Adderall

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| |

| |

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| amphetamine aspartate monohydrate | 25% – stimulant (12.5% levo; 12.5% dextro) |

| amphetamine sulfate | 25% – stimulant (12.5% levo; 12.5% dextro) |

| dextroamphetamine saccharate | 25% – stimulant (0% levo; 25% dextro) |

| dextroamphetamine sulfate | 25% – stimulant (0% levo; 25% dextro) |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Adderall, Adderall XR, Mydayis |

| Other names | Mixed amphetamine salts; MAS |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601234 |

| License data | |

| Dependence liability | Moderate[3][4] – high[5][6][7] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, insufflation, rectal, sublingual |

| Drug class | CNS stimulant |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: ~90%[9] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| (verify) | |

Adderall and Mydayis[10] are trade names[note 2] for a combination drug called mixed amphetamine salts containing four salts of amphetamine. The mixture is composed of equal parts racemic amphetamine and dextroamphetamine, which produces a (3:1) ratio between dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine, the two enantiomers of amphetamine. Both enantiomers are stimulants, but differ enough to give Adderall an effects profile distinct from those of racemic amphetamine or dextroamphetamine,[1][2] which are marketed as Evekeo and Dexedrine/Zenzedi, respectively.[1][12][13] Adderall is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. It is also used illicitly as an athletic performance enhancer, cognitive enhancer, appetite suppressant, and recreationally as a euphoriant. It is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the phenethylamine class.[1]

Adderall is generally well-tolerated and effective in treating symptoms of ADHD and narcolepsy. At therapeutic doses, Adderall causes emotional and cognitive effects such as euphoria, change in sex drive, increased wakefulness, and improved cognitive control. At these doses, it induces physical effects such as a faster reaction time, fatigue resistance, and increased muscle strength. In contrast, much larger doses of Adderall can impair cognitive control, cause rapid muscle breakdown, provoke panic attacks, or induce a psychosis (e.g., paranoia, delusions, hallucinations). The side effects of Adderall vary widely among individuals, but most commonly include insomnia, dry mouth, loss of appetite, and weight loss. The risk of developing an addiction or dependence is insignificant when Adderall is used as prescribed at fairly low daily doses, such as those used for treating ADHD; however, the routine use of Adderall in larger daily doses poses a significant risk of addiction or dependence due to the pronounced reinforcing effects that are present at high doses. Recreational doses of amphetamine are generally much larger than prescribed therapeutic doses, and carry a far greater risk of serious adverse effects.[sources 1]

The two amphetamine enantiomers that compose Adderall (levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine) alleviate the symptoms of ADHD and narcolepsy by increasing the activity of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and dopamine in the brain, which results in part from their interactions with human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (hTAAR1) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) in neurons. Dextroamphetamine is a more potent Central nervous system (CNS) stimulant than levoamphetamine, but levoamphetamine has slightly stronger cardiovascular and peripheral effects and a longer elimination half-life than dextroamphetamine. The levoamphetamine component of Adderall has been reported to improve the treatment response in some individuals relative to dextroamphetamine alone. Adderall's active ingredient, amphetamine, shares many chemical and pharmacological properties with the human trace amines, particularly phenethylamine and N-methylphenethylamine, the latter of which is a positional isomer of amphetamine.[sources 2] In 2021, Adderall was the seventeenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 30 million prescriptions.[33][34]

Uses[edit]

Medical[edit]

Adderall is commonly used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy (a sleep disorder).[35][15] Long-term amphetamine exposure at sufficiently high doses in some animal species is known to produce abnormal dopamine system development or nerve damage,[36][37] but, in humans with ADHD, long-term use of pharmaceutical amphetamines at therapeutic doses appears to improve brain development and nerve growth.[38][39][40] Reviews of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD, and improves function in several parts of the brain, such as the right caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia.[38][39][40]

Reviews of clinical stimulant research have established the safety and effectiveness of long-term continuous amphetamine use for the treatment of ADHD.[41][42][43] Randomized controlled trials of continuous stimulant therapy for the treatment of ADHD spanning 2 years have demonstrated treatment effectiveness and safety.[41][42] Two reviews have indicated that long-term continuous stimulant therapy for ADHD is effective for reducing the core symptoms of ADHD (i.e., hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity), enhancing quality of life and academic achievement, and producing improvements in a large number of functional outcomes[note 3] across 9 categories of outcomes related to academics, antisocial behavior, driving, non-medicinal drug use, obesity, occupation, self-esteem, service use (i.e., academic, occupational, health, financial, and legal services), and social function.[41][43] One review highlighted a nine-month randomized controlled trial of amphetamine treatment for ADHD in children that found an average increase of 4.5 IQ points, continued increases in attention, and continued decreases in disruptive behaviors and hyperactivity.[42] Another review indicated that, based upon the longest follow-up studies conducted to date, lifetime stimulant therapy that begins during childhood is continuously effective for controlling ADHD symptoms and reduces the risk of developing a substance use disorder as an adult.[41]

Current models of ADHD suggest that it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems;[44] these functional impairments involve impaired dopamine neurotransmission in the mesocorticolimbic projection and norepinephrine neurotransmission in the noradrenergic projections from the locus coeruleus to the prefrontal cortex.[44] Psychostimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamine are effective in treating ADHD because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems.[16][44][45] Approximately 80% of those who use these stimulants see improvements in ADHD symptoms.[46] Children with ADHD who use stimulant medications generally have better relationships with peers and family members, perform better in school, are less distractible and impulsive, and have longer attention spans.[47][48] The Cochrane reviews[note 4] on the treatment of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults with pharmaceutical amphetamines stated that short-term studies have demonstrated that these drugs decrease the severity of symptoms, but they have higher discontinuation rates than non-stimulant medications due to their adverse side effects.[50][51] A Cochrane review on the treatment of ADHD in children with tic disorders such as Tourette syndrome indicated that stimulants in general do not make tics worse, but high doses of dextroamphetamine could exacerbate tics in some individuals.[52]

Available forms[edit]

Adderall is available as immediate-release (IR) tablets and extended-release (XR) capsules.[15][53] Mydayis is only available in an extended-release formulation.[54] Adderall XR is approved to treat ADHD for up to 12 hours in individuals 6 years and older and uses a double-bead formulation. The capsule can be swallowed like a tablet, or it can be opened and the beads sprinkled over applesauce for comparable absorption.[53] Upon ingestion, half of the beads provide immediate administration of medication, while the other half are enveloped in a coating which must dissolve, delaying absorption of its contents. It is designed to provide a therapeutic effect and plasma concentrations identical to taking two doses of Adderall IR four hours apart.[53] Mydayis uses a longer-lasting triple-bead formulation and is approved to treat ADHD for up to 16 hours in individuals 13 years and older.[54] In the United States, the immediate and extended-release formulations of Adderall are both available as generic drugs.[55][56] Generic formulations of Mydayis became available in the US in October 2023.[57]

Enhancing performance[edit]

Cognitive performance[edit]

In 2015, a systematic review and a meta-analysis of high quality clinical trials found that, when used at low (therapeutic) doses, amphetamine produces modest yet unambiguous improvements in cognition, including working memory, long-term episodic memory, inhibitory control, and some aspects of attention, in normal healthy adults;[58][59] these cognition-enhancing effects of amphetamine are known to be partially mediated through the indirect activation of both dopamine receptor D1 and adrenoceptor α2 in the prefrontal cortex.[16][58] A systematic review from 2014 found that low doses of amphetamine also improve memory consolidation, in turn leading to improved recall of information.[60] Therapeutic doses of amphetamine also enhance cortical network efficiency, an effect which mediates improvements in working memory in all individuals.[16][61] Amphetamine and other ADHD stimulants also improve task saliency (motivation to perform a task) and increase arousal (wakefulness), in turn promoting goal-directed behavior.[16][62][63] Stimulants such as amphetamine can improve performance on difficult and boring tasks and are used by some students as a study and test-taking aid.[16][63][64] Based upon studies of self-reported illicit stimulant use, 5–35% of college students use diverted ADHD stimulants, which are primarily used for enhancement of academic performance rather than as recreational drugs.[65][66][67] However, high amphetamine doses that are above the therapeutic range can interfere with working memory and other aspects of cognitive control.[16][63]

