty in modern-day Gansu in 397. Recent historiographies often classify the Northern Liang as a "Xiongnu" state, but there is still ongoing debate on the exact origin of the Lushuihu. A leading theory is that the Lushuihu were descendants of the Lesser Yuezhi that had intermingled with the Qiang people, but based on the fact that the Juqu's ancestors once served the Xiongnu empire, the Lushuihu could still be considered a branch of the Xiongnu. Regardless, contemporaneous records treat the Lushuihu as a distinct ethnic group.[141][142] The Northern Liang was known for its propagation of Buddhism in Gansu through their construction of Buddhist sites such as the Tiantishan and Mogao caves, and for being the last of the so-called Sixteen Kingdoms after it was conquered by the Northern Wei dynasty in 439.[143][144] There was also the Northern Liang of Gaochang, which existed between 442 and 460.

Significance

The Xiongnu confederation was unusually long-lived for a steppe empire. The purpose of raiding the Central Plain was not simply for goods, but to force the Central Plain polity to pay regular tribute. The power of the Xiongnu ruler was based on his control of Han tribute which he used to reward his supporters. The Han and Xiongnu empires rose at the same time because the Xiongnu state depended on Han tribute. A major Xiongnu weakness was the custom of lateral succession. If a dead ruler's son was not old enough to take command, power passed to the late ruler's brother. This worked in the first generation but could lead to civil war in the second generation. The first time this happened, in 60 BC, the weaker party adopted what Barfield calls the 'inner frontier strategy.' They moved south and submitted to the dominant Central Plain regime and then used the resources obtained from their overlord to defeat the Northern Xiongnu and re-establish the empire. The second time this happened, about 47 AD, the strategy failed. The southern ruler was unable to defeat the northern ruler and the Xiongnu remained divided.[145]

Ethnolinguistic origins

The Xiongnu empire is widely thought to have been multiethnic.[146] There are several theories on the ethnolinguistic identity of the Xiongnu, though there is no consensus among scholars as to what language was spoken by the Xiongnu elite.[147]

Proposed link to the Huns

| Pronunciation of 匈奴 | |

|---|---|

| Old Chinese (318 BCE): | *hoŋ-nâ |

| Eastern Han Chinese: | *hɨoŋ-nɑ |

| Middle Chinese: | *hɨoŋ-nuo |

| Modern Mandarin: | [ɕjʊ́ŋ nǔ] |

The Xiongnu-Hun hypothesis was originally proposed by the 18th-century French historian Joseph de Guignes, who noticed that ancient Chinese scholars had referred to members of tribes which were associated with the Xiongnu by names which were similar to the name "Hun", albeit with varying Chinese characters. Étienne de la Vaissière has shown that, in the Sogdian script used in the so-called "Sogdian Ancient Letters", both the Xiongnu and the Huns were referred to as the γwn (xwn), which indicates that the two names were synonymous.[17] Although the theory that the Xiongnu were the precursors of the Huns as they were later known in Europe is now accepted by many scholars, it has yet to become a consensus view. The identification with the Huns may either be incorrect or it may be an oversimplification (as would appear to be the case with a proto-Mongol people, the Rouran, who have sometimes been linked to the Avars of Central Europe).

Iranian theories

Most scholars agree that the Xiongnu elite may have been initially of Sogdian origin, while later switching to a Turkic language.[152] Harold Walter Bailey proposed an Iranian origin of the Xiongnu, recognizing all of the earliest Xiongnu names of the 2nd century BC as being of the Iranian type.[25] Central Asian scholar Christopher I. Beckwith notes that the Xiongnu name could be a cognate of Scythian, Saka and Sogdia, corresponding to a name for Eastern Iranian Scythians.[68][153] According to Beckwith the Xiongnu could have contained a leading Iranian component when they started out, but more likely they had earlier been subjects of an Iranian people and learned the Iranian nomadic model from them.[68]

In the 1994 UNESCO-published History of Civilizations of Central Asia, its editor János Harmatta claims that the royal tribes and kings of the Xiongnu bore Iranian names, that all Xiongnu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from a Scythian language, and that it is therefore clear that the majority of Xiongnu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language.[24]

According to a study by Alexander Savelyev and Choongwon Jeong, published in 2020 in the journal Evolutionary Human Sciences by Cambridge University Press, "The predominant part of the Xiongnu population is likely to have spoken Turkic". However, important cultural, technological and political elements may have been transmitted by Eastern Iranian-speaking Steppe nomads: "Arguably, these Iranian-speaking groups were assimilated over time by the predominant Turkic-speaking part of the Xiongnu population".[154]

