USS Sterlet

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

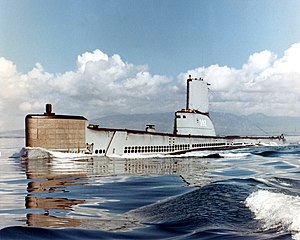

USS Sterlet (SS-392) in 1968 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Builder | Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Kittery, Maine[1] |

| Laid down | 14 July 1943[1] |

| Launched | 27 October 1943[1] |

| Commissioned | 4 March 1944[1] |

| Decommissioned | 18 September 1948[1] |

| Recommissioned | 26 August 1950[1] |

| Decommissioned | 30 September 1968[1] |

| Stricken | 1 October 1968[1] |

| Fate | Sunk as a target, 31 January 1969[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Balao class diesel-electric submarine[2] |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 311 ft 6 in (94.95 m)[2] |

| Beam | 27 ft 3 in (8.31 m)[2] |

| Draft | 16 ft 10 in (5.13 m) maximum[2] |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | |

| Range | 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) surfaced at 10 knots (19 km/h)[6] |

| Endurance |

|

| Test depth | 400 ft (120 m)[6] |

| Complement | 10 officers, 70–71 enlisted[6] |

| Armament |

|

USS Sterlet (SS-392), a Balao-class submarine, was the only ship of the United States Navy to be named for the sterlet, a small sturgeon found in the Caspian Sea and its rivers, whose meat is considered delicious and whose eggs are one of the world's great delicacies, caviar.

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Sterlet′s keel was laid down on 14 July 1943 at the Portsmouth Navy Yard in Kittery, Maine. She was launched on 27 October 1943 in the first triple launching in the history of submarine construction.[7] Sterlet and USS Pomfret (SS-391) were christened in the building basin and USS Piranha (SS-389) was christened and launched from the building ways. Sterlet was sponsored by Mrs. Charles A. Plumley and was commissioned on 4 March 1944.

Service history

[edit]Following fitting-out and shakedown training, Sterlet departed Key West, Florida, on 1 May 1944 to join the United States Pacific Fleet. The submarine reached Pearl Harbor on 13 June 1944, and she immediately plunged into another round of training exercises to prepare for her first war patrol.

First war patrol

[edit]On 4 July 1944, she put to sea to prey on Japanese shipping. The patrol lasted 53 days; and Sterlet spent 34 of them in her assigned patrol area, the Bonin Islands. On 8 August 1944, she torpedoed and sank the minesweeper Tama Maru No. 6.[8][9] By the time she put into Midway Island for refit on 26 August, the submarine was a battle-proven veteran, claiming to have sunk four enemy ships. She even brought in a prisoner — a survivor from a Japanese convoy destroyed by American aircraft carrier planes three weeks earlier.

Second war patrol

[edit]The submarine remained at Midway for just over three weeks; then headed for its patrol area in the Nansei Shoto on 18 September. After sinking a small Japanese fishing boat on 9 October, Sterlet rescued six downed airmen off Okinawa. On 18 October, she made an unsuccessful attempt to close and attack one of six destroyers escorting three cruisers. Two days later, she fired a spread of three torpedoes at a Japanese cargo ship, but all three missed. She made a third fruitless approach on 25 October, firing four torpedoes on small convoy. Results: four misses.

Not to be denied, Sterlet made another approach on the convoy. This time, four of the six torpedoes she launched scored. Three hit a large gasoline tanker, and the fourth impacted a freighter. The tanker, Jinei Maru, is known definitely to have gone down. Sterlet spent the remainder of the day evading the attacks of the escorts. That night, she allowed a hospital ship to pass unmolested. She attacked a small freighter with four torpedoes on 29 October, but had to surface and sink it with her deck gun. On 31 October, she made a night surface attack on a tanker previously damaged by Trigger (SS-237) and apparently sank it with a spread of six torpedoes. Sterlet then joined Trigger in escorting the damaged Salmon (SS-182) into Saipan.

From there, Sterlet put to sea on 10 November with six other submarines in a coordinated attack group. On the night of 15 November, she, Trigger, and Silversides (SS-236) engaged in a gun duel with an enemy sub chaser. Sterlet completely depleted her supply of five-inch (127 mm) shells in the battle and was forced to sink the enemy craft with torpedoes early the following morning. On 30 November, the submarine returned to the Submarine Base at Pearl Harbor.