Physical performance[edit]

Amphetamine is used by some athletes for its psychological and athletic performance-enhancing effects, such as increased endurance and alertness;[17][29] however, non-medical amphetamine use is prohibited at sporting events that are regulated by collegiate, national, and international anti-doping agencies.[68][69] In healthy people at oral therapeutic doses, amphetamine has been shown to increase muscle strength, acceleration, athletic performance in anaerobic conditions, and endurance (i.e., it delays the onset of fatigue), while improving reaction time.[17][70][71] Amphetamine improves endurance and reaction time primarily through reuptake inhibition and release of dopamine in the central nervous system.[70][71][72] Amphetamine and other dopaminergic drugs also increase power output at fixed levels of perceived exertion by overriding a "safety switch", allowing the core temperature limit to increase in order to access a reserve capacity that is normally off-limits.[71][73][74] At therapeutic doses, the adverse effects of amphetamine do not impede athletic performance;[17][70] however, at much higher doses, amphetamine can induce effects that severely impair performance, such as rapid muscle breakdown and elevated body temperature.[18][70]

Adderall has been banned in the National Football League (NFL), Major League Baseball (MLB), National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA).[75] In leagues such as the NFL, there is a very rigorous process required to obtain an exemption to this rule even when the athlete has been medically prescribed the drug by their physician.[75]

Recreational[edit]

Adderall has high potential for misuse as a recreational drug.[76][77][78] Adderall tablets can either be swallowed, crushed and snorted, or dissolved in water and injected.[79] Injection into the bloodstream can be dangerous because insoluble fillers within the tablets can block small blood vessels.[79]

Many postsecondary students have reported using Adderall for study purposes in different parts of the developed world.[78] Among these students, some of the risk factors for misusing ADHD stimulants recreationally include: possessing deviant personality characteristics (i.e., exhibiting delinquent or deviant behavior), inadequate accommodation of disability, basing one's self-worth on external validation, low self-efficacy, earning poor grades, and having an untreated mental health disorder.[78]

Contraindications[edit]

Adverse effects[edit]

The adverse side effects of Adderall are many and varied, but the amount of substance consumed is the primary factor in determining the likelihood and severity of side effects.[18][29] Adderall is currently approved for long-term therapeutic use by the USFDA.[18] Recreational use of Adderall generally involves far larger doses and is therefore significantly more dangerous, involving a much greater risk of serious adverse drug effects than dosages used for therapeutic purposes.[29]

Physical[edit]

Cardiovascular side effects can include hypertension or hypotension from a vasovagal response, Raynaud's phenomenon (reduced blood flow to the hands and feet), and tachycardia (increased heart rate).[18][29][90] Sexual side effects in males may include erectile dysfunction, frequent erections, or prolonged erections.[18] Gastrointestinal side effects may include abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, and nausea.[7][18][91] Other potential physical side effects include appetite loss, blurred vision, dry mouth, excessive grinding of the teeth, nosebleed, profuse sweating, rhinitis medicamentosa (drug-induced nasal congestion), reduced seizure threshold, tics (a type of movement disorder), and weight loss.[sources 3] Dangerous physical side effects are rare at typical pharmaceutical doses.[29]

Amphetamine stimulates the medullary respiratory centers, producing faster and deeper breaths.[29] In a normal person at therapeutic doses, this effect is usually not noticeable, but when respiration is already compromised, it may be evident.[29] Amphetamine also induces contraction in the urinary bladder sphincter, the muscle which controls urination, which can result in difficulty urinating.[29] This effect can be useful in treating bed wetting and loss of bladder control.[29] The effects of amphetamine on the gastrointestinal tract are unpredictable.[29] If intestinal activity is high, amphetamine may reduce gastrointestinal motility (the rate at which content moves through the digestive system);[29] however, amphetamine may increase motility when the smooth muscle of the tract is relaxed.[29] Amphetamine also has a slight analgesic effect and can enhance the pain relieving effects of opioids.[7][29]

USFDA-commissioned studies from 2011 indicate that in children, young adults, and adults there is no association between serious adverse cardiovascular events (sudden death, heart attack, and stroke) and the medical use of amphetamine or other ADHD stimulants.[sources 4] However, amphetamine pharmaceuticals are contraindicated in individuals with cardiovascular disease.[sources 5]

Psychological[edit]

At normal therapeutic doses, the most common psychological side effects of amphetamine include increased alertness, apprehension, concentration, initiative, self-confidence and sociability, mood swings (elated mood followed by mildly depressed mood), insomnia or wakefulness, and decreased sense of fatigue.[18][29] Less common side effects include anxiety, change in libido, grandiosity, irritability, repetitive or obsessive behaviors, and restlessness;[sources 6] these effects depend on the user's personality and current mental state.[29] Amphetamine psychosis (e.g., delusions and paranoia) can occur in heavy users.[18][19][99] Although very rare, this psychosis can also occur at therapeutic doses during long-term therapy.[18][99][20] According to the USFDA, "there is no systematic evidence" that stimulants produce aggressive behavior or hostility.[18]

Amphetamine has also been shown to produce a conditioned place preference in humans taking therapeutic doses,[50][100] meaning that individuals acquire a preference for spending time in places where they have previously used amphetamine.[100][101]

Reinforcement disorders[edit]

Addiction[edit]

| Addiction and dependence glossary[101][102][103] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Transcription factor glossary | |

|---|---|

| |

Addiction is a serious risk with heavy recreational amphetamine use, but is unlikely to occur from long-term medical use at therapeutic doses;[41][21][22] in fact, lifetime stimulant therapy for ADHD that begins during childhood reduces the risk of developing substance use disorders as an adult.[41] Pathological overactivation of the mesolimbic pathway, a dopamine pathway that connects the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens, plays a central role in amphetamine addiction.[111][112] Individuals who frequently self-administer high doses of amphetamine have a high risk of developing an amphetamine addiction, since chronic use at high doses gradually increases the level of accumbal ΔFosB, a "molecular switch" and "master control protein" for addiction.[102][113][114] Once nucleus accumbens ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it begins to increase the severity of addictive behavior (i.e., compulsive drug-seeking) with further increases in its expression.[113][115] While there are currently no effective drugs for treating amphetamine addiction, regularly engaging in sustained aerobic exercise appears to reduce the risk of developing such an addiction.[116][117] Exercise therapy improves clinical treatment outcomes and may be used as an adjunct therapy with behavioral therapies for addiction.[116][118][sources 7]

Biomolecular mechanisms[edit]

Chronic use of amphetamine at excessive doses causes alterations in gene expression in the mesocorticolimbic projection, which arise through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms.[114][119][120] The most important transcription factors[note 8] that produce these alterations are Delta FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (ΔFosB), cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB).[114] ΔFosB is the most significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction because ΔFosB overexpression (i.e., an abnormally high level of gene expression which produces a pronounced gene-related phenotype) in the D1-type medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient[note 9] for many of the neural adaptations and regulates multiple behavioral effects (e.g., reward sensitization and escalating drug self-administration) involved in addiction.[102][113][114] Once ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it induces an addictive state that becomes increasingly more severe with further increases in ΔFosB expression.[102][113] It has been implicated in addictions to alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine, propofol, and substituted amphetamines, among others.[sources 8]