Yeniseian theories

Lajos Ligeti was the first to suggest that the Xiongnu spoke a Yeniseian language. In the early 1960s Edwin Pulleyblank was the first to expand upon this idea with credible evidence. The Yeniseian theory proposes that the Jie, a western Xiongnu people, spoke a Yeniseian language. Hyun Jin Kim notes that the 7th AD Chinese conpendium, Jin Shu, contains a transliterated song of Jie origin, which appears to be Yeniseian. This song has led researchers Pulleyblank and Vovin to argue for a Yeniseian Jie dominant minority, that ruled over the other Xiongnu ethnicities, like Iranian and Turkic people. Kim has stated that the dominant Xiongnu language was likely Turkic or Yeniseian, but has cautioned that the Xiongnu were definitely a multi-ethnic society.[157]

Pulleybank and D. N. Keightley asserted that the Xiongnu titles "were originally Siberian words but were later borrowed by the Turkic and Mongolic peoples".[158] Titles such as tarqan, tegin and kaghan were also inherited from the Xiongnu language and are possibly of Yeniseian origin. For example, the Xiongnu word for "heaven" is theorized to come from Proto-Yeniseian *tɨŋVr.[159][160]

Vocabulary from Xiongnu inscriptions sometimes appears to have Yeniseian cognates which were used by Vovin to support his theory that the Xiongnu has a large Yeniseian component, examples of proposed cognates include words such as Xiongnu kʷala 'son' and Ket qalek 'younger son', Xiongnu sakdak 'boot' and Ket sagdi 'boot', Xiongnu gʷawa "prince" and Ket gij "prince", Xiongnu "attij" 'wife' and proto-Yeniseian "alrit", Ket "alit" and Xiongnu dar "north" compared to Yugh tɨr "north".[159][161] Pulleyblank also argued that because Xiongnu words appear to have clusters with r and l, in the beginning of the word it is unlikely to be of Turkic origin, and instead believed that most vocabulary we have mostly resemble Yeniseian languages.[162]

Alexander Vovin also wrote, that some names of horses in the Xiongnu language appear to be Turkic words with Yeniseian prefixes.[159]

An analysis by Savelyev and Jeong (2020) has cast doubt on the Yeniseian theory. If assuming that the ancient Yeniseians were represented by modern Ket people, who are more genetically similar to Samoyedic speakers, the Xiongnu do not display a genetic affinity for Yeniseian peoples.[154] A review by Wilson (2023) argues that the presence of Yeniseian-speakers among the multi-ethnic Xiongnu should not be rejected, and that "Yeniseian-speaking peoples must have played a more prominent (than heretofore recognized) role in the history of Eurasia during the first millennium of the Common Era".[163]

Turkic theories

According to a study by Alexander Savelyev and Choongwon Jeong, published in 2020 in the journal Evolutionary Human Sciences by Cambridge University Press, "The predominant part of the Xiongnu population is likely to have spoken Turkic". However, genetic studies found a mixture of haplogroups from western and eastern Eurasian origins that suggested a large genetic diversity within, and possibly multiple origins of Xiongnu elites. The Turkic-related component may be brought by eastern Eurasian genetic substratum.[154]

Other proponents of a Turkic language theory include E.H. Parker, Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, Julius Klaproth, Gustaf John Ramstedt, Annemarie von Gabain,[154] and Charles Hucker.[18] André Wink states that the Xiongnu probably spoke an early form of Turkic; even if Xiongnu were not "Turks" nor Turkic-speaking, they were in close contact with Turkic-speakers very early on.[166] Craig Benjamin sees the Xiongnu as either proto-Turks or proto-Mongols who possibly spoke a language related to the Dingling.[167]

Chinese sources link several Turkic peoples to the Xiongnu:

- According to the Book of Zhou, History of the Northern Dynasties, Tongdian, New Book of Tang, the Göktürks and the ruling Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation,[168][169][170][171][172]

- Uyghur Khagans claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to Chinese history Weishu, the founder of the Uyghur Khaganate was descended from a Xiongnu ruler).[176][177][178]

- Book of Wei states that the Yueban descended from remnants of the Northern Xiongnu chanyu's tribe and that Yueban's language and customs resembled Gaoche (高車),[179] another name of the Tiele.

