The Embroidered Couch

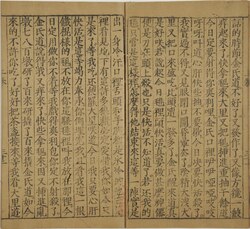

The title page from the first volume of a Ming dynasty edition (collection of Yamaguchi University) | |

| Author | Lü Tiancheng (呂天成) |

|---|---|

| Original title | 繡榻野史 |

| Translator | Lenny Hu |

| Language | Chinese |

Publication date | c. 1600 |

| Publication place | China (Ming dynasty) |

Published in English | 2001 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 237 |

| The Embroidered Couch | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 繡榻野史 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 绣榻野史 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Xiuta yeshi, translated into English as The Embroidered Couch,[a] is a Chinese erotic novel composed during the late Ming dynasty by playwright Lü Tiancheng (呂天成) under various pseudonyms. Believed to be one of the oldest Chinese erotic novels, Xiuta yeshi was first published at around the same time as Jin Ping Mei (The Golden Lotus). It has been constantly banned or censored since then, especially during the Qing dynasty. Literary critics have drawn attention to its obscenity and vivid descriptions of sex. A complete English translation by Lenny Hu was published in 2001.

Plot

[edit]The male protagonist of Xiuta yeshi, which begins in the year 1594,[8] is thirty-year-old xiucai Yao Tongxin (姚同心),[9][10] also known as Dongmen sheng (東門生; Scholar of the Eastern Gate),[11] presumably a reference to his birthplace (a part of Yangzhou known as "East Gate").[10] Having led a debauched lifestyle in his younger days, he now has a relatively poor stamina,[11] and is hence unable to sexually satisfy his wife, Jinshi (金氏) or Madame Jin.[10] After receiving much ridicule from others and being unable to improve the situation with medication, he arranges for his wife to have sex with his bisexual lover Zhao Dali (趙大里) instead.[10]

Zhao fails to satisfy Jinshi during their first tryst; he returns the following night with aphrodisiacs.[9] Jinshi then sustains a vaginal tear and rectal prolapse[12] in what becomes a wild orgy involving herself, Zhao, and two servant girls.[9] Afterward, Jinshi arranges for Zhao's widowed mother, Mashi (麻氏), to live with Dongmen and herself when Zhao goes for a business trip.[9] While intoxicated, Mashi is enticed by Jinshi into having sex with Dongmen, who is passing off as Jinshi's cousin; Mashi, Dongmen, and Jinshi soon find themselves in a ménage à trois. However, Jinshi later becomes jealous of the older woman, just as Zhao returns. Although the four of them agree to live under one roof, they take to the mountains after their neighbours learn about their polyamory.[9]

Dongmen fathers two sons with Mashi, but she dies within three years; Jinshi and Zhao also die soon after due to complications arising from sex. Having dreamt that his three deceased lovers have been reincarnated as animals, Dongmen entrusts his children to his maid Xiao Jiao (小嬌) and becomes a Buddhist monk.[9]

Authorship and publication history

[edit]Xiuta yeshi was composed in vernacular Chinese (with the influence of Wu Chinese as the story is set in Yangzhou)[13] during the late Ming dynasty in 1597[7] by playwright Lü Tiancheng (呂天成) under various pseudonyms like "Qingdian zhuren" (情癲主人; "Master of crazy passion") and "Zuimiange hanhanzi"(醉眠閣憨憨子; "The silly literati at the drunken slumber gazebo")[14] at around the same time Tang Xianzu finished The Peony Pavilion.[15] At the time of writing, Lü was still a teenager.[8] The original manuscript has 237 pages divided into four juan (卷) or chapters.[16] In the preface to the novel, Lü writes an "apology": "I want to stop the whole world from sexual excess, but as it is already too far gone in that direction, nobody will listen to my advice. If I show them what result may come out of it, and lead them gradually on in the right direction, people can be saved."[17]