Third war patrol

[edit]Following almost two months in Hawaii, Sterlet embarked on her third war patrol on 25 January 1945. Her assigned area was off Honshū, Japan, particularly the area off Tokyo Bay, where she stood lifeguard duty for Fifth Fleet pilots attacking Tokyo. She made reconnaissance sweeps of the Japanese Fleet and patrolled with a "wolfpack" that also included Piper (SS-409), Pomfret (SS-391), Bowfin (SS-287), and Trepang (SS-412). During this cruise, she made two torpedo attacks, one each on 1 March and 5 March, and claimed two sinkings, a freighter and a tanker. (Japanese sources list Imperial Japanese Army transport ship Tateyama Maru as being sunk by a torpedo strike from the Sterlet on 1 March).[10] She ended the war patrol at Midway on 4 April.

Fourth War Patrol

[edit]Sterlet’s fourth war patrol lasted from 29 April to 10 June and took her north of Japan to the Sea of Okhotsk and the vicinity of the Kuril Islands. On this cruise, her proximity to Soviet territory and the port of Vladivostok complicated her mission. Though Soviet ships were advised to remain out of the war zone around Japan, Sterlet had to be extremely vigilant in her identification of potential targets lest she inadvertently attack an ally. Lack of certainty in identification forced the submarine to pass up several targets. To further cloud the issue, Japanese ships probably attempted to disguise themselves as Soviets on several occasions to escape American submarines.

Sterlet, however, managed to emerge victorious over two enemy ships. In the late afternoon of 29 May, she encountered a large and a small freighter, escorted by three patrol frigates. At 16:41, the submarine tried for a good setup, but failed due to the convoy's rapid change in course. She lost sound contact around 1720 and, 40 minutes later, surfaced for a daylight end-around. At 1822, the lookouts sighted smoke; by 21:53, the submarine was in position to launch a night surface radar attack. She launched six torpedoes, three at each freighter. Two minutes later, one of the escorts peeled off and made for Sterlet. She immediately went right full rudder, all ahead at flank speed. In another two minutes, two torpedoes impacted each of the two targets—four explosions within 20 seconds. At 22:05, the enemy frigate began random depth charge attacks. Three minutes later, the smaller of the two targets sank by the stern.

At 22:11, Sterlet unleashed four torpedoes at the pursuing escort. The setup was hasty at best. All four missed, and she prudently opened range to reload and prepare for another attack on the damaged freighter still afloat. As she approached, her quarry was dead in the water, down by the stern, and partially enveloped by smoke. Two of the escorts were thrashing about the surrounding waters, indiscriminately shooting and dropping depth charges. At 22:35, one of them passed between Sterlet and her victim. The submarine shifted her sights on him and, four minutes later, fired three torpedoes at him. The frigate sighted the wakes, immediately turned into them, and rapidly closed on Sterlet. This pursuit forced Sterlet to retire. After more than an hour of running from the frigate and undergoing his bombardment, she managed to open range by firing four torpedoes "down the throat" at him. This tactic did not allow her to escape, and the chase continued until the frigate turned broadside to fire both his forward and after guns in salvo. That curious maneuver allowed Sterlet to open range to 8,000 yards (7,300 m) at which point, the enemy's radar wavered. Sterlet shut her radar down, came hard to starboard and opened out. A minute before midnight, Sterlet turned her radar back on. The screen was clear; she had escaped.

The submarine had one more anxious moment during the patrol, when she encountered a Q-ship screened by a small escort. She launched six torpedoes at the "freighter," which disconcertingly turned and closed Sterlet. She evaded successfully and returned to Midway on 10 June.

Fifth war patrol

[edit]Sterlet’s final war patrol commenced on 5 July when she departed Midway for the vicinity of Kii Suido and Bungo Suido. Except for one occasion when she shelled oil storage tanks and a power plant near Shingu on Honshū, this whole patrol was given over to lifeguard duty for the crews of carrier planes and B-29 Superfortresses attacking Japan. Sterlet rescued a New Zealander and a Briton, one was near the Kii Channel between Shikoku and Honshu. When Japanese capitulation brought an end to the patrol, Sterlet returned to Midway on 23 August. On 6 September, she sailed for the United States reaching San Diego Naval Base ten days later.