- Book of Jin lists 19 southern Xiongnu tribes who entered Former Yan's borders, the 14th being the Alat (Ch. 賀賴 Helai ~ 賀蘭 Helan ~ 曷剌 Hela); Alat being glossed "piebald horse" (Ch. 駁馬 ~ 駮馬 Boma) in Old Turkic.[180][181][182]

However, Chinese sources also ascribe Xiongnu origins to the Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi and Khitans.[183]

Mongolic theories

Mongolian and other scholars have suggested that the Xiongnu spoke a language related to the Mongolic languages.[187][188] Mongolian archaeologists proposed that the Slab Grave Culture people were the ancestors of the Xiongnu, and some scholars have suggested that the Xiongnu may have been the ancestors of the Mongols.[27] Nikita Bichurin considered Xiongnu and Xianbei to be two subgroups (or dynasties) of but one same ethnicity.[189]

According to the "Book of Song", the Rourans, whom Book of Wei identified as offspring of Proto-Mongolic[190] Donghu people,[191] possessed the alternative name(s) 大檀 Dàtán "Tatar" and/or 檀檀 Tántán "Tartar" and according to Book of Liang, "they also constituted a separate branch of the Xiongnu".[192][193] Old Book of Tang mentioned twenty Shiwei tribes,[194] whom other Chinese sources (Book of Sui, New Book of Tang) associated with the Khitans,[195] another people who in turn descended from the Xianbei[196] and were also associated with the Xiongnu.[197] While the Xianbei, Khitans, and Shiwei are generally believed to be predominantly Mongolic- and Para-Mongolic-speaking,[195][198][199] yet Xianbei were stated to descend from the Donghu, whom Sima Qian distinguished from the Xiongnu.[200][201][202] (notwithstanding Sima Qian's inconsistency[59][60][61][55]). Additionally, Chinese chroniclers routinely ascribed Xiongnu origins to various nomadic groups: for examples, Xiongnu ancestry was ascribed to Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi as well as Turkic-speaking Göktürks and Tiele;[183]

Genghis Khan refers to the time of Modu Chanyu as "the remote times of our Chanyu" in his letter to Daoist Qiu Chuji.[203] Sun and moon symbol of Xiongnu that discovered by archaeologists is similar to Mongolian Soyombo symbol.[204][205][206]

Multiple ethnicities

Since the early 19th century, a number of Western scholars have proposed a connection between various language families or subfamilies and the language or languages of the Xiongnu. Albert Terrien de Lacouperie considered them to be multi-component groups.[32] Many scholars believe the Xiongnu confederation was a mixture of different ethno-linguistic groups, and that their main language (as represented in the Chinese sources) and its relationships have not yet been satisfactorily determined.[208] Kim rejects "old racial theories or even ethnic affiliations" in favour of the "historical reality of these extensive, multiethnic, polyglot steppe empires".[209]

Chinese sources link the Tiele people and Ashina to the Xiongnu, not all Turkic peoples. According to the Book of Zhou and the History of the Northern Dynasties, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation,[210][211] but this connection is disputed,[212] and according to the Book of Sui and the Tongdian, they were "mixed nomads" (traditional Chinese: 雜胡; simplified Chinese: 杂胡; pinyin: zá hú) from Pingliang.[213][214] The Ashina and Tiele may have been separate ethnic groups who mixed with the Xiongnu.[215] Indeed, Chinese sources link many nomadic peoples (hu; see Wu Hu) on their northern borders to the Xiongnu, just as Greco-Roman historiographers called Avars and Huns "Scythians". The Greek cognate of Tourkia (Greek: Τουρκία) was used by the Byzantine emperor and scholar Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in his book De Administrando Imperio,[216][217] though in his use, "Turks" always referred to Magyars.[218] Such archaizing was a common literary topos, and implied similar geographic origins and nomadic lifestyle but not direct filiation.[219]

Some Uyghurs claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to Chinese history Weishu, the founder of the Uyghur Khaganate was descended from a Xiongnu ruler),[176] but many contemporary scholars do not consider the modern Uyghurs to be of direct linear descent from the old Uyghur Khaganate because modern Uyghur language and Old Uyghur languages are different.[220] Rather, they consider them to be descendants of a number of people, one of them the ancient Uyghurs.[221][222][223]

In various kinds of ancient inscriptions on monuments of Munmu of Silla, it is recorded that King Munmu had Xiongnu ancestry. According to several historians, it is possible that there were tribes of Koreanic origin. There are also some Korean researchers that point out that the grave goods of Silla and of the eastern Xiongnu are alike.[224][225][226][227][228]

Language isolate theories

Turkologist Gerhard Doerfer has denied any possibility of a relationship between the Xiongnu language and any other known language, even any connection with Turkic or Mongolian.[158]

