William Lobb

William Lobb | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1809 Bodmin, United Kingdom |

| Died | 3 May 1864 (aged 54–55) San Francisco, United States |

| Occupation | Plant collector |

| Known for | Introduction of North and South American trees such as the monkey-puzzle tree to the United Kingdom |

William Lobb (1809 – 3 May 1864) was a British plant collector, employed by Veitch Nurseries of Exeter, who was responsible for introducing to commercial growers Britain Araucaria araucana (the monkey-puzzle tree) from Chile and the massive Sequoiadendron giganteum (Wellingtonia) from North America.

He and his brother, Thomas Lobb, were the first collectors to be sent out by the Veitch nursery business, with the primary commercial aim of obtaining new species and large quantities of seed.[2] His introductions of the monkey-puzzle tree, Wellingtonia and many other conifers to Europe earned him the sobriquet "messenger of the big tree".[3] In addition to his arboreal introductions, he also introduced many garden shrubs and greenhouse plants to Victorian Europe, including Desfontainia spinosa and Berberis darwinii, which are still grown today.

Early life

[edit]Lobb was born in 1809 at Lane End, Washaway near Bodmin Cornwall[4] and spent his early life at Egloshayle, near Wadebridge.[5] He had four brothers and two sisters. Two of the brothers, Henry and James, became managers of gunpowder plants in south-west England. His father, John Lobb, was the estate carpenter at nearby Pencarrow[6] where a notable garden had been developed by Sir William Molesworth. John developed a love of gardening and, after losing his place at Pencarrow, he took up employment at Carclew House, near Falmouth, the home of Sir Charles Lemon.[6] Sir Charles would later be amongst the first people in England to receive and grow rhododendron seed from Sir Joseph Hooker, who had sent seed directly to Sir Charles from his Himalayan expedition of 1848–1850.[6]

William, along with his younger brother Thomas, worked in the stove-houses at Carclew where Sir Charles encouraged the Lobb boys in their study of horticulture and botany.[6] In 1837, William was engaged by Mr Stephen Davey of Redruth, where he helped establish a "thoroughly efficient" horticultural establishment.[7] From there, he moved on to become gardener to the Williams family at Scorrier House, near Falmouth.[8] He gained a reputation as a keen amateur botanist and assembled a fine collection of dried specimens of British plants, particularly Cornish ferns, but had an increasing desire to travel abroad and to discover unknown "vegetation".[8]

By the late 1830s, James Veitch had established his plant nursery at Mount Radford, Exeter and was looking for ways to extend the range of plants on offer, thus improving the profitability of the business.[9] After correspondence with the eminent botanist Sir William Hooker about the most suitable destination, Veitch decided to employ his own plant hunter to gather exotic plants from South America exclusively for his nursery.[8] William's brother Thomas had been employed by Veitch since 1830 and recommended William to Veitch. Veitch was impressed by William's keen manner and horticultural knowledge;[8] according to the account in Hortus Veitchii, William:

was quick of observation, ready in resources, and practical in their application; he had devoted much of his leisure to the study of botany, in which considerable proficiency had been acquired.[7]

Veitch decided that William, despite not being a trained botanist, would prove a steady, industrious and dependable collector.[8] He therefore booked him a passage on HM Packet Seagull, which was to set sail from Falmouth on 7 November 1840,[8] bound for Rio de Janeiro and Lobb thus became the first of a long line of plant collectors to be sent out by the Veitch family to all corners of the world. James Veitch was anxious to ensure that Lobb should not be "cramped for funds"[9] and arranged for an annual allowance of £400 to be made available to draw on in the large cities along his planned itinerary.[10]

Before his departure, Lobb visited Kew Gardens where he was taught how to make herbarium specimens by placing plant material between special papers.[10]

South America (1840–1844)

[edit]Brazil and Argentina

[edit]Lobb took with him seeds of the early Rhododendron hybrid "Cornish Early Red" (R. arboreum x R. ponticum) as a gift from Veitch to the new emperor of Brazil, Pedro II. The seeds were planted in the gardens of the Imperial Palace at Petrópolis where they are still growing today.[11]

