All Star (song)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

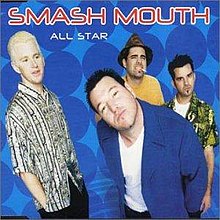

| "All Star" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Smash Mouth | ||||

| from the album Astro Lounge | ||||

| B-side | ||||

| Released | May 4, 1999 | |||

| Recorded | 1999 | |||

| Studio | H.O.S. (Redwood City, California) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 3:21 | |||

| Label | Interscope | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Greg Camp | |||

| Producer(s) | Eric Valentine | |||

| Smash Mouth singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "All Star" on YouTube | ||||

"All Star" is a song by the American rock band Smash Mouth from their second studio album, Astro Lounge (1999). Written by Greg Camp and produced by Eric Valentine, the song was released on May 4, 1999, as the first single from Astro Lounge. The song was one of the last tracks to be written for Astro Lounge, after the band's record label Interscope requested more songs that could be released as singles. In writing it, Camp drew musical influence from contemporary music by artists like Sugar Ray and Third Eye Blind, and sought out to create an "anthem" for outcasts. In contrast to the more ska punk style of Smash Mouth's debut album Fush Yu Mang (1997), the song features a more radio-friendly style.

The song received generally positive reviews from music critics, who praised its musical progression from Fush Yu Mang as well as its catchy tone. It was nominated for the Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals at the 42nd Annual Grammy Awards. Subsequent reviews from critics have regarded "All Star" favorably, with some ranking it as one of the best songs of 1999. The song charted around the world, ranking in the top 10 of the charts in Australia, Canada, and on the Billboard Hot 100, while topping the Billboard Adult Top 40 and Mainstream Top 40 charts.

The song's accompanying music video features characters from the superhero film Mystery Men (1999), which itself prominently featured "All Star". The song became ubiquitous in popular culture following multiple appearances in films, most notably in Mystery Men, Digimon: The Movie and especially DreamWorks Animation's 2001 film Shrek. It received renewed popularity in the 2010s as an internet meme and has ranked as one of the most-streamed rock songs from 2017 to 2021 in the United States.

Background and recording[edit]

"All Star" was the last song recorded for Astro Lounge, Smash Mouth's second album.[1] Along with the rest of the album, the song was produced, mixed, and engineered at H.O.S. Recording in Redwood City, California.[2] Although the band's previous album Fush Yu Mang had sold over two million copies from the strength of its lead single "Walkin' on the Sun", none of the album's other tracks charted well, leading to some labeling the band a one-hit wonder.[3] Eric Valentine, Smash Mouth's producer, said the album had the "dubious distinction" of being very successful but also frequently returned by buyers, as the rest of it sounded very little like the single.[1] For the creation of Astro Lounge, the band decided to shift their musical style away from the ska punk sound that characterized Fush Yu Mang.[1] Greg Camp, Smash Mouth's guitarist, was tasked with writing all of the songs for Astro Lounge due to his pop sensibilities.[1]

After seemingly completing the album, Smash Mouth presented it to their record label Interscope, but the label declined a release because they felt there was no viable first or second single.[1] Robert Hayes, Smash Mouth's manager, offered Camp advice in writing additional songs by pointing him to a copy of Billboard magazine. Hayes showed Camp the top 50 songs on the chart, which featured artists such as Sugar Ray and Third Eye Blind, and told him he wanted "a little piece of each one of these songs".[1] Over the next two days, Camp wrote "All Star" and "Then the Morning Comes", which would become the first two singles from Astro Lounge.[1]

For the writing of "All Star", Camp considered what he had read in the fan mail the band frequently received. Many of the fans that had written to Smash Mouth considered themselves outcasts and identified strongly with the band, and Camp "set out to write an anthem" for them.[1] He also incorporated more melancholy lyrics as well, which contrasted with the upbeat instrumentation.[4] Smash Mouth did not have much time to record the song and brought in Michael Urbano, a session drummer, for recording instead of their regular drummer. According to Valentine, additional drum loops from older songs were used on top of the main drum track. Bassist Paul De Lisle performed the whistling on the song.[1]

Manager Robert Hayes quickly licensed the song out for use in various media, resulting in its appearance in the film Mystery Men just a few months later.[1]

Composition[edit]

