Lubusz Land

Lubusz Land Ziemia lubuska, Land Lebus | |

|---|---|

| |

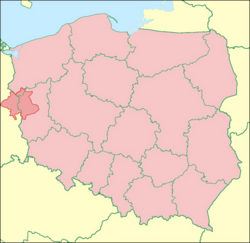

Lubusz Land on the map of Poland | |

| Country | |

| Historical capital | Lebus |

| Largest city | Frankfurt (Oder) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Highways | |

Lubusz Land (Polish: Ziemia lubuska; German: Land Lebus) is a historical region and cultural landscape in Poland and Germany on both sides of the Oder river.

Originally the settlement area of the Lechites, the swampy area was located east of Brandenburg and west of Greater Poland, south of Pomerania and north of Silesia and Lower Lusatia. Presently its eastern part lies within the Polish Lubusz Voivodeship, the western part with its historical capital Lebus (Lubusz) in the German state of Brandenburg.

History

[edit]Kingdom of Poland

[edit]

When in 928 King Henry I of Germany crossed the Elbe river to conquer the lands of the Veleti, he did not subdue the Leubuzzi people settling beyond the Spree. Their territory was either already inherited by the first Polish ruler Mieszko I (~960-992) or conquered by him in the early period of his rule. After Mieszkos' death the whole country was inherited by his son Duke, and later King, Bolesław I the Brave. After the German Northern March got lost in a 983 Slavic rebellion, Duke Bolesław and King Otto III of Germany in 991 agreed at Quedlinburg to jointly conquer the remaining Lutician territory, Otto coming from the west and Bolesław starting from Lubusz in the east. However, they did not succeed. Instead Otto's successor King Henry II of Germany in the rising conflict over the adjacent Lusatian march concluded an alliance with the Lutici and repeatedly attacked Bolesław.

Lubusz Land remained under Polish control even after King Mieszko II Lambert in 1031 finally had to withdraw from the adjacent, just conquered March of Lusatia and accept the overlordship of Emperor Conrad II. In 1125 Duke Bolesław III Wrymouth of Poland established the Bishopric of Lubusz to secure Lubusz Land. 1124-1125 records note that the new Bishop of Lubusz was nominated by Duke Bolesław under the Archbishopric of Gniezno. However, from the beginning Gniezno's role as metropolia of the Lubusz diocese was challenged by the claims of the mighty Archbishops of Magdeburg, who also tried to make Lebus their suffragan. The Polish position was decisively enfeebled by the process of fragmentation after the death of Duke Bolesław III in 1138, when Lubusz Land became part of the Duchy of Silesia.[1] The Duchy of Silesia was restored to the descendants of Władysław II the Exile in 1163, and Lubusz Land together with Lower Silesia was given to his eldest son Bolesław I the Tall.

In the 13th century Polish dukes in order to help develop Lubusz Land, granted some areas to different Catholic religious orders, such as the Cistercians, Canons Regular and Knights Templar. Among those orders possessions were Łagów, Chwarszczany, Lubiąż (today's Müncheberg) and Dębno.[2]

Lubusz remained under the rule of the Silesian Piasts, though Bolesław's son Duke Henry I the Bearded in 1206 signed an agreement with Duke Władysław III Spindleshanks of Greater Poland to swap it for the Kalisz Region. This agreement however did not last as it provoked the revolt of Władysław's nephew Władysław Odonic, while in addition the Lusatian margrave Conrad II of Landsberg took this occasion to invade Lubusz. Duke Henry I appealed to Emperor Otto IV and already started an armed expedition, until he was once again able to secure his possession of the region after Margrave Conrad had died in 1210. Nevertheless, the resistance against the Imperial expansion waned as the Silesian territories were again fragmented after the death of Duke Henry II the Pious at the Battle of Legnica in 1241. His younger son Mieszko then held the title of a "Duke of Lubusz", but died only one year later, after which his territory fell to his elder brother Bolesław II the Bald. In 1248 Bolesław II, then Duke of Legnica, finally sold Lubusz to Magdeburg's Archbishop Wilbrand von Käfernburg and the Ascanian margraves of Brandenburg in 1249, wielding the secular reign.