Post-war activities

[edit]Sterlet remained on the West Coast until the end of February 1946, at San Diego until 13 November and at San Francisco, California, thereafter. On 26 February 1946, she started back to the western Pacific and after briefly stopping at Pearl Harbor, Guam, and Subic Bay, arrived in Tsingtao, China, on 20 April. She operated out of Tsingtao until the end of May, participating in the Navy's show of force along the northern China coast. She spent the first ten days of June in Shanghai and then got underway for Pearl.

Sterlet reached Oahu on 22 June and conducted operations in the Hawaiian Islands for the next 16 months. She headed west again on 15 November 1947 and reached Brisbane, Australia, on 1 December. Five days later, the submarine shaped a course for Guam, arriving there on 14 December. She departed Guam on 2 January 1948, stopped at Okinawa from 6 January to 10 January, and arrived in the Sasebo operating area on 12 January. For the rest of the month, she operated in the vicinity of Sasebo and Yokosuka, visiting both ports. On 28 January, she sailed for the California coast and, after a brief stop at Midway and a six-week layover in Pearl Harbor, reached San Francisco on 30 April. On 1 May, she reported to the Pacific Reserve Fleet for inactivation. She was placed out of commission, in reserve on 18 September 1948 and berthed at Mare Island, California.

Just under two years later, on 7 August 1950, Sterlet was ordered reactivated. She was recommissioned at Mare Island on 26 August 1950. On 25 September, she headed for San Diego where she conducted a month of training. In December, she shifted to Long Beach, California, where she became one of the stars in the motion picture Submarine Command with William Holden and William Bendix.[11]

Sterlet resumed operations along the West Coast early in 1951 and that employment continued until January 1953, when she was deployed to the Far East. On this cruise, she joined in hunter-killer exercises, visited Chichi Jima, Atami, Japan, and Buckner Bay, Okinawa; and conducted photographic reconnaissance on Marcus Island. She returned to San Diego, California, on 23 June and resumed West Coast operations.

In August 1954, Sterlet exchanged crews and homeports with Besugo (SS-321). On 13 September, she reported for duty to Submarine Squadron 1 at Pearl Harbor. For the remainder of her Navy career, Sterlet was home ported at Pearl Harbor. Between 1954 and 1968, she alternated operations in the Hawaiian Islands with nine deployments to the western Pacific with the Seventh Fleet. On these cruises, usually of approximately six months duration, she participated in a host of exercises and war game problems and visited most major ports in the Far East, particularly those in Japan, Taiwan, China and in some of the Central Pacific islands.

After her return from her final deployment in the summer of 1968, Sterlet was found to be unfit for further naval service. Accordingly, she was decommissioned on 30 September 1968, and her name was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on the following day. She rendered her last service to the Navy on 31 January 1969 when she was sunk as a target by the nuclear-powered submarine USS Sargo (SSN-583).

Honors and awards

[edit]Sterlet was awarded six battle stars for World War II service.

External links

[edit]- Sterlet SS-392 Undersea Warrior

- http://usssterlet.com/

- SS-392, USS STERLET Submarine War Patrol Report. United States Navy. 17 February 2009.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 285–304. ISBN 1-55750-263-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 275–280. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- ^ a b c d e Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 275–280. ISBN 978-0-313-26202-9.

- ^ U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 261–263

- ^ a b c U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 305–311

- ^ a b c d e f U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 305-311

- ^ ""First Triple Submarine Launching on Navy Day"". The Portsmouth Periscope. 2 (3): 8. 12 November 1943.

- ^ Toda, Gengoro S. "第六玉丸の船歴 (Tama Maru No. 6- Ship History)". Imperial Japanese Navy -Tokusetsu Kansen (in Japanese).

- ^ "8 Aug 1944 USS Sterlet (Lt.Cdr. O.C. Robbins) torpedoed and sank the Japanese auxiliary submarine chaser Tama Maru No.6 (275 GRT) west of Chichi Jima in position 28'11'N, 141'06'E". Uboat.net. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Toda, Gengoro S. "立山丸の船歴 (Tateyama Maru - Ship History)". Imperial Japanese Navy (in Japanese).

- ^ "Sterlet (SS-392)". NHHC. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.