Atatürk's reforms

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism |

|---|

Atatürk's Reforms (Turkish: Atatürk İnkılâpları) were a series of political, legal, religious, cultural, social, and economic policy changes, designed to convert the new Republic of Turkey into a secular nation-state, implemented under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in accordance with the Kemalist framework. His political party, the Republican People's Party (CHP), ran Turkey as a one-party state and implemented these reforms, starting in 1923. After Atatürk's death, his successor İsmet İnönü continued the one-party rule and Kemalist style reforms until the CHP lost to the Democrat Party in Turkey's second multi-party election in 1950.[citation needed]

Central to the reforms was the belief that Turkish society had to modernize, which meant implementing widespread reform affecting not only politics, but the economic, social, educational and legal spheres of Turkish society.[1] The reforms involved a number of fundamental institutional changes that brought an end to many traditions, and followed a carefully planned program to unravel the complex system that had developed over previous centuries.[2]

The reforms began with the modernization of the constitution, including enacting the new Constitution of 1924 to replace the Constitution of 1921, and the adaptation of European laws and jurisprudence to the needs of the new republic. This was followed by a thorough secularization and modernization of the administration, with a particular focus on the education system.[citation needed]

The elements of the political system visioned by Atatürk's Reforms developed in stages, but by 1935, when the last part of the Atatürk's Reforms removed the reference to Islam in the Constitution; Turkey became a secular (2.1) and democratic (2.1), republic (1.1) that derives its sovereignty (6.1) from the people. Turkish sovereignty rests with the Turkish Nation, which delegates its will to an elected unicameral parliament (position in 1935), the Turkish Grand National Assembly. The preamble also invokes the principles of nationalism, defined as the "material and spiritual well-being of the Republic" (position in 1935). The basic nature of the Republic is laïcité (2), social equality (2), equality before law (10), and the indivisibility of the Republic and of the Turkish Nation (3.1)." Thus, it sets out to found a unitary nation-state (position in 1935) with separation of powers based on the principles of secular democracy.

Historically, Atatürk's reforms follow the Tanzimât ("reorganization") period of the Ottoman Empire, that began in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876,[3] Abdul Hamid II's authoritarian regime from 1878–1908 that introduced large reforms in education and the bureaucracy, as well as the Ottoman Empire's experience in prolonged political pluralism and rule of law by the Young Turks during the Second Constitutional Era from 1908 to 1913, and various efforts were made to secularize and modernize the empire in the Committee of Union and Progress's one party state from 1913–1918.

Goals[edit]

National unity[edit]

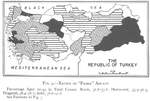

The goal of Atatürk's reforms was to maintain the independence of Turkey from the direct rule of external forces (Western countries).[4] The process was not utopian (in the sense that it is not one leader's idea of how a perfect society should be, but it is a unifying force of a nation), in that Atatürk united the Turkish Muslim majority from 1919 to 1922 in the Turkish War of Independence, and expelled foreign forces occupying what the Turkish National Movement considered to be the Turkish homeland.[4] That fighting spirit became the unifying force which established the identity of a new state, and in 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, ending the Ottoman Empire and internationally recognizing the newly founded Republic of Turkey.[4] From 1923 to 1938, a series of radical political and social reforms were instituted. They transformed Turkey and ushered in a new era of modernization, including civil and political equality for sectarian minorities and women.[4]

Reformation of Islam[edit]

The Ottoman Empire was an Islamic state in which the head of the state, the Sultan, also held the position of Caliph. The social system was organized around the millet structure. The millet structure allowed a great degree of religious, cultural and ethnic continuity across the society but at the same time permitted the religious ideology to be incorporated into the administrative, economic and political system.[5]

There were two sections of the elite group at the helm of the discussions for the future. These were the "Islamist reformists" and the "Westernists". Many basic goals were common to both groups. Some secular intellectuals, and even certain reform-minded Muslim thinkers, accepted the view that social progress in Europe had followed the Protestant reformation, as expressed in François Guizot's Histoire de la civilisation en Europe (1828). The reform-minded Muslim thinkers concluded from the Lutheran experience that the reform of Islam was imperative. Abdullah Cevdet, İsmail Fenni Ertuğrul and Kılıçzâde İsmail Hakkı (İsmail Hakkı Kılıçoğlu), who were westernist thinkers, took their inspiration rather from the subsequent marginalization of religion in European societies.[6] To them, a reformed religion had only a temporary role to play as an instrument for the modernization of society, after which it would be cast aside from public life and limited to personal life.[6]

Westernization[edit]

The Young Turks and other Ottoman intellectuals asked the question of the position of the empire regarding the West (primarily taken to mean Christian Europe).[7] The West represented intellectual and scientific ascendancy, and provided the blueprint for the ideal society of the future.[7]

Political reforms[edit]

Republicanism[edit]

Until the proclamation of the republic, the Ottoman Empire was still in existence, with its heritage of religious and dynastic authority. The Ottoman monarchy was abolished by the Ankara Government, but its traditions and cultural symbols remained active among the people (though less so among the elite).

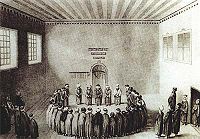

On 1 November 1922, the Ottoman Sultanate was abolished by the Turkish Grand National Assembly and Sultan Mehmed VI departed the country. This allowed the Turkish nationalist government in Ankara to become the sole governing entity in the nation. The most fundamental reforms allowed the Turkish nation to exercise popular sovereignty through representative democracy. The Republic of Turkey ("Türkiye Cumhuriyeti") was proclaimed on 29 October 1923, by the Turkish Grand National Assembly.

The Turkish Constitution of 1921 was the fundamental law of Turkey for a brief period. It was ratified by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in the middle of the Turkish War of Independence. It was a simple document consisting of only 23 short articles. The major driving force behind the preparation of the 1921 Constitution was that its sovereignty derived from the nation and not from the Sultan, the absolute monarch of the Ottoman Empire. The 1921 Constitution also served as the legal basis for the Turkish War of Independence during 1919–1923, since it refuted the principles of the Treaty of Sèvres of 1918 signed by the Ottoman Empire, by which a great majority of the Empire's territory would have to be ceded to the Entente powers that had won the First World War. In October 1923 the constitution was amended to declare Turkey to be a republic.

In April 1924, the constitution was replaced by an entirely new document, the Turkish Constitution of 1924.

Civic independence (popular sovereignty)[edit]

The establishment of popular sovereignty involved confronting centuries-old traditions. The reform process was characterized by a struggle between progressives and conservatives. The changes were both conceptually radical and culturally significant. In the Ottoman Empire, the people of each millet had traditionally enjoyed a degree of autonomy, with their own leadership, collecting their own taxes and living according to their own system of religious/cultural law. The Ottoman Muslims had a strict hierarchy of ulama, with the Sheikh ul-Islam holding the highest rank. A Sheikh ul-Islam was chosen by a royal warrant among the qadis of important cities. The Sheikh ul-Islam issued fatwas, which were written interpretations of the Quran that had authority over the community. The Sheikh ul-Islam represented the law of shariah. This office was in the Evkaf Ministry. Sultan Mehmed VI's cousin Abdulmecid II continued on as Ottoman Caliph.

Besides the political structure; as a part of civic independence, religious education system was replaced by a national education system on 3 March 1924, and The Islamic courts and Islamic canon law gave way to a secular law structure based on the Swiss Civil Code, which is detailed under their headings.

Abolition of Caliphate (1924) and Millet System[edit]

In the secular state or country purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion and claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of religion, and claims to avoid preferential treatment for a citizen from a particular religion/nonreligion over other religions/nonreligion.[8] Reformers followed the European model (French model) of secularization. In the European model of secularizing; states typically involves granting individual religious freedoms, disestablishing state religions, stopping public funds to be used for a religion, freeing the legal system from religious control, freeing up the education system, tolerating citizens who change religion or abstain from religion, and allowing political leadership to come to power regardless of religious beliefs.[9] In establishing a secular state, the Ottoman Caliphate, held by the Ottomans since 1517, was abolished and to mediate the power of religion in the public sphere (including recognized minority religions in the Treaty of Lausanne) left to the Directorate for Religious Affairs. Under the reforms official recognition of the Ottoman millets withdrawn. Shar’iyya wa Awqaf Ministry followed the Office of Caliphate. This office was replaced by the Presidency of Religious Affairs.