"All Star" is set in the key of F♯ major, with a tempo of 104 beats per minute.[5] Writers have described it musically as alternative rock[6] and power pop.[7] Notably, the vocals begin before any instruments, with the first syllable of "somebody" acting as an anacrusis before the bass guitar joins on the second syllable, followed by guitar and organ. The band's label disliked this structure, as did radio stations, but the band fought to keep the song as-is, with Camp stating that, while "[Radio DJs] like to talk over the beginning of your song, [...] they should shut up when our song plays."[8]

During a 2017 interview, Camp stated he was interested in exploring several layers of meaning with the stripped-down song; the social battle cry, the sports anthem, the fanbase affirmation, the poetic lyricism, the sweeping melody, the inclusion, the artistic music videos, and more.[9] Camp described the song as "a daily affirmation that life is, in general, good", something he called a "tradition" for Smash Mouth; according to him, the band frequently read fan mail they received from kids, parents, and teachers thanking them for making "fun and lighthearted" music.[10] In addition to this, Camp has said that the second verse addresses climate change and the hole in the Ozone layer.[11][12]

Critical reception and accolades[edit]

"All Star" was met with generally favorable reviews from music critics, and several critics noted it as an example of Smash Mouth's musical progression from Fush Yu Mang. Todd Norden of the Calgary Herald praised the track as being "a lot better" than the songs on Fush Yu Mang, and the staff of the Associated Press praised it as an example of the "loose and light fare" the band had embraced on Astro Lounge.[13][14] The Morning Call writer John Terlesky favorably mentioned the song as an example of their "new and improved" sound.[15]

The song was also praised for its familiar tone. Stephen Thompson of The A.V. Club lauded it as being "unstoppably infectious", and Rolling Stone writer David Wild felt that the song had potential to be a hit.[16][17] Doug Hamilton of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution called it the "peak" of the album and "the perfect summer anthem".[18] Sandra Sperounes from Edmonton Journal praised "All Star" as an example of Smash Mouth's intelligent songwriting, specifically noting its "veiled references to stupidity".[19] Jay DeFoore of the Austin American-Statesman was more critical, calling the song a "fluffy, made-for-MTV anthem that evaporates into thin air" and "a classic example of hit-by-numbers".[20]

At the 42nd Annual Grammy Awards in 2000, "All Star" was nominated for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals, ultimately losing to Santana's "Maria Maria".[21] Retrospective reviews from the editorial staff of both Billboard and Paste ranked it as one of the best songs of 1999,[22][23] as did Rolling Stone writer Rob Sheffield[24] and Spin writer Taylor Berman.[25] Billboard staff writer Gab Ginsburg noted the song's lasting cultural impact following its appearance in Shrek and the "hundreds" of popular meme videos; Berman felt the song had "a life of its own" and became a "cultural artifact".[22][25] Geoffery Himes of Paste called the song "the best reason to listen to top-40 radio in 1999".[23] In a glowing review, Leor Galil of the Chicago Reader lauded the song for having "transcended genre" to become "permanently stuck in America's hippocampus".[26] Conversely, the staff of Noisey listed it as one of the worst songs of the 1990s, with writer Annalise Domenighini calling the song "the only argument we need for why ska-pop should have never existed in the first place".[27] In 2020, The New York Times listed the song as #1 in their top ten climate change songs.[11]

Release and commercial performance[edit]

"All Star" was released on May 4, 1999,[28][29] as the first single from Astro Lounge.[30][31] Also, it was the first single for the soundtrack album for the superhero film Mystery Men (1999).[10] It entered the Billboard Hot 100 at number 75 on the week of May 22, 1999, and reached its peak position of number 4 on August 14.[32][33] The song peaked at number one on the component Radio Songs chart, as well as on the Adult Top 40 and Mainstream Top 40 charts.[34][35][36] "All Star" peaked at number two and five on the Alternative Songs and Adult Alternative Songs charts, respectively.[37][38] It was later certified triple platinum in the United States by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) for selling 3,000,000 certified units in the United States.[39] The song achieved further success internationally. In Canada, "All Star" peaked at number two on the RPM Top Singles chart and number four and six on the Adult Contemporary and Rock/Alternative charts, respectively.[40][41][42] It charted within the top ten on the Australian Singles Chart and peaked within the top 20 in Finland, Iceland, New Zealand, Scotland, and Spain.[43][44][45][46]

