Zorawar Singh (Sikhism)

Sahibzada Baba Zorawar Singh Ji | |

|---|---|

ਜ਼ੋਰਾਵਰ ਸਿੰਘ, ਸਾਹਿਬਜ਼ਾਦਾ | |

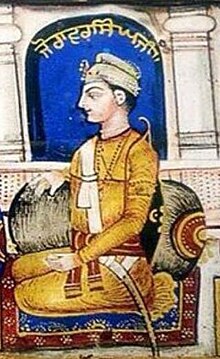

Detail of Sahibzada Zorawar Singh from a mural depicting Guru Gobind Singh and his four sons (the Sahibzadas) located within Takht Hazur Sahib | |

| Title | Sahibzada |

| Personal | |

| Born | 17 November 1696 Anandpur, India |

| Died | 5 or 6 December 1705 Fatehgarh Sahib, India |

| Cause of death | Extrajudicial execution by Immurement |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Parent(s) | Guru Gobind Singh, Mata Jito |

| Relatives | Sahibzada Ajit Singh (half-brother) Sahibzada Jujhar Singh (brother) Sahibzada Fateh Singh (brother) |

Zorawar Singh (Punjabi: ਸਾਹਿਬਜ਼ਾਦਾ ਜ਼ੋਰਾਵਰ ਸਿੰਘ, pronunciation: [säːɦɪbd͡ʒäːd̪ɛ d͡ʒoɾäːʋaɾ sɪ́ŋgᵊ]; 17 November 1696 – 5 or 6 December 1705[1]), alternatively spelt as Jorawar Singh,[2] was a son of Guru Gobind Singh who was executed in the court of Wazir Khan, the Mughal Governor of Sirhind.

Background

[edit]In 1699, the Hindu Rajahs of the Shiwalik Hills, frustrated with increasing Sikh ascendancy in the region, requested aid from Aurangzeb; their combined forces took on the Khalsa, led by Guru Gobind Singh, at Anandapur but were defeated.[3] Another faceoff followed in the neighboring Nirmoh but ended in Sikh victory; there was probably another conflict in Anandapur (c. 1702) to the same outcome.[3] In 1704, the Rajahs mounted a renewed offensive against Guru Gobind Singh in Anandapur, but facing imminent defeat, requested aid from Aurangzeb.[3] While the Mughal subahdars came to aid, they failed to change the course of the battle.[3] Accordingly, the Rajahs decided to lay siege to the town rather than engage in open warfare.[3]

With the passage of a few uneventful months, as scarcity of food set in, Guru Gobind Singh's men compelled him to migrate; the besiegers guaranteed a safe passage but Guru Gobind Singh did not trust them.[3] The Sikhs eventually left Anandapur in the night and took refuge in Chamkaur, only for its Hindu Zamindar to inform the Rajahs and Mughal authority.[4] In the melee that ensued, Singh escaped but most of his men were either killed or captured.[4]

Death

[edit]

Some Sikh accounts note Singh's two younger sons — Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh — to have successfully fought at Chamkaur before being captured.[4] Other accounts note that they along with their grandmother had been separated from the Sikh retinue while migrating away from Anandapur; subsequently, they were betrayed by local officials and handed over to the Mughals.[4] Sukha Singh and Ratan Singh Bhangu, in particular, blame a greedy Brahmin for the betrayal.[4]

The sons were taken to Sirhind and coerced for conversion to Islam in the court of Wazir Khan, the provincial governor.[4] Sikh accounts accuse Sucha Nand, the Hindu Diwan, to have been the most vocal advocate for executing the children; Sher Muhammad Khan, the Nawab of Meherkotla, despite being an ally of the Mughals and losing relatives in the faceoff, was the sole dissenter.[4][5] Both of the children maintained a steadfast refusal to convert and were executed.[4] In early Sikh accounts, they were simply beheaded; in popular Sikh tradition, they are held to have been "bricked" (entombed) alive.[6]

Legacy

[edit]Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has paid homage to the Chaar Sahibzaade on various occasions, particularly during the celebration of their bravery and sacrifice on Veer Bal Diwas (Day of Brave Children). Veer Bal Diwas is observed in honour of the Chaar Sahibzaade.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harbans Singh, ed. (1992–1998). The encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Vol. 4. Patiala: Punjabi University. p. 461. ISBN 0-8364-2883-8. OCLC 29703420.

- ^ "The Sikh Review". The Sikh Review. 69: 06 (810): 82. 1 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Grewal, J. S. (2020). "Ouster from Anandpur (1699–1704)". Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708): Master of the White Hawk. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199494941.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grewal, J. S. (2020). "Negotiations with Aurangzeb (1705–7)". Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708): Master of the White Hawk. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199494941.

- ^ Bigelow, Anna (2010). "The Nawabs: Good, Bad, and Ugly". Sharing the Sacred: Practicing Pluralism in Muslim North India. Oxford University Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-0-19-536823-9.

- ^ Fenech, Louis E. (2013). "Ẓafar-Nāmah, Fatḥ-Nāmah, Ḥikāyats, and the Dasam Granth". The Sikh Ẓafar-nāmah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780199931439.

- ^ "Veer Bal Diwas 2022: History, significance and everything you need to know". India Today.