March of Brandenburg and Kingdom of Bohemia

[edit]As to secular rule Lubusz Land was finally separated from Silesia, according to canon law however, the Lubusz diocese, comprising most of Lubusz Land, remained subordinate to the Gniezno metropolis. Meanwhile, the Brandenburg margraves forwarded the incorporation of Lubusz Land into their New March, created and expanded further to the northeast after the acquisition of the Santok castellany in 1296 on the forest areas between the Duchy of Pomerania and Greater Poland.

The Lebus bishops tried to maintain their affiliation with Poland and in 1276 therefore moved their residence east of the Oder river to Górzyca (Göritz upon Oder), an episcopal fief. When in 1319 the Brandenburg House of Ascania became extinct, the Lubusz Land became the subject of rivalry between the Piasts (duchies of Jawor and Żagań), Griffins (Duchy of Pomerania) and the Ascanians (Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg).[3] In 1319, the region was captured by Wartislaw IV, Duke of Pomerania, in 1320 a large portion passed to Duke Henry I of Jawor, who tried to reclaim the Lubusz Land as region lost by his grandfather Bolesław II the Horned, later that year the western part was conquered by Rudolf I, Duke of Saxe-Wittenberg, and the eastern outskirts with Torzym were controlled by Duke Henry IV the Faithful of Żagań by 1322.[4] In 1322–1323, there were heavy fights between Pomerania and Saxe-Wittenberg in the northern part of the region, around Kostrzyn nad Odrą.[5]

After the Battle of Mühldorf, the House of Wittelsbach took an interest in the region in 1323, and King Louis IV the Bavarian decided to grant the Margraviate of Brandenburg with the Lubusz Land to his son Louis V.[6] The emergence of a new powerful rival prompted the previously warring parties to make peace with each other and cooperate.[6] Bavarian forces soon entered the region, but in October 1323 Pope John XXII called Louis IV to annul the grant of Brandenburg to Louis V, declaring it unlawful.[7] The Pope supported the dukes of Pomerania and Głogów and local bishop Stephen II, and urged the region's inhabitants to resist the Wittelsbachs.[8] King Władysław I the Elbow-high of Poland also took the chance, allied with Bishop Stephen II and campaigned the Lubusz Land. In return the head of secular government in Lubusz, governor Erich of Wulkow, loyal to the new Brandenburg margrave Louis V, raided and captured the episcopal possessions in 1325, burning down the Górzyca cathedral. Bishop Stephen fled to Poland.

In 1354 Bishop Henry Bentsch reconciled with Margrave Louis II and the episcopal possessions were returned. The see of the bishopric returned to Lebus, where a new cathedral was built. In 1373 the diocese was again devastated by a Bohemian army, when Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg took the Brandenburg margraviate from the House of Wittelsbach. It became part of the Lands of the Bohemian (Czech) Crown. The see of the bishopric now moved to Fürstenwalde (Przybór) (St Mary's Cathedral, Fürstenwalde). Polish monarchs still made peaceful attempts to regain the region. The northern part of the diocese of Lubusz, the Kostrzyn land, administratively became part of the New March, a peripheral region for Czech rulers who were willing to sell it. In 1402, an agreement was reached in Kraków between them and the Poles, under which Poland was purchase and reincorporate this region,[9] however in the same year the Luxembourgs sold the region to the Teutonic Knights, Poland's arch-enemy. In 1454, after the Thirteen Years’ War broke out, the Teutonic Knights sold the region to Brandenburg in order to raise funds for war against Poland. The bulk of the Lubusz Land remained part of the Bohemian (Czech) lands until 1415.

In 1424 the Lebus bishopric became a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Magdeburg, finally leaving the Gniezno ecclesiastical province. In 1432, the Czech Hussites captured the city of Frankfurt (Oder).[10] In 1518 Bishop Dietrich von Bülow bought the secular lordship of Beeskow-Storkow, in secular respect a Bohemian fief, in religious respect mostly no part of his diocese but of the Diocese of Meissen.[11] The castle in Beeskow became the episcopal residence. The last Catholic bishop was Georg von Blumenthal, who died in 1550 after a heroic non-military counter-reformatory campaign. However, when in 1547 Bishop Georg tried to recruit and arm troops in order to join the Catholic Imperial forces in the Smalkaldic War, his vassal city of Beeskow refused to obey.