Geographic origins

The original geographic location of the Xiongnu is disputed among steppe archaeologists. Since the 1960s, the geographic origin of the Xiongnu has attempted to be traced through an analysis of Early Iron Age burial constructions. No region has been proven to have mortuary practices that clearly match those of the Xiongnu.[229]

Archaeology

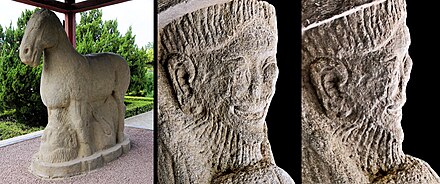

In the 1920s, Pyotr Kozlov oversaw the excavation of royal tombs at the Noin-Ula burial site in northern Mongolia, dated to around the first century CE. Other Xiongnu sites have been unearthed in Inner Mongolia, such as the Ordos culture. Sinologist Otto Maenchen-Helfen has said that depictions of the Xiongnu of Transbaikalia and the Ordos commonly show individuals with West Eurasian features.[230] Iaroslav Lebedynsky said that West Eurasian depictions in the Ordos region should be attributed to a "Scythian affinity".[231]

Portraits found in the Noin-Ula excavations demonstrate other cultural evidences and influences, showing that Chinese and Xiongnu art have influenced each other mutually. Some of these embroidered portraits in the Noin-Ula kurgans also depict the Xiongnu with long braided hair with wide ribbons, which is seen to be identical with the Ashina clan hair-style.[232] Well-preserved bodies in Xiongnu and pre-Xiongnu tombs in the Mongolian Republic and southern Siberia show both East Asian and West Eurasian features.[233]

Analysis of cranial remains from some sites attributed to the Xiongnu have revealed that they had dolichocephalic skulls with East Asian craniometrical features, setting them apart from neighboring populations in present-day Mongolia.[234] Russian and Chinese anthropological and craniofacial studies show that the Xiongnu were physically very heterogenous, with six different population clusters showing different degrees of West Eurasian and East Asian physical traits.[27]

Presently, there exist four fully excavated and well documented cemeteries: Ivolga,[236] Dyrestui,[237] Burkhan Tolgoi,[238][239] and Daodunzi.[240][241] Additionally thousands of tombs have been recorded in Transbaikalia and Mongolia.

The archaeologists have chosen to, for the most part, refrain from positing anything about Han-Xiongnu relations based on the material excavated. However, they were willing to mention the following:

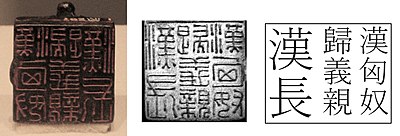

"There is no clear indication of the ethnicity of this tomb occupant, but in a similar brick-chambered tomb of the late Eastern Han period at the same cemetery, archaeologists discovered a bronze seal with the official title that the Han government bestowed upon the leader of the Xiongnu. The excavators suggested that these brick chamber tombs all belong to the Xiongnu (Qinghai 1993)."[242]

Classifications of these burial sites make distinction between two prevailing type of burials: "(1) monumental ramped terrace tombs which are often flanked by smaller "satellite" burials and (2) 'circular' or 'ring' burials."[243] Some scholars consider this a division between "elite" graves and "commoner" graves. Other scholars, find this division too simplistic and not evocative of a true distinction because it shows "ignorance of the nature of the mortuary investments and typically luxuriant burial assemblages [and does not account for] the discovery of other lesser interments that do not qualify as either of these types."[244]

Genetics

Maternal lineages

A 2003 study found that 89% of Xiongnu maternal lineages are of East Asian origin, while 11% were of West Eurasian origin. However, a 2016 study found that 37.5% of Xiongnu maternal lineages were West Eurasian, in a central Mongolian sample.[245]

According to Rogers & Kaestle (2022), these studies make clear that the Xiongnu population is extremely similar to the preceding Slab Grave population, which had a similar frequency of Eastern and Western maternal haplogroups, supporting a hypothesis of continuity from the Slab Grave period to the Xiongnu. They wrote that the bulk of the genetics research indicates that roughly 27% of Xiongnu maternal haplogroups were of West Eurasian origin, while the rest were East Asian.[246]

Some examples of maternal haplogroups observed in Xiongnu specimens include D4b2b4, N9a2a, G3a3, D4a6 and D4b2b2b.[247] and U2e1.[248]