The abolishing of the position of Caliphate and Sheikh ul-Islam was followed by a common, secular authority. Many of the religious communities failed to adjust to the new regime. This was exacerbated by emigration or impoverishment, due to deteriorating economic conditions. Families that hitherto had financially supported religious community institutions such as hospitals and schools stop doing so.

Directorate for Religious Affairs[edit]

Atatürk's reforms define laïcité (as of 1935) as permeating both the government and the religious sphere. Minority religions, like the Armenian or Greek Orthodoxy are guaranteed protection by the constitution as individual faiths (personal sphere), but this guarantee does not give any rights to any religious communities (social sphere). (This differentiation applies to Islam and Muslims as well. Atatürk's reforms, as of 1935, assume the social sphere is secular.) The Treaty of Lausanne, the internationally binding agreement of the establishment of the Republic, does not specify any nationality or ethnicity. Treaty of Lausanne simply identifies non-Muslims in general and provides the legal framework which gives certain explicit religious rights to Jews, Greeks, and Armenians without naming them.

The Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) was an official state institution established in 1924 under article 136, which received the powers of the Shaykh al-Islam. As specified by law, the duties of the Diyanet are “to execute the works concerning the beliefs, worship, and ethics of Islam, enlighten the public about their religion, and administer the sacred worshiping places”.[10] The Diyanet exercised state oversight over religious affairs and ensuring that people and communities did not challenge the Republic's "secular identity".[11]

Public administration[edit]

New capital[edit]

The reform movement chose Ankara as its new capital in 1923, as a rejection of the perceived corruption and decadence of cosmopolitan Istanbul and its Ottoman heritage,[12] as well as electing to choose a capital more geographically centered in Turkey. During the disastrous 1912–13 First Balkan War, Bulgarian troops had advanced to Çatalca, mere miles from Istanbul, creating a fear that the Ottoman capital would have to be moved to Anatolia; the reform movement wanted to avoid a similar incident with Turkey.[13]

Advances in the press[edit]

The Anadolu Agency was founded in 1920 during the Turkish War of Independence by Journalist Yunus Nadi Abalıoğlu and writer Halide Edip. The agency was officially launched on 6 April 1920, 17 days before the Turkish Grand National Assembly convened for the first time. It announced the first legislation passed by the Assembly, which established the Republic of Turkey.[14]

However, Anadolu Agency acquired an autonomous status after Atatürk reformed the organizational structure (added some of his closest friends) to turn the Anadolu Agency into a western news agency. This new administrative structure declared the "Anadolu Agency Corporation" on 1 March 1925. Anadolu Agency Corporation acquired an autonomous status with an unexampled organizational chart not existed even in the western countries in those days.[15]

Statistical and census information[edit]

Ottomans had censuses (1831 census, 1881–82 census, 1905–06 census, and 1914 census) performed, and financial information collected under Ottoman Bank for the purpose of payments on Ottoman public debt. One of the Atatürk's major achievement is the establishment of a principal government institution in charge of statistics (economic and financial statistical data) and census data.

Modern statistical services began with the establishment of The Central Statistical Department in 1926. It was established as a partially centralized system. Turkish Statistical Institute is the Turkish government agency commissioned with producing official statistics on Turkey, its population, resources, economy, society, and culture. It was founded in 1926 and has its headquarters in Ankara.[16] In 1930, the title of the Department was changed to The General Directorate of Statistics (GDS), and The National Statistical System was changed to a centralized system. In earlier years, statistical sources were relatively simple and data collection was confined to activities related to some of the relevant functions of the government with population censuses every five years, and with agriculture and industry censuses every ten years.[17] Gradually the activities of the GDS widened in accordance with the increasing demand for new statistical data and statistics. In addition to those censuses and surveys, many continuous publications on economic, social and cultural subjects were published by this institute to provide necessary information.[18]

Social reforms[edit]

Some social institutions had religious overtones, and held considerable influence over public life. Social change also included centuries old religious social structures that has been deeply rooted within the society, some were established within the state organisation of the Ottoman Empire. The Kemalist reforms brought effective social change on women's suffrage.

Religious reform[edit]

In the Ottoman public sphere religious groups exerted their power. The public sphere, can be defined an area in social life where individuals come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion influence political action. It is "a discursive space in which individuals and groups congregate to discuss matters of mutual interest and, where possible, to reach a common judgment."[19] Atatürk's Reforms target the structure of the public space. The construction of a secular nation-state required important changes in state organization, though Atatürk's reforms benefited from the elaborate blueprints for a future society prepared by the Ottoman proponents of positivism during the Second Constitutional Era. [20] [21]

Religious insignia[edit]

The Ottoman Empire had a social system based on religious affiliation. Religious insignia extended to every social function. It was common to wear clothing that identified the person with their own particular religious grouping and accompanied headgear which distinguished rank and profession throughout the Ottoman Empire. The turbans, fezes, bonnets and head-dresses surmounting Ottoman styles showed the sex, rank, and profession (both civil and military) of the wearer. These styles were accompanied with strict regulation beginning with the reign of Süleyman the Magnificent. Sultan Mahmud II followed on the example of Peter the Great in Russia in modernizing the Empire and used the dress code of 1826 which developed the symbols (classifications) of feudalism among the public. These reforms were achieved through introduction of the new customs by decrees, while banning the traditional customs. The view of their social change proposed that if the permanence of secularism was to be assured by removal of persistence of traditional cultural values (the religious insignia), a considerable degree of cultural receptivity by the public to the further social change could be achieved.

Atatürk's Reforms defined a non-civilized person as one who functioned within the boundaries of superstition. The ulema, according to this classification, was not befit for 'civilized' life, as many argued that they were acting according to superstitions developed throughout centuries. On 25 February 1925, parliament passed a law stating that religion was not to be used as a tool in politics. Kemalist ideology waged a war against superstition by banning the practices of the ulema and promoting the 'civilized' way ("westernization"). The ban on the ulema's social existence came in the form of dress code. The strategic goal was to change the large influence of the ulema over politics by removing them from the social arena. However, there was the danger of being perceived as anti-religious. Kemalists defended themselves by stating "Islam viewed all forms of superstition (non-scientific) nonreligious". The ulema's power was established during the Ottoman Empire with the conception that secular institutions were all subordinate to religion; the ulema were emblems of religious piety, and therefore rendering them powerful over state affairs.[22] Kemalists claimed:

The state will be ruled by positivism not superstition.[22]

An example was the practice of medicine. Kemalists wanted to get rid of superstition extending to herbal medicine, potion, and religious therapy for mental illness, all of which were practiced by the ulema. They excoriated those who used herbal medicine, potions, and balms, and instituted penalties against the religious men who claimed they have a say in health and medicine. On 1 September 1925, the first Turkish Medical Congress was assembled, which was only four days after Mustafa Kemal was seen on 27 August at Inebolu wearing a modern hat and one day after the Kastamonu speech on 30 August.