ΔJunD, a transcription factor, and G9a, a histone methyltransferase enzyme, both oppose the function of ΔFosB and inhibit increases in its expression.[102][114][124] Sufficiently overexpressing ΔJunD in the nucleus accumbens with viral vectors can completely block many of the neural and behavioral alterations seen in chronic drug abuse (i.e., the alterations mediated by ΔFosB).[114] Similarly, accumbal G9a hyperexpression results in markedly increased histone 3 lysine residue 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2) and blocks the induction of ΔFosB-mediated neural and behavioral plasticity by chronic drug use,[sources 9] which occurs via H3K9me2-mediated repression of transcription factors for ΔFosB and H3K9me2-mediated repression of various ΔFosB transcriptional targets (e.g., CDK5).[114][124][125] ΔFosB also plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise.[115][114][128] Since both natural rewards and addictive drugs induce the expression of ΔFosB (i.e., they cause the brain to produce more of it), chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological state of addiction.[115][114] Consequently, ΔFosB is the most significant factor involved in both amphetamine addiction and amphetamine-induced sexual addictions, which are compulsive sexual behaviors that result from excessive sexual activity and amphetamine use.[115][129][130] These sexual addictions are associated with a dopamine dysregulation syndrome which occurs in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs.[115][128]

The effects of amphetamine on gene regulation are both dose- and route-dependent.[120] Most of the research on gene regulation and addiction is based upon animal studies with intravenous amphetamine administration at very high doses.[120] The few studies that have used equivalent (weight-adjusted) human therapeutic doses and oral administration show that these changes, if they occur, are relatively minor.[120] This suggests that medical use of amphetamine does not significantly affect gene regulation.[120]

Pharmacological treatments[edit]

As of December 2019,[update] there is no effective pharmacotherapy for amphetamine addiction.[131][132][133] Reviews from 2015 and 2016 indicated that TAAR1-selective agonists have significant therapeutic potential as a treatment for psychostimulant addictions;[134][135] however, as of February 2016,[update] the only compounds which are known to function as TAAR1-selective agonists are experimental drugs.[134][135] Amphetamine addiction is largely mediated through increased activation of dopamine receptors and co-localized NMDA receptors[note 10] in the nucleus accumbens;[112] magnesium ions inhibit NMDA receptors by blocking the receptor calcium channel.[112][136] One review suggested that, based upon animal testing, pathological (addiction-inducing) psychostimulant use significantly reduces the level of intracellular magnesium throughout the brain.[112] Supplemental magnesium[note 11] treatment has been shown to reduce amphetamine self-administration (i.e., doses given to oneself) in humans, but it is not an effective monotherapy for amphetamine addiction.[112]

A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2019 assessed the efficacy of 17 different pharmacotherapies used in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for amphetamine and methamphetamine addiction;[132] it found only low-strength evidence that methylphenidate might reduce amphetamine or methamphetamine self-administration.[132] There was low- to moderate-strength evidence of no benefit for most of the other medications used in RCTs, which included antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, sertraline), antipsychotics (aripiprazole), anticonvulsants (topiramate, baclofen, gabapentin), naltrexone, varenicline, citicoline, ondansetron, prometa, riluzole, atomoxetine, dextroamphetamine, and modafinil.[132]

Behavioral treatments[edit]

A 2018 systematic review and network meta-analysis of 50 trials involving 12 different psychosocial interventions for amphetamine, methamphetamine, or cocaine addiction found that combination therapy with both contingency management and community reinforcement approach had the highest efficacy (i.e., abstinence rate) and acceptability (i.e., lowest dropout rate).[137] Other treatment modalities examined in the analysis included monotherapy with contingency management or community reinforcement approach, cognitive behavioral therapy, 12-step programs, non-contingent reward-based therapies, psychodynamic therapy, and other combination therapies involving these.[137]

Additionally, research on the neurobiological effects of physical exercise suggests that daily aerobic exercise, especially endurance exercise (e.g., marathon running), prevents the development of drug addiction and is an effective adjunct therapy (i.e., a supplemental treatment) for amphetamine addiction.[sources 7] Exercise leads to better treatment outcomes when used as an adjunct treatment, particularly for psychostimulant addictions.[116][118][138] In particular, aerobic exercise decreases psychostimulant self-administration, reduces the reinstatement (i.e., relapse) of drug-seeking, and induces increased dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) density in the striatum.[115][138] This is the opposite of pathological stimulant use, which induces decreased striatal DRD2 density.[115] One review noted that exercise may also prevent the development of a drug addiction by altering ΔFosB or c-Fos immunoreactivity in the striatum or other parts of the reward system.[117]

| Form of neuroplasticity or behavioral plasticity | Type of reinforcer | Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opiates | Psychostimulants | High fat or sugar food | Sexual intercourse | Physical exercise (aerobic) | Environmental enrichment | ||

| ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type MSNs | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [115] |

| Behavioral plasticity | |||||||

| Escalation of intake | Yes | Yes | Yes | [115] | |||

| Psychostimulant cross-sensitization | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Attenuated | Attenuated | [115] |

| Psychostimulant self-administration | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [115] | |

| Psychostimulant conditioned place preference | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [115] |

| Reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [115] | ||

| Neurochemical plasticity | |||||||

| CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [115] | |

| Sensitized dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens | No | Yes | No | Yes | [115] | ||

| Altered striatal dopamine signaling | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [115] | |

| Altered striatal opioid signaling | No change or ↑μ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors ↑κ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors | No change | No change | [115] |

| Changes in striatal opioid peptides | ↑dynorphin No change: enkephalin | ↑dynorphin | ↓enkephalin | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | [115] | |

| Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity | |||||||

| Number of dendrites in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [115] | |||

| Dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [115] | |||

Dependence and withdrawal[edit]

Drug tolerance develops rapidly in amphetamine abuse (i.e., recreational amphetamine use), so periods of extended abuse require increasingly larger doses of the drug in order to achieve the same effect.[139][140] According to a Cochrane review on withdrawal in individuals who compulsively use amphetamine and methamphetamine, "when chronic heavy users abruptly discontinue amphetamine use, many report a time-limited withdrawal syndrome that occurs within 24 hours of their last dose."[141] This review noted that withdrawal symptoms in chronic, high-dose users are frequent, occurring in roughly 88% of cases, and persist for 3–4 weeks with a marked "crash" phase occurring during the first week.[141] Amphetamine withdrawal symptoms can include anxiety, drug craving, depressed mood, fatigue, increased appetite, increased movement or decreased movement, lack of motivation, sleeplessness or sleepiness, and lucid dreams.[141] The review indicated that the severity of withdrawal symptoms is positively correlated with the age of the individual and the extent of their dependence.[141] Mild withdrawal symptoms from the discontinuation of amphetamine treatment at therapeutic doses can be avoided by tapering the dose.[7]

Overdose[edit]

An amphetamine overdose can lead to many different symptoms, but is rarely fatal with appropriate care.[142][84][143] The severity of overdose symptoms increases with dosage and decreases with drug tolerance to amphetamine.[144][84] Tolerant individuals have been known to take as much as 5 grams of amphetamine in a day, which is roughly 100 times the maximum daily therapeutic dose.[84] Symptoms of a moderate and extremely large overdose are listed below; fatal amphetamine poisoning usually also involves convulsions and coma.[83][144] In 2013, overdose on amphetamine, methamphetamine, and other compounds implicated in an "amphetamine use disorder" resulted in an estimated 3,788 deaths worldwide (3,425–4,145 deaths, 95% confidence).[note 12][145]

| System | Minor or moderate overdose[83][144][84] | Severe overdose[sources 10] |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

| |

| Central nervous system |

|

|

| Musculoskeletal |

| |

| Respiratory |

|

|

| Urinary |

| |

| Other |

|

|

Interactions[edit]

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) taken with amphetamine may result in a hypertensive crisis if taken within two weeks after last use of an MAOI type drug.[148]

- Inhibitors of enzymes that directly metabolize amphetamine (particularly CYP2D6 and FMO3) will prolong the elimination of amphetamine and increase drug effects.[148][149][150]

- Serotonergic drugs (such as most antidepressants) co-administered with amphetamine increases the risk of serotonin syndrome.[150]