Following his arrival at Rio de Janeiro, Lobb spent 1841 exploring the Serra dos Órgãos (Organ Mountains)[7] to the north-east of the port where he discovered several orchids including the swan orchid, Cycnoches pentadactylon, as well as Begonia coccinea and Passiflora actinia.[9] His first shipment of discoveries, which arrived at Topsham dock in March 1841,[12] also included a new species of Alstroemeria, an Oncidium, O. curtum (with yellow flowers and cinnamon-brown markings), and a new red Salvia. There were also several species of the beautiful pink-flowered climber Mandevilla, including M. splendens, which would become highly sought after for cultivation in England, and the small shrub Hindsia violacea, with its clusters of ultramarine flowers, which quickly became popular in Victorian greenhouses.[12] The next shipment arrived at Topsham in May but had been delayed at Rio de Janeiro and, as a result, many of the plants failed to survive the journey, arriving dead or "vegetated".[12]

Later in 1841, Lobb travelled by boat to Argentina, where he spent the winter exploring the area around Buenos Aires. In January 1842, he sent back five cases of plants, seeds and dried specimens, but unfortunately the ship was unable to dock at Exeter as expected and continued on to Leith in Scotland, from where the packages eventually reached Exeter.[13]

Lobb then travelled overland to Chile via Mendoza and the Uspallata Pass over the Andes, thus avoiding the perilous sea voyage around Cape Horn.[9] Lobb found the journey through the mountains gruelling, having to travel through snow that he described as "five feet deep, frozen so hard that the mules made no impression and the cold was intense",[13] causing him to collapse ill with fever on several occasions.

Chile

[edit]

James Veitch's instructions to Lobb included a request to locate and bring back seeds of the Chile pine (more popularly known as the monkey-puzzle tree) (Araucaria araucana) which had originally been introduced to Britain by Archibald Menzies in 1795.[10] Veitch had seen a young specimen at Kew Gardens grown from seed brought back by the Horticultural Society's collector James McRae in 1826, and was convinced that this tree would be hugely popular as an ornamental plant.[10]

Once Lobb had recovered from the ordeal of his Andean crossing he left Valparaíso and travelled south by steamship to Concepción from where he set off to the forests of the Araucanía Region.[13] At 5,250 feet, he reached his destination where the sought-after Araucaria araucana was growing on the exposed ridges below the snow-capped volcanic peaks of the southern Andes.[14] Lobb collected over 3,000 seeds[2] by shooting cones from the trees while his porters gathered fallen nuts from the ground.[13][14] Lobb then returned to Valparaíso with the sacks containing the seeds and personally saw them onto a ship bound for England.[13] The shipment arrived safely at Exeter and by 1843 Veitch was offering seedlings for sale at £10 per 100.[13][14]

Unknown to his employers, Lobb also sent seeds back to his former employers, Sir Charles Lemon at Carclew and John Williams of Scorrier House,[15] where a plantation of monkey-puzzle trees was grown.[16]

During 1842, Lobb collected from the Valparaíso area and sent back seeds of a purple nasturtium climber, Tropaeolum azureum, which he located at "Cuesta Dormeda, about sixteen leagues (50 miles) from Valparaíso".[13] He also sent the pale-blue mallow, Abutilon vitifolium, and the white, rosemary–scented Calceolaria alba, which was the forerunner of many Calceolarias which were to become popular as summer bedding plants.[13]

Lobb then travelled by steamship to Talcahuano and then to Los Ángeles, from where he went inland towards the mountains following the Laja River upstream to the Antuco volcano. He then followed the Andes to Santa Bárbara regularly making excursions up to the snow line.[17] Lobb found this expedition exhausting and the eventual shipment back to England was disappointing with only one significant new discovery, a magenta flowering perennial Calandrinia umbellata.[17]

Lobb's travels then continued through northern Chile, where he discovered Desfontainia spinosa,[18] before moving on through Peru to Ecuador.