Official measures were gradually introduced to eliminate the wearing of religious clothing and other overt signs of religious affiliation. Beginning in 1923, a series of laws progressively limited the wearing of selected items of traditional clothing. Mustafa Kemal first made the hat compulsory to the civil servants.[23] The guidelines for the proper dressing of students and state employees (public space controlled by state) was passed during his lifetime. After most of the relatively better educated civil servants adopted the hat with their own he gradually moved further. On the 25 November 1925 the parliament passed the Hat Law which introduced the use of Western style hats instead of the fez.[24] Legislation did not explicitly prohibit veils or headscarves and focused instead on banning fezzes and turbans for men. The law had also influence of school text books. Following the issuing of the Hat Law, images in school text books that had shown men with fezzes, were exchanged with images which showed men with hats.[25] Another control on the dress was passed in 1934 with the law relating to the wearing of 'Prohibited Garments'. It banned religion-based clothing, such as the veil and turban, outside of places of worship, and gave the government the power to assign only one person per religion or sect to wear religious clothes outside of places of worship.[26]

Religious texts, prayer, references[edit]

All printed Qurans in Turkey were in Classical Arabic (the sacred language of Islam) at the time.Translated Qurans existed in private settings. A major point of Atatürk's Reform was, according to his understanding; "...teaching religion in Turkish to Turkish people who had been practicing Islam without understanding it for centuries"[28] Turkish translations published in Istanbul created controversy in 1924. Several renderings of the Quran in the Turkish language were read in front of the public.[29] These Turkish Qurans were fiercely opposed by religious conservatives. This incident impelled many leading Muslim modernists to call upon the Turkish Parliament to sponsor a Quran translation of suitable quality.[30] The Parliament approved the project and the Directorate of Religious Affairs enlisted Mehmet Akif Ersoy to compose a Quran translation and an Islamic scholar Elmalılı Hamdi Yazır to author a Turkish language Quranic commentary (tafsir) titled "Hak Dini Kur'an Dili." Ersoy declined the offer and destroyed his work, to avoid the possible public circulation of a transliteration which may remotely be faulty. Only in 1935 did the version read in public find its way to print.

The program also involved implementing a Turkish adhan, as opposed to the conventional Arabic call to prayer. The Arabic adhan was replaced with the following:

Tanrı uludur

Şüphesiz bilirim, bildiririm

Tanrı'dan başka yoktur tapacak.

Şüphesiz bilirim, bildiririm;

Tanrı'nın elçisidir Muhammed.

Haydin namaza, haydin felaha,

Namaz uykudan hayırlıdır.

Following the conclusion of said debates, the Diyanet released an official mandate on 18 July 1932 announcing the decision to all the mosques across Turkey, and the practice was continued for a period of 18 years. Following the victory of the Democrat Party in the country's first multi-party elections in 1950, a new government was sworn in, led by Adnan Menderes, which restored Arabic as the liturgical language.[31]

The reformers dismissed the imam assigned to the Turkish Grand National Assembly, saying that prayer should be performed in a mosque, not in the parliament.[32] They also removed the "references to religion" from the decorum. The only Friday sermon (khutba) ever delivered by a Turkish head of state was given by Atatürk; this took place at a mosque in Balıkesir during the election campaign. The reformers said that "to repeat the sermons [by a politician in the parliament] of a thousand years ago was to preserve backwardness and promote nescience."[32]

Religious organizations[edit]

The abolishment of Caliphate removed the highest religious-political position. This act left Muslim associations who were institutionalized under the convents and the dervish lodges without higher organizing structure.

The reformers assumed that the original sources, now available in Turkish, would render the orthodox religious establishment (the ‘ulamā’) and the Ṣūfī ṭarīqas obsolete, and thus help to privatize religion as well as produce a reformed Islam.[33] In 1925 institutions of religious covenants and dervish lodges were declared illegal.[34]

The reformers imagined that the elimination of the orthodox and Ṣūfī religious establishments, along with traditional religious education, and their replacement with a system in which the original sources were available to all in the vernacular language, would pave the way for a new vision of Islam open to progress and modernity and usher in a society guided by modernity.[35]

Along with the multi-party period, with Democrats both taking part and winning for the first time in the 1950 Turkish general election, religious establishments started becoming more active in the country.

Religious holiday (Work week)[edit]

Turkey adapted the European workweek and weekend as the complementary parts of the week devoted to labor and rest, respectively. In the Ottoman Empire, the workweek was from Sunday to Thursday and the weekend was Friday and Saturday.

A law enacted in 1935 changed the weekend, which now began Friday afternoon (not Thursday afternoon) and ended on Sunday.[36]

Women's rights[edit]

During a meeting in the early days of the new republic, Atatürk proclaimed:

To the women: Win for us the battle of education and you will do yet more for your country than we have been able to do. It is to you that I appeal.

To the men: If henceforward the women do not share in the social life of the nation, we shall never attain to our full development. We shall remain irremediably backward, incapable of treating on equal terms with the civilizations of the West.[37]

In the following years of Atatürk's Reforms women's rights campaigners in Turkey differed from their sisters (and sympathetic brothers) in other countries. Rather than fighting directly for their basic rights and equality, they saw their best chance in the promotion and maintenance of Atatürk's Reforms, with its espousal of secular values and equality for all, including women.[38]

Equal participation[edit]

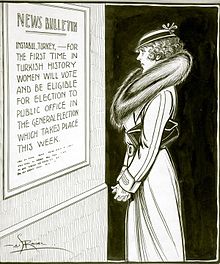

"News bulletin: for the first time in Turkish history women will vote and be eligible to the public office in the general election which takes place this week."

Women were granted the right to vote in Turkey in 1930, but the right to vote was not extended to women in provincial elections in Quebec until 1940.

In Ottoman society, women had no political rights, even after the Second Constitutional Era in 1908. During the early years of the Turkish Republic educated women struggled for political rights. One notable female political activist was Nezihe Muhittin who founded the first women's party in June 1923, which however was not legalized because the Republic was not officially declared.

With intense struggle, Turkish women achieved voting rights in local elections by the act of 1580 on 3 April 1930.[39] Four years later, through legislation enacted on 5 December 1934, they gained full universal suffrage, earlier than most other countries.[39] The reforms in the Turkish civil code, including those affecting women's suffrage, were "breakthroughs not only within the Islamic world but also in the western world".[40]

In 1935, in the general elections Eighteen female MPs joined the parliament, at a time when women in a significant number of other European countries had no voting rights.

Equality of the sexes[edit]

Beginning with the adoption of the Turkish Civil Code in 1926, a modified Swiss Penal Code, women gained extensive civil rights. This continued with women gaining the right to vote and stand for elections at the municipal and federal levels in 1930 and 1934, respectively. Various other legal initiatives were also put into effect in the years following to encourage equality.[41]

The Turkish Civil Code also allowed equal rights to divorce to both men and women, and gave equal child custody rights to both parents.[42]

Polygamy was permitted in the Ottoman Empire under special circumstances, with certain terms and conditions. Atatürk's reforms made polygamy illegal, and became the only nation located in the Middle East that had abolished polygamy, which was officially criminalized with the adoption of the Turkish Civil Code in 1926, a milestone in Atatürk's reforms. Penalties for illegal polygamy was set up to be 2 years imprisonment.[43]

Under Islamic law, a woman's inheritance was half the share of a man, whereas under the new laws man and women inherited equally.[44]

Besides the advancements, men were still officially heads of the household in the law. Women needed the head of the household's permission to travel abroad.[44]

Atatürk's Reforms aimed to break the traditional role of the women in the society. Women were encouraged to attend universities and obtain professional degrees. Women soon became teachers at coed schools, engineers, and studied medicine and law.[45] Between 1920 and 1938, ten percent of all university graduates were women.[44]

In 1930, first female judges were appointed.[44]

Additionally, the female labor participation rate of the Kemalist single-party period was as high as 70%. The participation rate continued to decline after the democratization of Turkey due to the backlash of conservative norms in the Turkish society.[46]

Women's role models[edit]

Atatürk's regime promoted female role models who were, in his words, "the mothers of the nation." This woman of the republic was 'cultured, educated, and modern'; to promote this image, the Miss Turkey pageants were first organized in 1929.[47]

Social structure[edit]

Personal names[edit]

Under the Ottoman Empire many people, especially Muslims, did not use surnames. The Surname Law was adopted on 21 June 1934.[48] The law requires all citizens of Turkey to adopt the use of hereditary, fixed, surnames. Much of the population, particularly in the cities as well as Turkey's Christian and Jewish citizens, already had surnames, and all families had names by which they were known locally.