Paternal lineages

According to Rogers & Kaestle (2022), roughly 47% of Xiongnu period remains belonged to paternal haplogroups associated with modern West Eurasians, while the rest (53%) belonged to East Asian haplogroups. They observed that this contrasts strongly with the preceding Slab Grave period, which was dominated by East Asian patrilineages. They suggest that this may reflect an aggressive expansion of people with West Eurasian paternal haplogroups, or perhaps the practice of marriage alliances or cultural networks favoring people with Western patrilines.[249]

Some examples of paternal haplogroups in Xiongnu specimens include Q1b,[250][251] C3,[252] R1, R1b, O3a and O3a3b2,[253] R1a1a1b2a-Z94, R1a1a1b2a2-Z2124, Q1a, N1a,[254] J2a, J1a and E1b1b1a.[255]

According to Lee & Kuang, the main paternal lineages of 62 Xiongnu Elite remains in the Egiin Gol valley belonged to the paternal haplogroups N1c1, Q-M242, and C-M217. One sample from Duurlig Nars belonged to R1a1 and another to C-M217. Xiongnu remains from Barkol belonged exclusively to haplogroup Q. They argue that the haplogroups C2, Q and N likely formed the major paternal haplogroups of the Xiongnu tribes, while R1a was the most common paternal haplogroup (44.5%) among neighbouring nomads from the Altai mountain, who were probably incorporated into the Xiongnu confederation and may be associated with the Jie people.[256]

Autosomal ancestry

A study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in October 2006 detected significant genetic continuity between the examined individuals at Egyin Gol and modern Mongolians.[257]

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of five Xiongnu.[258] The study concluded that Xiongnu confederation was genetically heterogeneous, and Xiongnu individuals belonging to two distinct groups, one being of primarily East Asian origin (associated with the earlier Slab-grave culture) and the other presenting considerable admixture levels with West Eurasian (possibly from Central Saka) sources. The evidence suggested that the Huns probably emerged through minor male-driven geneflow into the Saka through westward migrations of the Xiongnu.[259]

A study published in November 2020 examined 60 early and late Xiongnu individuals from across of Mongolia. The study found that the Xiongnu resulted from the admixture of three different clusters from the Mongolian region. The two early genetic clusters are "early Xiongnu_west" from the Altai Mountains (formed at 92% by the hybrid Eurasian Chandman ancestry, and 8% BMAC ancestry), and "early Xiongnu_rest" from the Mongolian Plateau (individuals with primarily Ulaanzuukh-Slab Grave ancestry, or mixed with "early Xiongnu_west"). The later third cluster named "late Xiongnu" has even higher heterogenity, with the continued combination of Chandman and Ulaanzuukh-Slab Grave ancestry, and additional geneflow from Sarmatian and Han Chinese sources. Their uniparental haplogroup assignments also showed heterogenetic influence on their ethnogenesis as well as their connection with Huns.[207][260] In contrast, the later Mongols had a much higher eastern Eurasian ancestry as a whole, similar to that of modern-day Mongolic-speaking populations.[261]

A Xiongnu remain (GD1-4) analysed in a 2024 study was found to be entirely derived from Ancient Northeast Asians without any West Eurasian-associated ancestry. The sample clustered closely with a Göktürk remain (GD1-1) from the later Turkic period.[262]

Relationship between ethnicity and status among the Xiongnu

Although the Xiongnu were ethnically heterogeneous as a whole, it appears that variability was highly related to social status. Genetic heterogeneity was highest among retainers of low status, as identified by their smaller and peripheral tombs. These retainers mainly displayed ancestry related to the Chandman/Uyuk culture (characterized by a hybrid Eurasian gene pool combining the genetic profile of the Sintashta culture and Baikal hunter-gatherers (Baikal EBA)), or various combinations of Chandman/Uyuk and Ancient Northeast Asian Ulaanzuukh/Slab Grave profiles.[146]

On the contrary, high status Xiongnu individuals tended to have less genetic diversity, and their ancestry was essentially derived from the Eastern Eurasian Ulaanzuukh/Slab Grave culture, or alternatively from the Xianbei, suggesting multiple sources for their Eastern ancestry. High Eastern ancestry was more common among high status female samples, while low status male samples tended to be more diverse and having higher Western ancestry.[146] A likely chanyu, a male ruler of the Empire identified by his prestigious tomb, was shown to have had similar ancestry as a high status female in the "western frontiers", deriving about 39.3% Slab Grave (or Ancient Northeast Asian) genetic ancestry, 51.9% Han (or Yellow River farmers) ancestry, with the rest (8.8%) being Saka (Chandman) ancestry.[146]