- Stimulants and antidepressants (sedatives and depressants) may increase (decrease) the drug effects of amphetamine, and vice versa.[148]

- Gastrointestinal and urinary pH affect the absorption and elimination of amphetamine, respectively. Gastrointestinal alkalinizing agents increase the absorption of amphetamine. Urinary alkalinizing agents increase concentration of non-ionized species, decreasing urinary excretion.[148]

- Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) modify the absorption of Adderall XR and Mydayis.[148][150]

- Zinc supplementation may reduce the minimum effective dose of amphetamine when it is used for the treatment of ADHD.[note 13][154]

Pharmacology[edit]

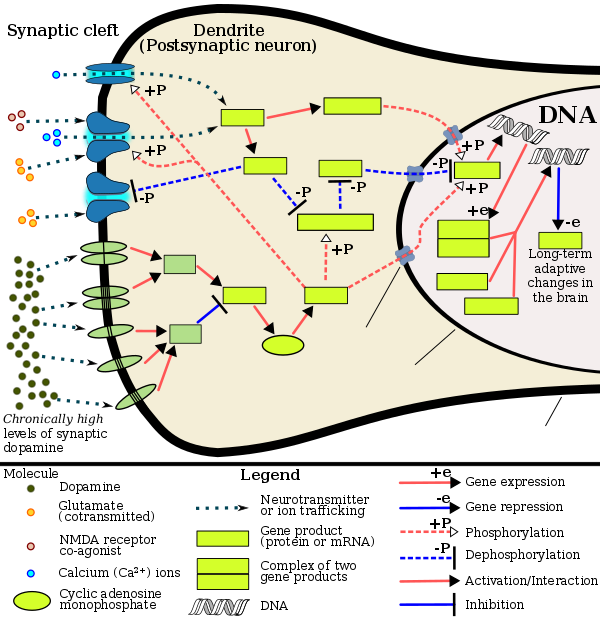

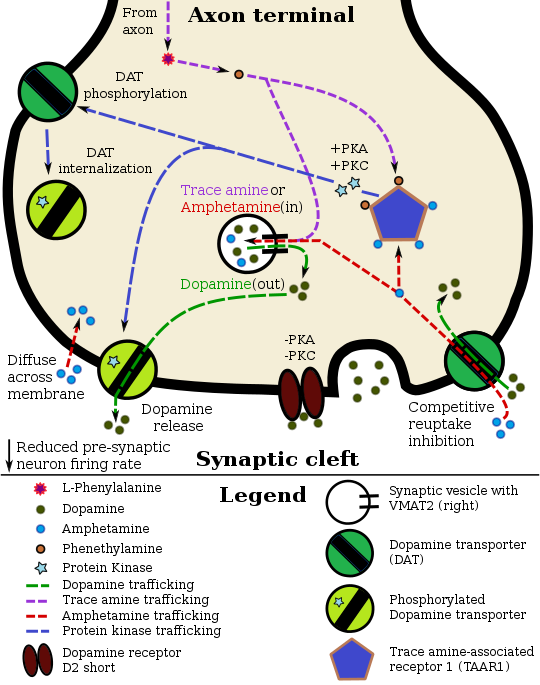

Pharmacodynamics of amphetamine in a dopamine neuron |

Mechanism of action[edit]

Amphetamine, the active ingredient of Adderall, works primarily by increasing the activity of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain.[25][45] It also triggers the release of several other hormones (e.g., epinephrine) and neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin and histamine) as well as the synthesis of certain neuropeptides (e.g., cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) peptides).[27][160] Both active ingredients of Adderall, dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine, bind to the same biological targets,[29][30] but their binding affinities (that is, potency) differ somewhat.[29][30] Dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine are both potent full agonists (activating compounds) of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and interact with vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), with dextroamphetamine being the more potent agonist of TAAR1.[30] Consequently, dextroamphetamine produces more CNS stimulation than levoamphetamine;[30][161] however, levoamphetamine has slightly greater cardiovascular and peripheral effects.[29] It has been reported that certain children have a better clinical response to levoamphetamine.[31][32]

In the absence of amphetamine, VMAT2 will normally move monoamines (e.g., dopamine, histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, etc.) from the intracellular fluid of a monoamine neuron into its synaptic vesicles, which store neurotransmitters for later release (via exocytosis) into the synaptic cleft.[27] When amphetamine enters a neuron and interacts with VMAT2, the transporter reverses its direction of transport, thereby releasing stored monoamines inside synaptic vesicles back into the neuron's intracellular fluid.[27] Meanwhile, when amphetamine activates TAAR1, the receptor causes the neuron's cell membrane-bound monoamine transporters (i.e., the dopamine transporter, norepinephrine transporter, or serotonin transporter) to either stop transporting monoamines altogether (via transporter internalization) or transport monoamines out of the neuron;[26] in other words, the reversed membrane transporter will push dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin out of the neuron's intracellular fluid and into the synaptic cleft.[26] In summary, by interacting with both VMAT2 and TAAR1, amphetamine releases neurotransmitters from synaptic vesicles (the effect from VMAT2) into the intracellular fluid where they subsequently exit the neuron through the membrane-bound, reversed monoamine transporters (the effect from TAAR1).[26][27]

Pharmacokinetics[edit]

The oral bioavailability of amphetamine varies with gastrointestinal pH;[18] it is well absorbed from the gut, and bioavailability is typically 90%.[9] Amphetamine is a weak base with a pKa of 9.9;[162] consequently, when the pH is basic, more of the drug is in its lipid soluble free base form, and more is absorbed through the lipid-rich cell membranes of the gut epithelium.[162][18] Conversely, an acidic pH means the drug is predominantly in a water-soluble cationic (salt) form, and less is absorbed.[162] Approximately 20% of amphetamine circulating in the bloodstream is bound to plasma proteins.[163] Following absorption, amphetamine readily distributes into most tissues in the body, with high concentrations occurring in cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue.[164]

The half-lives of amphetamine enantiomers differ and vary with urine pH.[162] At normal urine pH, the half-lives of dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine are 9–11 hours and 11–14 hours, respectively.[162] Highly acidic urine will reduce the enantiomer half-lives to 7 hours;[164] highly alkaline urine will increase the half-lives up to 34 hours.[164] The immediate-release and extended release variants of salts of both isomers reach peak plasma concentrations at 3 hours and 7 hours post-dose respectively.[162] Amphetamine is eliminated via the kidneys, with 30–40% of the drug being excreted unchanged at normal urinary pH.[162] When the urinary pH is basic, amphetamine is in its free base form, so less is excreted.[162] When urine pH is abnormal, the urinary recovery of amphetamine may range from a low of 1% to a high of 75%, depending mostly upon whether urine is too basic or acidic, respectively.[162] Following oral administration, amphetamine appears in urine within 3 hours.[164] Roughly 90% of ingested amphetamine is eliminated 3 days after the last oral dose.[164]

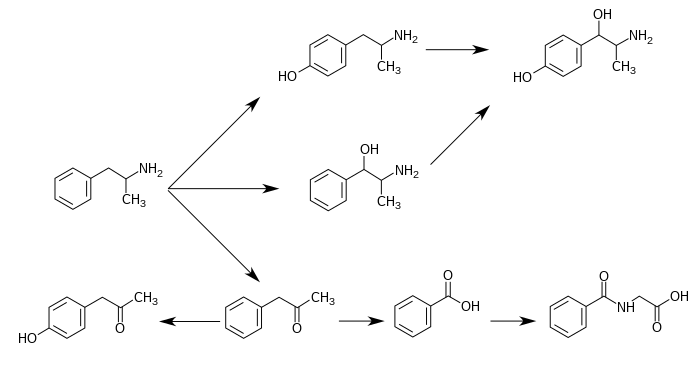

CYP2D6, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3), butyrate-CoA ligase (XM-ligase), and glycine N-acyltransferase (GLYAT) are the enzymes known to metabolize amphetamine or its metabolites in humans.[sources 11] Amphetamine has a variety of excreted metabolic products, including 4-hydroxyamphetamine, 4-hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetone, benzoic acid, hippuric acid, norephedrine, and phenylacetone.[162][165] Among these metabolites, the active sympathomimetics are 4-hydroxyamphetamine,[166] 4-hydroxynorephedrine,[167] and norephedrine.[168] The main metabolic pathways involve aromatic para-hydroxylation, aliphatic alpha- and beta-hydroxylation, N-oxidation, N-dealkylation, and deamination.[162][169] The known metabolic pathways, detectable metabolites, and metabolizing enzymes in humans include the following:

Metabolic pathways of amphetamine in humans[sources 11] |

Pharmacomicrobiomics[edit]

The human metagenome (i.e., the genetic composition of an individual and all microorganisms that reside on or within the individual's body) varies considerably between individuals.[178][179] Since the total number of microbial and viral cells in the human body (over 100 trillion) greatly outnumbers human cells (tens of trillions),[note 15][178][180] there is considerable potential for interactions between drugs and an individual's microbiome, including: drugs altering the composition of the human microbiome, drug metabolism by microbial enzymes modifying the drug's pharmacokinetic profile, and microbial drug metabolism affecting a drug's clinical efficacy and toxicity profile.[178][179][181] The field that studies these interactions is known as pharmacomicrobiomics.[178]

Similar to most biomolecules and other orally administered xenobiotics (i.e., drugs), amphetamine is predicted to undergo promiscuous metabolism by human gastrointestinal microbiota (primarily bacteria) prior to absorption into the blood stream.[181] The first amphetamine-metabolizing microbial enzyme, tyramine oxidase from a strain of E. coli commonly found in the human gut, was identified in 2019.[181] This enzyme was found to metabolize amphetamine, tyramine, and phenethylamine with roughly the same binding affinity for all three compounds.[181]Related endogenous compounds[edit]

Amphetamine has a very similar structure and function to the endogenous trace amines, which are naturally occurring neuromodulator molecules produced in the human body and brain.[26][182][183] Among this group, the most closely related compounds are phenethylamine, the parent compound of amphetamine, and N-methylphenethylamine, a structural isomer of amphetamine (i.e., it has an identical molecular formula).[26][182][184] In humans, phenethylamine is produced directly from L-phenylalanine by the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) enzyme, which converts L-DOPA into dopamine as well.[182][184] In turn, N-methylphenethylamine is metabolized from phenethylamine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, the same enzyme that metabolizes norepinephrine into epinephrine.[182][184] Like amphetamine, both phenethylamine and N-methylphenethylamine regulate monoamine neurotransmission via TAAR1;[26][183][184] unlike amphetamine, both of these substances are broken down by monoamine oxidase B, and therefore have a shorter half-life than amphetamine.[182][184]

History[edit]

The pharmaceutical company Rexar reformulated their popular weight loss drug Obetrol following its mandatory withdrawal from the market in 1973 under the Kefauver Harris Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act due to the results of the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) program (which indicated a lack of efficacy). The new formulation simply replaced the two methamphetamine components with dextroamphetamine and amphetamine components of the same weight (the other two original dextroamphetamine and amphetamine components were preserved), preserved the Obetrol branding, and despite it lacking FDA approval, it still made it onto the market and was marketed and sold by Rexar for many years.

In 1994, Richwood Pharmaceuticals acquired Rexar and began promoting Obetrol as a treatment for ADHD (and later narcolepsy as well), now marketed under the new brand name of Adderall, a contraction of the phrase "A.D.D. for All" intended to convey that "it was meant to be kind of an inclusive thing" for marketing purposes.[185] The FDA cited the company for numerous significant CGMP violations related to Obetrol discovered during routine inspections following the acquisition (including issuing a formal warning letter for the violations), then later issued a second formal warning letter to Richwood Pharmaceuticals specifically due to violations of "the new drug and misbranding provisions of the FD&C Act". Following extended discussions with Richwood Pharmaceuticals regarding the resolution of a large number of issues related to the company's numerous violations of FDA regulations, the FDA formally approved the first Obetrol labeling/sNDA revisions in 1996, including a name change to Adderall and a restoration of its status as an approved drug product.[186][187] In 1997 Richwood Pharmaceuticals was acquired by Shire Pharmaceuticals in a $186 million transaction.[185]

Richwood Pharmaceuticals, which later merged with Shire plc, introduced the current Adderall brand in 1996 as an instant-release tablet.[188] In 2006, Shire agreed to sell rights to the Adderall name for the instant-release form of the medication to Duramed Pharmaceuticals.[189] DuraMed Pharmaceuticals was acquired by Teva Pharmaceuticals in 2008 during their acquisition of Barr Pharmaceuticals, including Barr's Duramed division.[190]

The first generic version of Adderall IR was introduced to market in 2002.[11] Later on, Barr and Shire reached a settlement agreement permitting Barr to offer a generic form of the extended-release drug beginning in April 2009.[11][191]

Commercial formulation[edit]

Chemically, Adderall is a mixture of four amphetamine salts; specifically, it is composed of equal parts (by mass) of amphetamine aspartate monohydrate, amphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine sulfate, and dextroamphetamine saccharate.[53] This drug mixture has slightly stronger CNS effects than racemic amphetamine due to the higher proportion of dextroamphetamine.[26][29] Adderall is produced as both an immediate-release (IR) and extended-release (XR) formulation.[11][15][53] As of December 2013[update], ten different companies produced generic Adderall IR, while Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Actavis, and Barr Pharmaceuticals manufactured generic Adderall XR.[11] As of 2013[update], Shire plc, the company that held the original patent for Adderall and Adderall XR, still manufactured brand name Adderall XR, but not Adderall IR.[11]

Comparison to other formulations[edit]

Adderall is one of several formulations of pharmaceutical amphetamine, including singular or mixed enantiomers and as an enantiomer prodrug. The table below compares these medications (based on U.S.-approved forms):

| drug | formula | molar mass [note 16] | amphetamine base [note 17] | amphetamine base in equal doses | doses with equal base content [note 18] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/mol) | (percent) | (30 mg dose) | ||||||||

| total | base | total | dextro- | levo- | dextro- | levo- | ||||

| dextroamphetamine sulfate[193][194] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 73.38% | — | 22.0 mg | — | 30.0 mg | |

| amphetamine sulfate[195] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 36.69% | 36.69% | 11.0 mg | 11.0 mg | 30.0 mg | |

| Adderall | 62.57% | 47.49% | 15.08% | 14.2 mg | 4.5 mg | 35.2 mg | ||||

| 25% | dextroamphetamine sulfate[193][194] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 73.38% | — | |||

| 25% | amphetamine sulfate[195] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49 | 270.41 | 73.38% | 36.69% | 36.69% | |||

| 25% | dextroamphetamine saccharate[196] | (C9H13N)2•C6H10O8 | 480.55 | 270.41 | 56.27% | 56.27% | — | |||

| 25% | amphetamine aspartate monohydrate[197] | (C9H13N)•C4H7NO4•H2O | 286.32 | 135.21 | 47.22% | 23.61% | 23.61% | |||

| lisdexamfetamine dimesylate[198] | C15H25N3O•(CH4O3S)2 | 455.49 | 135.21 | 29.68% | 29.68% | — | 8.9 mg | — | 74.2 mg | |

| amphetamine base suspension[91] | C9H13N | 135.21 | 135.21 | 100% | 76.19% | 23.81% | 22.9 mg | 7.1 mg | 22.0 mg | |

Society and culture[edit]

Legal status[edit]

- In Canada, amphetamines are in Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, and can only be obtained by prescription.[199]

- In Japan, the use, production, and import of any medicine containing amphetamines is prohibited.[200]

- In South Korea, amphetamines are prohibited.[201]

- In Taiwan, amphetamines including Adderall are Schedule 2 drugs with a minimum five years prison term for possession.[202] Only Ritalin can be legally prescribed for treatment of ADHD [citation needed].