The song ranked at number 17 on the year-end Hot 100 chart and in the top ten of the year-end US Adult Top 40, Alternative Songs, Mainstream Top 40, and Radio Songs charts for 1999.[47][48][49] It additionally appeared on the year-end charts for Australia and Canada, ranking at number 31 and 4, respectively.[50][51] The song has since been certified double platinum in the United Kingdom and platinum in Australia and Italy.[52][53][54]

"All Star" appeared on the Billboard Rock Streaming Songs chart, spending over 100 weeks on the chart and reaching a peak position of number three on the edition of September 21, 2019.[55] The track ranked as one of the most-streamed rock songs of 2017 and 2018, and it ranked at number six on the year-end US Rock Streaming Songs chart in 2019.[56][57][58]

Music video[edit]

Directed by McG, the accompanying music video features cameos by William H. Macy, Ben Stiller, Hank Azaria, Paul Reubens, Kel Mitchell, Janeane Garofalo, Doug Jones, and Dane Cook as their characters from the superhero film Mystery Men, which prominently features the song. Their appearances in the video are primarily based on stock footage from the film; in all other scenes, the characters were portrayed by body doubles and depicted exclusively from behind.[59] The visual opens with the characters from Mystery Men seeking recruits, with the group rejecting several applicants before expressing interest in Smash Mouth singer Steve Harwell.[59] The remainder of the video focuses on Harwell performing several feats (rescuing a dog from a burning building and flipping over a toppled school bus), in addition to scenes from Mystery Men.[59]

In June 2019, the music video was remastered in high definition and received subtitles in commemoration of its 20th anniversary.[60] By that point, it had received over 219 million views on YouTube.[61]

Live performances[edit]

Smash Mouth performed "All Star" at the 1999 Home Run Derby in July at Fenway Park. After the band finished playing, Camp said "Save Fenway Park", referencing plans to demolish the stadium and replace it with a new facility; this elicited boos from the crowd.[62] Smash Mouth performed it on September 9, 1999 in pouring rain, as the opening act of the 1999 MTV Video Music Awards.[63]

A June 14, 2015, performance of the song at Taste of Fort Collins event in Fort Collins, Colorado, went awry after members of the audience started throwing loaves of bread onto the stage. While the rest of the band repeated the opening riff of "All Star", Harwell began a three-minute profanity-filled verbal tirade against the crowd, with him threatening to beat up anyone who threw things onto the stage. Security restrained Harwell after he tried to enter the crowd; the band continued playing while the crowd sang the song in place of him.[64] Smash Mouth performed the song at the Urbana Sweetcorn Festival on August 28, 2016; Harwell passed out in the middle of the set and was taken to a nearby hospital, but the band continued their set and performed the song without him.[65]

Cultural impact[edit]

Film and popular culture[edit]

"All Star" was frequently used in films in the years following its release.[28] The song featured in 1999's Inspector Gadget and Mystery Men, the latter of which was the basis for the song's music video.[29] It appeared the following year in Digimon: The Movie and was even included on the film's soundtrack.[66] It features heavily in the 2001 movie Rat Race, in which the band performs it at a live concert, over the closing credits.[67][68] It regained popularity after being featured in the 2001 DreamWorks animated movie Shrek, where it was played over the opening credits.[1][25] The filmmakers for Shrek had originally used the song as a placeholder for the opening credits and intended to replace it with an original composition by Matt Mahaffey that would mimic the feel of "All Star". However, DreamWorks executive Jeffrey Katzenberg suggested for them to use "All Star" over the sequence instead.[29] Although Smash Mouth was initially apprehensive about being involved with what was considered a family film, DreamWorks was insistent on including the band's music in the film. After being granted an early screening of Shrek, the band members were impressed and ultimately agreed to license "All Star" to appear in the film. They also performed a new rendition of the Monkees' "I'm a Believer" for the ending scene.[1] Vicky Jenson, the co-director of the film, explained that "All Star" perfectly fits the tone and personality of its titular ogre, who is "happy in his solitary existence and has no clue that he has a lot to learn about it".[1] Following the first film, an instrumental of the chorus was briefly played by a marching band at Worcestershire Academy when Shrek, Donkey, and Puss in Boots enter the gymnasium to meet Arthur Pendragon in 2007's Shrek the Third.