Culture

Art

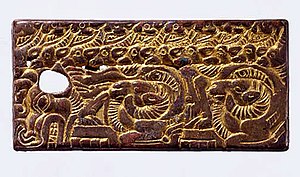

Within the Xiongnu culture more variety is visible from site to site than from "era" to "era," in terms of the Chinese chronology, yet all form a whole that is distinct from that of the Han and other peoples of the non-Chinese north.[268] In some instances, the iconography cannot be used as the main cultural identifier, because art depicting animal predation is common among the steppe peoples. An example of animal predation associated with Xiongnu culture is that of a tiger carrying dead prey.[268] A similar motif appears in work from Maoqinggou, a site which is presumed to have been under Xiongnu political control but is still clearly non-Xiongnu. In the Maoqinggou example, the prey is replaced with an extension of the tiger's foot. The work also depicts a cruder level of execution; Maoqinggou work was executed in a rounder, less detailed style.[268] In its broadest sense, Xiongnu iconography of animal predation includes examples such as the gold headdress from Aluchaideng and gold earrings with a turquoise and jade inlay discovered in Xigoupan, Inner Mongolia.[268]

Xiongnu art is harder to distinguish from Saka or Scythian art. There is a similarity present in stylistic execution, but Xiongnu art and Saka art often differ in terms of iconography. Saka art does not appear to have included predation scenes, especially with dead prey, or same-animal combat. Additionally, Saka art included elements not common to Xiongnu iconography, such as winged, horned horses.[268] The two cultures also used two different kinds of bird heads. Xiongnu depictions of birds tend to have a medium-sized eye and beak, and they are also depicted with ears, while Saka birds have a pronounced eye and beak, and no ears.[269] Some scholars[who?] claim these differences are indicative of cultural differences. Scholar Sophia-Karin Psarras suggests that Xiongnu images of animal predation, specifically tiger-and-prey, are spiritual, representative of death and rebirth, and that same-animal combat is representative of the acquisition or maintenance of power.[269]

Rock art and writing

The rock art of the Yin and Helan Mountains is dated from the 9th millennium BC to the 19th century AD. It consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and only minimally of painted images.[271]

Chinese sources indicate that the Xiongnu did not have an ideographic form of writing like Chinese, but in the 2nd century BC, a renegade Chinese dignitary Yue "taught the Shanyu to write official letters to the Chinese court on a wooden tablet 31 cm long, and to use a seal and large-sized folder." The same sources tell that when the Xiongnu noted down something or transmitted a message, they made cuts on a piece of wood ('ke-mu'), and they also mention a "Hu script" (vol. 110). At Noin-Ula and other Xiongnu burial sites in Mongolia and the region north of Lake Baikal, among the objects discovered during excavations conducted between 1924 and 1925 were over 20 carved characters. Most of these characters are either identical or very similar to letters of the Old Turkic alphabet of the Early Middle Ages found on the Eurasian steppes. From this, some specialists conclude that the Xiongnu used a script similar to the ancient Eurasian runiform, and that this alphabet was a basis for later Turkic writing.[272]

Religion and diet

According to the Book of Han, "the Xiongnu called Heaven (天) 'Chēnglí,' (撐犁) [273] a Chinese transcription of Tengri. The Xiongnu were a nomadic people. From their lifestyle of herding flocks and their horse-trade with China, it can be concluded that their diet consist mainly of mutton, horse meat and wild geese that were shot down. Historical evidence gives reason to believe that, from the 2nd century BC, proto-Mongol peoples (the Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Khitans) were familiar with Buddhism. On the territory of the Ivolginsk Settlement, remains of Buddhist prayer beads were found in a Xiongnu grave.[274]

See also

- List of Xiongnu rulers (Chanyus)

- Rulers family tree

- Nomadic empire

- Ethnic groups in Chinese history

- History of the Han dynasty

- Ban Yong

- Zubu

- List of largest empires

- Ordos culture

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (16 March 2015). Global Connections: Volume 1, To 1500: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-316-29777-3.

- ^ Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- ^ Fauve, Jeroen (2021). The European Handbook of Central Asian Studies. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-8382-1518-1.

- ^ Hartley, Charles W.; Yazicioğlu, G. Bike; Smith, Adam T. (19 November 2012). The Archaeology of Power and Politics in Eurasia: Regimes and Revolutions. Cambridge University Press. p. 245, Fig 12.3. ISBN 978-1-139-78938-7.

- ^ a b Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC – AD 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ^ Shufen, Liu (2002). "Ethnicity and the Suppression of Buddhism in Fifth-century North China: The Background and Significance of the Gaiwu Rebellion". Asia Major. 15 (1): 1–21. ISSN 0004-4482. JSTOR 41649858.