- In Thailand, amphetamines are classified as Type 1 Narcotics.[203]

- In the United Kingdom, amphetamines are regarded as Class B drugs. The maximum penalty for unauthorized possession is five years in prison and an unlimited fine. The maximum penalty for illegal supply is 14 years in prison and an unlimited fine.[204]

- In the United States, amphetamine is a Schedule II prescription drug, classified as a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant.[205]

- Internationally, amphetamine is in Schedule II of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[206][207]

Shortages[edit]

In February 2023, news organizations began reporting on shortages of Adderall in the United States that have lasted for over five months.[208][209] The Food and Drug Administration first reported the shortage in October 2022.[210] In May 2023, 7 months into the shortage, the Food and Drug Administration commissioner Robert Califf stated that "a number of generic drugs are in shortage at any given time because there's not enough profit". He points out that Adderall is a special case because it is a controlled substance and the amount available for prescription is controlled by the Drug Enforcement Administration. He also faults a "tremendous increase in prescribing" due to virtual prescribing and general overprescribing and overdiagnosing, adding that "if only the people that needed these drugs got them, there probably wouldn't be a [stimulant medication] shortage".[211][212]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Salts of racemic amphetamine and dextroamphetamine are mixed in a (1:1) ratio to produce this drug. Because the racemate is composed of equal parts dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine, this drug can also be described as a mixture of the D and (L)-enantiomers of amphetamine in a (3:1) ratio, although none of the components of the mixture are levoamphetamine salts.[1][2]

- ^ The trade name Adderall is used primarily throughout this article because the four-salt composition of the drug makes its nonproprietary name (dextroamphetamine sulfate 25%, dextroamphetamine saccharate 25%, amphetamine sulfate 25%, and amphetamine aspartate 25%) excessively lengthy.[11] Mydayis is a relatively new trade name that is not commonly used to refer generally to the mixture.[10]

- ^ The ADHD-related outcome domains with the greatest proportion of significantly improved outcomes from long-term continuous stimulant therapy include academics (≈55% of academic outcomes improved), driving (100% of driving outcomes improved), non-medical drug use (47% of addiction-related outcomes improved), obesity (≈65% of obesity-related outcomes improved), self-esteem (50% of self-esteem outcomes improved), and social function (67% of social function outcomes improved).[43]

The largest effect sizes for outcome improvements from long-term stimulant therapy occur in the domains involving academics (e.g., grade point average, achievement test scores, length of education, and education level), self-esteem (e.g., self-esteem questionnaire assessments, number of suicide attempts, and suicide rates), and social function (e.g., peer nomination scores, social skills, and quality of peer, family, and romantic relationships).[43]

Long-term combination therapy for ADHD (i.e., treatment with both a stimulant and behavioral therapy) produces even larger effect sizes for outcome improvements and improves a larger proportion of outcomes across each domain compared to long-term stimulant therapy alone.[43] - ^ Cochrane reviews are high quality meta-analytic systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials.[49]

- ^ The statements supported by the USFDA come from prescribing information, which is the copyrighted intellectual property of the manufacturer and approved by the USFDA. USFDA contraindications are not necessarily intended to limit medical practice but limit claims by pharmaceutical companies.[80]

- ^ According to one review, amphetamine can be prescribed to individuals with a history of abuse provided that appropriate medication controls are employed, such as requiring daily pick-ups of the medication from the prescribing physician.[81]

- ^ In individuals who experience sub-normal height and weight gains, a rebound to normal levels is expected to occur if stimulant therapy is briefly interrupted.[87][88][89] The average reduction in final adult height from 3 years of continuous stimulant therapy is 2 cm.[89]

- ^ Transcription factors are proteins that increase or decrease the expression of specific genes.[121]

- ^ In simpler terms, this necessary and sufficient relationship means that ΔFosB overexpression in the nucleus accumbens and addiction-related behavioral and neural adaptations always occur together and never occur alone.

- ^ NMDA receptors are voltage-dependent ligand-gated ion channels that requires simultaneous binding of glutamate and a co-agonist (D-serine or glycine) to open the ion channel.[136]

- ^ The review indicated that magnesium L-aspartate and magnesium chloride produce significant changes in addictive behavior;[112] other forms of magnesium were not mentioned.

- ^ The 95% confidence interval indicates that there is a 95% probability that the true number of deaths lies between 3,425 and 4,145.

- ^ The human dopamine transporter contains a high affinity extracellular zinc binding site which, upon zinc binding, inhibits dopamine reuptake and amplifies amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux in vitro.[151][152][153] The human serotonin transporter and norepinephrine transporter do not contain zinc binding sites.[153]

- ^ 4-Hydroxyamphetamine has been shown to be metabolized into 4-hydroxynorephedrine by dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) in vitro and it is presumed to be metabolized similarly in vivo.[170][173] Evidence from studies that measured the effect of serum DBH concentrations on 4-hydroxyamphetamine metabolism in humans suggests that a different enzyme may mediate the conversion of 4-hydroxyamphetamine to 4-hydroxynorephedrine;[173][175] however, other evidence from animal studies suggests that this reaction is catalyzed by DBH in synaptic vesicles within noradrenergic neurons in the brain.[176][177]

- ^ There is substantial variation in microbiome composition and microbial concentrations by anatomical site.[178][179] Fluid from the human colon – which contains the highest concentration of microbes of any anatomical site – contains approximately one trillion (10^12) bacterial cells/ml.[178]

- ^ For uniformity, molar masses were calculated using the Lenntech Molecular Weight Calculator[192] and were within 0.01 g/mol of published pharmaceutical values.

- ^ Amphetamine base percentage = molecular massbase / molecular masstotal. Amphetamine base percentage for Adderall = sum of component percentages / 4.

- ^ dose = (1 / amphetamine base percentage) × scaling factor = (molecular masstotal / molecular massbase) × scaling factor. The values in this column were scaled to a 30 mg dose of dextroamphetamine sulfate. Due to pharmacological differences between these medications (e.g., differences in the release, absorption, conversion, concentration, differing effects of enantiomers, half-life, etc.), the listed values should not be considered equipotent doses.

- Image legend

- ^ (Text color) Transcription factors

Reference notes[edit]

- ^ [14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

- ^ [25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

- ^ [7][18][29][90][91][92]

- ^ [93][94][95][96]

- ^ [18][97][93][95]

- ^ [14][18][29][98]

- ^ a b [115][116][117][118][138]

- ^ [113][115][114][122][123]

- ^ [114][125][126][127]

- ^ [146][83][144][143][147]

- ^ a b [162][170][171][149][172][165][173][174]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (June 2013). "Amphetamine, past and present--a pharmacological and clinical perspective". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 27 (6): 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532. PMC 3666194. PMID 23539642.

- ^ a b Joyce BM, Glaser PE, Gerhardt GA (April 2007). "Adderall produces increased striatal dopamine release and a prolonged time course compared to amphetamine isomers". Psychopharmacology. 191 (3): 669–677. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0550-9. PMID 17031708. S2CID 20283057.

- ^ Vitiello B (April 2008). "Understanding the risk of using medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with respect to physical growth and cardiovascular function". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 17 (2): 459–74, xi. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.010. PMC 2408826. PMID 18295156.

- ^ Graham J, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Coghill D, Danckaerts M, Dittmann RW, et al. (January 2011). "European guidelines on managing adverse effects of medication for ADHD". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 20 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1007/s00787-010-0140-6. eISSN 1435-165X. PMC 3012210. PMID 21042924.

- ^ Kociancic T, Reed MD, Findling RL (March 2004). "Evaluation of risks associated with short- and long-term psychostimulant therapy for treatment of ADHD in children". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 3 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1517/14740338.3.2.93. eISSN 1744-764X. PMID 15006715. S2CID 31114829.