"All Star" has been commonly played at sporting events;[1][28][69] it became so popular among sports fans that they were led to play it at Major League Baseball's 1999 Home Run Derby, and have performed it at dozens of sporting events since.[69] The second verse has been used in climate change protests.[11] An unstaged musical theatre adaption of the song, All Star: The Best Broadway Musical, has been written and officially sanctioned by the band. "All Star" is the only song in the musical, being adapted into various genres and styles.[29][70] Siddhant Adlakha of Polygon, who attended a reading of the play, described it as a "jukebox musical, but the jukebox is broken". Regarding the play's concept, Adlakha said it "sounds like the dumbest idea on planet, but I'll be damned if every single member of its cast wasn't committed to the gimmick".[70]

Parodies and memes[edit]

"All Star" has become widely used as an internet meme and is frequently parodied.[28] Remixes and memes have often focused on its connection to Shrek, which has a large online fandom and meme community.[71][72] The song's basic structure lends itself easily towards being used for mashups or remixes;[4] NPR said that the song "seems like it was made to be remixed, mashed-up and squeezed through the meme machine".[73] Both the song's chorus as well as its opening "somebody" line are frequently used as punchlines due to their widespread recognition.[74]

"Mario, You're a Plumber", uploaded to YouTube in 2009 by the channel Richalvarez, has been identified as the earliest parody of "All Star" on the platform.[1][28][71][75] The video, themed around the Nintendo character Mario, has received over 1.6 million views as of 2024.[71] Neil Cicierega released a series of four mashup albums—Mouth Sounds, Mouth Silence, Mouth Moods, and Mouth Dreams—which prominently remixed "All Star" as well as other popular songs from the 1990s.[76] The popularity of 2014's Mouth Sounds, in particular, has been cited as a point where the song received renewed popularity and interest.[75] The track received additional exposure in 2016 from YouTuber Jon Sudano, who reached over a million subscribers by almost exclusively posting videos of himself singing its lyrics over the instrumentals of other songs, eventually going on to rack up over 112 million views as of 2024.[28] Such parodies and memes caused the official music video to experienced a large increase of views on YouTube towards the end of 2016. According to ABC News Radio, it increased from an average of 21,000 views per day to 155,000 a day in December 2016 and reached a peak of 478,000 views per day in 2017.[77] By this point, "All Star" had become so popular on the internet that Austin Powell of The Daily Dot described it as "almost as inescapable now as it once was on commercial radio".[78]

Smash Mouth has embraced the song's status as a meme.[71][78][79] The band was initially hesitant of its newfound popularity, but gradually warmed up to the concept.[71] In an interview with The Daily Dot, Harwell said they consider themselves to have "invented the meme" due to having released 10 remixes of the song through Interscope.[78] According to Harwell, Smash Mouth has "fully accepted" the song as their legacy and consider the "obsession" with it as "a level of love [they are] more than appreciative of".[71] Although the band has received requests to feature on remixes or covers, Smash Mouth has declined to be involved in any because "we feel if other people do it, it adds to the beauty, but if we did it, we feel it would cheapen it".[71] Camp, who is no longer with Smash Mouth, said that he was "flattered" at the continued popularity of "All Star" and has befriended Sudano.[4] Camp was particularly appreciative of "The Sound of Smash Mouth", a "sad" mashup with Simon & Garfunkel's "The Sound of Silence" that emphasizes the melancholic lyrics Camp included in "All Star".[4]

Track listings[edit]

|

|

Credits and personnel[edit]

Credits from the liner notes of Astro Lounge[2]

Smash Mouth

- Steve Harwell – vocals

- Greg Camp – guitars, additional keyboards, backing vocals

- Paul De Lisle – bass, vocals

Production

- Eric Valentine – production, engineering, mixing

- Brian Gardner – mastering

- Trevor Adkinson – engineering

- Michael Urbano – drums[1]

Charts[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

| Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications[edit]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[52] | Platinum | 70,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[100] | Platinum | 90,000‡ |

| Germany (BVMI)[101] | Gold | 250,000‡ |

| Italy (FIMI)[53] | Platinum | 50,000‡ |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[102] | Platinum | 60,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[54] | 2× Platinum | 1,200,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[39] | 3× Platinum | 3,000,000‡ |

| ^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Spanos, Brittany (June 12, 2019). "Somebody Once Told Me: An Oral History of Smash Mouth's 'All Star'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Astro Lounge (CD). Interscope. 1999.