Peru, Ecuador and Panama

[edit]En route, he collected the passion flower, Passiflora mollissima (now P. tripartita var. mollissima), which became popular in greenhouses,[19] and the delicate Calceolaria amplexicaulis.[18]

In the spring of 1843, he took four cases of plants, which he had collected on the slopes of the Peruvian Andes, by sea to the Ecuadorian port of Guayaquil. While he was there, an epidemic of yellow fever broke out and, along with other European residents, he was forced to move to Puná Island until the epidemic was over, leaving his cases with a shipping agent to send to England.[20] On leaving Puná, Lobb hired mules and a guide and travelled inland to Quito and on into southwestern Colombia.[20]

He eventually reached the port of Tumaco, with a further collection of plants, from where he sailed for Panama intending to travel on with his latest finds back to England. On arriving at Panama City however, he received news from James Veitch that the cases of plants left in Guayaquil had never arrived. Lobb therefore despatched his latest collection from Panama (which arrived safely at Exeter) and awaited instructions from Veitch.[20]

Amongst the shipments from Panama were several orchids including Oncidium ampliatum collected near Panama City, described by Veitch in a letter to Hooker as arriving "quite fresh but others are rotten",[20] a blue-azure Clitoria and a Lobelia, Centropogon coccineus, which he found growing "in shady places on the banks of the Chagres River"[20] as well as seeds of several Fuchsias and Tropaeolum.

While waiting in Panama, Lobb continued to seek out new plants despite suffering from an attack of dysentery. Once he had recovered, he returned to Guayaquil where he discovered all his cases rotting in a corner of a warehouse, with much of the contents destroyed by ants. The agent explained that the cases had "quite escaped his notice".[20] Lobb was able to rescue some of the seeds, bulbs and dried specimens which he sent to Exeter. Veitch replied by sending back a supply of glass to make new shipping cases and insisting that Lobb endeavour to replace everything that was lost.[20]

Despite being exhausted from his travels and repeated attacks of ill health, Lobb returned to the interior of Peru for a further four months, finally arriving back in England in May 1844.[20] On Lobb's return to Exeter, Veitch wrote to Hooker:

I was disappointed at hearing William Lobb had left Peru, but pleased to hear of his safe arrival in England with many plants and seeds in good order. He reached Exeter with his plants on Saturday and is now gone to his friends.[20]

Amongst the dried samples sent back to England was one of Solanum lobbianum which was sent to Kew Gardens where it was labelled as "Lobb Columbia". It was named after its discoverer by Georg Bitter (1873–1927), the German expert on Solanum, based on the single specimen at Kew. For a long time there was some doubt about the actual location of the plant's discovery until it was re-discovered in Ecuador by an American expedition in the 1990s.[4]

It has been suggested that it was William Lobb who in 1844 brought the knowledge that gunpowder could be made with sodium nitrate from Peru to Cornwall, in England.[22] Until then, gunpowder in Britain and the rest of Europe had been made only with potassium nitrate.

On his travels Lobb would undoubtedly have met and talked to his fellow Cornishmen living in Peru/Chile and employed by the mines. There were significant numbers there.[23] Lobb was familiar with the use and manufacture of gunpowder for mining, having grown up near the two gunpowder plants at Ponsanooth, Cornwall.[24] Also, as a professional gardener, he would have known about sodium nitrate, which was widely used as a fertilizer in Britain at that time.

The 1841 census shows that while William was in South America, his brother, Henry Lobb, was living at Cosawes Woods (a local gunpowder plant) where he worked as a labourer.[25] Another brother, James Lobb, lived at nearby Perranwharf. He worked as a cooper.

