Great tinamou

| Great tinamou | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Order: | Tinamiformes |

| Family: | Tinamidae |

| Genus: | Tinamus |

| Species: | T. major |

| Binomial name | |

| Tinamus major (Gmelin, JF, 1789) | |

| Subspecies[2] | |

| See text | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

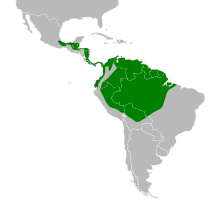

The great tinamou (Tinamus major) is a species of tinamou ground bird native to Central and South America. There are several subspecies, mostly differentiated by their coloration.

Taxonomy

[edit]The great tinamou was described and illustrated in 1648 by the German naturalist Georg Marcgrave in his Historia Naturalis Brasiliae. Marcgrave used the name Macucagua.[4] The French polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon described and illustrated the great tinamou in 1778 in his Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux from specimens collected in Cayenne, French Guiana. He simplified Marcgrave's name to Magoua.[5] When in 1788 the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin revised and expanded Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae, he included the great tinamou and placed it with all the grouse like birds in the genus Tetrao. He coined the binomial name Tetrao major and cited the earlier authors.[6] The great tinamou is now placed with four other species in the genus Tinamus that was introduced in 1783 by the French naturalist Johann Hermann.[7][8] Hermann based his name on "Les Tinamous" used by Buffon. The word "Tinamú" in the Carib language of French Guiana was used for the tinamous.[9][10]

All tinamous are from the family Tinamidae, and are the closest living relatives of the ratites. Unlike ratites, tinamous can fly, although in general, they are not strong fliers. All ratites evolved from prehistoric flying birds.[11]

Twelve subspecies are recognised:[8]

- T. m. robustus Sclater, PL & Salvin, 1868 – southeast Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras

- T. m. percautus Van Tyne, 1935 – south Mexico, north Guatemala and Belize

- T. m. fuscipennis Salvadori, 1895 – north Nicaragua to west Panama

- T. m. brunneiventris Aldrich, 1937 – south-central Panama

- T. m. castaneiceps Salvadori, 1895 – southwest Costa Rica and west Panama

- T. m. saturatus Griscom, 1929 – east Panama and northwest Colombia

- T. m. zuliensis Osgood & Conover, 1922 – northeast Colombia and north Venezuela

- T. m. latifrons Salvadori, 1895 – southwest Colombia and west Ecuador

- T. m. major (Gmelin, JF, 1789) – east Venezuela to northeast Brazil

- T. m. serratus (Spix, 1825) – northwest Brazil

- T. m. olivascens Conover, 1937 – Amazonian Brazil

- T. m. peruvianus Bonaparte, 1856 – southeast Colombia to Bolivia and west Brazil

Description

[edit]The great tinamou is a large species of tinamou, measuring in total length at approximately 38 to 46 cm (15 to 18 in), with a mean of 44 cm (17 in), and weighing from 700 to 1,142 g (1.543 to 2.518 lb) in males, with a mean of 960 g (2.12 lb), and from 945 to 1,249 g (2.083 to 2.754 lb) in females, with a mean of 1,097 g (2.418 lb). Despite its name and large size and shape, which may be suggestive of a large pheasant or a small turkey, it is not necessarily the largest species of tinamou, as it is rivaled or exceeded by other species in the Tinamus. It ranges from light to dark olive-green in color with a whitish throat and belly,[11][12][13][14] flanks barred black, and undertail cinnamon. Crown and neck rufous, occipital crest and supercilium blackish. Its legs are blue-grey in color. All these features enable great tinamou to be well-camouflaged in the rainforest understory.

The great tinamou has a distinctive call, three short, tremulous but powerful piping notes which can be heard in its rainforest habitat in the early evenings.[11]

The great tinamous has the highest percentage of skeletal muscle devoted to locomotion among all birds, with 56.9% of its total body weight (43.74% of its body weight is skeletal muscle devoted to flight), at the same time, its heart is the smallest of all birds, in relative comparison (0.19%).[15][16]

Habitat

[edit]Great tinamou lives in subtropical and tropical forest such as rainforest, lowland evergreen forest, river-edge forest,[3] swamp forest and cloud forest at altitudes from 300 to 1,500 m (1,000–4,900 ft). Unlike some other tinamous, the great tinamou isn't as affected by forest fragmentation.[1] Its nest can be found at the base of a tree.