From 1555 the bishopric was secularised and became a Lutheran diocese and the area east of the Oder was later called Eastern Brandenburg. In 1575 King Maximilian II of Bohemia granted the Beeskow lordship of the Lebus diocese to Brandenburg as a Bohemian fief, which it remained until the First Silesian War in 1742.[12] When in 1598 the Magdeburg administrator Joachim Frederick of Hohenzollern became Elector of Brandenburg, all official links with Poland had long been cut.

In the 16th century, many Polish exports, including grain, wood, ash, tar and hemp, were floated from western Poland via Frankfurt (Oder) in Lubusz Land to the port of Szczecin, with the high Brandenburgian customs duties on Polish goods lowered in the early 17th century.[13]

Prussia and Germany

[edit]

But new links to Poland developed, because since 1618 the prince-electors of Brandenburg ruled the Duchy of Prussia, then a Polish vassal state, in personal union. In 1657 Prussia gained sovereignty, so in 1701 the electors could upgrade their simultaneously held Prussian dukedom to the Kingdom of Prussia, dropping the title of elector of the Holy Roman Empire at its dissolution in 1806. In 1815 the kingdom joined the German Confederation, in 1866 the North German Confederation, which enlarged in 1871 to united Germany.

By the 17th century most of the population, consisting of autochthon Poles and German settlers, had mingled and assimilated to German language.

One of the main escape routes for insurgents of the unsuccessful Polish November Uprising from partitioned Poland to the Great Emigration led through the region.[14]

During World War I, a German strict regime prisoner-of-war camp for French, Russian, Belgian, British and Canadian officers was operated in Kostrzyn.[15] Notable inmates included Leefe Robinson, Jocelyn Lee Hardy, Roland Garros and Jules Bastin, who all made unsuccessful escape attempts.[16] It is considered the only German POW camp of World War I from which no one managed to escape.[17]

World War II

[edit]

The Einsatzgruppe VI was formed in Frankfurt (Oder) before it entered several Polish cities, including Poznań, Kalisz and Leszno, to commit various crimes against Poles during the German invasion of Poland, which started World War II.[18] During the war, the Germans operated the Stalag III-C prisoner-of-war camp for Polish, French, Serbian, Soviet, Italian, British, American and Belgian POWs in the region,[19] and numerous forced labour camps, including several subcamps of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, whose prisoners were Poles, Ukrainians, Russians, Norwegians, French, Belgians, Germans, Jews and Dutch.[20][21] Particularly infamous camps were the Oderblick labor education camp in Świecko and the Sonnenburg concentration camp in Słońsk, in which Polish, Belgian, French, Bulgarian, Dutch, Yugoslav, Russian, Italian, Ukrainian, Luxembourgish, Danish, Norwegian, Czech, Slovak and other prisoners were held, and many died.[22][23]

In early 1945, the death marches of prisoners of various nationalities from the dissolved camps in Świecko and Żabikowo to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp passed through the region.[22][24] On 30–31 January, the SS and Gestapo perpetrated a massacre of over 800 prisoners of the Sonnenburg concentration camp.[23]

Lubusz Land was the site of fierce fighting on the Eastern Front of World War II in 1945. In February and March the battle for Kostrzyn nad Odrą (then Küstrin) was fought, which resulted in 95% of the town being destroyed,[25] making it the most destructed town of post-war Poland. Shortly after the liberation of the Stalag III-C POW camp in Kostrzyn, Soviet troops killed some American POWs mistaking them for German troops.[19] In April the Battle of the Seelow Heights took place, ending in a Soviet-Polish victory. It was one of the last battles before the capitulation of Nazi Germany and the end of World War II in Europe.

In Poland and Germany

[edit]

The portion of Lubusz Land east of the Oder River became again part of Poland by the 1945 Potsdam Conference, although with a Soviet-installed communist regime, which stayed in power until the 1980s, whereas the western portion with the historical capital Lebus remained under Soviet occupation and became a part of communist East Germany in 1949.