Within two years of William's return, two additional plants had been built in Devon/Cornwall to make blasting powder. These were at Herodsfoot, Cornwall and at Powdermills on Dartmoor. Sodium nitrate was suitable for blasting powder, which was used in the mines and quarries of the region.[26] The sodium nitrate as received from Peru was of sufficient purity to be used without further treatment. This accounts for the absence at these two plants of the usual facilities for upgrading the potassium nitrate that came from India, which had a purity of only 65-70%. The manufacturing know-how probably came from the Perran Foundry. Barclay Fox, the owner of the Perran Foundry, certainly had some commercial interest in the second plant and a connection through the Quakers to the owners of the first.[27]

The 1851 census shows that fortune smiled on the Lobb family in the years after 1846.[28] Henry Lobb became the manager of the Herodsfoot plant and had a 1/6 share in the venture.[29] His brother-in-law and former neighbour, James Martin, became the manager of Dartmoor Powdermills; James Lobb was appointed its agent and, by 1861, its manager.

Was some sort of deal struck? Because of his background as a 'local', William Lobb would have had access to the right people at Perran Foundry, giving him the opportunity to pass on his valuable information about Peruvian gunpowder. The advancement of his brothers could have been William Lobb's reward.

South America (1845–1848)

[edit]

After a period of rest and recuperation, Lobb returned to work in the Exeter glasshouses planting out and nurturing his introductions.[30] By April 1845, his health had fully recovered and he was again despatched to South America with instructions to collect hardy and half-hardy trees and shrubs. After sending home from Rio Janeiro a consignment of plants collected in southern Brazil, he travelled by sea to Valparaíso in Chile from where he initially visited the montane forests of the Colombian Andes before visiting the extreme south of Chile from the shores of Tierra del Fuego to the southern coastal islands.[30]

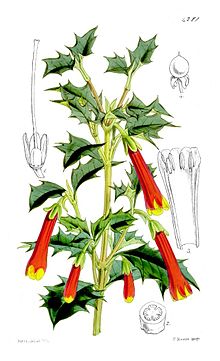

From the Valdivian temperate rain forests of Chile, Lobb brought back the Chilean firebush (Embothrium coccineum), the Chilean bellflower (Lapageria rosea) (the national flower of Chile), the flame nasturtium (Tropaeolum speciosum) and the Chilean lantern tree (Crinodendron hookerianum).[30] He also collected seeds of three species of myrtle tree, Luma apiculata, Ugni molinae and Luma chequen as well as "four most interesting Conifers for this country ... that South America produces"[31] – the Guaitecas cypress (Pilgerodendron uviferum), the Patagonian cypress (Fitzroya cupressoides), Prince Albert's yew (Saxegothaea conspicua) and Podocarpus nubigenus as well as seeds of the hardy Antarctic beech (Nothofagus antarctica) and several other shrubs including Escallonia macrantha.[30]

From a visit to Chiloé Island, Lobb introduced Berberis darwinii[18] which had been discovered in 1835 by Charles Darwin during the voyage of HMS Beagle. According to the Gardeners' Chronicle:

If Messrs. Veitch had done nothing else towards beautifying our gardens, the introduction of this single species would be enough to earn the gratitude of the whole gardening world.[30]

Lobb's finds were despatched to England where they were grown in Veitch's Exeter nursery before being sold to eager gardeners.[18] Many of his discoveries have endured and remain popular garden shrubs today.[32] One glasshouse at the Exeter nursery was reserved exclusively for William Lobb's discoveries, where James Veitch would tend the new plants and identify those that would become a commercial success and those that would be merely of botanical interest.[33] Amongst the plants sent back by Lobb were two species of Cantua which he found growing in Bolivia, Chile and the Peruvian Andes; C. buxifolia (the magic-flower) which was the first to flower in May 1848 and the bushy C. bicolor, with its large golden-red trumpet flowers.[33]

There were also other species of nasturtium, including Tropaeolum umbellatum from Ecuador, with its orange-tipped red flowers, and what was thought to be an unknown species which was named Tropaeolum lobbianum by Hooker after its discoverer, although this was later found to be a synonym for T. peltophorum previously discovered by Karl Theodor Hartweg.[33]

At the beginning of 1848, William Lobb arrived back in England and was re-united with his brother Thomas for the first time since setting off for Brazil in November 1840.[34] Thomas in the meantime had also been despatched by Veitch to collect plants in Malaysia and Indonesia and had returned a few months earlier.[35]