Breeding

[edit]

The great tinamou is a polygynandrous species, and one that features exclusive male parental care. A female will mate with a male and lay an average of four eggs which he then incubates until hatching. He cares for the chicks for approximately 3 weeks before moving on to find another female. Meanwhile, the female has left clutches of eggs with other males. She may start nests with five or six males during each breeding season, leaving all parental care to the males. The breeding season is long, lasting from mid-winter to late summer. The eggs are large, shiny, and bright blue or violet in color, and the nests are usually rudimentary scrapings in the buttress roots of trees.[11]

Except during mating, when a pair stay together until the eggs are laid, great tinamous are solitary and roam the dark understory alone, seeking seeds, fruit, and small animals such as insects, spiders, frogs and small lizards in the leaf litter. They are especially fond of Lauraceae, annonaceae, myrtaceae, sapotaceae.[11]

Conservation

[edit]This species is widespread throughout its large range (6,600,000 km2 (2,500,000 sq mi)),[17] and it is evaluated as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1] They are hunted with no major effect on their population.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2021). "Tinamus major". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22678148A189781191. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Brands, S. (2008)

- ^ a b American Ornithologists' Union (1998)

- ^ Marcgrave, Georg (1648). Historia Naturalis Brasiliae: Liber Quintus: Qui agit de Avibus (in Latin). Lugdun and Batavorum (London and Leiden): Franciscum Hackium and Elzevirium. p. 213.

- ^ Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de (1778). "Le Magoua". Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: De l'Imprimerie Royale. pp. 507–510, Plate 24.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. pp. 767–768, No. 63.

- ^ Hermann, Johann (1783). Tabula affinitatum animalium olim academico specimine edita, nunc uberiore commentario illustrata cum annotationibus ad historiam naturalem animalium augendam facientibus. Argentorati [Strasbourg]: Impensis Joh. Georgii Treuttel. pp. 164, 235.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2022). "Ratites: Ostriches to tinamous". IOC World Bird List Version 12.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de (1778). "Le tinamou cendré". Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: De l'Imprimerie Royale. p. 502.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 386. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- ^ Cabot, J., F. Jutglar, E. F. J. Garcia, P. F. D. Boesman, and C.J. Sharpe (2020). Great Tinamou (Tinamus major), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- ^ Schulenberg, T. S., Stotz, D. F., Lane, D. F., O'Neill, J. P., & Parker III, T. A. (2010). Birds of Peru: Revised and Updated Edition. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Dunning Jr, J. B. (2007). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press.

- ^ Calder, William A. (1996). Size, Function, and Life History. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-69191-6.

- ^ Hartman, F. A. (1961). "Locomotor mechanisms of birds". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections.

- ^ BirdLife International (2008)

Sources

[edit]- American Ornithologists' Union (1998) [1983]. "Tinamiformes: Tinamidae: Tinamous". Check-list of North American Birds (PDF) (7th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union. p. 1. ISBN 1-891276-00-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- BirdLife International (2008). "Great Tinamou - BirdLife Species Factsheet". Data Zone. Retrieved 6 Feb 2009.

- Brands, Sheila (Aug 14, 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Tinamus major". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Feb 4, 2009.

- Brennan, P. T. R. (2004). Techniques for studying the behavioral ecology of forest-dwelling tinamous (Tinamidae). Ornitologia Neotropical 15(Suppl.) 329–337.

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003). "Tinamous". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 57–59, 61–62. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- Stiles, & Skutch, A guide to the birds of Costa Rica ISBN 0-8014-9600-4

External links

[edit]- Great Tinamou videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- BirdLife Species Factsheet

- Stamps[usurped] (for Honduras, Panama) with RangeMap

- Great Tinamou photo gallery VIREO