Xiuta yeshi was published in around 1600, at about the same time as Jin Ping Mei (The Golden Lotus).[18] For centuries after its publication, during the Qing dynasty, Xiuta yeshi was constantly included in the lists of jinshu (禁書) or forbidden books by central and local bureaucrats. At the same time, it "remained in circulation, albeit surreptitiously under severe censorship, and was sought after by private collectors as well as various libraries, including those in Japan."[19] Reportedly "the first English translation of an erotic novel published in China in the 17th century", The Embroidered Couch: An Erotic Novel of China by Lenny Hu was published by Arsenal Pulp Press in late 2001.[20][21]

Literary significance

[edit]

Xiuta yeshi is a "realist erotic novel", similar to Jin Ping Mei (The Golden Lotus) which was also published in the late Ming dynasty;[22] according to Wilt L. Idema, Xiuta yeshi is "most likely China's earliest vernacular pornographic novel",[15] while Ka F. Wong notes that it is "supposedly preceded only by Jin Ping Mei and Langshi (浪史) ... although the chronology of these three works is debatable".[9] According to Wong, Xiuta yeshi "is destined to be compared with Jin Ping Mei", although he finds it an unfair comparison insofar as the latter novel is primarily a socio-satirical work, with its sex scenes being a minor part of the plot.[23] On the other hand, Xiuta yeshi "does not seem to take itself too seriously" and "takes some pleasure in mocking" Jin Ping Mei; for instance, the male protagonist of Xiuta yeshi, Dongmen sheng, is a "reverse image"—in terms of genital size and sexual stamina—of the "incorrigible womaniser" in Jin Ping Mei, Ximen Qing.[11]

Wong also argues that as "a sexual icon in its own right, Xiuta yeshi is often used as shorthand for ars erotica and has had its storyline duplicated."[11] The short story "Jiang Xingge chonghui zhenzhushan" (蔣興哥重會珍珠衫) or "Jiang Xingge reencounters his pearl-sewn shirt" by Feng Menglong contains a scene reminiscent of Jinshi's seduction of Mashi.[24] Alongside Ruyi Jun zhuan (如意君傳; The Lord of Perfect Satisfaction) and Chipozi zhuan (癡婆子傳; The Story of the Foolish Woman), Xiuta yeshi is one of the three erotic novels referenced in The Carnal Prayer Mat believed to have been written by Qing dynasty writer Li Yu.[3] The mid-eighteenth century erotic novel Yi Qing zhen (怡情陣; Battle for Cheering Passion) is "basically a copy" of Xiuta yeshi.[24]

Critical reception

[edit]Since its release, Xiuta yeshi has been the subject of disrepute. Writing in the preface of a 1608 edition of Xiuta yeshi, Wuling Haochang (五陵豪長) censures the book as a "biography of obscenity".[16] The early Qing dynasty commentator Liu Tingji (劉廷璣) attacks the novel as "poison" ("inexhaustibly poisonous"),[25][16] while Zhang Yu (張譽), writing half a decade earlier, compares it to "dirty old men and crude prostitutes".[16]

Likewise, modern commentary has often focused on the novel's obscenity.[19] Yiheng Zhao describes the book as one of the "dirtiest late Ming novels extant"[17] while Bret Hinsch writes that it is "lurid pornography" and "extravagantly grotesque".[7] Unfavourably comparing it to "higher-class" works like The Golden Lotus and The Carnal Praying Mat, John Minford dismisses Xiuta yeshi as a "crude" novel.[26] Giovanni Vitiello calls it a "novel representative of the genre where the plot serves only as frame-work for a series of obscene descriptions."[27] Similarly, Jie Guo argues that in the novel, "priority is often given to sex, rather than to plot or characterization", although he acknowledges that the sexual episodes in Xiuta yeshi link to one another to create a coherent narrative.[28] Describing the novel as "a highly creative work", Ka F. Wong highlights the originality of the plot as well as the author's depiction of sex "in every credible and incredible way".[9] Translator Lenny Hu found Xiuta yeshi to be "a very funny book" and "became fond of the characters".[21]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Vitiello 1994, p. 21.