- ^ Guerra, Joey (October 8, 1999). "Smash Mouth leaps over the 'Sun'". Houston Chronicle. p. D-9. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Carnes, Aaron (July 9, 2017). "Remixing Smash Mouth's 'All Star' has become an art form, and its writer is loving it". Salon. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ "Smash Mouth 'All Star' Sheet Music". Musicnotes.com. December 15, 1999. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (April 8, 2016). "Two songs you need to hear: Sean Michaels's playlist of the week". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Mortimer, Frank (May 16, 2013). "Making of Lip Dub: FHS 2013". Foxboro Reporter. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015.

- ^ King, Darryn (May 3, 2019). "The Never-ending Life of Smash Mouth's "All Star"". The Ringer. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ "Songfacts Interview: Smash Mouth Songwriter Greg Camp". Songfacts.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Modern Age". Billboard. June 19, 1999. p. 73. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c Pierre-Louis, Kendra (May 22, 2020). "The Climate 'Hot 10 Songs'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "My World's On Fire: We Asked Smash Mouth If 'All Star' Is About Climate Change". www.vice.com. April 11, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Norden, Todd (June 26, 1999). "Smash Mouth's 'Astro Lounge' is built with pop, surf, and garage-rock styles". Calgary Herald. p. B4. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "On Disc". Courier-Post. The Associated Press. July 22, 1999. p. 7C. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Terlesky, John (July 3, 1999). "Disc reviews". The Morning Call. p. A47. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen (June 8, 1999). "Smash Mouth: Astro Lounge". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Wild, David (July 16, 1999). "Another smash for Smash Mouth". Kenosha News. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ Hamilton, Doug (June 7, 1999). "Mini reviews". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. D5. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Sperounes, Sandra (July 3, 1999). "Release me". Edmonton Journal. p. C3. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ DeFoore, Jay (June 20, 1999). "Smash Mouth's 'Astro Lounge' is built with pop, surf, and garage-rock styles". Austin American-Statesman. p. K16. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "Grammy Awards: Best Pop Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group". Rock on the Net. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b "The 99 Greatest Songs of 1999: Staff List". Billboard. April 8, 2019. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Best Songs of 1999". Paste. August 20, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (June 5, 2019). "Rob Sheffield's 99 Best Songs of 1999". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c Berman, Taylor (July 25, 2019). "The Best Alternative Rock Songs of 1999". Spin. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Galil, Leor (July 18, 2019). "After 25 years, Smash Mouth's gold still glimmers". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Staff; Domenighini, Annalise (October 22, 2015). "The 13 Worst Songs from the 90s". Vice. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Thiessen, Christopher (May 3, 2019). "Smash Mouth's 'All Star' at 20: How the pop-rock anthem was saved by memes". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d King, Darryn (May 3, 2019). "The Never-ending Life of Smash Mouth's 'All Star'". The Ringer. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Kenneally, Tim (August 1999). "Smash Mouth's 'All Star' 1999 Spin Interview". Spin. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Catlin, Roger (June 14, 1999). "How Smash Mouth Found Its Groove". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "The Hot 100". Billboard. May 22, 1999. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Smash Mouth Chart History (Radio Songs)". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth Chart History (Adult Pop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth Chart History (Pop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth Chart History (Alternative Airplay)". Billboard. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth Chart History (Adult Alternative Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "American single certifications – Smash Mouth – All Star". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Singles: Issue 8383." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Adult Contemporary: Issue 8469." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Rock/Alternative Tracks: Issue 8376." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth – All Star". ARIA Top 50 Singles. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth: All Star" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Íslenski Listinn (17.6–24.6. 1999)". Dagblaðið Vísir (in Icelandic). June 18, 1999. p. 10. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "1999 The Year in Music: Hot 100" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 52. December 25, 1999. p. YE-48.

- ^ a b c "1999 The Year in Music" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 52. December 25, 1999. pp. YE-100. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "1999 The Year in Music" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 52. December 25, 1999. pp. YE-89. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "ARIA Charts – End Of Year Charts – Top 100 Singles 1999". ARIA. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "RPM 1999 Top 100 Hit Tracks". RPM. December 13, 1999. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ a b "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 1999 Singles" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ a b "Italian single certifications – Smash Mouth – All Star" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana.

