Utagawa school

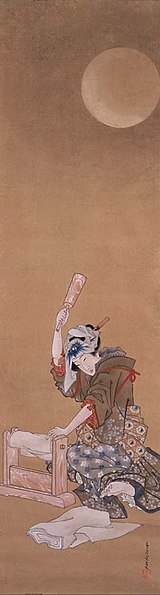

The Utagawa school (歌川派) was one of the main schools of ukiyo-e, founded by Utagawa Toyoharu. It was the largest ukiyo-e school of its period. The main styles were bijin-ga (beautiful women) and uki-e (perspective picture). His pupil, Toyokuni I, took over after Toyoharu's death and led the group to become the most famous and powerful woodblock print school for the remainder of the 19th century.

Hiroshige,[1] Kunisada, Kuniyoshi and Yoshitoshi were Utagawa students. The school became so successful and well known that today more than half of all surviving ukiyo-e prints are from it.

Founder Toyoharu adopted Western-style deep perspective, an innovation in Japanese art. His immediate followers, Utagawa Toyohiro and Toyokuni adopted bolder, more sensuous styles than Toyoharu and specialized in different genres — Toyohiro in landscapes and Toyokuni in kabuki actor prints. Later artists in the school specialized in other genres, such as warrior prints and mythic parodies.[2]

Utagawa school and inherited art-names

[edit]It was a Japanese custom for successful apprentices to take the names of their masters.[2] In the main Utagawa school, there was a hierarchy of gō (art-names), from the most senior to junior. As each senior person died, the others would move up a step.

The head of the school generally used the gō (and signed his prints) as Toyokuni. When Kunisada I proclaimed himself head of the school (c. 1842), he started signing as Toyokuni, and the next most senior member, Kochoro (a name also previously used by Kunisada I, but not as his chief gō), started signing as Kunisada (Kunisada II, in this case).

The next most senior member after him, in turn, began signing as Kunimasa (Kunimasa IV, in this case), which had been Kochoro's gō before he became Kunisada II. (The original Kunimasa I had been a student of Toyokuni I.)

Following is a list of some members of the main Utagawa school, giving the succession of names, along with the modern numbering of each:

- Toyokuni (I)

- Toyoshige -> Toyokuni (II)

- Kunisada (I) -> Toyokuni (III)

- Kochoro -> Kunimasa (III) -> Kunisada (II) -> Toyokuni (IV)

- Kochoro (II) -> Kunimasa (IV) -> Kunisada (III) -> Toyokuni (V)

See here for a more extensive list.

Two different Toyokuni IIs

[edit]An additional complexity is the fact that there are two different artists who are sometimes referred to as Toyokuni II; and similarly for the later-numbered artists called "Toyokuni".

The first Toyokuni II was Toyoshige, a mediocre pupil and son-in-law of Toyokuni I who became head of the Utagawa school after Toyokuni I died.

Kunisada I (Toyokuni III) apparently despised Toyoshige, and refused to acknowledge him as head of the Utagawa school. Apparently, this was because he felt that as the best pupil, he should have been named head after the old master died, and was upset with Toyoshige, who apparently got the position because of his family connection.

When Kunisada I took the art-name Toyokuni (c. 1842), he effectively removed Toyokuni II from house history and for a period actually signed as Toyokuni II. However, he is now numbered, Toyokuni III. There are prints which signed Toyokuni II which are by the artist now known as Toyokuni III.

This numbering persisted, so when Kochoro became head of the Utagawa school, he signed as Toyokuni III, although he would be the fourth Toyokuni. Likewise Kochoro II eventually signed as Toyokuni IV, and is now numbered Toyokuni V.

Family

[edit]According to the encyclopedia of Ukiyo-e in the late 1980s, the Utagawa school had 151 students, 147 workers from Kuniyoshi, and 173 people from Kuniyoshi. Students who studied at the Utagawa school would gain the chance to receive the Utagawa name if their skill is approved. The master would give out the Utagawa surname, and the use of “Toshinomaru”, which is Utagawa's own family crest that is only found within the Utagawa family to the best students. The “Yearball”, rounded design, was the symbol of the Utagawa family. This symbol was easy to recognize, so the people who wore the Utagawa crested kimono did not need the ticket to the Edo theater at that time.[3] The “Tatsunori no Maru” crest of the same shape with an added line, was used only by the master of Muneya and his workers. The next master was decided at a convention of the very large Utagawa Ichimon family. The master was mainly decided by personality and their Ukiyo-e skills. However, the higher the rank, the better chance that they would be chosen. There were gifts such as crests from the shogunate in the house using this family crest. Utagawa Kazumon did not only pay attention to the aesthetic of the picture, but also tried to maintain a close relationship with the masses, calling himself “painter”.[4]

Shita-e

[edit]Shita-e drawings are still used in the present time, with rough sketches and more refined brush paintings, on different kinds of paper with and without corrections, depending on the artist. Moreover, since the final drawing will be carved away, the drawings that would remain would be either sketches or copies of the final shita-e. It is still uncertain who produced the final shita-e, however the clues that remain are the series of sketches and corrections in red ink. More research remains to be done in this area, yet one reason for the vast success of the Utagawa School and its ability to support so many artists was the studio setup of printmaking in the nineteenth century. Paradoxically, the focus on a limited number of great printmakers of the day actually increased their standing and sales, and so supported the pupils beneath them.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Biography of Utagawa Hiroshige in: Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2014). 100 Famous Views of Edo. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00HR3RHUY

- ^ a b Johnson, Ken, "Fleeting Pleasures of Life In Vibrant Woodcut Prints", art review in The New York Times, March 22, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008

- ^ "Lines of Descent: Masters and Students of the Utagawa School". asianartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- ^ a b Amatori, Franco; Jones, Geoffrey, eds. (2003), "Business History around the World", Cambridge University Press, pp. xvii–xviii, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511512100.001, ISBN 9780511512100

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

[edit]- Kuniyoshi Project

- Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, has a collection of more than 4,000 Japanese prints in its E. B. Van Vleck Collection