- ^ Clemow DB, Walker DJ (September 2014). "The potential for misuse and abuse of medications in ADHD: a review". Postgraduate Medicine. 126 (5): 64–81. doi:10.3810/pgm.2014.09.2801. eISSN 1941-9260. PMID 25295651. S2CID 207580823.

- ^ a b c d e Stahl SM (March 2017). "Amphetamine (D,L)". Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology (6th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–51. ISBN 9781108228749. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b Patel VB, Preedy VR, eds. (2022). Handbook of Substance Misuse and Addictions. Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 2006. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-92392-1. ISBN 978-3-030-92391-4.

Amphetamine is usually consumed via inhalation or orally, either in the form of a racemic mixture (levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine) or dextroamphetamine alone (Childress et al. 2019). In general, all amphetamines have high bioavailability when consumed orally, and in the specific case of amphetamine, 90% of the consumed dose is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, with no significant differences in the rate and extent of absorption between the two enantiomers (Carvalho et al. 2012; Childress et al. 2019). The onset of action occurs approximately 30 to 45 minutes after consumption, depending on the ingested dose and on the degree of purity or on the concomitant consumption of certain foods (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction 2021a; Steingard et al. 2019). It is described that those substances that promote acidification of the gastrointestinal tract cause a decrease in amphetamine absorption, while gastrointestinal alkalinization may be related to an increase in the compound's absorption (Markowitz and Patrick 2017).

- ^ a b Sagonowsky E (28 August 2017). "Shire launches new ADHD drug Mydayis as it weighs a neuroscience exit". Fierce Pharma. Questex LLC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "National Drug Code Amphetamine Search Results". National Drug Code Directory. United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ "Pharmacology". Evekeo CII (amphetamine sulfate) HCP. Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Prescribing Information & Medication Guide" (PDF). Zenzedi (dextroamphetamine sulfate, USP). Arbor Pharmaceuticals LLC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ a b Montgomery KA (June 2008). "Sexual desire disorders". Psychiatry. 5 (6): 50–55. PMC 2695750. PMID 19727285.

- ^ a b c d "Adderall- dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine aspartate, dextroamphetamine sulfate, and amphetamine sulfate tablet". DailyMed. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. 8 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, US: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 318, 321. ISBN 9780071481274.

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD. ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors. ...

Beyond these general permissive effects, dopamine (acting via D1 receptors) and norepinephrine (acting at several receptors) can, at optimal levels, enhance working memory and aspects of attention. - ^ a b c d Liddle DG, Connor DJ (June 2013). "Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS". Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 40 (2): 487–505. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009. PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Adderall XR- dextroamphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine sulfate and amphetamine aspartate capsule, extended release". DailyMed. Shire US Inc. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W (January 2009). Shoptaw SJ, Ali R (ed.). "Treatment for amphetamine psychosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (1): CD003026. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003026.pub3. PMC 7004251. PMID 19160215.

A minority of individuals who use amphetamines develop full-blown psychosis requiring care at emergency departments or psychiatric hospitals. In such cases, symptoms of amphetamine psychosis commonly include paranoid and persecutory delusions as well as auditory and visual hallucinations in the presence of extreme agitation. More common (about 18%) is for frequent amphetamine users to report psychotic symptoms that are sub-clinical and that do not require high-intensity intervention ...

About 5–15% of the users who develop an amphetamine psychosis fail to recover completely (Hofmann 1983) ...

Findings from one trial indicate use of antipsychotic medications effectively resolves symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.

psychotic symptoms of individuals with amphetamine psychosis may be due exclusively to heavy use of the drug or heavy use of the drug may exacerbate an underlying vulnerability to schizophrenia. - ^ a b Greydanus D. "Stimulant Misuse: Strategies to Manage a Growing Problem" (PDF). American College Health Association (Review Article). ACHA Professional Development Program. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). "Chapter 16: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071827706.

Such agents also have important therapeutic uses; cocaine, for example, is used as a local anesthetic (Chapter 2), and amphetamines and methylphenidate are used in low doses to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and in higher doses to treat narcolepsy (Chapter 12). Despite their clinical uses, these drugs are strongly reinforcing, and their long-term use at high doses is linked with potential addiction, especially when they are rapidly administered or when high-potency forms are given.

- ^ a b Kollins SH (May 2008). "A qualitative review of issues arising in the use of psycho-stimulant medications in patients with ADHD and co-morbid substance use disorders". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 24 (5): 1345–1357. doi:10.1185/030079908X280707. PMID 18384709. S2CID 71267668.

When oral formulations of psychostimulants are used at recommended doses and frequencies, they are unlikely to yield effects consistent with abuse potential in patients with ADHD.

- ^ Stolerman IP (2010). Stolerman IP (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. Berlin, Germany; London, England: Springer. p. 78. ISBN 9783540686989.

- ^ Howell LL, Kimmel HL (January 2008). "Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant addiction". Biochemical Pharmacology. 75 (1): 196–217. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.003. PMID 17825265.

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–76. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216 (1): 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

VMAT2 is the CNS vesicular transporter for not only the biogenic amines DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, and HIS, but likely also for the trace amines TYR, PEA, and thyronamine (THYR) ... [Trace aminergic] neurons in mammalian CNS would be identifiable as neurons expressing VMAT2 for storage, and the biosynthetic enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC).

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Westfall DP, Westfall TC (2010). "Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists". In Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York, US: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071624428.

- ^ a b c d e Lewin AH, Miller GM, Gilmour B (December 2011). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a stereoselective binding site for compounds in the amphetamine class". Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19 (23): 7044–7048. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.007. PMC 3236098. PMID 22037049.

- ^ a b Anthony E (11 November 2013). Explorations in Child Psychiatry. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 93–94. ISBN 9781468421279. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ a b Arnold LE (2000). "Methyiphenidate vs. Amphetamine: Comparative review". Journal of Attention Disorders. 3 (4): 200–211. doi:10.1177/108705470000300403. S2CID 15901046.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Dextroamphetamine; Dextroamphetamine Saccharate; Amphetamine; Amphetamine Aspartate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (June 2013). "Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 27 (6): 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532. PMC 3666194. PMID 23539642.

The intravenous use of d-amphetamine and other stimulants still pose major safety risks to the individuals indulging in this practice. Some of this intravenous abuse is derived from the diversion of ampoules of d-amphetamine, which are still occasionally prescribed in the UK for the control of severe narcolepsy and other disorders of excessive sedation. ... For these reasons, observations of dependence and abuse of prescription d-amphetamine are rare in clinical practice, and this stimulant can even be prescribed to people with a history of drug abuse provided certain controls, such as daily pick-ups of prescriptions, are put in place (Jasinski and Krishnan, 2009b).

- ^ Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Archives of Toxicology. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347. S2CID 2873101.

- ^ Berman S, O'Neill J, Fears S, Bartzokis G, London ED (October 2008). "Abuse of amphetamines and structural abnormalities in the brain". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1141 (1): 195–220. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.031. PMC 2769923. PMID 18991959.

- ^ a b Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K (February 2013). "Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. PMID 23247506.

- ^ a b Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N, Lomedico A, Faraone SV, Biederman J (September 2013). "Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (9): 902–917. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287. PMC 3801446. PMID 24107764.

- ^ a b Frodl T, Skokauskas N (February 2012). "Meta-analysis of structural MRI studies in children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder indicates treatment effects". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 125 (2): 114–126. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01786.x. PMID 22118249. S2CID 25954331.

Basal ganglia regions like the right globus pallidus, the right putamen, and the nucleus caudatus are structurally affected in children with ADHD. These changes and alterations in limbic regions like ACC and amygdala are more pronounced in non-treated populations and seem to diminish over time from child to adulthood. Treatment seems to have positive effects on brain structure.

- ^ a b c d e f Huang YS, Tsai MH (July 2011). "Long-term outcomes with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: current status of knowledge". CNS Drugs. 25 (7): 539–554. doi:10.2165/11589380-000000000-00000. PMID 21699268. S2CID 3449435.

Several other studies,[97-101] including a meta-analytic review[98] and a retrospective study,[97] suggested that stimulant therapy in childhood is associated with a reduced risk of subsequent substance use, cigarette smoking and alcohol use disorders. ... Recent studies have demonstrated that stimulants, along with the non-stimulants atomoxetine and extended-release guanfacine, are continuously effective for more than 2-year treatment periods with few and tolerable adverse effects. The effectiveness of long-term therapy includes not only the core symptoms of ADHD, but also improved quality of life and academic achievements. The most concerning short-term adverse effects of stimulants, such as elevated blood pressure and heart rate, waned in long-term follow-up studies. ... The current data do not support the potential impact of stimulants on the worsening or development of tics or substance abuse into adulthood. In the longest follow-up study (of more than 10 years), lifetime stimulant treatment for ADHD was effective and protective against the development of adverse psychiatric disorders.

- ^ a b c Millichap JG (2010). "Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD". In Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, US: Springer. pp. 121–123, 125–127. ISBN 9781441913968.

Ongoing research has provided answers to many of the parents' concerns, and has confirmed the effectiveness and safety of the long-term use of medication.

- ^ a b c d e Arnold LE, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Kahle J, Young S (February 2015). "Effect of treatment modality on long-term outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0116407. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407. PMC 4340791. PMID 25714373.

The highest proportion of improved outcomes was reported with combination treatment (83% of outcomes). Among significantly improved outcomes, the largest effect sizes were found for combination treatment. The greatest improvements were associated with academic, self-esteem, or social function outcomes.

Figure 3: Treatment benefit by treatment type and outcome group - ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, US: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ a b Bidwell LC, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH (August 2011). "Cognitive enhancers for the treatment of ADHD". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 99 (2): 262–274. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002. PMC 3353150. PMID 21596055.

- ^ Parker J, Wales G, Chalhoub N, Harpin V (September 2013). "The long-term outcomes of interventions for the management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 6: 87–99. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114. PMC 3785407. PMID 24082796.

Only one paper53 examining outcomes beyond 36 months met the review criteria. ... There is high level evidence suggesting that pharmacological treatment can have a major beneficial effect on the core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity) in approximately 80% of cases compared with placebo controls, in the short term.

- ^ Millichap JG (2010). "Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD". In Millichap JG (ed.). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, US: Springer. pp. 111–113. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ^ "Stimulants for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". WebMD. Healthwise. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Scholten RJ, Clarke M, Hetherington J (August 2005). "The Cochrane Collaboration". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 59 (Suppl 1): S147–S149, discussion S195–S196. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602188. PMID 16052183. S2CID 29410060.

- ^ a b Castells X, Blanco-Silvente L, Cunill R (August 2018). "Amphetamines for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (8): CD007813. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007813.pub3. PMC 6513464. PMID 30091808.

- ^ Punja S, Shamseer L, Hartling L, Urichuk L, Vandermeer B, Nikles J, Vohra S (February 2016). "Amphetamines for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (2): CD009996. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009996.pub2. PMC 10329868. PMID 26844979.

- ^ Osland ST, Steeves TD, Pringsheim T (June 2018). "Pharmacological treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with comorbid tic disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (6): CD007990. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007990.pub3. PMC 6513283. PMID 29944175.

- ^ a b c d e "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Mydayis medication guide" (PDF). Mydayis.com. October 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Generic Adderall Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Generic Adderall XR Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Mydayis® (mixed-salts of a single-entity amphetamine product) – First-time generic" (PDF). OptumRx. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ a b Spencer RC, Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW (June 2015). "The Cognition-Enhancing Effects of Psychostimulants Involve Direct Action in the Prefrontal Cortex". Biological Psychiatry. 77 (11): 940–950. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.013. PMC 4377121. PMID 25499957.

The procognitive actions of psychostimulants are only associated with low doses. Surprisingly, despite nearly 80 years of clinical use, the neurobiology of the procognitive actions of psychostimulants has only recently been systematically investigated. Findings from this research unambiguously demonstrate that the cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve the preferential elevation of catecholamines in the PFC and the subsequent activation of norepinephrine α2 and dopamine D1 receptors. ... This differential modulation of PFC-dependent processes across dose appears to be associated with the differential involvement of noradrenergic α2 versus α1 receptors. Collectively, this evidence indicates that at low, clinically relevant doses, psychostimulants are devoid of the behavioral and neurochemical actions that define this class of drugs and instead act largely as cognitive enhancers (improving PFC-dependent function). ... In particular, in both animals and humans, lower doses maximally improve performance in tests of working memory and response inhibition, whereas maximal suppression of overt behavior and facilitation of attentional processes occurs at higher doses.

- ^ Ilieva IP, Hook CJ, Farah MJ (June 2015). "Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 27 (6): 1069–1089. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776. PMID 25591060. S2CID 15788121.

Specifically, in a set of experiments limited to high-quality designs, we found significant enhancement of several cognitive abilities. ... The results of this meta-analysis ... do confirm the reality of cognitive enhancing effects for normal healthy adults in general, while also indicating that these effects are modest in size.

- ^ Bagot KS, Kaminer Y (April 2014). "Efficacy of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in non-attention deficit hyperactivity disorder youth: a systematic review". Addiction. 109 (4): 547–557. doi:10.1111/add.12460. PMC 4471173. PMID 24749160.

Amphetamine has been shown to improve consolidation of information (0.02 ≥ P ≤ 0.05), leading to improved recall.

- ^ Devous MD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ (April 2001). "Regional cerebral blood flow response to oral amphetamine challenge in healthy volunteers". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 42 (4): 535–542. PMID 11337538.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 10: Neural and Neuroendocrine Control of the Internal Milieu". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, US: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 266. ISBN 9780071481274.

Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with reward.

- ^ a b c Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG (January 2014). "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacological Reviews. 66 (1): 193–221. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMC 3880463. PMID 24344115.

- ^ Twohey M (26 March 2006). "Pills become an addictive study aid". JS Online. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Teter CJ, McCabe SE, LaGrange K, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ (October 2006). "Illicit use of specific prescription stimulants among college students: prevalence, motives, and routes of administration". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (10): 1501–1510. doi:10.1592/phco.26.10.1501. PMC 1794223. PMID 16999660.

- ^ Weyandt LL, Oster DR, Marraccini ME, Gudmundsdottir BG, Munro BA, Zavras BM, Kuhar B (September 2014). "Pharmacological interventions for adolescents and adults with ADHD: stimulant and nonstimulant medications and misuse of prescription stimulants". Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 7: 223–249. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S47013. PMC 4164338. PMID 25228824.

misuse of prescription stimulants has become a serious problem on college campuses across the US and has been recently documented in other countries as well. ... Indeed, large numbers of students claim to have engaged in the nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, which is reflected in lifetime prevalence rates of prescription stimulant misuse ranging from 5% to nearly 34% of students.

- ^ Clemow DB, Walker DJ (September 2014). "The potential for misuse and abuse of medications in ADHD: a review". Postgraduate Medicine. 126 (5): 64–81. doi:10.3810/pgm.2014.09.2801. PMID 25295651. S2CID 207580823.

Overall, the data suggest that ADHD medication misuse and diversion are common health care problems for stimulant medications, with the prevalence believed to be approximately 5% to 10% of high school students and 5% to 35% of college students, depending on the study.

- ^ Bracken NM (January 2012). "National Study of Substance Use Trends Among NCAA College Student-Athletes" (PDF). NCAA Publications. National Collegiate Athletic Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Docherty JR (June 2008). "Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 606–622. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124. PMC 2439527. PMID 18500382.

- ^ a b c d Parr JW (July 2011). "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the athlete: new advances and understanding". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 30 (3): 591–610. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.03.007. PMID 21658550.