North America (1849–1853)

[edit]In 1849, Veitch decided to send William Lobb to collect in the cooler climate of North America in order to find conifers and hardy shrubs in Oregon, Nevada and California,[36] "with a view of obtaining seeds of all the most important kinds known, and, if possible, discover others."[31] Lobb reached San Francisco in the summer of 1849, at the height of the California Gold Rush; when he arrived the harbour was choked with hundreds of ships, abandoned by their crews who had joined the hopeful prospectors afflicted with "gold fever".[36] Lobb soon left the lawless port and set off in search of "horticultural gold" in Southern California.[37]

He spent the autumn of 1849 through to early 1851 in the Monterey area, including the Santa Lucia Mountains,[37] where he soon found the striking Santa Lucia fir (Abies bracteata),[38] later described by Hooker as "among the most remarkable of all true pines".[36] The cones sent back by Lobb were full of seed which were capable of being propagated by Veitch.[39] In 1849, he visited Cone Peak, in Los Padres National Forest[40] where he collected a new species of lupin, Lupinus cervinus (deer lupine) which he sold to the California Academy of Sciences. In 1862, Dr Albert Kellogg recognized this as a taxon hitherto unknown to science. Kellogg noted that this was "a very marked [distinct], fine [attractive], robust species, worthy of cultivation".[40]

In the Monterey area Lobb also found Rhododendron occidentale, one of only two deciduous Rhododendron species native to western North America which was to become the parent of many hybrid rhododendrons,[39] and a small horse chestnut, the California buckeye (Aesculus californica). He also sent back seeds of various other conifers, including the Monterey pine (Pinus radiata), the bishop pine (P. muricata), the gray pine (P. sabiniana), the Coulter pine (P. coulteri), and the knobcone pine (P. attenuata); and also of many shrubs and flowering plants, most quite new to British gardens.[39]

In the autumn of 1851, he moved north collecting large quantities of seed from the sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), and the western white pine (Pinus monticola); he also collected sackfuls of seed from the world's tallest tree, the California redwood (Sequoia sempervirens),[37] which had been first introduced by Patrick Matthew to Britain in 1853.

The following year, he moved further north into the regions explored by David Douglas in the 1820s, including the mountains of Oregon and the Columbia River.[41] On this expedition he collected seeds of the noble fir (Abies procera) and the Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) as well as three conifers that had been overlooked by Douglas, the Colorado white fir (Abies concolor), the red fir (Abies magnifica) and the western red cedar (Thuja plicata).[39] On his way back to San Francisco at the end of 1852, he collected seed from the grand fir (Abies grandis) and the ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and another new discovery, the California juniper (Juniperus californica).[39]

Lobb was the first collector to gather seed in bulk from trees that were still rare in England;[39] the amount of viable seed he sent to Exeter enabled Veitch & Sons to grow thousands of seedling trees.[41]

As well as the large number of conifers, Lobb discovered various shrubs including the red Delphinium cardinale, the yellow Fremontodendron californicum, a flowering currant Ribes lobbii (named after him) and a collection of Ceanothus including two natural hybrids, C. × lobbianus and C. × veitchianus which he found on the dry slopes and ridges of the high Californian chaparral.[39][41]

Wellingtonia

[edit]In 1853, Lobb was in San Francisco packing his collection of seeds to prepare them for shipment back to England when he received an invitation to a meeting of the newly formed California Academy of Science.[42] At the meeting, Dr Albert Kellogg (the academy's founder and a keen amateur botanist) introduced a hunter named Augustus T. Dowd who had brought to him a story of a "Big Tree".[41] Dowd told the audience that in the spring of 1852 he was employed as a hunter by the Union Water Company, of Murphy's Camp, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in Calaveras County, to supply the workmen, who were engaged in the construction of a canal, with fresh meat. He had been out chasing a large grizzly bear; the long, hard chase led Dowd into a strange part of the forested hills where he followed the bear into a grove of gigantic trees. Dowd soon lost interest in the chase and wandered around in amazement at the sheer size of the trees surrounding him. On returning to his camp, Dowd told his story to his companions, most of whom did not believe him and accused him of being drunk; a week later, however, he was able to persuade some of the less sceptical to be led to the grove, where they were equally astonished by the monstrous trees.[41][43]