Polish and Soviet authorities expelled most of the German population from the Polish annexed part of Lubusz Land in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement. Refugees who had fled before the Soviet forces were prevented from returning to their homes. The area was then resettled with Poles expelled from Soviet-annexed eastern Poland and migrants from central Poland. The largest cities and capitals of the Polish Lubusz Voivodeship today are Zielona Góra and Gorzów Wielkopolski, which however were not part of the historical Lubusz Land (cf. map above), but were parts of Lower Silesia and Greater Poland (the Santok castellany) respectively. Today, the largest town of Lubusz Land is Frankfurt (Oder), located in the German part of the region. On the Polish side the largest town is Kostrzyn nad Odrą. The region's historic capital, Lebus, is one of the smallest towns.

In the Polish part of the Lubusz Land, in Słubice, the Wikipedia Monument, world's first monument dedicated to the Wikipedia community, was unveiled in 2014.[26]

Towns

[edit]See also

[edit]External links

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Zientara, Benedykt (2006). Henryk Brodaty i jego czasy (in Polish). Trio. pp. 193–96. ISBN 83-7436-056-9.

- ^ Codex diplomaticus Majoris Polonia, tom XI

- ^ Rymar, Edward (1979). "Rywalizacja o ziemię lubuską i kasztelanię międzyrzecką w latach 1319–1326, ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem stosunków pomorsko-śląskch". Śląski Kwartalnik Historyczny Sobótka (in Polish). XXXIV (4). Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk: 481.

- ^ Rymar, pp. 481, 485–486, 489

- ^ Rymar, p. 489

- ^ a b Rymar, p. 492

- ^ Rymar, p. 493

- ^ Rymar, pp. 493–494

- ^ Rogalski, Leon (1846). Dzieje Krzyżaków oraz ich stosunki z Polską, Litwą i Prussami, poprzedzone rysem dziejów wojen krzyżowych. Tom II (in Polish). Warszawa. pp. 59–60.

- ^ Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, Tom II (in Polish). Warszawa. 1881. p. 402.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dirk Schumann, Beeskow (12001), Sibylle Badstübner-Gröger and Christine Herzog (collab.) for the Freundeskreis Schlösser und Gärten der Mark (ed.), slightly altered ed., Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft, 22006, (Schlösser und Gärten der Mark; part: Beeskow), p. 4. No ISBN

- ^ Dirk Schumann, Beeskow (12001), Sibylle Badstübner-Gröger and Christine Herzog (collab.) for the Freundeskreis Schlösser und Gärten der Mark (ed.), slightly altered ed., Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft, 22006, (Schlösser und Gärten der Mark; part: Beeskow), p. 7. No ISBN

- ^ Rutkowski, Jan (1923). Zarys gospodarczych dziejów Polski w czasach przedrozbiorowych (in Polish). Poznań. pp. 200–201.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Umiński, Janusz (1998). "Losy internowanych na Pomorzu żołnierzy powstania listopadowego". Jantarowe Szlaki (in Polish). No. 4 (250). p. 16.

- ^ Orłow, Aleksander (2011). "Oficerski obóz jeniecki twierdzy Kostrzyn nad Odrą 1914−1918". In Mykietów, Bogusław; Bryll, Wolfgang Damian; Tureczek, Marceli (eds.). Forty. Jeńcy. Monety. Pasjonaci o Twierdzy Kostrzyn (in Polish). Zielona Góra: Księgarnia Akademicka. pp. 18, 21.

- ^ Orłow, pp. 22−24

- ^ Orłow, p. 27

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 60.

- ^ a b Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 408–409. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ "Anlage zu § 1. Verzeichnis der Konzentrationslager und ihrer Außenkommandos gemäß § 42 Abs. 2 BEG" (in German). Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2009). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume I. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 1303–1305, 1321–1322, 1345. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- ^ a b "Świecko (Lager Schwetig): Odnaleziono szczątki 21 osób". Instytut Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Słońsk: 73. rocznica zagłady więźniów niemieckiego obozu Sonnenburg". dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Ewakuacja piesza". Muzeum Martyrologiczne w Żabikowie (in Polish). Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Andrzej Toczewski. "Bitwa o Festung Küstrin w 1945 roku". Konflikty.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ "World's first Wikipedia monument unveiled in Poland". TheNews.pl. Retrieved 18 October 2019.