- ^ a b Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). 匈 – 上古音系第一三千八百九十字 [匈 - The 13890th word of the Ancient Phonological System]. ytenx.org [韻典網] (in Chinese). Rearranged by BYVoid.

- ^ a b Zheng Zhang (Chinese: 鄭張), Shang-fang (Chinese: 尚芳). 奴 – 上古音系第九千六百字 [奴 – The 9600th word of the Ancient Phonological System]. ytenx.org [韻典網] (in Chinese). Rearranged by BYVoid.

- ^ Gökalp, Ziya (2020). Türk Medeniyeti Tarihi. ISBN 978-605-4369-46-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Xiongnu People". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2020-03-11. Retrieved 2015-07-25.

- ^ Di Cosmo 2004, p. 186.

- ^ Chase-Dunn, C.; Anderson, E. (18 February 2005). The Historical Evolution of World-Systems. Springer. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-4039-8052-6. "The primary focus of the new threat became the Xiongnu who emerged rather abruptly in the late 4th century B.C. initially subordinated to the Yuezhi, the Xiongnu overthrew the nomadic hierarchy while also escalating its attacks on Chinese areas."

- ^ a b Grousset 1970, pp. 19, 26–27.

- ^ Pulleyblank 2000, p. 17.

- ^ a b Schuessler 2014, pp. 257, 264.

- ^ a b Beckwith 2009, pp. 404–405, notes 51–52.

- ^ a b Étienne de la Vaissière (15 November 2006). "Xiongnu". Encyclopedia Iranica online. Archived from the original on 2012-01-04.

- ^ a b Hucker 1975, p. 136.

- ^ Savelyev, Alexander; Jeong, Choongwon (10 May 2020). "Early nomads of the Eastern Steppe and their tentative connections in the West". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.18. hdl:21.11116/0000-0007-772B-4. PMC 7612788. PMID 35663512. S2CID 218935871.

The predominant part of the Xiongnu population is likely to have spoken Turkic (Late Proto-Turkic, to be more precise)

- ^ Robbeets, Martine; Bouckaert, Remco (1 July 2018). "Bayesian phylolinguistics reveals the internal structure of the Transeurasian family". Journal of Language Evolution. 3 (2): 145–162. doi:10.1093/jole/lzy007. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-E3E6-B. ISSN 2058-4571.

- ^ Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt (2019), "Northern Dynasties and Southern Dynasties", Chinese Architecture, Princeton University Press, pp. 72–103, doi:10.2307/j.ctvc77f7s.11, S2CID 243720017"Turcs ou Turks". Larousse Rncyclopedie (in French). Larousse Éditions. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ Book of Zhou, vol. 50.Henning 1948.

- ^ Sims-Williams 2004.Pritsak 1959.Hucker 1975, p. 136.Jinshu vol. 97 Four Barbarians - Xiongnu".Weishu. Vol. 102: Wusun, Shule, & Yueban.

悅般國,…… 其先,匈奴北單于之部落也。…… 其風俗言語與高車同

Yuanhe Maps and Records of Prefectures and Counties vol. 4 quote: "北人呼駮馬為賀蘭.Kim, Hyun Jin (18 April 2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511920493. ISBN 978-0-511-92049-3.Du You. Tongdian. Vol. 200: 突厥謂駮馬為曷剌,亦名曷剌國。.Wink 2002, pp. 60–61. - ^ a b Harmatta 1994, p. 488: "Their royal tribes and kings (shan-yü) bore Iranian names and all the Hsiung-nu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from an Iranian language of Saka type. It is therefore clear that the majority of Hsiung-nu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language."

- ^ a b Bailey 1985, pp. 21–45.

- ^ Jankowski 2006, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c Tumen D (February 2011). "Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia" (PDF). Oriental Studies. 49. Dankook University Institute of Oriental Studies: 25, 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-29.

- ^ Di Cosmo 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Adas 2001, p. 88.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2000). "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal. 44 (1): 87–104. JSTOR 41928223.

- ^ 高晶一, Jingyi Gao (2017). "Quèdìng xià guó jí kǎitè rén de yǔyán wéi shǔyú hànyǔ zú hé yè ní sāi yǔxì gòngtóng cí yuán" 確定夏國及凱特人的語言為屬於漢語族和葉尼塞語系共同詞源 [Xia and Ket Identified by Sinitic and Yeniseian Shared Etymologies]. Central Asiatic Journal. 60 (1–2): 51–58. doi:10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051. S2CID 165893686.

- ^ a b Geng 2005.