Lobb immediately realised the impact such a tree would have on British gardens and the importance that his employers would attach to being the first nursery to offer it for sale.[41][42] After the meeting, he quickly headed to Calaveras Grove where he had the good luck to find a recently fallen tree, which he measured as "about 300 feet in length, 29 feet 2 inches, at 5 feet above the ground...".[43] In his notebooks, Lobb recorded: "From 80 to 90 trees exist all within circuit of a mile, from 250ft. to 320ft. in height, 10–12ft. in diameter."[44] He collected as many seeds, cones, vegetative shoots and seedlings as he could carry back to San Francisco, including two small living trees.[42] He then returned to England on the first available boat arriving back in Exeter on 15 December 1853,[45] a year earlier than expected. Lobb had taken a gamble cutting short his contract, knowing that, at the risk of angering his employer, he had to get the seeds to England before anyone else could get back first. The gamble paid off as Veitch was delighted, abandoning all other projects to concentrate on raising the seedlings in commercial quantities.[42] According to Hortus Veitchii, the two sapling trees "survived but three or four years, nor was there at any time much hope of their living."[38]

On Christmas Eve 1853, an editorial in The Gardeners' Chronicle announced that Veitch & Son "had received branches and cones of a remarkable tree from their collector in California, William Lobb" who had described it as "the monarch of the Californian forest".[42] James Veitch had immediately given specimens of the giant tree to John Lindley, professor of botany at the University of London and invited him to name the tree. In the Gardeners' Chronicle article, Lindley named the species Wellingtonia gigantea as a memorial to Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington who had died in September the previous year.[42] The "giant amongst trees" was considered an appropriate memorial for such an important British historical figure.[43]

Six months later, the Chronicle reported that Veitch was offering seedlings of the tree at 2 guineas each or 12 guineas a dozen.[44] Lobb could not claim to be first to introduce the tree to Britain, as a Scot, John Matthew,[46] had taken some seed to Scotland four months earlier although he only distributed the seed among a few friends.[42]

The Victorians fell in love with the tree in much the same way as they had with the monkey-puzzle tree a few years earlier,[2] using it as a specimen tree and often planting it to form avenues,[44] including James Bateman who planted an avenue at Biddulph Grange, alternating Wellingtonia with monkey-puzzle trees.[42] There is a good example of the tree in the garden of the manager's house at the gunpowder plant in Herodsfoot, Cornwall, where William's brother, Henry Lobb, lived for many years.

Unfortunately, the name Wellingtonia gigantea was invalid under the botanical code as the name Wellingtonia had already been used earlier for another unrelated plant (Wellingtonia arnottiana in the family Sabiaceae).[45] Eventually in 1939, after several attempts to find an acceptable name, the tree was given the name Sequoiadendron giganteum by John Buchholz.[45] In Britain, however, the tree remains known popularly as "Wellingtonia".[42]

Later career and death

[edit]By the middle of 1854, James Veitch and his son, James Veitch, Jr. (who had acquired premises in Kings Road, Chelsea, London in 1853), decided that it was time for William and his brother, Thomas, to be sent off again to collect fresh seed and search for yet more new plants.[47] Thomas was sent back to the far East, to Java and North Borneo in search of Nepenthes pitcher plants.