Measurement (Calendar, time, and the metric system)[edit]

The clocks, calendars and measures used in the Ottoman Empire were different from those used in the European states. This made social, commercial and official relations difficult and caused considerable confusion. In the last period of the Ottoman Empire, some studies were made to eliminate this difference.

First, a law enacted on 26 December 1925 and banned the use of Hijri and Rumi calendars. Turkey began to use Gregorian calendar officially on 1 January 1926. One calendar prevented the complications of multiple calendars in state affairs.[49]

The clock system used by the contemporary world was accepted instead of the Turkish 'sunset clock'. With the time scale taken from the West, one day was divided into 24 hours and daily life was organized accordingly.[49]

With a change made in 1928, international figures were adopted. A law adopted in 1931 changed the old weight and length measurements. Previously used measurement units such as arshin, endaze, okka have been removed. Instead, meters were accepted as length measurements and kilograms as weight measures. With these changes in length and weight measurements, unity was achieved in the country.[49]

Fine art drive[edit]

Among the fine arts, painting, and especially sculpture, were little practiced in the Ottoman Empire, owing to the Islamic tradition of avoiding idolatry.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, in seeking to revise a number of aspects of Turkish culture, used what he saw as the ancient heritage and village life of the country, forcing the removal of perceived Arabic and Persian cultural influences.[50] Metropolitan Museum of Art summarized this period as "While there was a general agreement on the rejection of the last flowering of Ottoman art, no single, all-encompassing style emerged to replace it. The early years of the Republic saw the rise of dozens of new schools of art and the energetic organization of many young artists."[51]

The State Art and Sculpture Museum was dedicated to fine arts and mainly sculpture. It was designed in 1927 by architect Arif Hikmet Koyunoğlu and built between 1927 and 1930 as the Türkocağı Building, upon the direction of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[52] It is located close to the Ethnography Museum and houses a rich collection of Turkish art from the late 19th century to the present day. There are also galleries for guest exhibitions.

Legal reforms[edit]

The Ottoman Empire was a religious empire in which each religious community enjoyed a large degree of autonomy with the Millet structure. Each millet had an internal system of governance based upon its religious law, such as Sharia, Catholic Canon law, or Jewish Halakha. The Ottoman Empire tried to modernize the code with the reforms of 1839 Gülhane Hatt-i Sharif which tried to end confusion in the judicial sphere by extending the legal equality to all citizens.

The leading legal reforms instituted included a secular constitution (laïcité) with the complete separation of government and religious affairs, the replacement of Islamic courts and Islamic canon law with a secular civil code based on the Swiss Civil Code, and a penal code based on that of Italy (1924–37).

Legal system[edit]

On 8 April 1924, sharia courts were abolished with the law Mehakim-i Şer'iyenin İlgasına ve Mehakim Teşkilatına Ait Ahkamı Muaddil Kanun.[53]

Codification[edit]

The non-Muslim millets affected by the Age of Enlightenment in Europe modernized Christian law. In the Ottoman Empire, Islamic law and Christian law became drastically different. In 1920, and today, many forms of Islamic law does not contain provisions regulating the sundry relationships of "political institutions" and "commercial transactions".[54] The rules relating to "criminal cases", shaped under Sharia were too limited in serving their purpose adequately.[54] Beginning with the 19th century, the Ottoman Islamic codes and legal provisions generally were impracticable in dealing with the wider concept of social systems. In 1841, a new criminal code, was drawn up in the Ottoman Empire. However, when the Empire dissolved, there was still no legislation with regard to family and marital relationships.[54] Polygamy was also banned, and was not to be practiced by law-abiding citizens of Turkey after Atatürk's reforms, in contrast to the former rules of the Mecelle.[55] There were thousands of other articles in the Mecelle, which were not used due to their perceived inapplicability.

The adaptation of laws relating to family and marital relationships is an important step attributed to Mustafa Kemal. The reforms also instituted legal equality and full political rights for both sexes in 1934, well before several other European nations. A penal code based on that of Italy was passed between 1924 and 1937.

Educational reforms[edit]

Educational systems (schooling) involve institutionalized teaching and learning in relation to a curriculum, which was established according to a predetermined purpose of education. Ottoman schools were a complex educational system differentiated mainly by curricula. The Ottoman educational system had three main educational groups of institutions. The most common institutions were medreses based on learning Arabic, teaching the Quran using the method of memorization. The second type of institution were the idadî and sultanî, which were the reformist schools of the Tanzimat era. The last group included colleges and minority schools in foreign languages that often used more recent teaching models in educating their pupils.

The unification of education, along with the closure of the old-style universities, and a large-scale program of science transfer from Europe; education became an integrative system, aimed to alleviate poverty and used female education to establish gender equality. Turkish education became a state-supervised system, which was designed to create a skill base for the social and economic progress of the country.[56] Unification came with the Law on Unification of National Education, which introduced three regulations.[57] They placed the religious schools owned by private foundations under the scope of the Ministry of Education. By the same regulations, the Ministry of Education was ordered to open a religious faculty at the Darülfünun (later to become the Istanbul University) and schools to educate imams.[57]

Atatürk's reforms on education made education much more accessible: between 1923 and 1938, the number of students attending primary schools increased by 224% from 342,000 to 765,000, the number of students attending middle schools increased by 12.5 times, from around 6,000 to 74,000 and the number of students attending high schools increased by almost 17 times, from 1,200 to 21,000.[58]

Militarization of education[edit]

Military training was added to the curriculum of secondary education with the support of Mustafa Kemal who stated "just as the army is a school, so is the school an army". He was also in favor of deploying army sergeants as teachers.[59]

Coeducation and the education of girls[edit]

In 1915, during the Ottoman period, a separate section for girl students named the İnas Darülfünunu was opened as a branch of the İstanbul Darülfünunu, the predecessor of the modern Istanbul University.

Atatürk was a strong supporter of coeducation and the education of girls. Coeducation was established as the norm throughout the educational system by 1927.[60] Centuries of sex segregation under Ottoman rule had denied girls equal education, Atatürk thus opposed segregated education as a matter of principle. The matter of coeducation was first raised as a result of a controversy in Tekirdağ in 1924, where, due to the lack of a high school for girls, girls requested enrollment in the high school for boys. Upon this, works on coeducation began and the Minister of Education declared that both sexes would follow the same curriculum. In August 1924, it was decided that coeducation would be introduced to primary education, giving boys the right to enroll in girls' high schools and vice versa. Atatürk declared in his Kastamonu speech in 1925 that coeducation should be the norm. Whilst the educational committee had agreed in 1926 to abolish single-sex education in middle schools that were not boarding schools, segregation persisted in middle and high schools, and statistics in the 1927–28 educational year revealed that only 29% of those enrolled in primary schools were girls. This figure was 18.9% for middle schools and 28% for high schools. Acting on these figures, 70 single-sex middle schools were converted to coeducational schools in 1927–28 and new coeducational middle schools were established. This was despite the opposition of Köprülüzade Fuat Bey, the Undersecretary for Education. Whilst the policy was transition to coeducational high schools based on the success in middle schools from 1928 to 1929 onwards, this policy could only be implemented effectively from 1934 to 1935 onwards.[61]

Higher education[edit]

One of the cornerstone of educational institutions, the University of Istanbul, accepted German and Austrian scientists whom the National Socialist regime in Germany had considered 'racially' or politically undesirable. This political decision (accepting German and Austrian scientists) established the nucleus of science and modern [higher education] institutions in Turkey.[62] The reform aimed to break away the dependency on the transfer of science and technology by foreign experts.[62]

Religious education[edit]

First, all medreses and schools administered by private foundations or the Diyanet were connected to the Ministry of National Education. Second, the money allocated to schools and medreses from the budget of the Diyanet was transferred to the education budget. Third, the Ministry of Education had to open a religious faculty for training higher religious experts within the system of higher education, and separate schools for training imams and hatips.

Improving literacy[edit]

The literacy movement aimed adult education for the goal of forming a skill base in the country. Turkish women were taught not only child care, dress-making and household management, but also skills needed to join the economy outside the home.