- ^ a b "British single certifications – Smash Mouth – All Star". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ a b "Smash Mouth Chart History (Rock Streaming Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Rock Streaming Songs - Year End (2017)". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Rock Streaming Songs - Year End (2018)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Rock Streaming Songs - Year End (2019)". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c Rampton, Mike (February 29, 2020). "A Deep Dive Into The Video For All Star By Smash Mouth". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on March 15, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ @smashmouth (June 24, 2019). "Our All Star video is now remastered in HD! #AllStar20 @UMG @soundmanagement @Interscope" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Hey now: Smash Mouth celebrates an 'All-Star' milestone on Saturday". KTLO-FM. May 3, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Kessler, Martin (November 23, 2018). "Back In 1999, Smash Mouth Stood Up For Fenway Park". WBUR-FM. Archived from the original on November 26, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Basham, David (September 9, 1999). "Smash Mouth Brave Rain While Blink 182 Enjoy Perfect Weather At VMA Opening Act". MTV. Archived from the original on September 12, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Conaboy, Kelly (June 14, 2015). "Smash Mouth Singer Threatens To 'Beat the Fuck' out of Bread Thrower". Gawker. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ "Smash Mouth Singer Collapses Mid-Show And Leaves In Ambulance; Bandmates Continue Show". WAAF. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Aitchison, Sean (May 6, 2019). "The Weird History of Digimon: The Movie's Banger Soundtrack". Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (May 29, 2014). "We Interviewed the Shit out of the Dude from Smash Mouth". Noisey. VICE Media. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ Semley, John (September 20, 2012). "Smash Mouth, Guy Fieri, and Sammy Hagar Team Up for Awful Cookbook". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Kessler, Martin (July 13, 2018). "The Origin Of Smash Mouth's 'All Star,' An Unintentional Sports Anthem". WBUR-FM. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Adlakha, Siddhant (October 12, 2018). "There's a Smash Mouth musical, and the only song in it is 'All Star'". Polygon. Archived from the original on November 22, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alexander, Julia (November 27, 2017). "Smash Mouth is learning to be cool with 'All Star' memes on YouTube". Polygon. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Sims, David (May 19, 2014). "Why Is the Internet So Obsessed With Shrek?". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Garcia-Navarro, Lulu; Alvarez Boyd, Sophia; Abshire, Emily (July 1, 2018). "Yes, Smash Mouth Has Seen The 'All Star' Memes". NPR. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Hosken, Patrick (May 6, 2019). "'All Star' At 20: How A Smash Mouth Victory Ode Launched A Thousand Memes". MTV. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Saxena, Jaya (December 27, 2017). "The Internet's Endless Obsession with Smash Mouth's "All Star"". GQ. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Romano, Aja (March 7, 2017). "This '90s kid turned his love of a decade into the internet's best mashup albums". Vox. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ "Hey now: Smash Mouth celebrates an "All-Star" milestone on Saturday". ABC News Radio. May 3, 2019. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c Powell, Austin (January 10, 2017). "Smash Mouth finally responds to all those weird 'All Star' memes". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ Plaugic, Lizzie (January 5, 2017). "Smash Mouth: We 'fully embrace the meme'". The Verge. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ All Star (7" single). United States: Interscope. 1999.

- ^ All Star (CD). Australasia, Europe, United States: Interscope. 1999.

- ^ All Star (CD). Interscope. 1999.

- ^ All Star (Cassette). Europe: Interscope. 1999.

- ^ a b All Star (CD). United Kingdom: Interscope. 1999.

- ^ "Smash Mouth – All Star" (in Dutch). Ultratip. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Eurochart Hot 100 Singles" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 16, no. 32. August 7, 1999. p. 6. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "Smash Mouth – All Star" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 31, 1999" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ "Smash Mouth – All Star" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Smash Mouth – All Star". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Smash Mouth – All Star" Canciones Top 50. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Smash Mouth – All Star". Singles Top 100. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ "Listy bestsellerów, wyróżnienia :: Związek Producentów Audio-Video". Polish Airplay Top 100. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ "RPM 1999 Top 100 Adult Contemporary". RPM. December 13, 1999. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "RPM 1999 Top 50 Rock Tracks". RPM. December 13, 1999. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "The Best of '99: Most Played Triple-A Songs". Airplay Monitor. Vol. 7, no. 52. December 24, 1999. p. 38.

- ^ "Most Played Adult Top 40 Songs of 2000". Airplay Monitor. Vol. 8, no. 51. December 22, 2000. p. 48.

- ^ "Rock Streaming Songs - Year End (2020)". Billboard. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ "Danish single certifications – Smash Mouth – All Star". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Smash Mouth; 'All Star')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "Spanish single certifications – Smash Mouth – All Star". El portal de Música. Productores de Música de España. Retrieved April 13, 2024.