William had been suffering from persistent ill-health for some time – James Veitch remarked that there was "a sort of restlessness about him" – and was exhibiting the symptoms of syphilis, probably contracted in the ports of South America.[47] In a letter to Sir William Hooker, James Veitch noticed:

He seems taken with a sort of monomania, which it is difficult to describe and which he could not explain himself, a sort of excitability and want of confidence.[47]

Despite his concerns, in the autumn of 1854, Veitch sent Lobb back to California on another three–year contract. Lobb was unable to make any further new discoveries, but sent back consignments of plants and seeds from time to time until the end of 1856. In January 1857, Veitch wrote to Hooker: "We hear Lobb has been ill, his writing appears shaky and I am inclined to think it is probable he will soon return."[47]

In the event, Lobb did not return to England and after the expiry of his contract in 1858 he remained in California.[48] He sent back a small number of seeds to private collectors and to the Low nursery at Clapton, including a new variety of white fir (Abies concolor subsp. lowiana) (popularly known as "Low's white fir" after them) and the rare Torrey pine (Pinus torreyana).[48] James Veitch complained to Lobb that he still had obligations to fulfill but Lobb was undeterred and caused Veitch further embarrassment by sending herbarium specimens and live plants direct to Sir William Hooker at Kew Gardens.[48]

Communications from Lobb gradually ceased, to the alarm of both his family and Veitch, who wrote to Hooker: "We thought he had given up collecting plants, for Californian gold."[48] His last communication to his family was in 1860.[49]

On 3 May 1864, Lobb died forgotten and alone at St Mary's Hospital in San Francisco.[49][50] The cause of death was recorded as "paralysis",[51] but was probably as a result of syphilis.[52] He had no mourners at his burial (on 5 May)[49] in a public plot in Lone Mountain cemetery.[51] In 1927, his headstone was moved to South Ridge Lawn and in 1940 to a crypt at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park under the care of the California Academy of Sciences.[52]

A small memorial plaque can be found in Devoran church, Cornwall where his brother Thomas Lobb was buried in 1894.

Obituary

[edit]In Hortus Veitchii, the history of the Veitch family, Lobb's contribution to modern gardening is described thus:

The singular success which rewarded his researches is, perhaps, unparalleled in the history of botanical discovery; the labours of David Douglas not even forming an exception.[53]

In her history of the Veitch family, Seeds of Fortune – A Gardening Dynasty, Sue Shephard adds:

William was arguably one of the finest but least–known of collectors who gave gardeners some of the most remarkable trees and loveliest plants ever grown.[52]

Legacy

[edit]The old garden moss rose, 'William Lobb' was named after Lobb by its French breeder, Jean Laffay (1795–1878), in 1855.[54] It has deep purple flowers between three and four inches across with a strong scent.[55]

Amongst the many other plants named after William Lobb are:

- Eriogonum lobbii, a species of wild buckwheat known by the common name Lobb's buckwheat, native to the mountain ranges of northern California and their extensions into Oregon and Nevada.

- Eschscholzia lobbii, a species of Papaveraceae known by the common name frying pans, endemic to California, where it grows in the Central Valley and adjacent Sierra Nevada foothills.

- Palicourea lobbii, a species in the family Rubiaceae, endemic to Ecuador.

- Ribes lobbii, the gummy gooseberry found in Northern California.[56]

- Salvia lobbii, a species of flowering plant in the family Lamiaceae, endemic to Ecuador.

William Lobb is a character in Tracy Chevalier's novel At the Edge of the Orchard (Penguin Books, 2016).

References

[edit]- ^ Redwood World - Redwoods in the British Isles

- ^ a b c Julia Brittain (2006). The Plant Lover's Companion: Plants, People & Places. David & Charles. p. 119. ISBN 1-55870-791-3.

- ^ Joseph Andorfer Ewan (1973). "William Lobb, plant hunter for Veitch and messenger of the big tree". University of California Press. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ a b John G. Hawkes (1992). "William Lobb in Ecuador and the Enigma of Solanum lobbianum". Taxon. 41 (3): 471–475. doi:10.2307/1222817. JSTOR 1222817. and offline Taxon, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Aug., 1992), pp. 471-475.

- ^ "CORNWALL GARDENS TRUST » Journal » Lobb's Cottage". www.cornwallgardenstrust.org.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Toby Musgrave, Chris Gardner & Will Musgrave (1999). The Plant Hunters. Seven Dials. p. 134. ISBN 1-84188-001-9.