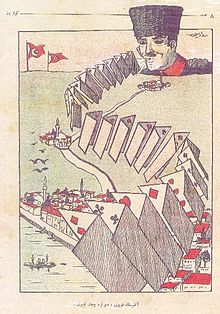

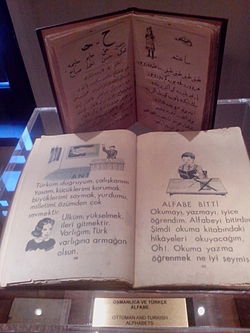

New alphabet[edit]

The adoption of the Latin script and the purging of foreign loan words was part of Atatürk's program of modernization.[63] The two important ends were sought, which were the democratization of writing and language, and the 'secularization' of the Turkish language.

Turkish had been written using a Turkish form of the Perso-Arabic script for a thousand years. It was well suited to write the Ottoman Turkish vocabulary that incorporated a great deal of Arabic and Persian vocabulary and even grammar. However, it was poorly suited for older, Turkic grammar and vocabulary, which was rich in vowels and poorly represented by the Arabic script, an abjad which by definition only transcribed consonants. It was thus inadequate at representing Turkish phonemes. Some could be expressed using four different Arabic signs; others could not be expressed at all. The introduction of the telegraph and printing press in the 19th century exposed further weaknesses in the Arabic script.[64]

Use of the Latin script had been proposed before. In 1862, during Tanzimat, the statesman Münif Pasha advocated a reform of the alphabet. At the start of the 20th century, similar proposals were made by several writers associated with the Young Turks movement, including Hüseyin Cahit, Abdullah Cevdet, and Celâl Nuri.[64] The issue was raised again in 1923 during the first Economic Congress of the newly founded Turkish Republic, sparking a public debate that was to continue for several years. Some suggested that a better alternative might be to modify the Arabic script to introduce extra characters to better represent Turkish vowels.[65]

A language commission responsible for adapting the Latin script to meet the phonetic requirements of the Turkish language was established. The resulting Latin script was designed to reflect the actual sounds of spoken Turkish, rather than simply transcribing the old Ottoman script into a new form.[66] The current 29-letter Turkish alphabet was established. It was a key step in the cultural part of Atatürk's Reforms.[67] The Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) consisting of the following members:[68]

| Linguists | Ragıp Hulûsi Özdem | Ahmet Cevat Emre | İbrahim Grandi Grantay |

| Educators | Mehmet Emin Erişirgil | İhsan Sungu | Fazıl Ahmet Aykaç |

| Writers | Falih Rıfkı Atay | Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın | Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu |

Atatürk himself was personally involved with the commission and proclaimed an "alphabet mobilisation" to publicise the changes. In 1926 the Turkic republics of the Soviet Union adopted the Latin script, giving a major boost to reformers in Turkey.[64] On 1 November 1928, the new Turkish alphabet was introduced by the Language Commission at the initiative of Atatürk, replacing the previously used Perso-Arabic script. The Language Commission proposed a five-year transition period; Atatürk saw this as far too long and reduced it to three months.[69] The change was formalized by the Turkish Republic's law number 1353, the Law on the Adoption and Implementation of the Turkish Alphabet,[70] passed on 1 November 1928. The law went into effect from 1 January 1929, making the use of the new alphabet compulsory in all public communications.[66]

Literacy drive (Millet Mektepleri)[edit]

Before the adoption of the new alphabet a pilot program had been established with 3304 class units around Turkey, awarding a total of 64,302 certificates. This program was declared to be unsuccessful and a new organization was proposed which would be used in the drive to introduce the new alphabet.[71] The name of the new organization which would be used in the literacy drive was "Millet mektepleri".

National Education Minister Mustafa Necati Bey passed the "National Schools Directive" (Directive) 7284 dated 11 November 1928, which stated that every Turkish citizen between the ages of 16–30 (only primary education had been made mandatory at the time) had to join the Millet Mektepleri and this was mandatory. It was also noted that it would be in two stages. Atatürk became the General Chairman of the initial (group I) schools and became the "principal tutor" of 52 schools (teacher training schools) around the country, teaching, course requirements, the money for the provision of classrooms, the use of the media for propaganda purposes, the documents of those schools were successfully established.[71] The active encouragement of people by Atatürk himself, with many trips to the countryside teaching the new alphabet, was successful, which lead to the second stage.

In the first year of the second stage (1928), 20,487 classrooms were opened; 1,075,500 people attended these schools, but only 597,010 received the final certificate. Due to the global economic crisis (Great Depression) there was insufficient funding and the drive lasted only three years and 1 ½ million certificates were presented. The total population of Turkey in this period was less than 10 million, which included the mandatory primary education age pupils who were not covered by this certificate.[71] Eventually, the education revolution was successful, as the literacy rate rose from 9% to 33% in just 10 years.

The literacy reform was supported by strengthening the private publishing sector with a new Law on Copyrights and congresses for discussing the issues of copyright, public education and scientific publishing.

Curriculum secularization and nationalization[edit]

Another important part of Atatürk's reforms encompassed his emphasis on the Turkish language and history, leading to the establishment of the prescriptivist linguistic institution, the Turkish Language Association and Turkish Historical Society for research on Turkish language and history, during the years 1931–2. Adaptation of technical vocabulary was another step of modernization, which was tried thoroughly. Non-technical Turkish was vernacularized and simplified on the ground that the language of Turkish people should be comprehensible by the people. A good example is the Turkish word "Bilgisayar" (bilgi = "information", sayar = "counter"), which was adapted for the word "Computer".

The second president of Turkey, İsmet İnönü explained the reason behind adopting a Latin script: "The alphabet reform cannot be attributed to ease of reading and writing. That was the motive of Enver Pasha. For us, the big impact and the benefit of alphabet reform was that it eased the way to cultural reform. We inevitably lost our connection with Arabic culture."[72]

The alphabet's introduction has been described by the historian Bernard Lewis as "not so much practical as pedagogical, as social and cultural – and Mustafa Kemal, in forcing his people to accept it, was slamming a door on the past as well as opening a door to the future." It was accompanied by a systematic effort to rid the Turkish language of Arabic and Persian loanwords, often replacing them with words from Western languages, especially French. Atatürk told his friend Falih Rıfkı Atay, who was on the government's Language Commission, that by carrying out the reform "we were going to cleanse the Turkish mind from its Arabic roots."[73]

Yaşar Nabi, a leading pro-Kemalist journalist, argued in the 1960s that the alphabet reform had been vital in creating a new Western-oriented identity for Turkey. He noted that younger Turks, who had only been taught the Latin script, were at ease in understanding Western culture but were quite unable to engage with Middle Eastern culture.[74] The new script was adopted very rapidly and soon gained widespread acceptance. Even so, the Turkish Arabic script nonetheless continued to be used by older people in private correspondence, notes and diaries until well into the 1960s.[66]

It was argued by the ruling Kemalist elites who pushed this reform that the abandonment of the Arabic script was not merely a symbolic expression of secularization by breaking the link to Ottoman Islamic texts to which only a minor group of ulema had access; but also Latin script would make reading and writing easier to learn and consequently improve the literacy rate, which succeeded eventually. The change motivated by a specific political goal: to break the link with the Ottoman and Islamic past and to orient the new state of Turkey towards the West and away from the traditional Ottoman lands of the Middle East. He commented on one occasion that the symbolic meaning of the reform was for the Turkish nation to "show with its script and mentality that it is on the side of world civilization."[75]

The idea of absolute monarchy in the textbooks was replaced by the limited ideology known as liberalism. The teachings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Montesquieu based republics were added as content.

