Legal status of same-sex marriage

| Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties: | |

Prison; death not enforced | |

Death under militias | Prison, with arrests or detention |

Prison, not enforced1 | |

| Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions: | |

Extraterritorial marriage2 | |

Limited foreign | Optional certification |

None | Restrictions of expression, not enforced |

Restrictions of association with arrests or detention | |

1No imprisonment in the past three years or moratorium on law.

2Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships.

The legal status of same-sex marriage has changed in recent years in numerous jurisdictions around the world. The current trends and consensus of political authorities and religions throughout the world are summarized in this article.

Civil recognition

[edit]Global summary

[edit]Same-sex marriage is legal in the following countries:

| # | Country | Legalization method | Date of nationwide legalization | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Passed by the States General[a] | 1 April 2001 | Legalized in the special municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba in 2012, and the constituent countries of Aruba and Curaçao in 2024. Remains unrecognized in Sint Maarten. | |

| 2 | Passed by the Belgian Federal Parliament | 1 June 2003 | ||

| 3 | Passed by the Cortes Generales | 3 July 2005 | ||

| 4 | Passed by the Parliament of Canada | 20 July 2005 | Legal in some provinces and territories since 2003. | |

| 5 | Passed by the Parliament of South Africa | 30 November 2006 | ||

| 6 | Passed by the Storting | 1 January 2009 | ||

| 7 | Passed by the Riksdag | 1 May 2009 | ||

| 8 | Passed by the Assembly of the Republic | 5 June 2010 | ||

| 9 | Passed by the Althing | 27 June 2010 | ||

| 10 | Passed by the Congress of the Argentine Nation | 22 July 2010 | ||

| 11 | Passed by the Folketing | 15 June 2012 | Legalized in the constituent countries of Greenland in 2016 and Faroe Islands in 2017. | |

| 12 | Ruling of the National Justice Council | 16 May 2013 | Legal in some states since 2011. | |

| 13 | Passed by the French Parliament | 18 May 2013 | ||

| 14 | Passed by the General Assembly of Uruguay | 5 August 2013 | ||

| 15 | Passed by the New Zealand House of Representatives | 19 August 2013 | Excluding the territory of Tokelau. Not legal in associated states of Niue and the Cook Islands. | |

| 16 | Passed by the Chamber of Deputies | 1 January 2015 | ||

| 17 | Ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States[b] | 26 June 2015 | Legal in some states since 2004. Not legal in some sovereign reservations and recognized but not performed in American Samoa. | |

| 18 | Approved by referendum and passed by the Oireachtas | 16 November 2015 | ||

| 19 | Ruling of the Constitutional Court of Colombia | 28 April 2016 | ||

| 20 | Passed by the Eduskunta | 1 March 2017 | ||

| 21 | Passed by the Parliament of Malta | 1 September 2017 | ||

| 22 | Passed by the Bundestag and the Bundesrat | 1 October 2017 | ||

| 23 | Supported in survey and passed by the Parliament of Australia | 9 December 2017 | ||

| 24 | Ruling of the Constitutional Court of Austria | 1 January 2019 | ||

| 25 | Passed by the Legislative Yuan after ruling of the Constitutional Court of Taiwan | 24 May 2019 | ||

| 26 | Ruling of the Constitutional Court of Ecuador | 8 July 2019 | ||

| 27 | Passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the Scottish Parliament | 13 January 2020 | Legal in England, Wales and Scotland since 2014. Legal in Northern Ireland since 2020. Legal in most British Overseas Territories except in the Caribbean territories. | |

| 28 | Ruling of the Supreme Court of Costa Rica | 26 May 2020 | ||

| 29 | Passed by the National Congress of Chile | 10 March 2022 | ||

| 30 | Passed by the Federal Assembly of Switzerland and adopted in a referendum | 1 July 2022 | ||

| 31 | Ruling of the Constitutional Court of Slovenia[c] | 9 July 2022 | ||

| 32 | Passed by the National Assembly of People's Power and adopted in a referendum | 27 September 2022 | ||

| 33 | A combination of executive decrees, legislative measures, and judicial rulings | 31 December 2022 | Legal in Mexico City since 2010 and some states since 2012. | |

| 34 | Passed by the General Council | 17 February 2023 | ||

| 35 | Passed by the Riigikogu | 1 January 2024 | ||

| 36 | Passed by the Hellenic Parliament | 16 February 2024 | ||

| - | Passed by the Landtag | 1 January 2025 | ||

| - | Passed by the National Assembly of Thailand | 22 January 2025 |

Opinion polls

[edit]- Opinion polls for same-sex marriage by country

| Country | Pollster | Year | For[d] | Against[d] | Neither[e] | Margin of error | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% | 73% (74%) | 1% | [1] | ||

| Institut d'Estudis Andorrans | 2013 | 70% (79%) | 19% (21%) | 11% | [2] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | – | – | [3] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (81%) | 16% [9% support some rights] (19%) | 15% not sure | ±5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 67% (72%) | 26% (28%) | 7% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 3% (3%) | 96% (97%) | 1% | ±3% | [6] [7] | |

| 2021 | 46% | [8] | |||||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 64% (73%) | 25% [13% support some rights] (28%) | 12% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 75% (77%) | 23% | 2% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 65% (68%) | 30% (32%) | 5% | [9] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2015 | 11% | – | – | [10] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 16% (16%) | 81% (84%) | 3% | ±4% | [6] [7] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (78%) | 19% [9% support some rights] (22%) | 12% not sure | ±5% | [4] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% | 19% | 2% not sure | [9] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 8% | – | – | [10] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 35% | 65% | – | ±1.0% | [3] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% (27%) | 71% (73%) | 3% | [1] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 51% (62%) | 31% [17% support some rights] (38%) | 18% not sure | ±3.5% [f] | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 52% (57%) | 40% (43%) | 8% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 17% (18%) | 75% (82%) | 8% | [9] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 57% (58%) | 42% | 1% | [5] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 65% (75%) | 22% [10% support some rights] (25%) | 13% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 79% (84%) | 15% (16%) | 6% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Cadem | 2024 | 77% (82%) | 22% (18%) | 2% | ±3.6% | [11] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 43% (52%) | 39% [20% support some rights] (48%) | 18% not sure | ±3.5% [f] | [12] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 46% (58%) | 33% [19% support some rights] (42%) | 21% | ±5% [f] | [4] | |

| CIEP | 2018 | 35% | 64% | 1% | [13] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) | 51% (55%) | 7% | [9] | ||

| Apretaste | 2019 | 63% | 37% | – | [14] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% (53%) | 44% (47%) | 6% | [9] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 60% | 34% | 6% | [9] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 93% | 5 | 2% | [9] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 10% | 90% | – | ±1.1% | [3] | |

| CDN 37 | 2018 | 45% | 55% | - | [15] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2019 | 23% (31%) | 51% (69%) | 26% | [16] | ||

| Universidad Francisco Gavidia | 2021 | 82.5% | – | [17] | |||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 41% (45%) | 51% (55%) | 8% | [9] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 76% (81%) | 18% (19%) | 6% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 62% (70%) | 26% [16% support some rights] (30%) | 12% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 82% (85%) | 14% (15%) | 4% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% (85%) | 14 (%) (15%) | 7% | [9] | ||

| Women's Initiatives Supporting Group | 2021 | 10% (12%) | 75% (88%) | 15% | [18] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (83%) | 18% [10% support some rights] (20%) | 12% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 80% (82%) | 18% | 2% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% (87%) | 13%< | 3% | [9] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 48% (49%) | 49% (51%) | 3% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 57% (59%) | 40% (41%) | 3% | [9] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | 88% | – | ±1.4%c | [3] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 23% | 77% | – | ±1.1% | [3] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 21% | 79% | – | ±1.3% | [10] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 5% | 95% | – | ±0.3% | [3] | |

| CID Gallup | 2018 | 17% (18%) | 75% (82%) | 8% | [19] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 58% (59%) | 40% (41%) | 2% | [5] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 44% (56%) | 35% [18% support some rights] (44%) | 21% not sure | ±5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 31% (33%) | 64% (67%) | 5% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) | 52% (55%) | 6% | [9] | ||