- ^ a b c James Herbert Veitch (2006). Hortus Veitchii (reprint ed.). Caradoc Doy. p. 37. ISBN 0-9553515-0-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Sue Shephard (2003). Seeds of Fortune - A Gardening Dynasty. Bloomsbury. p. 78. ISBN 0-7475-6066-8.

- ^ a b c d Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 79.

- ^ "A History of Rhododendrons". Vancouver Rhododendron Society. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ a b c Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 83.

- ^ a b c Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 138.

- ^ Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 94.

- ^ Christian Lamb (2004). From the Ends of the Earth: Passionate Plant Collectors Remembered in a Cornish Garden. Christian Lamb. p. 147. ISBN 1-903071-08-9.

- ^ a b Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 140.

- ^ Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. pp. 96–97.

- ^ Ashford, Bob (2016). "A New Interpretation of the Historical Data on the Gunpowder Industry in Devon and Cornwall". J. Trevithick Soc. 43. Camborne, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society: 70.

- ^ Ashford, Bob (2014). "Some Thoughts on Dartmoor Powdermills". Rep. Trans. Devon. Ass. Advmt Sci. 146. Exeter: The Devonshire Association: 66.

- ^ "Cornish Mining in South America". Cornish Mining World Heritage Site. 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Earl, Bryan (2006). Cornish Explosives (Second ed.). Redruth: The Trevithick Society. ISBN 9780904040685.

- ^ "1841 Census by Hundreds". Cornwall Online Census Project. Ancestry.com. 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "1857 Lammot du Pont". Innovation Starts Here. E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Ashford, Bob (2014). "Some Thoughts on Dartmoor Powdermills". Rep. Trans. Devon. Ass. Advmt Sci. 146. Exeter: The Devonshire Association: 62–63.

- ^ "1851 Census by Hundreds". Cornwall Online Census Project. Ancestry.com. 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Day, Paul (2011). "Herodsfoot and Trago Mills Gunpowder and Explosives Works, Liskeard, 1845-1965". Journal of the Travithick Society. 38. Redruth: The Trevithick Society: 85.

- ^ a b c d e Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. pp. 99–100.

- ^ a b Hortus Veitchii. p. 38.

- ^ Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 89.

- ^ a b c Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 86.

- ^ Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 143.

- ^ Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 101.

- ^ a b c Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 107.

- ^ a b c Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 146.

- ^ a b Hortus Veitchii. p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 108.

- ^ a b David Rogers. "Unique and Noteworthy Plants of the Santa Lucia Mountains – Lupinus cervinus". ventanawild.org. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 147.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b c "The "discovery" and naming of Sequoiadendron giganteum". oregonstate.edu. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ a b c Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 148.

- ^ a b c Christopher J. Earle. "Sequoiadendron giganteum (Lindley) Buchholz 1939". University of Hamburg. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ "The History of Cluny – The Plant Collectors". clunyhousegardens.com. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ a b c d Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b c d Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 126.

- ^ a b c Musgrave. The Plant Hunters. p. 149.

- ^ Shirley Heriz-smith (2007). Roger Trenoweth (ed.). The Cornish Garden. The Cornwall Garden Society. pp. 80–9.

- ^ a b Hortus Veitchii. p. 40.

- ^ a b c Shephard. Seeds of Fortune. p. 151.

- ^ Hortus Veitchii. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Paul Barden. "Old Garden Roses – William Lobb". rdrop.com. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ "Garden plants and their hunters – William Lobb". blueworldgardener.co.uk. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ "Ribes lobbii". calflora.org. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

External links

[edit]- International Plant Names Index entry

- Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California (1862) – The Mammoth Trees Of Calaveras

- A History of British Gardening (BBC) – William and Thomas Lobb

- A History of British Gardening (BBC) – The Monkey Puzzle tree and Wellingtonia

- The Lobb Brothers and their Famous Plants (Caradoc Doy)

- "The Plant Collectors" (PDF). (111.76 KiB)