Şerif Mardin has noted that "Atatürk imposed the mandatory Latin alphabet in order to promote the national awareness of the Turks against a wider Muslim identity. It is also imperative to add that he hoped to relate Turkish nationalism to the modern civilization of Western Europe, which embraced the Latin alphabet."[76]

The explicitly nationalistic and ideological character of the alphabet reform was illustrated by the booklets issued by the government to teach the population the new script. It included sample phrases aimed at discrediting the Ottoman government and instilling updated "Turkish" values, such as: "Atatürk allied himself with the nation and drove the sultans out of the homeland"; "Taxes are spent for the common properties of the nation. Tax is a debt we need to pay"; "It is the duty of every Turk to defend the homeland against the enemies." The alphabet reform was promoted as redeeming the Turkish people from the neglect of the Ottoman rulers: "Sultans did not think of the public, Ghazi commander [Atatürk] saved the nation from enemies and slavery. And now, he declared a campaign against ignorance. He armed the nation with the new Turkish alphabet."[77]

Economic reforms[edit]

The pursuit of state-controlled economic policies by Atatürk and İsmet İnönü was guided by a national vision: they wanted to knit the country together, eliminate foreign control of the economy, and improve communications. Istanbul, a trading port with international foreign enterprises, was abandoned and resources were channeled to other, less-developed cities, in order to establish a more balanced development throughout the country.[78]

Agriculture[edit]

Agha is the title given to tribal chieftains, either supreme chieftains, or to village heads, who were wealthy landlords and owners of major tracts of real estate in the urban centers.

Throughout the mid-1930s through the mid-1940s, attempts were made at land reforms. Ataturk's land reform program redistributed 300,000 hectares to Turkish peasants and opened rural agricultural institutions to educate peasants to become more productive in economic activities.[79] These reforms further culminated in the reform Law of 1945, 7 years after Ataturk's death. 2.2 million unused land was confiscated by the government in this reform, along with 3.4 government-controlled land, was redistributed to Turkish peasants.[80]

The Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Livestock was established in 1924. The ministry promoted farming through establishing model farms. One of these farms later became a public recreational area to serve the capital, known as the Atatürk Forest Farm.

Industry and nationalization[edit]

The development of industry was promoted by strategies such as import substitution and the founding of state enterprises and state banks.[62] Economic reforms included the establishment of many state-owned factories throughout the country for the agriculture, machine making and textile industries. Many of these grew into successful enterprises and were privatized during the latter part of 20th century.

Turkish tobacco was an important industrial crop, while its cultivation and manufacture were French monopolies under capitulations of the Ottoman Empire. The tobacco and cigarette trade was controlled by two French companies, the Regie Company and Narquileh Tobacco.[81] The Ottoman Empire gave the tobacco monopoly to the Ottoman Bank as a limited company under the Council of the Public Debt. Regie, as part of the Council of the Public Debt, had control over production, storing, and distribution (including export) with an unchallenged price control. Turkish farmers were dependent on Regie for their livelihood.[82] In 1925, this company was taken over by the state and named Tekel.

The development of a national rail network was another important step for industrialization. The State Railways of the Republic of Turkey (Turkish State Railways) was formed on 31 May 1927, and its network was operated by foreign companies. The TCDD later took over the Chemin de Fer d'Anatolie-Baghdad (Anatolian Railway (CFOA)). On 1 June 1927, it had control over the tracks of the former Anatolian Railway (CFOA) and the Transcaucasus Railway line within Turkish borders. This institution developed an extensive railway network in a very short time. In 1927, the road construction goals were incorporated into development plans. The road network consisted of 13,885 km (8,628 mi) of ruined surface roads, 4,450 km (2,770 mi) of stabilized roads, and 94 bridges. In 1935, a new entity was established under the government called "Sose ve Kopruler Reisligi" which would drive development of new roads after World War II. However, in 1937, the 22,000 km (14,000 mi) of roads in Turkey augmented the railways.

Establishing the banking system[edit]

In 1924, the first Turkish bank Türkiye İş Bankası was established. The bank's creation was a response to the growing need for national establishment and the birth of a banking system which was capable of backing up economic activities, managing funds accumulated as a result of policies providing savings incentives and, where necessary, extending resources which could trigger industrial impetus.

In 1931, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey was realized. The bank's primary purpose was to have control over the exchange rate, and Ottoman Bank's role during its initial years as a central bank was phased out. Later specialized banks such as the Sümerbank (1932) and the Etibank (1935) were founded.

International debt/capitulations[edit]

The Ottoman Public Debt Administration (OPDA) was a European-controlled organization that was established in 1881 to collect the payments which the Ottoman Empire owed to European companies in the Ottoman public debt. The OPDA became a vast, essentially independent bureaucracy within the Ottoman bureaucracy, run by the creditors. It employed 5,000 officials who collected taxes that were then turned over to the European creditors.[83] Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire (ahdnames) were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were entered into by each contracting party towards the other, not mere concessions, yet this gradually changed in the 19th century.

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were removed by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), specifically by Article 28. During the Paris Conference of 1925, reformers paid 62% of the Ottoman Empire's pre-1912 debt, and 77% of the Ottoman Empire's post-1912 debt. With the Paris Treaty of 1933, Turkey decreased this amount to its favor and agreed to pay 84.6 million liras out of the remaining total of 161.3 million liras of Ottoman debt. The last payment of the Ottoman debt was made by Turkey on 25 May 1954.

Social policy reforms and economic progress[edit]

Atatürk was also credited for his transformational change in Turkish agriculture and ecological development. The Kemalist government planned four million trees, modernized the Turkish agricultural mechanism, implemented flood controls, opened schools in rural areas with rural institutions such as agricultural banks, and implemented land reform that removed heavy taxes on peasants of the Ottoman era. He was described as the "Father of Turkish Agriculture."[84][85] The Turkish economy developed in an exceptional rate with heavy industrial production increased by 150% and GDP capita rose from 800 USD to around 2000 USD by late 1930s, on par with Japan.[86]

Ataturk’s regime also passed the 1936 Labor Law, which gave substantial wage increases and improved the working conditions of workers in Turkish enterprises.[87]

Analysis[edit]

Arguments over effectiveness[edit]

Some people thought that the pace of change under Atatürk was too rapid as, in his quest to modernize Turkey, he effectively abolished centuries-old traditions. Nevertheless, the bulk of the population willingly accepted the reforms, even though some were seen as reflecting the views of the urban elites at the expense of the generally illiterate inhabitants of the rural countryside, where religious sentiments and customary norms tended to be stronger.[88]

Probably the most controversial area of reform was that of religion. The policy of state secularism ("active neutrality") met with opposition at the time and it continues to generate a considerable degree of social and political tension. However, any political movement that attempts to harness religious sentiment at the expense of Turkish secularism is likely to face the opposition of the armed forces, which has always regarded itself as the principal and most faithful guardian of secularism. Some assert that a historical example is the case of Prime Minister Adnan Menderes, who was overthrown by the military in 1960.[89] He and two of his Ministers were hanged by the Military Tribunal. However, their charges were not for being anti-secular. Although Menderes did relax some restrictions on religion he also banned the Nation Party which was avowedly Islamist. Further, the charges at the Military Tribunal did not involve antisecular activities and it can be concluded that Menderes was overall in favour of the secular system.

Arguments over reform or revolution[edit]

The Turkish name for Atatürk's Reforms literally means "Atatürk's Revolutions", as, strictly speaking, the changes were too profound to be described as mere 'reforms'. It also reflects the belief that those changes, implemented as they were during the one-party period, were more in keeping with the attitudes of the country's progressive elite than with a general populace accustomed to centuries of Ottoman stability – an attempt to convince a people so-conditioned of the merits of such far-reaching changes would test the political courage of any government subject to multi-party conditions.

Military and the republic[edit]

Not only were all the social institutions of Turkish society reorganized, but the social and political values of the state were replaced as well.[90] This new, secular state ideology was to become known as Kemalism, and it is the basis of the democratic Turkish Republic. Since the establishment of the republic the Turkish military has perceived itself as the guardian of Kemalism, and it has intervened in Turkish politics to that end on several occasions, including the overthrow of civilian governments by coup d'état. While this may seem contrary to democratic ideals, it was argued by military authorities and secularists as necessary in the light of Turkish history, ongoing efforts to maintain secular government, and the fact that the reforms were implemented at a time when the military occupied 16.9% of the professional job positions (the corresponding figure today is only 3%).[90]

Milestones[edit]

1920s[edit]

- Political: 1 November 1922: Abolition of the office of the Ottoman Sultanate

- Political: 29 October 1923: Proclamation of the Republic – Republic of Turkey

- Political: 3 March 1924: Abolition of the office of Caliphate held by the Ottoman Caliphate

- Economic: 24 July 1923: Abolition of the capitulations with the Treaty of Lausanne

- Educational: 3 March 1924: The centralization of education

- Legal: 8 April 1924: Abolition of sharia courts

- Economic: 1924: The Weekend Act (Workweek)

- Social: 25 November 1925: Change of headgear and dress

- Social: 30 November 1925: Closure of religious convents and dervish lodges

- Economic: 1925: Establishment of model farms (e.g.: Orman Çiftliği, present-day Atatürk Orman Çiftliği)

- Economic: 1925: The International Time and Calendar System (Gregorian calendar, time zone)

- Legal: 1 March 1926: Introduction of the new penal law modeled after the Italian penal code

- Legal: 4 October 1926: Introduction of the new civil code modeled after the Swiss civil code

- Legal: 1926: The Obligation Law

- Legal: 1926: The Commercial Law

- Economic: 31 May 1927: Establishment of the Turkish State Railways

- Educational 1 January 1928: Establishment of Turkish Education Association

- Educational: 1 November 1928: Adoption of the new Turkish alphabet

1930s[edit]

- Educational: 1931: Establishment of Turkish Historical Society for research on history

- Educational: 12 July 1932: Establishment of Turkish Language Association for regulating the Turkish language

- Economic: 1933: The System of Measures (International System of Units)

- Economic: 1 December 1933: First Five Year Development Plan (planned economy)

- Educational: 31 May 1933: Regulation of the university education

- Social: 21 June 1934: Surname Law

- Social: 26 November 1934: Abolition of titles and by-names

- Political: 5 December 1934: Full political rights for women to vote and be elected.

- Social: 14 October 1935: Closure of the Masonic lodges[91][92][93]

- Political: 5 February 1937: The inclusion of the principle of laïcité (secularism) in the constitution.

- Economic: 1937: Second Five Year Development Plan (planned economy)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ S. N. Eisenstadt, "The Kemalist Regime and Modernization: Some Comparative and Analytical Remarks," in J. Landau, ed., Atatürk and the Modernization of Turkey, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1984, 3–16.

- ^ Jacob M. Landau "Atatürk and the Modernization of Turkey" page 57.

- ^ Cleveland, William L & Martin Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East: 4th Edition, Westview Press: 2009, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Daud, Ismail; Nooraihan, Ali; Fadzli, Adam (January 2015). "Modernization of Turkey under Kamal Ataturk". Asian Social Science. 11 (4): 202–205.

- ^ Öztürk, Fatih. "The Ottoman Millet System". pp. 71–86. - Cited: p. 72

- ^ a b Hanioglu, Sükrü (2011). Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 53.

- ^ a b Hanioglu, Sükrü (2011). Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 54.

- ^ Madeley, John T. S.; Enyedi, Zsolt (2003). Church and State in Contemporary Europe: The Chimera of Neutrality. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-5394-5.[page needed]

- ^ Jean Baubérot The secular principle Archived 2008-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Basic Principles, Aims And Objectives Archived 2011-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, Presidency of Religious Affairs

- ^ Lepeska, David (17 May 2015). "Turkey Casts the Diyanet". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Mango, Atatürk, 391–392

- ^ Şimşir, Bilal. "Ankara'nın Başkent Oluşu" (in Turkish). atam.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "History". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Anadolu Agency celebrates its 99th anniversary". Anadolu Agency.

- ^ "TURKISH STATISTICAL INSTITUTE AND THE HISTORY OF STATISTICS" (PDF). unstats.un.org (United Nations). p. 2.

- ^ "TURKISH STATISTICAL INSTITUTE AND THE HISTORY OF STATISTICS" (PDF). unstats.un.org (United Nations). p. 3.

- ^ "TURKISH STATISTICAL INSTITUTE AND THE HISTORY OF STATISTICS" (PDF). unstats.un.org (United Nations). p. 4.

- ^ Hauser, Gerard (June 1998), "Vernacular Dialogue and the Rhetoricality of Public Opinion", Communication Monographs, 65 (2): 83–107 Page. 86, doi:10.1080/03637759809376439, ISSN 0363-7751.

- ^ Hanioglu, Sükrü (2011). Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 132.

- ^ Mango, Atatürk, 394

- ^ a b Inalcik, Halil. 1973. "Learning, the Medrese, and the Ulemas." In the Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600. New York: Praeger, pp. 171.

- ^ İğdemir, Atatürk, 165–170

- ^ Genç, Kaya (11 November 2013). "Turkey's Glorious Hat Revolution". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Yılmaz, Hale (30 July 2013). Becoming Turkish. Syracuse University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8156-3317-4.

- ^ Yılmaz, Hale (30 July 2013). Becoming Turkish. Syracuse University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8156-3317-4.

- ^ "Burcu Özcan, Basına Göre Şapka ve Kılık Kıyafet İnkılabı, Marmara Üniversitesi, Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü, Yüksek Lisans Tezi, İstanbul 2008". Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Michael Radu, (2003), "Dangerous Neighborhood: Contemporary Issues in Turkey's Foreign Relations", page 125, ISBN 978-0-7658-0166-1

- ^ Cleveland, A History of the Modern Middle East, 181

- ^ Wilson, M. Brett. "The First Translations of the Quran in Modern Turkey (1924–1938)". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 41 (3): 419–435. doi:10.1017/s0020743809091132. S2CID 73683493.

- ^ Atalay, Hidayet Aydar Mehmet (18 April 2012). "THE ISSUES OF CHANTING THE ADHAN IN LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ARABIC AND RELATED SOCIAL REACTIONS AGAINST IT IN TURKEY". Journal of Istanbul University Faculty of Theology (13): 45–63.

- ^ a b Hanioglu, Sükrü (2011). Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. pp. 141–142.

- ^ Hanioglu, Sükrü (2011). Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 149.

- ^ William Dalrymple: What goes round... The Guardian, Saturday 5 November 2005 Dalrymple, William (5 November 2005). "What goes round..." The Guardian. London.

- ^ Hanioglu, Sükrü (2011). Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 150.

- ^ "TAKVİM, SAAT VE ÖLÇÜLERDE DEĞİŞİKLİK". MEB (Education deportment of Turkey).

- ^ Kinross, Patrick Balfour Baron (1964). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 343. ISBN 978-90-70091-28-6.

- ^ Nüket Kardam "Turkey's Engagement With Global Women's Human Rights" page 88.

- ^ a b Türkiye'nin 75 yılı, Tempo Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 1998, p.48,59,250

- ^ Necla Arat in Marvine Howe's Turkey today, page 18.

- ^ Mangold-Will, Sabine (October 2012). "Şükrü M. Hanioğlu, Atatürk. An Intellectual Biography. Princeton/Oxford, Princeton University Press 2011 Hanioğlu Şükrü M. Atatürk. An Intellectual Biography. 2011 Princeton University Press Princeton/Oxford £ 19,95". Historische Zeitschrift. 295 (2): 548. doi:10.1524/hzhz.2012.0535. ISSN 0018-2613.

- ^ Kandiyoti, Deniz A. Emancipated but unliberated? : reflections on the Turkish case. OCLC 936700178.

- ^ "Turkish Penal Code, Art. 230". Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d Eylem Atakav "Women and Turkish Cinema: Gender Politics, Cultural Identity and Representation, page 22

- ^ White, Jenny B. (2003). "State Feminism, Modernization, and the Turkish Republican Woman". NWSA Journal. 15 (3): 145–159. doi:10.2979/NWS.2003.15.3.145 (inactive 15 April 2024). JSTOR 4317014. Project MUSE 53246.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - ^ Göksel, İdil (November 2013). "Female labor force participation in Turkey: The role of conservatism". Women's Studies International Forum. 41: 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2013.04.006.