| Gallup | 2006 | 89% | 11% | – | [20] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 53% (55%) | 43% (45%) | 4% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 5% | 92% (95%) | 3% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 68% (76%) | 21% [8% support some rights] (23%) | 10% | ±5%[f] | [4] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 86% (91%) | 9% | 5% | [9] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 36% (39%) | 56% (61%) | 8% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 58% (66%) | 29% [19% support some rights] (33%) | 12% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 73% (75%) | 25% | 2% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 69% (72%) | 27% (28%) | 4% | [9] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 16% | 84% | – | ±1.0% | [3] | |

| Kyodo News | 2023 | 64% (72%) | 25% (28%) | 11% | [21] | ||

| Asahi Shimbun | 2023 | 72% (80%) | 18% (20%) | 10% | [22] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 42% (54%) | 31% [25% support some rights] (40%) | 22% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 68% (72%) | 26% (28%) | 6% | ±2.75% | [5] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2016 | 7% (7%) | 89% (93%) | 4% | [6] [7] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 9% | 90% (91%) | 1% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) | 77% (79%) | 3% | [1] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 36% | 59% | 5% | [9] | ||

| Liechtenstein Institut | 2021 | 72% | 28% | 0% | [23] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 39% | 55% | 6% | [9] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% | 13% | 3% | [9] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 17% | 82% (83%) | 1% | [5] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 74% | 24% | 2% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 55% | 29% [16% support some rights] | 17% not sure | ±3.5%[f] | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (66%) | 32% (34%) | 5% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Europa Libera Moldova | 2022 | 14% | 86% | [24] | |||

| IPSOS | 2023 | 36% (37%) | 61% (63%) | 3% | [1] | ||

| Lambda | 2017 | 28% (32%) | 60% (68%) | 12% | [25] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 77% | 15% [8% support some rights] | 8% not sure | ±5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 89% (90%) | 10% | 1% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 2% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 70% (78%) | 20% [11% support some rights] (22%) | 9% | ±3.5% | [26] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 25% | 75% | – | ±1.0% | [3] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 2% | 97% (98%) | 1% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) | 78% (80%) | 2% | [1] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 72% (79%) | 19% (21%) | 9% | [6] [7] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 22% | 78% | – | ±1.1% | [3] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 26% | 74% | – | ±0.9% | [3] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 36% | 44% [30% support some rights] | 20% | ±5% [f] | [4] | |

| SWS | 2018 | 22% (26%) | 61% (73%) | 16% | [27] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (54%) | 43% (46%) | 6% | [28] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (43%) | 54% (57%) | 5% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| United Surveys by IBRiS | 2024 | 50% (55%) | 41% (45%) | 9% | [29] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% | 45% | 5% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 80% (84%) | 15% [11% support some rights] (16%) | 5% | [26] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 81% | 14% | 5% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 25% (30%) | 59% [26% support some rights] (70%) | 17% | ±3.5% | [26] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 25% | 69% | 6% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 17% (21%) | 64% [12% support some rights] (79%) | 20% not sure | ±4.8% [f] | [12] | |

| FOM | 2019 | 7% (8%) | 85% (92%) | 8% | ±3.6% | [30] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 9% | 91% | – | ±1.0% | [3] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 11% | 89% | – | ±0.9% | [3] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 4% | 96% | – | ±0.6% | [3] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 24% (25%) | 73% (75%) | 3% | [1] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 33% | 46% [21% support some rights] | 21% | ±5% [f] | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (47%) | 51% (53%) | 4% | [5] | ||

| Focus | 2024 | 36% (38%) | 60% (62%) | 4% | [31] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 37% | 56% | 7% | [9] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 62% (64%) | 37% (36%) | 2% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 53% | 32% [14% support some rights] | 13% | ±5% [f] | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 38% (39%) | 59% (61%) | 3% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 36% | 37% [16% support some rights] | 27% not sure | ±5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (42%) | 56% (58%) | 3% | [5] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (80%) | 19% [13% support some rights] (21%) | 9% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 87% (90%) | 10% | 3% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 88% (91%) | 9% (10%) | 3% | [9] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 23% (25%) | 69% (75%) | 8% | [5] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 18% | – | – | [10] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 78% (84%) | 15% [8% support some rights] (16%) | 7% not sure | ±5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 92% (94%) | 6% | 2% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 1% | [9] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 54% (61%) | 34% [16% support some rights] (39%) | 13% not sure | ±3.5% | [26] | |

| CNA | 2023 | 63% | 37% | [32] | |||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (51%) | 43% (49%) | 12% | [5] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 58% | 29% [20% support some rights] | 12% not sure | ±5%[f] | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 60% (65%) | 32% (35%) | 8% | [5] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 16% | – | – | [10] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 18% (26%) | 52% [19% support some rights] (74%) | 30% not sure | ±5% [f] | [4] | |

| Rating | 2023 | 37% (47%) | 42% (53%) | 22% | ±1.5% | [33] | |

| YouGov | 2023 | 77% (84%) | 15% (16%) | 8% | [34] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 66% (73%) | 24% [11% support some rights] (27%) | 10% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 74% (77%) | 22% (23%) | 4% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (62%) | 32% [14% support some rights] (39%) | 18% not sure | ±3.5% | [4] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (65%) | 34% (35%) | 3% | ±3.6% | [5] | |

| LatinoBarómetro | 2023 | 78% (80%) | 20% | 2% | [35] | ||

| Equilibrium Cende | 2023 | 55% (63%) | 32% (37%) | 13% | [36] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 65% (68%) | 30% (32%) | 5% | [26] |

- ^ Legalized in Aruba and Curaçao through ruling of the Supreme Court of the Netherlands on 12 July 2024

- ^ Federal recognition codified by the United States Congress on 13 December 2022

- ^ Passed by the Slovenian Parliament on 4 October 2022

- ^ a b Because some polls do not report 'neither', those that do are listed with simple yes/no percentages in parentheses, so their figures can be compared.

- ^ Comprises: Neutral; Don't know; No answer; Other; Refused.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k [+ more urban/educated than representative]

Africa

[edit]South Africa is the only African country that legally recognizes same-sex marriage.[37]

South Africa

[edit]In December 2005, in the case of Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie, the Constitutional Court of South Africa ruled unanimously that bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional. The Court gave Parliament one year to change the laws, or same-sex marriage would be legalized by default.

In November 2006, Parliament passed the Civil Union Act, under which both same-sex and opposite-sex couples may contract unions. A union under the Civil Union Act may, at the choice of the spouses, be called either a marriage or a civil partnership; whichever name is chosen, the legal effect is identical to that of a traditional marriage under the Marriage Act. Both religious and civil officials may refuse to perform same-sex marriages.[38]

Namibia

[edit]In May 2023, the Supreme Court of Namibia ruled in favor of recognizing same-sex marriages performed in other jurisdictions.[39]

Americas

[edit]Argentina

[edit]On 22 July 2010, Argentina became the first country in Latin America to legalise same-sex marriage. The law also allows same-sex couples to adopt.[40] And in many jurisdictions, including the city of Buenos Aires, it is also legal for non-residents and tourists.[41]

Brazil

[edit]On 25 October 2011, Brazil's Supreme Court of Justice ruled that two women can enter into civil marriage under the current law, thus overturning the decision of two lower court's ruling against the women.[42] Following this ruling, a growing number of courts of Brazilian states, such as the most populous state of São Paulo, implemented directives which allowed for same-sex civil marriages in the same manner as other marriages.

Same-sex couples can currently have registered partnerships and full rights to adopt children in all states, and same-sex marriages based on court orders have occurred in several states in individual cases.

On 14 May 2013, Brazil's National Justice Council (CNJ) ruled in favor of recognizing same-sex marriage nationwide.[43]

Canada

[edit]In Canada between 2003 and 2005, court rulings in Ontario, British Columbia, Quebec, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, and Yukon ruled the prohibition of same-sex marriage to be contrary to the Charter of Rights, thus legalizing it in those jurisdictions (which covered 90% of the population). In response to these rulings, the governing Liberal party minority government introduced legislation to allow same-sex couples to marry. On 20 July 2005, the Canadian Parliament passed the Civil Marriage Act, defining marriage nationwide as "the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others." This was challenged on 7 December 2006 by a motion tabled by the newly elected Conservative party, asking the government to introduce amendments to the Marriage Act to restrict marriage to opposite-sex couples; it was defeated in the House of Commons by a vote of 175 to 123.

Canada does not have a residency requirement for marriage; consequently, many foreign couples have gone to Canada to marry, regardless of whether that marriage will be recognized in their home country. In fact, in some cases, a Canadian marriage has provided the basis for a challenge to the laws of another country, with cases in Ireland and Israel. The plaintiff in the case of United States v. Windsor, which challenged the Defense of Marriage Act, wed her wife in Ontario.

Since 11 November 2004, the Canadian federal government's immigration department, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), considers same-sex marriages performed in Canada valid for the purposes of sponsoring a spouse to immigrate.[44] Canadian immigration authorities previously considered long-term, same-sex relationships to be equivalent to similar heterosexual relationships as grounds for sponsorship.[citation needed]

Colombia

[edit]The Colombian Constitutional Court ruled in February 2007 that same-sex couples are entitled to the same inheritance rights as heterosexuals in common-law marriages. This ruling made Colombia the first South American nation to legally recognize same-sex couples. In January 2009, the Court ruled that same-sex couples must be granted all rights offered to cohabiting heterosexual couples.[45] On 26 July 2011, the Court ordered the Congress to pass legislation giving same-sex couples similar rights to marriage within two years (by 20 June 2013). The law was defeated.[46][47][48] In April 2016, the Colombian Constitutional Court voted 6–3 to allow same-sex marriage, with the ruling taking effect immediately.[49]

In 2015, the Colombian Constitutional Court ruled that same-sex couples could adopt children.

Costa Rica

[edit]In 2016 the government motioned at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to pass judgement over the rights of same-sex couples. The Court agreed and in 2018 the Court's binding sentence was that Costa Rica (and presumably all the other member states of the Pact of San José) was required to provide same rights to same-sex couples that heterosexual couples enjoy including marriage.[50] Costa Rica's Constitutional Court subsequently ruled that same-sex couples must be allowed to marry, and gave the government a deadline of 26 May 2020, to make legislative changes. As the deadline lapsed without legislative action, same-sex couples were allowed to marry starting 26 May 2020.[51]

Cuba

[edit]Same-sex marriage has been legal in Cuba since 27 September 2022, after a majority of voters approved the legalization of same-sex marriage at a referendum two days prior.[52] The Constitution of Cuba prohibited same-sex marriage until 2019, and in May 2019 the government announced plans to legalize same-sex marriage.[53] A draft family code containing provisions allowing same-sex couples to marry and adopt was approved by the National Assembly of People's Power on 21 December 2021.[54] The text was under public consultation until 6 June 2022, and was approved by the Assembly on 22 July 2022.[55] The measure was approved by two-thirds of voters in a referendum held on 25 September 2022.[56][52] President Miguel Díaz-Canel signed the new family code into law on 26 September,[57][58] and it took effect upon publication in the Official Gazette the following day.[59]

Cuba was the first independent nation in the Caribbean, the eighth country in Latin America,[a] the first communist state, the first of the former Eastern Bloc (excluding East Germany and Slovenia)[b] and the 32nd country worldwide to legalize same-sex marriage.

Ecuador

[edit]Mexico

[edit]

Same-sex marriage has been legalized in all states of Mexico and in Mexico City. Since August 2010, same-sex marriages performed within Mexico are recognized by all 31 states without exception.

On 9 November 2006, Mexico City's unicameral Legislative Assembly passed and approved (43–17) a bill legalizing same-sex civil unions, under the name Ley de Sociedades de Convivencia (Law for Co-existence Partnerships), which became effective on 16 March 2007.[68] The law recognizes property and inheritance rights to same-sex couples. On 11 January 2007, the northern state of Coahuila, which borders Texas, passed a similar bill (20–13), under the name Pacto Civil de Solidaridad (Civil Pact of Solidarity).[69] Unlike Mexico City's law, once same-sex couples have registered in Coahuila, the state protects their rights no matter where they live in the country.[69] Twenty days after the law had passed, the country's first same-sex civil union took place in Saltillo, Coahuila.[70]

On 21 December 2009, Mexico City's Legislative Assembly legalized (39–20) same-sex marriages and adoption by same-sex couples.[71] Eight days later, the law was enacted and became effective in March 2010.[72]

Since then, Mexican states have been legalising same-sex marriage one by one, via a combination of gubernatorial decrees, legislative measures, and judicial rulings. Most recently, on 26 October 2022, the Congress of Tamaulipas approved same-sex marriage, making it the final jurisdiction in the country to do so.[73]

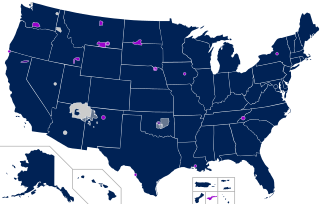

United States

[edit]

On 26 June 2015, the US Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage is a constitutional right under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, thereby making same-sex marriage legal throughout the United States.[74]

Prior to 26 June 2015, same-sex marriages were legal in the District of Columbia, Guam, and thirty-six states.

In 2005, California became the first state to pass a bill authorizing same-sex marriages without a court order, but this bill was vetoed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. In 2008, the Supreme Court of California overturned a 2000 law banning same-sex marriages.[75] The legal effect of the court ruling was curtailed by another voter initiative called Proposition 8 later that year.[76] Proposition 8 was upheld by the California Supreme Court in 2009, holding that same-sex couples have all the rights of heterosexual couples, except the right to the "designation" of marriage.[77] On 26 June 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Hollingsworth v. Perry that Proposition 8 was unconstitutional, allowing same-sex marriages to resume in California.

Federal recognition

[edit]In 1996, the U.S. Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). Section 2 of DOMA defined marriage as a union between a man and a woman, and its purpose was to enable states to deny recognition of same-sex marriages performed in other states.[78] Section 3 of DOMA also denied federal recognition to same-sex couples who were legally married under state law.

On 26 June 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court declared Section 3 of DOMA to be unconstitutional in United States v. Windsor. The court said that the provision was "a deprivation of the equal liberty of persons that is protected by the Fifth Amendment."[79] With this ruling the federal government recognized same-sex marriages performed by states that allowed same-sex marriage. It also affected several federal rights, including enabling a U.S. citizen to petition a same-sex spouse for immigration.[80] The Court in the United States v. Windsor case did not, however, address the constitutionality of DOMA Section 2, which allowed a state to deny recognition of same-sex marriages granted in other states.

In February 2015, the United States Department of Labor issued its final rule amending the definition of "spouse" under the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) in response to the Windsor decision. The new rule became effective 27 March 2015.[81] The revised definition of "spouse" extended FMLA leave rights and job protections to eligible employees in a same-sex marriage or a common-law marriage entered into in a state where those statuses were legally recognized, regardless of the state in which the employee worked or resided.[82] Accordingly, even if an employer had employees working where same-sex or common law marriage was not recognized, those employees' spouses would trigger FMLA coverage if an employee was married in one of the states that recognized same-sex marriage or common law marriage.[83]

The Obergefell v. Hodges decision on 26 June 2015 eliminated the distinction between same-sex marriage and opposite-sex marriage at the federal level, holding that marriage was a constitutional right, and that same-sex couples were entitled to equal rights under the law.[84]

In December 2022, the Respect for Marriage Act was signed into law, repealing DOMA and codifying the rights to both same-sex and interracial marriage under federal law.

Civil unions

[edit]Several states offer alternative legal certifications that recognize same-sex relationships. Before states enacted these laws, U.S. cities began offering recognition of these unions. These laws bestow marriage-like rights to these couples, and are referred to as civil unions, domestic partnerships, or reciprocal beneficiaries depending on the state. The extent to which these unions resemble marriage vary by state, and several states have enhanced the rights afforded to them over time. The U.S. jurisdictions that used these forms of same-sex union recognition instead of marriage were Colorado, Wisconsin, and Nevada, all beginning in 2009.

