Blood on the Sun

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Blood on the Sun | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Frank Lloyd |

| Written by | Garrett Fort Lester Cole |

| Produced by | William Cagney |

| Starring | James Cagney Sylvia Sidney Porter Hall |

| Cinematography | Theodor Sparkuhl |

| Edited by | Walter Hannemann |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa |

Production company | William Cagney Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $750,000[1] |

| Box office | $3.4 million[2][3] |

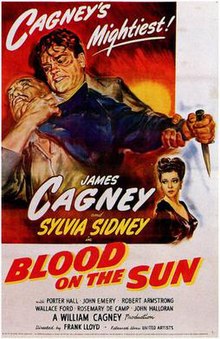

Blood on the Sun is a 1945 American spy thriller film directed by Frank Lloyd and starring James Cagney, Sylvia Sidney and Porter Hall. The film is based on a fictional history behind the Tanaka Memorial document.

The film won the Academy Award for Best Art Direction for a Black & White (Wiard Ihnen, A. Roland Fields) film in 1945.[4]

Plot[edit]

In 1929, the existence of the “Tanaka Memorial,” a Japanese plan devised by Baron Giichi Tanaka to conquer the world, is published in the Tokyo Chronicle. The Japanese secret police visit the newspaper's headquarters, demanding that editor Nick Condon disclose the source, which he refuses to do.

Ollie Miller, a Chronicle reporter who obtained the original plan, makes plans to take it out of Japan. After Miller flaunts the money he was paid for his services at a local press bar, a secret police informer there arranges to have Miller killed. When Condon goes to Miller's cabin on the ship, to see him off, he finds Ollie's wife Edith murdered and their cabin ransacked. Condon narrowly misses another woman exiting the cabin, but glimpses a ruby ring on her hand. Later that night, Miller is shot outside Condon’s house. Before he dies, Miller gives Condon his copy of the Tanaka Memorial plan. As the secret police, led by Captain Oshima, arrive, Condon hides the document in his bedroom, behind a portrait of Emperor Hirohito. Revering the portrait, Oshima does not search it, but ransacks the rest of Condon's house and subdues him when he resists.

Condon wakes up the next morning in a prison cell. The Japanese police have fabricated a story about him having a drunken party the previous night and fixed his house to hide the damage, and the document is missing. Condon’s search for it is interrupted by a courier inviting him to Baron Tanaka’s home. At Tanaka’s home, the Baron offers Condon a substantial sum of money if he returns the document. Condon realizes Tanaka does not have the document, someone else took it.

Suspecting that the other party consists of Japanese anti-war liberals interested in sneaking the document out of the country, Condon publicly announces his intention to return to the United States. That evening, he meets Iris Hilliard, a half-Chinese woman. Seeing a ring on her finger, he suspects she was the woman he saw fleeing Edith’s cabin, but the two are attracted to one another. Unbeknownst to him, Iris is a spy for Baron Tanaka, tasked with retrieving the plan.

Disgruntled at being passed over as Condon’s replacement as editor, Cassell, an unscrupulous reporter, inadvertently reveals to Condon that Tanaka ordered him to introduce Iris to him. Armed with this knowledge, Condon confronts Iris, who confesses that, while she does work for Tanaka, in her heart she is loyal to Japan’s liberal fraction. Having no fear of the Emperor’s portrait, she took the Tanaka Memorial from his house. Condon takes the document and leaves. Eavesdropping on their conversation, the secret police imprison Iris in her hotel room, but she escapes. Disgraced by his failure, Tanaka commits seppuku.

Before Condon leaves for the United States, Iris contacts him, asking to meet on a fishing dock. Evading the secret police tailing him, Condon meets Iris, who is accompanied by Prince Tatsugi, a liberal within the Japanese government who hates the right-wing militarists. Aware that the Japanese government will claim the document is a forgery, Tatsugi places his signature on it, legitimizing it. The police arrive and kill Tatsugi. Condon gives the document to Iris, who flees in a fishing boat. Condon stays behind to delay the policemen.

After defeating Captain Oshima at judo and evading the secret police, Condon arrives outside the United States embassy. He is shot and incapacitated, but when the Japanese search him, they are unable to find the document. An American diplomat rushes from the embassy to help Condon. The head of the secret police asks Condon to forgive his enemy, but he refuses a proffered handshake and replies, “Sure, forgive your enemies – but first, get even!”