- ^ Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü (24 May 2018). "Turkey and the West". 1. Princeton University Press. doi:10.23943/princeton/9780691175829.003.0009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ 1934 in history, Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

- ^ a b c "TAKVİM, SAAT VE ÖLÇÜLERDE DEĞİŞİKLİK". MEB (Education deportment of Turkey).

- ^ Sardar, Marika. “Art and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century Turkey.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- ^ "Art and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century Turkey". metmuseum (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

- ^ "Turkish Architecture Museum Database: Arif Hikmet Koyunoğlu". Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ M. Sükrü Hanioglu (9 May 2011). Ataturk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-4008-3817-2. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Timur, Hıfzı. 1956. "The Place of Islamic Law in Turkish Law Reform", Annales de la Faculté de Droit d'Istanbul. Istanbul: Fakülteler Matbaası.

- ^ Dr. Ayfer Altay "Difficulties Encountered in the Translation of Legal Texts: The Case of Turkey", Translation Journal volume 6, No. 4.

- ^ Ozelli, M. T. (January 1974). "The Evolution of the Formal Educational System and its Relation to Economic Growth Policies in the First Turkish Republic". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 5 (1): 77–92. doi:10.1017/S0020743800032803.

- ^ a b "Education since republic". Ministry of National Education (Turkey). Archived from the original on 20 July 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ Kapluhan, Erol (2011), Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nde Atatürk Dönemi Eğitim Politikaları (1923–1938) ve Coğrafya Eğitimi (PhD thesis) (in Turkish), Marmara University, pp. 203–5

- ^ Üngör, Ugur Ümit (1 March 2012). The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950. OUP Oxford. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-19-164076-6.

- ^ Landau, Atatürk and the Modernization of Turkey, 191.

- ^ Kapluhan, Erol (2011), Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nde Atatürk Dönemi Eğitim Politikaları (1923–1938) ve Coğrafya Eğitimi (PhD thesis) (in Turkish), Marmara University, pp. 232–7

- ^ a b c Regine ERICHSEN, «Scientific Research and Science Policy in Turkey», in Cemoti, n° 25 – Les Ouïgours au vingtième siècle, [En ligne], mis en ligne le 5 décembre 2003.

- ^ Nafi Yalın. The Turkish language reform: a unique case of language planning in the world, Bilim dergisi 2002 Vol. 3 page 9.

- ^ a b c Zürcher, Erik Jan. Turkey: a modern history, p. 188. I.B.Tauris, 2004. ISBN 978-1-85043-399-6

- ^ Gürçağlar, Şehnaz Tahir. The politics and poetics of translation in Turkey, 1923–1960, pp. 53–54. Rodopi, 2008. ISBN 978-90-420-2329-1

- ^ a b c Zürcher, p. 189

- ^ Yazım Kılavuzu, Dil Derneği, 2002 (the writing guide of the Turkish language)

- ^ "Harf Devrimi". dildernegi.org.tr. Dil Derneği. Retrieved 22 March 2023.[dead link]

- ^ Gürçağlar, p. 55

- ^ "Tūrk Harflerinin Kabul ve Tatbiki Hakkında Kanun" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 24 June 2009.

- ^ a b c İbrahim Bozkurt, Birgül Bozkurt, Yeni Alfabenin Kabülü Sonrası Mersin’de Açılan Millet Mektepleri ve Çalışmaları, Çağdaş Türkiye Araştırmaları Dergisi, Cilt: VIII, Sayı: 18–19, Yıl: 2009, Bahar-Güz Archived 8 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ İsmet İnönü (August 2006). "2". Hatıralar (in Turkish). Bilgi Yayinevi. p. 223. ISBN 975-22-0177-6.

- ^ Toprak, p. 145, fn. 20

- ^ Toprak, p. 145, fn. 21

- ^ Karpat, Kemal H. "A Language in Search of a Nation: Turkish in the Nation-State", in Studies on Turkish politics and society: selected articles and essays, p. 457. BRILL, 2004. ISBN 978-90-04-13322-8

- ^ Cited by Güven, İsmail in "Education and Islam in Turkey". Education in Turkey, p. 177. Eds. Nohl, Arnd-Michael; Akkoyunlu-Wigley, Arzu; Wigley, Simon. Waxmann Verlag, 2008. ISBN 978-3-8309-2069-4

- ^ Güven, pp. 180–81

- ^ Mango, Atatürk, 470

- ^ Singer, Morris (July 1983). "Atatürk's Economic Legacy". Middle Eastern Studies. 19 (3): 301–311. doi:10.1080/00263208308700552. JSTOR 4282948.

- ^ DEMİREL, Zerrin; GÜLSEVER, Fatma Zehra. "Land Reform and Practices in Turkey". OICRF. Yildiz Technical University. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, 232–233.

- ^ Aysu, Abdullah (29 January 2003). "Tütün, İçki ve Tekel" (in Turkish). BİA Haber Merkezi. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ Donald Quataert, "The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922" (published in 2000.)

- ^ Budak, Derya Nil. "Atatürk, The National Agricultural Leader, Father of Modern Turkish Agriculture and The National Development: A Review From the Perspective of Agricultural Communications and Leadership" (PDF).

- ^ "Factories established by Atatürk, the founder of Turkey, in first 15 years of Republic". 23 November 2020.

- ^ Colpan, Asli M.; Jones, Geoffrey (June 2011). Vehbi Koç and the Making of Turkey's Largest Business Group (Report). Harvard Business School. Case 811-081.

- ^ Singer, Morris (July 1983). "Atatürk's Economic Legacy". Middle Eastern Studies. 19 (3): 301–311. doi:10.1080/00263208308700552. JSTOR 4282948.

- ^ Kinross, Patrick Balfour Baron (1964). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 503. ISBN 978-90-70091-28-6.

- ^ Kinross, Patrick Balfour Baron (1964). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 504. ISBN 978-90-70091-28-6.

- ^ a b Ali Arslan "The evaluation of parliamentary democracy in turkey and Turkish political elites" HAOL, núm. 6 (invierno, 2005), 131–141.

- ^ "TURKISH BAN ON FREEMASONS. All Lodges To Be Abolished". Malaya Tribune, 14 October 1935, p. 5. The Government has decided to abolish all Masonic lodges in Turkey on the ground that Masonic principles are incompatible with nationalistic policy.

- ^ "Tageseinträge für 14. Oktober 1935". chroniknet. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Atatürk Döneminde Masonluk ve Masonlarla İlişkilere Dair Bazı Arşiv Belgeleri by Kemal Özcan

Further reading[edit]

- Bein, Amit. Ottoman Ulema, Turkish Republic: Agents of Change and Guardians of Tradition (2011)

- Ergin, Murat. "Cultural encounters in the social sciences and humanities: western émigré scholars in Turkey," History of the Human Sciences, Feb 2009, Vol. 22 Issue 1, pp 105–130

- Hansen, Craig C. "Are We Doing Theory Ethnocentrically? A Comparison of Modernization Theory and Kemalism," Journal of Developing Societies (0169796X), 1989, Vol. 5 Issue 2, pp 175–187

- Hanioglu, M. Sukru. Ataturk: An intellectual biography (2011)

- Kazancigil, Ali and Ergun Özbudun. Ataturk: Founder of a Modern State (1982) 243pp

- Ward, Robert, and Dankwart Rustow, eds. Political Modernization in Japan and Turkey (1964).

- Yavuz, M. Hakan. Islamic Political Identity in Turkey (2003)

- Zurcher, Erik. Turkey: A Modern History (2004)

- "The Myth of 'New Turkey': Kemalism and Erdoganism as Two Sides of the Same Coin". Dr. Ceren Şengül. News About Turkey.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Atatürk's reforms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Atatürk's reforms at Wikimedia Commons