U.S. Territories

[edit]An attempt to ban same-sex marriages and any other legal recognition of same-sex couples in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico failed in 2008. Puerto Rico already banned same-sex marriage by statute.[85] Same-sex marriage became legal in Puerto Rico in 2015 due to Obergefell v. Hodges.

Same-sex marriage is not performed in American Samoa, an unorganized territory of the U.S. The application of the U.S. Supreme Court's decision to the territory is unclear and has not been challenged.[86] However, the passage of the Respect for Marriage Act in 2022 meant same-sex marriages conducted outside of American Samoa must be recognized in the territory.[citation needed]

Tribal Nations in the United States

[edit]Several Native American tribes have also legalized same-sex marriage. Those are:

- Blackfeet Nation[87]

- Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Tribes of Alaska[88]

- Cherokee Nation[89]

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes[90]

- Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians[91]

- Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation

- Coquille Tribe[92][93]

- Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes of the Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation

- Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation

- Grand Portage Band of Chippewa

- Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel[94]

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community

- Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians[95]

- Mashantucket Pequot

- Oneida Nation of Wisconsin

- Osage Nation[96]

- Pascua Yaqui Tribe

- Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians[97]

- Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe

- The Puyallup Tribe of Indians

- Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community

- San Carlos Apache Tribe

- Suquamish Tribe

- Wind River Indian Reservation

Uruguay

[edit]Uruguay became the first country in South America to allow civil unions (for both opposite sex and same-sex couples) on 1 January 2008.

Children can be adopted by same-sex couples since 2009.[98][99] A same-sex marriage bill passed in the Chamber of Deputies in December 2012,[100][101] as well as in the Senate in April 2013 but with minor amendments. The amended bill was approved by the Chamber of Deputies in a 71–21 vote on 10 April and was signed by the President on 3 May 2013.[102] The law took effect on 5 August 2013.[103]

Asia

[edit]

Same-sex sexual activity legal

Taiwan is the only Asian country that performs same-sex marriages, while Israel recognizes same-sex marriages performed overseas.

On 24 May 2017 the Constitutional Court in Taiwan ruled that same-sex couples have a right to marry, and gave the legislature two years to amend Taiwanese marriage laws accordingly.[104] On 24 May 2019, Taiwan became the first country in Asia to recognize same-sex marriage. Nepal and Thailand both legalised same-sex marriage in 2024.[105][106]

Cambodia

[edit]In 2004 King Norodom Sihanouk announced that he supported legislation extending marriage rights to same-sex couples.[107]

In 2011, a ban prohibiting gay marriage was abolished, making same-sex marriages not illegal, but also not protected by law. Some village chiefs may occasionally issue marriage certificates to same-sex couples if one of them is willing to identify as the opposite sex on the marriage license.[108]

China

[edit]Same-sex marriage is not legally recognized. Article 2 of the Marriage Law declares "one husband and one wife" as one of the principles guiding marriages. The principle, first codified in 1950, was intended to outlaw polygamy, but is now also interpreted to disallow same-sex marriages. Many other articles of the same law also assume the marriage is a heterosexual union.[citation needed]

The National People's Congress proposed legislation allowing same-sex marriages in 2003. However, the proposal failed to collect the 30 votes needed to be added to the agenda.[citation needed]

On 5 January 2016, a court in Changsha agreed to hear a lawsuit against the Bureau of Civil Affairs of Furong District for its June 2015 refusal to let a gay man marry his partner.[109] On 13 April 2016, the court ruled against the couple. They vowed to appeal, citing the importance of his case for LGBT progress in China.[110]

Currently, Beijing will grant spousal visas to same-sex couples. These documents allow foreign same-sex married couples to live in China, though only one member of the couple may work.[111]

Hong Kong

[edit]The right to marry in Hong Kong is a constitutionally protected right. The Basic Law, the city's constitutional charter, does not define marriage as between a man and a woman, but the Marriage Ordinance does. Under Section 40 of the Marriage Ordinance (Cap. 181), marriage shall be a "Christian marriage or the civil equivalent of a Christian marriage"; and this "implies a formal ceremony recognized by law as involving the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others ". Therefore, same-sex couples are excluded from the legal institution of marriage, along with the benefits of marriage.[53][112]

In 2004 and 2013, under the UK Civil Partnership Act 2004 and Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013 respectively, British Nationals including Hong Kong residents holding BN(O) status already have the right to register as civil partners and get married with their same sex partners, under the UK law. However, the British consulate in Hong Kong does not perform consular civil partnerships or same-sex marriage due to the "strong objections" the HKSAR government raised with the British consulate-general, as apparently UK law prohibits embassies and consulates from performing consular marriages if objection is raised by the local government.[53][113][114][115]

In 2009, changes to Hong Kong's Domestic and Cohabitation Relationships Ordinance were made to protect same-sex partners.[116] On 13 May 2013, the Court of Final Appeal, in a 4:1 decision, gave transgender people the right to marry as their identified gender rather than their biological sex at birth, but only in biologically heterosexual relationships (i.e., a transgender woman could not marry a cisgender woman).[117]

In 2018, the government began granting spousal dependant visas to spouses of residents in same-sex legal unions. In July 2018, the Court of Final Appeal upheld a lower court's judgment in favour of a lesbian expat, stating that government's differential treatment towards her – denying her a spousal visa on the basis of marital status – amounted to unlawful discrimination.[118] This gives the dependant visa holders the right to work and earn, and be eligible to apply for permanent residency after residing in Hong Kong continuously for 7 years.[119]

On 22 November 2018, a gay married man filed to the High Court a judicial review application, arguing that a decision by the Housing Authority was unconstitutional under the Hong Kong Bill of Rights and the Basic Law, after he and his husband married in Canada were rejected by the HKSAR government for an application for public housing under the category of "ordinary family" in September.[120]

India

[edit]India provides same-sex couples rights and benefits equal to married couples as a live-in couple (anagolous to cohabitation or common law marriage) as per a supreme court judgement in August 2022, which offers some sembience of equality in a country where the vast majority of marriages are not registered with government.[121][122]

While it does not recognise same-sex marriage or civil unions, the vast majority of heterosexual marriages are not registered with government and common law marriage based on traditional customs remains the dominant form of marriage. A number of common law marriages between same-sex couples in rural communities have been reported by the media since independence from colonialism. The Delhi High Court is currently hearing multiple petitions which seek to amend marriage laws for same-sex marriage in India.

India does not possess a unified marriage law, and as such every citizen has the right to choose which law will apply to them based on their community or religion. Although marriage is legislated at the federal level, the existence of multiple marriage laws complicates the issue.[123]

Israel

[edit]Marriages in Israel are performed under the authority of the religious authorities to which the couple belong. For Jewish couples the responsible religious authority is the orthodox Chief Rabbinate of Israel, which does not permit same-sex marriages. However, on 21 November 2006 the Supreme Court of Israel ruled that five same-sex Israeli couples who had married in Canada were entitled to have their marriages registered in Israel.[124]

Japan

[edit]Article 24 of the Japanese constitution states that "Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis." The purpose of the clause was to amend previous feudal arrangements where the father or husband was legally recognized as the head of the household. However, the new constitution had the unintended consequence of defining the marriage as a union of "both sexes", i.e. man and woman.[citation needed] However, on 27 March 2009, a justice ministry official was reported to have said that Japan had granted permission for its citizens to marry foreign same-sex partners in countries where same-sex marriage is legal.[125] Japan does not allow same-sex marriage within its borders, and had until that point also refused to issue a key document required for citizens to wed overseas if the applicant's intended spouse was of the same gender. Under the change, the Ministry of Justice instructed local authorities to issue the key certificate—which states a person is single and of legal age—for those wanting to enter same-sex marriages.

Nepal

[edit]In November 2008, Nepal's highest court issued a final judgement on matters related to LGBT rights.[126][127] A new Nepalese constitution, approved by the Constituent Assembly on 16 September 2015, included several provisions pertaining to LGBT rights. Based on the ruling of the Supreme Court of Nepal in late 2008, the government was debating legalising same-sex marriage. Several sources suggested that the new constitution would include this provision. However, the new constitution did not address that topic explicitly.[128][52]

In November 2023, Nepal officially recognised a same-sex marriage between a transgender woman and a cisgender man, months after the Supreme Court decision which proposed the legislation.[129] In 2024, Nepal's Ministry of Home Affairs passed an order for all counties to register same-sex marriages.[105][130]

Philippines

[edit]The Philippines does not recognize same-sex marriage. The Family Code of the Philippines defines marriage as "a special contract of permanent union between a man and a woman".[131]

Taiwan

[edit]In 2003, the government of Taiwan (officially the Republic of China) led by the Presidential office, proposed legislation granting marriages to same-sex couples under the Human Rights Basic Law, but it did not proceed.

On 22 December 2014, a proposed amendment to the Civil Code to legalize same-sex marriage went under review by the Judiciary Committee. If the amendment had passed the committee stage it would have been voted on at the plenary session of the Legislative Yuan in 2015. The amendment, called the marriage equality amendment, would have inserted neutral terms into the Civil Code replacing ones that imply heterosexual marriage, effectively legalizing same-sex marriage. It would also have allowed same-sex couples to adopt children. Yu Mei-nu of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), the convener of the legislative session, expressed support for the amendment, as did more than 20 other DPP lawmakers as well as two from the Taiwan Solidarity Union and one each from the Kuomintang and the People First Party.[132]

The Constitutional Court's J. Y. Interpretation No. 748 ruled on 24 May 2017 that laws limiting marriage to between a man and a woman were unconstitutional.[133] The panel of judges gave the Legislative Yuan two years to amend or enact new laws.[134] The court further stipulated that should the Legislative Yuan fail to amend or enact laws legalizing same-sex marriage within two years, same-sex couples would be able to marry through existing marriage registration processes at any household registration office.

On 17 May 2019, the Legislative Yuan passed the Act for Implementation of J. Y. Interpretation No. 748. The name of the law, referring to the Constitutional Court ruling two years earlier, was an attempt at compromise, employing neutral-sounding terminology.[135][136] It was subsequently signed by the President on 22 May 2019.[137] The law came into effect on 24 May 2019, making Taiwan the first country in Asia to recognize same-sex marriage.

Europe

[edit]

Same-sex civil marriages are legally recognized nationwide in Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. In a number of other European countries, same-sex civil unions give similar or identical rights to marriage. Liechtenstein is set to introduce same-sex marriage rights in 2025.[138]

A poll conducted by EOS Gallup Europe in 2003 found that 57% of the population in the then 15-member European Union supported same-sex marriage. Support among the member states who joined in 2004 was around 28%, meaning that 53% of citizens in the 28-member EU supported legalizing same-sex marriage.[139]

Albania

[edit]Albania's government announced its intention to propose a bill allowing same-sex marriage in 2009. However, no bill has been presented as of 2023.[140]

Austria

[edit]Austria began performing same-sex marriages and different-sex registered partnerships on 1 January 2019, after the Constitutional Court deemed that the existing laws treated same-sex couples and different-sex couples differently, and were therefore discriminatory.[141]

Belgium

[edit]On 1 June 2003, Belgium became the second country in the world to legally recognise same-sex marriage.

Cyprus

[edit]Civil cohabitations have been legal in Cyprus since 11 December 2015. The bill to establish civil cohabitation was approved by the parliament on 26 November 2015 with a 39–12 vote.[142][143] It was published in the official gazette on 11 December 2015 and took effect upon publication.[144]

Czech Republic

[edit]On 15 March 2006, the parliament of the Czech Republic voted to override a presidential veto and allow same-sex partnerships to be recognised by law, effective 1 July 2006, granting registered couples inheritance and health care rights similar to married couples. The legislation did not grant adoption rights. The parliament had previously rejected similar legislation four times.[145][146]

Denmark

[edit]On 15 June 2012, Denmark became the eleventh country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage. The autonomous territory Greenland legalised same-sex marriage on 1 April 2016, and the Faroe Islands followed on 1 July 2017.

Estonia

[edit]Estonia has recognised same-sex registered partnerships since January 1, 2016.[147]

In June 2023, the Estonian Parliament passed a bill legalizing same-sex marriage and joint adoption, and giving full effect to the registered partnership law. The law commenced on 1 January 2024.[148][149]

Finland

[edit]Registered partnerships were performed in Finland between 2002 and 2017. Legislation for same-sex marriage was submitted by individual members of the Parliament in March 2012 but it was turned down by the Legal Affairs Committee in February 2013. A similar bill was introduced to the Parliament in December 2013 as a citizens' initiative, with the support of 160,000 people. In June 2014 the Legal Affairs Committee recommended to reject it, but on 28 November 2014 the full Parliament rejected that recommendation by a vote of 92–105, thus paving the way for the legalisation of same-sex marriage. The initiative was approved by the full session at the second reading on 12 December 2014. A new citizens' initiative was started on 29 March 2015 aiming to rescind the new marriage law. The new initiative collected almost 110,000 signatures by 29 September 2015 but it was rejected by the Legal Affairs Committee and later voted down by the full Parliament on 17 February 2017, by 120–48. The new marriage law took effect on 1 March 2017.

France

[edit]Since 1999, same-sex civil unions (PACS) have been legal in France. In June 2011, an Ifop poll found that 63% of respondents were in favour of same-sex marriage.[150] France legalised same-sex marriage on 23 April 2013.[151] The bill was confirmed in the Constitutional Court of France on 17 May 2013 and signed by the French President on 18 May 2013.

Germany

[edit]Equal marriage (including full adoption rights) was passed by the Lower House of the German Parliament (the Bundestag) on 30 June 2017, was approved by the Upper House (the Bundesrat) on 7 July, and was signed into law on 20 July 2017 by President Frank-Walter Steinmeier. It came into effect on 1 October 2017. Registered life partnerships (Eingetragene Lebenspartnerschaft) (effectively, a form of civil union) have been instituted since 2001, giving same-sex couples most of the rights and obligations of marriage. Step-child adoption was legalized in 2004 and extended to children adopted by one partner first (successive adoption) in 2013.

Greece

[edit]In Greece, there is a legal recognition of same-sex couples since 24 December 2015. Attempts to give equal rights to registered partners or to legalize same-sex marriage began in Spring 2008, after the Greek Minister of Justice, Transparency and Human Rights announced that a bill was to be introduced to the Hellenic Parliament in order to regulate civil partnerships for opposite-sex couples, but refused to include provisions for same-sex couples as well. In 2013 the case was brought to the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled that the exclusion of same-sex couples from the bill was discriminatory and a violation of human rights. On 9 November 2015, a new bill granting same-sex couples all the rights of marriage except adoption was published. After a public consultation, which ended on 20 November 2015, the bill was submitted to the Hellenic Parliament on 9 December 2015, and approved 14 days later, on 23 December, with 194 MPs voting yes, 55 voting no and 51 being absent.[152][153] The following day, the law was signed by the President of Greece and published in the government gazette. It took effect upon publication.[154]

Hungary

[edit]Unregistered cohabitation has been recognized since 1996. It applies to any couple living together in an economic and sexual relationship[citation needed](common-law marriage), including same-sex couples. No official registration is required. The law gives some specified rights and benefits to two persons living together. These rights and benefits are not automatically given – they must be applied for to the social department of the local government in each case. An amendment was made to the Civil Code: "Partners – if not stipulated otherwise by law – are two people living in an emotional and economic community in the same household without being married." Widow-pension is possible, partners cannot be heirs by law (without the need for a will), but can be designated as testamentary heirs.

The Hungarian Parliament on 21 April 2009 passed legislation by a vote of 199–159, called the Registered Partnership Act 2009 which allows same-sex couples to register their relationships so they can access the same rights, benefits and entitlements as opposite-sex couples (except for the right to marriage, adoption, IVF, surrogacy, taking a surname or become the legal guardian of their partner's child). The legislation does not allow opposite-sex couples to register their relationships (out of fear that there might be duplication under the law). The law came into force on 1 July 2009.[155]

Since 1 January 2012 the Hungarian Constitution bans same-sex marriage.

Iceland

[edit]On 11 June 2010, a law was passed to make same-sex marriage legal in Iceland. The law took effect on 27 June 2010.[156]

Ireland

[edit]The Civil Partnership and Certain Rights and Obligations of Cohabitants Act 2010 was first debated in Dáil Éireann on 3 December 2009. It passed in Dáil Éireann without a vote on 1 July 2010 due to all parties supporting the bill. The bill passed in Seanad Éireann on 8 July 2010 with a vote of 48–4. It was signed by the President of Ireland on 19 July 2010.

The law took effect on 1 January 2011.[157] It grants many rights to same-sex couples through civil partnerships but does not recognise both civil partners as the guardians of a child being raised by the couple. Irish law allows married couples and individuals to apply to adopt and allows gay couples to foster. The Act also gives new protections to cohabitating couples, both same-sex and opposite-sex.[158]

A referendum that took place on 22 May 2015 has amended the Irish constitution to make same-sex marriage legal.[159] The Marriage Act 2015 was signed into law on 29 October 2015.[160]

Italy

[edit]On 11 May 2016, Italian MPs voted 372 to 51, and 99 abstaining, to approve Civil Unions in Italy.[161] This came nearly a year after the European Court of Human Rights found Italy to be in breach of the European Convention of Human Rights.[162] The Italian law on Civil Unions (Legge 20 maggio 2016 N. 76) delivers all of the rights of marriage to same sex partners, except for joint adoption and stepchild adoption.[163]

Latvia

[edit]In December 2005, the Latvian Parliament passed a constitutional amendment defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman. President Vaira Vike-Freiberga signed the amendment shortly afterward.

On 12 November 2020, the Constitutional Court of Latvia issued a ruling in favor of same-sex couples receiving rights and benefits equal to married opposite-sex couples. The Court gave the Saeima until 1 June 2022 to enact legislation. In December 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that if legislation failed before the deadline that couples could register with courts to recognize their relationships. The first civil union was recognized on 30 May 2022.

Malta

[edit]On 14 April 2014, the Maltese parliament voted in favour of civil unions at par with marriage (equal to marriage in all but the name) with all rights and obligations, including the right to adoption and recognition of same-sex marriage contracted abroad. The first foreign same-sex marriage was registered on 29 April 2014 and the first civil unions began on 14 June 2014.[164] On 12 July 2017, Malta legalized same-sex marriage with a near unanimous parliamentary vote.[165]

Netherlands

[edit]The Netherlands became the first country in the world to legalise same-sex marriages on 1 April 2001. The possibility exists in its European territory as well as in the special municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba (known as the Caribbean Netherlands) and the constituent countries of Aruba and Curaçao, while those marriages are also recognised in Sint Maarten.

Norway

[edit]Same-sex marriage is legally performed in Norway. The Norwegian government proposed a gender-neutral marriage law on 14 March 2008, that would give same-sex couples the same rights as heterosexuals, including church weddings, adoption and assisted pregnancies. On 29 May 2008, the Associated Press reported that two Norwegian Opposition parties came out in favor of the new bill, assuring the bill's passage when the vote was held on 11 June. Prior to this, there were some disagreements with members of the three-party governing coalition on whether the bill had enough votes to pass. With this, it became almost certain that the bill would pass.[166]

The first hearings and the vote were held, and passed, on 11 June 2008. 84 votes for and 41 against. This also specified that when a woman who is married to another woman becomes pregnant through artificial insemination, the partner would have all the rights of parenthood "from the moment of conception". The law became effective from 1 January 2009.[167]

Norway was also the second country to legalize registered partnerships, doing so in 1993. Since 1 January 2009, all registered partnerships[citation needed] from 1993 to 2008 were upon request by the couples upgraded to marriage status.

Portugal

[edit]In March 2001, the Socialist government of Prime Minister António Guterres introduced legislation that would extend to same-sex couples the same rights as heterosexual couples living in a de facto union for more than two years.[citation needed]

Same-sex marriage became a source of debate in February 2006 when a lesbian couple was denied a marriage license. They took their case to court alleging violation of the 1976 constitution which prohibits discrimination based on one's sexual orientation. Prime Minister José Sócrates of the Socialist Party was reelected in September 2009 and included same-sex marriage in his party's program. A bill recognizing same-sex marriage was proposed by the government and approved by parliament on 8 January 2010.[168] However, Portugal's parliament rejected alternative proposals that included a provision to allow homosexual couples to adopt as a couple (single homosexuals can legally adopt).[169] Although personally against it, the Portuguese President ratified the bill on 17 May 2010. The law became effective on 5 June 2010, after publication in the official gazette, on 31 May. The first marriage was celebrated on 7 June 2010 between Teresa Pires and Helena Paixão, the same lesbian couple that was denied a marriage licence in 2006.

Slovenia

[edit]In July 2006, Slovenia became the first former Yugoslav country to introduce domestic partnerships nationwide.[170] In December 2009 the Slovenian government approved a new Family Code, which includes same-sex marriage and same-sex adoption. The bill was approved by parliament, but rejected by voters in a 2015 referendum. On 24 February 2017, a new law came into effect which gives same-sex partnerships all the legal rights of marriages, with the exception of adoption and in-vitro fertilisation.[171][172] On 8 July 2022, the Slovenian Constitutional Court ruled that same-sex marriage and joint adoption by same-sex couples were legal. Parliament was given six months to bring legislation in line with the constitution, although the ruling took effect immediately.[citation needed]

Spain

[edit]Spain became the third country in the world (after the Netherlands and Belgium) to legalize same-sex marriage. After being elected in June 2004, Spanish prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero restated his pre-election pledge to push for legalization of same-sex marriage.[173] On 1 October 2004, the Spanish Government approved a bill to legalize same-sex marriage, including adoption rights. The bill received full parliamentary approval on 30 June 2005 and passed into law on 2 July, becoming fully legal on 3 July. Polls at the time suggested that 62% to 76% of Spain supports same-sex marriage,[174][175][176] while recent polls indicate that 77% of Spaniards supported same-sex marriage, 13% were opposed and 10% did not know or refused to answer[177] and the 2019 Eurobarometer found that 86% of Spaniards thought same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe, while 9% were opposed.[178]

Sweden

[edit]Following a bill introduced jointly by six of the seven parties in the Riksdag, a gender-neutral marriage law was adopted on 1 April 2009.[179] It came into force on 1 May, replacing the old legislation on registered partnerships.[180] On 22 October, the assembly of the Church of Sweden (which is no longer officially the national church but whose assent was needed for the new system to function smoothly with regard to church officials) voted strongly in favor of the new law.[181]

Switzerland

[edit]Switzerland allowed registered partnerships for same-sex couples since 1 January 2007. A legislative initiative to legalize same-sex marriage was introduced in 2013 in the Swiss parliament. This legislation was passed on 18 December 2020, but the act remains subject to a referendum if 50,000 citizens request it within three months after its passage.[182]

On 26 September 2021, 64.1% of the population voted in favour of allowing same-sex couples to marry, with 35.9% voting against. Switzerland therefore now allows same-sex marriage, as well as access to sperm banks for lesbian couples, and same-sex couples to adopt children.[183]

United Kingdom

[edit]England and Wales

[edit]On 18 November 2004 the United Kingdom Parliament passed the Civil Partnership Act, which came into force in December 2005 and allows same-sex couples in England and Wales to register their partnership. The government stressed during the passage of the bill that it is not same-sex marriage, and some same-sex rights activists have criticized the act for not using the terminology of marriage. However, the rights and duties of partners under this legislation are exactly the same as for married couples. An amendment proposing similar rights for family members living together was rejected. The press widely referred to these unions as "gay marriage." [184] During and following the 2010 election, all parties stated they were in favor of allowing same-sex marriage in the UK.[185][186] Following a public consultation, as of 2013 a bill allowing same-sex marriage in England and Wales, and also providing an exemption for conducting of same-sex marriage ceremonies for religious bodies whose doctrines oppose such relationships, passed its second reading on 5 February 2013 in a 400–175 vote. The bill passed its third reading in the House of Lords on 15 July 2013[187] and the Commons accepted all of the Lords' amendments on the following day, with Royal Assent granted on 17 July 2013. The law went into effect on 29 March 2014.

Scotland

[edit]In Scotland, which is a separate legal jurisdiction, the devolved Scottish Parliament also introduced Civil Partnerships, and performed also a consultation on the issue of same-sex marriage. On 25 July 2012 the Scottish Government announced it would bring forward legislation to legalise both civil and religious same-sex marriage in Scotland. The Government reiterated its intention to ensure that no religious group or individual member of the clergy would be forced to conduct such ceremonies; it also stated its intention to work with Westminster to make necessary changes to the Equality Act to ensure that this would be guaranteed.[188][189]

On 4 February 2014, the Scottish Parliament passed the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 105 to 18, legalizing same-sex marriage with effect from 16 December 2014.

Northern Ireland

[edit]Same-sex marriage is legal in Northern Ireland. Under the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019, regulations were passed to legalise same-sex marriage on 13 January 2020. The first same-sex wedding took place on 11 February 2020.[190]

Oceania

[edit]

Australia

[edit]Australia became the second nation in Oceania to legalise same-sex marriage when the Australian Parliament passed a bill on 7 December 2017.[191] The bill received royal assent on 8 December, and took effect on 9 December 2017.[192][193] The law removed the ban on same-sex marriage which previously existed and followed a voluntary postal survey held from 12 September to 7 November 2017, which returned a 61.6% Yes vote for same-sex marriage.[194] The same legislation also legalised same-sex marriage in all of Australia's external territories.[193]

Fiji

[edit]On 26 March 2013, Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama expressed his opposition to same-sex marriage. Answering a question from a caller on a radio talk show, he stated that same-sex marriage "will not be allowed because it is against religious beliefs".[195][196]

New Zealand

[edit]Civil unions, which grant all of the same rights and privileges as marriage excluding adoption, have been legal since 2005.

On 17 April 2013, the Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Bill, a private member's bill sponsored by lesbian Labour MP Louisa Wall that would legalise same sex marriage was passed by Parliament, 77 votes to 44.[197] The bill received Royal Assent from the Governor-General on 19 April and took effect on 19 August 2013.[198]

In the first year after the law came into effect, 926 same-sex marriages were registered in New Zealand, including 532 marriages (57.5%) between New Zealand citizens, and 237 marriages (25.6%) between Australian citizens.[199][200]

Samoa

[edit]Samoa is a deeply conservative Christian nation.[201] In 2012, Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi was dismissive of the idea of same-sex marriage being adopted in Samoa, and indicated that he would not support it.[202] He reiterated this position, on explicitly religious grounds, in March 2013.[203]

Religious recognition

[edit]The religious status of same-sex marriage has been changing since the late 20th century and varies greatly among different world religions. This section distinguishes religions that recognize same-sex marriage or unions in some way from those that do not.

Recognized

[edit]Some religious institutions that recognize same-sex relationships avoid using the terms "marriages" or "weddings", and instead call them "blessings" or "unions." Some religious groups allow individual congregations to set their own policies regarding the blessing of same-sex relationships.

The following institutions have recognized same-sex relationships in some fashion, either as individual congregations or as a denomination-wide policy:

- Anglicanism (See Homosexuality and Anglicanism): The Anglican Communion is divided over the issue of homosexuality. "The more liberal provinces that are open to changing Church doctrine on marriage in order to allow for same-sex unions include Brazil, Canada, New Zealand, Scotland, South India, South Africa, the US and Wales."[204]

- Anglican Church in New Zealand: In 2014, the "General Synod passe[d] a resolution that will create a pathway towards the blessing of same-gender relationships, while upholding the traditional doctrine of marriage...It therefore says clergy should be permitted [while the blessings are being developed] 'to recognise in public worship' a same-gender civil union or state marriage of members of their faith community..."[205] On a diocesan level, the Dunedin Diocese already permits a blessing for relationships irrespective of the partners' gender.[206] "Blessings of same-sex relationships are offered in line with [Dunedin] Diocesan Policy and with the bishop's permission."[207] In the Diocese of Auckland, a couple was "joined in a civil union at the inner-Auckland Anglican church of St Matthews in the City in 2005."[208]

- Anglican Church of Australia: The church does not have an official position on homosexuality.[209] In 2013, the Diocese of Perth voted to recognise same-sex relationships.[210] The Social Responsibilities Committee of the Anglican Church Southern Queensland supported "the ability for same-sex couples to have a legally recognised ceremony to mark their union."[211] The Diocese of Gippsland has appointed clergy in a "same-sex partnership."[212] St. Andrew's Church in Subiaco, in Perth, has publicly blessed a same-sex union.[213]

- Anglican Church of Canada: In 2016, the Anglican Church of Canada voted to permit same-sex marriage after a vote recount.[214] The motion must pass a second reading in 2019 to become church law.[215] The dioceses of Niagara and Ottawa announced that same-sex marriages could begin in their churches immediately.[216][217] Several other dioceses allow same-sex blessing ceremonies.[218]

- Anglican Church of Southern Africa: Clergy are not permitted to enter in same-sex marriages or civil unions, but the church "tolerates same-sex relationships if they are celibate."[219] Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, the current Anglican Primate, is "one among few church leaders in Africa to support same-sex marriage..."[220] The Diocese of Saldanha Bay has proposed a blessing for same-sex unions.[221]

- Church in Wales: Clergy are allowed to enter into same-sex civil partnerships, and there is no requirement of sexual abstinence.[222] In 2015, a majority of the General Synod of the Church in Wales voted for same-sex marriage.[223] Also, the "Church has published prayers that may be said with a couple following the celebration of a civil partnership or civil marriage."[224]

- Church of England: Since 2005, clergy are permitted to enter into same-sex civil partnerships, but are requested to give assurances of following the Bishops' guidelines on human sexuality.[225] In 2013, the House of Bishops announced that priests in same-sex civil unions may serve as bishops.[226] As for ceremonies in church, "clergy in the Church of England are permitted to offer prayers of support on a pastoral basis for people in same-sex relationships;[227] many priests already bless same-sex unions on an unofficial basis.[228] Some congregations may offer "prayers for a same-sex commitment" or may "offer services of thanksgiving following a civil marriage ceremony."[229][230]

- Church of Ireland: In 2008, the Church of Ireland Pensions Board confirmed that it would treat civil partners the same as spouses.[231] In 2011, a minister of the Church of Ireland publicly entered into a same-sex civil partnership.[232]

- Episcopal Church (United States): At its 2015 triennial General Convention, the Episcopal Church voted overwhelmingly to allow religious weddings for same-sex couples. Many dioceses had previously allowed their priests to officiate at civil same-sex marriage ceremonies, but the church had not yet changed its own laws on marriage. The church law replaced the terms "husband" and "wife" with "the couple". Individual members of the clergy may still decline to perform same-sex weddings[233] Previously, the Episcopal Church had voted to allow a "generous pastoral response" for couples in same-sex civil unions, domestic partnerships, and marriages.[234]

- Scottish Episcopal Church: Since 2008, St. Mary's Cathedral in Glasgow has offered blessing services for same-sex civil partnerships.[235] The Scottish Episcopal Church agreed to bless same-sex marriages in 2015.[236] In 2016, the General Synod voted to amend the marriage canon to include same-sex couples.[237] The proposal was approved in a second reading in 2017, and same-sex marriages may be legally performed in the Scottish Episcopal Church.[238]

- Baptists (See: Homosexuality and Baptist churches): Because some Baptist churches operate on a congregational level, some individual churches may recognize same-sex unions. Baptist churches which recognize same-sex unions include:

- Latter Day Saint movement

- Community of Christ: In 2013, the Community of Christ officially decided to extend the sacrament of marriage to same-sex couples where gay marriage is legal, to provide covenant commitment ceremonies where it is not legal, and to allow the ordination of people in same-sex relationships to the priesthood. However, this is only in the United States, Canada, and Australia. The church does have a presence in countries where homosexuality is punishable by law, even death, so for the protection of the members in those nations, full inclusion of LGBT individuals is limited to the countries where this is not the case. Individual viewpoints do vary, and some congregations may be more welcoming than others. Furthermore, the church has proponents for support of both traditional marriage and same-sex marriages. The First Presidency and the Council of Twelve will need to approve policy revisions recommended by the USA National Conference.[241][242]

- Lutheranism (See Homosexuality and Lutheranism):

- Church of Norway: In 2013, the bishops announced that they would allow "gay couples to receive church blessings for their civil unions..."[243] In 2017, the Church of Norway decided to allow same-sex marriages to be performed in churches.[244]

- Church of Sweden: On 22 October 2009, the governing board of the Church of Sweden voted 176–62[245] in favour of allowing its priests to wed same-sex couples in new gender-neutral church ceremonies, including the use of the term marriage.[181][246] Same-sex marriages in the church will be available starting 1 November 2009.[247]

- Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD): The EKD is a federation of twenty Protestant churches in Germany. The blessing of same-sex unions is allowed in 18 of the 20 constituent member churches.[248][249]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America: During its 2009 Churchwide Assembly the ELCA passed a resolution by a vote of 619–402 reading "Resolved, that the ELCA commit itself to finding ways to allow congregations that choose to do so to recognize, support and hold publicly accountable lifelong, monogamous, same-gender relationships."[250]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark: In 2012, the Danish parliament voted to make same-sex marriages mandatory in all state churches. Individual priests may refuse to perform the ceremony, but the local bishop must organize a replacement.[251]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland: The church does not currently allow same-sex marriages to be legally officiated in churches. However, couples may enter in a civil partnership and "the couple may organise prayers with a priest or other church workers and invited guests. This may take place on church premises – but practice varies from parish to parish."[252] After a civil same-sex marriage, couples may request the same prayers in church. "All of the bishops have taken the position that it is possible to hold prayer services to bless same-sex couples."[253]

- Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches: This is a group of 26 member churches. Several of its member churches permit prayer services and blessings of same-sex civil unions.[254][255]

- Protestant Church in the Netherlands: The church has allowed the blessing of same-sex unions since 2001.[256] This has included the blessing of same-sex unions as well as marriages.[257]

- The United Protestant Church of France authorised the blessing of same-sex unions by pastors in May 2015, two years after the government legalized same-sex marriages. Individual vicars may refuse to perform same-sex marriage ceremonies.[citation needed]

- The Metropolitan Community Church perform same-sex marriages. The MCC was founded to support LGBT Christians. In 1968, MCC founder Rev. Troy Perry officiated the first public same-sex marriage ceremony in the United States, though it was not legally recognized at the time.[258][259]

- Methodism

- Methodist Church of Great Britain: In 2021 The Methodist Conference voted to allow same sex marriages to be performed in Methodist Churches. The resolutions enabled churches to equalise the treatment of marriages irrespective of the gender(s) of the couple.

- In 2005, the Methodist Church voted to bless same-sex unions;[260] while the word 'blessing' was not ultimately used, the Methodist Church did confirm that, for same-sex unions, "prayers of thanksgiving or celebration may be said, and there may be informal services of thanksgiving or celebration."[261] Clergy are allowed to enter into same-sex civil partnerships or marriages.[262]

- Methodist Church of New Zealand: Clergy may enter into same-sex unions.[263]

- Methodist Church of Southern Africa: In Southern Africa, the Methodist Church has allowed clergy in same-sex relationships, but they are not permitted to be in a same-sex marriage. The Methodist "Church allowed [clergy] to be in a homosexual relationship whilst being a minister, and allowed [clergy] to stay in the Church's manse with [their] partner, but drew the line at recognising [their] same-sex marriage."[264] "The Methodist Church 'tolerates homosexuals' and even accepts same-sex relationships (as long as such relationships are not solemnised by marriage)..."[265]

- Old Catholic Church: A group of churches which separated from Roman Catholicism over the issue of papal authority.

- Many American Old Catholic churches perform same-sex marriage ceremonies.[266]

- The Union of Utrecht of the Old Catholic Churches is a federation of six European Old Catholic organizations, four of which allow same-sex marriage ceremonies.[citation needed]

- Presbyterianism (See Homosexuality and Presbyterianism):

- Church of Scotland: In 2015, the Kirk voted to allow congregations to ordain clergy who enter into same-sex civil partnerships.[267] The General Assembly voted to allow clergy in same-sex marriages in 2016.[268] Then, the General Assembly approved a report requesting churches to be able to perform same-sex marriages in church.[269]

- The Presbyterian Church (USA), the largest Presbyterian group in the United States, voted to allow same-gender marriages on 19 June 2014. This vote allows pastors to perform marriages in jurisdictions where same-sex marriages are legally recognized. Additionally, the Assembly voted to send out a proposed amendment to the Book of Order, changing the description of marriage from "between a man and a woman" to "between two people, traditionally between a man and a woman." This amendment needed to be approved by a majority of the 172 Presbyteries to take effect.[270] On 17 March 2015, the New Jersey–based Presbytery of the Palisade became the 87th presbytery to approve the ratification, making the change official.[271]

- Quakerism (See Homosexuality and Quakerism)

- The Canadian Yearly Meeting supports the right of same-sex couples to marry.[citation needed]

- Several American Quaker groups bless same-sex marriages.[citation needed]

- Roman Catholic Church: On 18 December 2023, in response to a formal request for clarity on matters of church doctrine, the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith issued a declaration called Fiducia supplicans.[272] While reaffirming that only opposite-sex couples may receive the sacrament of marriage, it affirms that priests and deacons may bless same-sex couples pastorally (whether civilly married or not), as well as unmarried opposite-sex couples and civilly married couples in which at least one party had been divorced.[272] The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) issued a statement saying the declaration made "a distinction between liturgical (sacramental) blessings[] and pastoral blessings".[273]

- United Church of Canada: The General Council of the church accepts same-sex marriages. However, each individual congregation is free to develop its own marriage policies.[274]

- United Church of Christ: In 2005, the General Synod adopted a resolution supporting equal access to marriage for all couples, regardless of gender. This resolution encouraged (but did not require) individual congregations to adopt policies supporting equal marriage rights for same-sex couples.[275]

- Conservative Judaism: In 2012, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards approved two model wedding ceremonies which can be adapted for the needs of same-sex couples. In 2013, the Rabbinical Assembly noted that they recognize both same-sex and opposite-sex marriages. However, individual synagogues are not required to adopt these policies, and may not perform marriages for same-sex couples.[276]

- Reconstructionist Judaism: Of the four leading Jewish denominations, Reconstructionist Judaism is often considered the most welcoming of LGBT people. In 2004, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association approved a resolution supporting civil marriage rights for same-sex couples.[277]

- Reform Judaism: Reform Judaism is the largest Jewish denomination in the United States, and is generally welcoming to LGBT people. In 1996, the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR) announced its support for civil same-sex marriage rights. This was followed by a similar resolution from the Union for Reform Judaism in 1997. In 2000, the CCAR gave its full support to rabbis who officiate same-sex weddings. This resolution also recognizes that some Reform rabbis will not officiate same-sex weddings.[278]

Other

[edit]- Afro-Brazilian religions: These faiths may support same-sex marriages, but this is up to individual interpretation. They historically tend to have been openly LGBT-positive even among variants heavily influenced by Christianity and Allan Kardec's Spiritism.[279]

- Buddhism (See Buddhism and sexual orientation): Because Buddhism has no central authority, there is no general consensus on same-sex marriage within Buddhism.[282] The world's first Buddhist same-sex marriage was performed at a San Francisco Jodo Shinshu temple in the 1970s, and the introduction of same-sex marriages in the Buddhist Churches of America was not controversial.[283] Same-sex marriages are performed at Shunkō-in, a Rinzai Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan.[284] American Soka Gakkai Buddhists have performed same-sex union ceremonies since the 1990s.[285]