- ^ Gao, Jingyi (高晶一) (2013). "Huns and Xiongnu Identified by Hungarian and Yeniseian Shared Etymologies" (PDF). Central Asiatic Journal. 56: 41. ISSN 0008-9192. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.56.2013.0041.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. (2015). "The Kai, the Khongai, and the Names of the Xiōngnú". International Journal of Eurasian Studies. 2: p of 45–47 of 35–63.

- ^ Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Rohland, Nadin; Bernardos, Rebecca (6 September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457). doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- ^ Khenzykhenova, Fedora I.; Kradin, Nikolai N.; Danukalova, Guzel A.; Shchetnikov, Alexander A.; Osipova, Eugenia M.; Matveev, Arkady N.; Yuriev, Anatoly L.; Namzalova, Oyuna D. -Ts; Prokopets, Stanislav D.; Lyashchevskaya, Marina A.; Schepina, Natalia A.; Namsaraeva, Solonga B.; Martynovich, Nikolai V. (30 April 2020). "The human environment of the Xiongnu Ivolga Fortress (West Trans-Baikal area, Russia): Initial data". Quaternary International. 546: 216–228. Bibcode:2020QuInt.546..216K. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2019.09.041. ISSN 1040-6182. S2CID 210787385. "The slab graves culture existed in this territory prior to the Xiongnu empire. Sites of this culture dating back to approximately 1100-400/300 BC are common in Mongolia and the Trans-Baikal area. The earliest calibrated dates are prior to 1500 BC (Miyamoto et al., 2016). Later dates are usually 100–200 years earlier than the Xiongnu culture. Therefore, it is customarily considered that the slab grave culture preceded the Xiongnu culture. There is only one case, reported by Miyamoto et al. (2016), in which the date of the slab grave corresponds to the time of the making of the Xiongnu Empire."

- ^ Rogers & Kaestle 2022

- ^ a b c d Tse, Wicky W. K. (27 June 2018). The Collapse of China's Later Han Dynasty, 25-220 CE: The Northwest Borderlands and the Edge of Empire. Routledge. pp. 45–46, 63 note 40. ISBN 978-1-315-53231-8.

- ^ Linduff, Katheryn M.; Rubinson, Karen S. (2021). Pazyryk Culture Up in the Altai. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-429-85153-7.

The rise of the confederation of the Xiongnu, in addition, clearly affected this region as it did most regions of the Altai

- ^ "Pazyryk | archaeological site, Kazakhstan". Britannica.com. 11 September 2001. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ^ State Hermitage Museum 2007

- ^ Whitehouse 2016, p. 369: "From that time until the HAN dynasty the Ordos steppe was the home of semi-nomadic Indo-European peoples whose culture can be regarded as an eastern province of a vast Eurasian continuum of Scytho-Siberian cultures."

- ^ Harmatta 1992, p. 348: "From the first millennium b.c., we have abundant historical, archaeological and linguistic sources for the location of the territory inhabited by the Iranian peoples. In this period the territory of the northern Iranians, they being equestrian nomads, extended over the whole zone of the steppes and the wooded steppes and even the semi-deserts from the Great Hungarian Plain to the Ordos in northern China."

- ^ Unterländer, Martina; Palstra, Friso; Lazaridis, Iosif; Pilipenko, Aleksandr; Hofmanová, Zuzana; Groß, Melanie; Sell, Christian; Blöcher, Jens; Kirsanow, Karola; Rohland, Nadin; Rieger, Benjamin (3 March 2017). "Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe". Nature Communications. 8: 14615. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814615U. doi:10.1038/ncomms14615. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5337992. PMID 28256537.

- ^ Benjamin, Craig (29 March 2017). "The Yuezhi". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.49. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7.

- ^ Bang, Peter Fibiger; Bayly, C. A.; Scheidel, Walter (2 December 2020). The Oxford World History of Empire: Volume Two: The History of Empires. Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-19-753278-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Marshak, Boris Ilʹich (1 January 2002). Peerless Images: Persian Painting and Its Sources. Yale University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-300-09038-3.

- ^ Ilyasov, Jangar Ya.; Rusanov, Dmitriy V. (1997). "A Study on the Bone Plates from Orlat". Silk Road Art and Archaeology. 5 (1997/98). Kamakura, Japan: The Institute of Silk Road Studies: 107–159. ISSN 0917-1614. p. 127:

The image on this belt-buckle represents a rider striking a wild boar with a spear.

- ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)" [On some vestiges and new indications of Hellenism in the arts between Bactria and Gandhāra (130 BC-100 AD approximately)]. Journal des Savants: 35–39.