- ^ Wu & Stevenson 2011, p. 474.

- ^ a b Hanan 1988, p. 123.

- ^ Mair 2010, p. 665.

- ^ Fang 2013, p. 87.

- ^ Yao 2018, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Hinsch 2021, p. 86.

- ^ a b Wong 2007, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wong 2007, p. 293.

- ^ a b c d Huang 2020, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d Wong 2007, p. 295.

- ^ Wong 2007, p. 314.

- ^ Wong 2007, p. 294.

- ^ Wong 2007, p. 291.

- ^ a b Idema 2003, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Wong 2007, p. 285.

- ^ a b Zhao 2020, p. 91.

- ^ McMahon 1987, p. 223.

- ^ a b Wong 2007, p. 286.

- ^ Lü 2013, p. 1.

- ^ a b Conlogue, Ray (20 October 2001). "Rough translation: very rude". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Vitiello 1994, p. 36.

- ^ Wong 2007, p. 325.

- ^ a b Wong 2007, p. 296.

- ^ 流毒無盡

- ^ Minford 2006, p. xvii.

- ^ Vitiello 1994, p. 35.

- ^ Guo 2010, p. 249.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fang, Fu Ruan (2013). Sex in China: Studies in Sexology in Chinese Culture. Perspectives in Sexuality. Springer Science & Business Media. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0609-0. ISBN 9781489906090.

- Guo, Jie (2010). "Robert Hans van Gulik Reading Late Ming Erotica" (PDF). Hanxue Yanjiu (Chinese Studies). 28 (2): 225–265. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-06-06. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- Hanan, Patrick (1988). The Invention of Li Yu. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674464254.

- Hinsch, Bret (2021). Women in Ming China. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781538152973.

- Huang, Martin W. (2020). Desire and Fictional Narrative in Late Imperial China. Brill. doi:10.1163/9781684173570. ISBN 9781684173570.

- Idema, Wilt L. (2003). ""What Eyes May Light upon My Sleeping Form?": Tang Xianzu's Transformation of His Sources, with a Translation of "Du Liniang Craves Sex and Returns to Life"". Asia Major. 16 (1). Academia Sinica: 111–145. JSTOR 41649872.

- Lü, Tiancheng (2013) [First published c. 1600]. Xiùtà Yěshǐ 繡榻野史 [The Embroidered Couch: An Erotic Novel of China]. Translated by Hu, Lenny. Arsenal Pulp Press. ISBN 9781551525310.

- Mair, Victor H. (2010). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231528511.

- McMahon, Keith (1987). "Eroticism in Late Ming, Early Qing Fiction: The Beauteous Realm and the Sexual Battlefield". T'oung Pao. 73 (4): 217–264. doi:10.1163/156853287X00032. JSTOR 4528390. PMID 11618220.

- Minford, John (2006). Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140447408.

- Vitiello, Giovanni (1994). Exemplary Sodomites: Male Homosexuality in Late Ming Fiction. University of California Press. OCLC 34155026.

- Wong, Ka F. (2007). "The Anatomy of Eroticism: Reimagining Sex and Sexuality in the Late Ming Novel". Nan Nü. 9 (2): 284–329. doi:10.1163/138768007X244361.

- Wu, Cuncun; Stevenson, Mark (2011). "Karmic Retribution and Moral Didacticism in Erotic Fiction from the Late Ming and Early Qing". In Santangelo, Paolo (ed.). Ming Qing Studies 2011. Aracne Editrice. pp. 471–490. hdl:1959.11/16123. ISBN 9788854844636.

- Yao, Ping (2018). "Between Topics and Sources: Researching the History of Sexuality in Imperial China". In Chiang, Howard (ed.). Sexuality in China: Histories of Power and Pleasure. University of Washington Press. pp. 34–49. ISBN 9780295743486.

- Zhao, Yiheng (2020). The River Fans Out: Literature and its Theories in China. China Academic Library. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-7724-6. ISBN 9789811577246. S2CID 226449538.