Cast[edit]

- James Cagney as Nick Condon

- Sylvia Sidney as Iris Hilliard

- Porter Hall as Arthur Bickett

- John Emery as Premier Giichi Tanaka

- Robert Armstrong as Col. Hideki Tojo

- Wallace Ford as Ollie Miller

- Rosemary DeCamp as Edith Miller

- John Halloran as Capt. Oshima

- Leonard Strong as Hijikata

- James Bell as Charley Sprague

- Marvin Miller as Yamada

- Rhys Williams as Joseph Cassell

- Frank Puglia as Prince Tatsugi

Uncredited Cast

- Hugh Beaumont as Johnny Clarke

- Emmett Vogan as Johnson

Adaptations[edit]

Blood on the Sun was adapted as a radio play on the December 3, 1945 episode of Lux Radio Theater with James Cagney and on the October 16, 1946 episode of Academy Award Theater starring John Garfield.[5]

Production[edit]

Los Angeles Policeman Jack Sergel was featured in several magazine stories listing him as a top judo expert. William Cagney contacted him about teaching his brother James judo for the film. Sergel adopted the stage name John Halloran to appear as Cagney's opponent in the film. He later appeared in several of James Cagney's films, including teaching judo to Edmund O'Brien in White Heat,[6]

Release[edit]

The film's world premiere was held on May 2, 1945, at the United Artists Theatre in San Francisco, with Cagney and Sidney in attendance. The premiere was part of a series of screenings coinciding with the World Security Conference, during which the United Nations was founded. Several hundred conference delegates attended the premiere.

The film opened the following day at the same theater and grossed a record $13,213 in its first four days, $3000 more than any previous film at the theater. By the end of its first week, it had grossed $20,605, when the house average was $12,000.[7]

The film was shown in special screenings to US soldiers, sailors and Marines serving on Okinawa, Iwo Jima and in Manila on May 25, 1945, before its general release throughout the United States.[8]

The film opened in Cincinnati on June 14, 1945, and then in New York on June 28, 1945, at the Capitol Theatre, with a stage show including Mark Warnow and his orchestra, singer Rose Marie, actor Jack Durant and organist Ethel Smith.[9]

Copyright status and home media[edit]

In 1973, the film entered the public domain in the United States because the owners did not renew its copyright registration in the 28th year after publication.[10] As a result of this, it has been released in many substandard budget editions with inferior video and audio quality, and missing four minutes of footage.[11]

Its original uncut length was 94 minutes,[12] though an original running time of 98 minutes has been much perpetuated with no supporting evidence whatsoever.

For many years there were very few quality home video editions. In 1993, Republic Pictures had the film computer-colorized using a high-quality print.[13] This was subsequently released on DVD in the US (2003, Artisan Entertainment) and UK (2000, Eureka Entertainment).[11] The film was again released on US DVD (2001, Image Entertainment) with a transfer licensed from the Hal Roach Library. The rear sleeve states: "DIGITALLY MASTERED FROM THE ORIGINAL NITRATE CAMERA NEGATIVE. Blood on the Sun has historically suffered by being presented in very poor 16mm and 35mm dupe versions, most of which contained a very serious indigenous jitter. This stunning digital transfer was made from the brilliant original nitrate camera negative, which remains in mint condition after almost six decades."[11] The DVD has a running time of 94 minutes.

The film was released on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber on February 13, 2024, using a new 2020 HD Master created by Paramount Pictures from a 4K scan of original surviving 35mm nitrate elements.[14]

In other media[edit]

In the television series Cagney & Lacey, the character Christine Cagney has the poster of Blood on the Sun in her apartment ,[15] with the strapline "Cagney's Mightiest" adding to her characterization.[16]

References[edit]

- ^ "Indies $70,000,000 Pix Output". Variety: 3. 3 November 1944. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ The United Artists Story p 109

- ^ Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists: The Company Built by the Stars. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-23004-3. p217

- ^ "NY Times: Blood on the Sun". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-10-18. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ ""Blood on the Sun" Next "Academy" Show". Harrisburg Telegraph. Harrisburg Telegraph. October 12, 1946. p. 17. Retrieved October 1, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ pp. 334-335 Weaver, Tom, Schecter, David, Kiss, Robert J. & Kronenberg, Steve Universal Terrors, 1951-1955: Eight Classic Horror and Science Fiction Films McFarland, 15 Sep. 2017

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/motionpicturedai57unse_0/motionpicturedai57unse_0_djvu.txt

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/motionpicturedai57unse_0/motionpicturedai57unse_0_djvu.txt

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/motionpicturedai57unse_0/motionpicturedai57unse_0_djvu.txt

- ^ Pierce, David (March 29, 2001). Legal Limbo: How American Copyright Law Makes Orphan Films (mp3 in "file3"). Orphans of the Storm II: Documenting the 20th Century. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ^ a b c "Blood on the Sun (1945) DVD comparison". DVDCompare.

- ^ "Blood on the Sun (1945)". BBFC.

- ^ PA0000742134 / 1993-10-07

- ^ https://kinolorber.com/product/blood-on-the-sun

- ^ "Choices". Cagney & Lacey. Series 3. Episode 7. 31:46 minutes in.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (1984-07-02). "'Cagney & Lacey, Police series on CBS". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

External links[edit]

- Blood on the Sun at IMDb

- Blood on the Sun at AllMovie

- Blood on the Sun on YouTube

- Blood on the Sun at the TCM Movie Database

- Blood on the Sun at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Blood on the Sun is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive