Bobby Benson and the B-Bar-B Riders

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

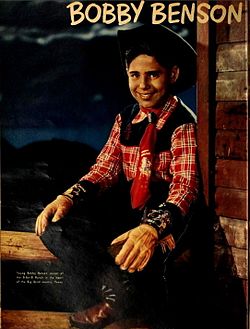

Bobby Benson as portrayed in Radio TV Mirror magazine's August 1950 issue. The actor was Ivan Cury. | |

| Other names | Bobby Benson's Adventures The H-Bar-O Rangers B-Bar-B Ranch B-Bar-B Songs Bobby Benson and Sunny Jim |

|---|---|

| Genre | Juvenile Western adventure |

| Running time | 15 minutes (1932-1936) 30 minutes (1949-1955) |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Language(s) | English |

| Home station | WGR |

| Syndicates | CBS Mutual |

| Starring | Richard Wanamaker (1932-1933) Billy Halop (1933 - 1936) Ivan Cury (1949-1950) Clyde Campbell (1951-1955) |

| Announcer | Dan Seymour André Baruch Art Millet Bob Emerick Bucky Cosgrove Carl Warren |

| Created by | Herbert C. Rice |

| Written by | Peter Dixon John Battle Jim Shean |

| Directed by | Bob Novak |

| Original release | October 17, 1932 – June 17, 1955 |

| Opening theme | "Westward Ho" |

| Sponsored by | Hecker H-O Company Kraft Foods |

Bobby Benson and the B-Bar-B Riders is an old-time radio juvenile Western adventure program in the United States, one of the first juvenile radio programs.[1] It was broadcast on CBS October 17, 1932 - December 11, 1936, and on Mutual June 21, 1949 - June 17, 1955.[2]

Background[edit]

Bobby Benson was created by Herbert C. Rice, who had already originated "dozens of local drama series" as a director at a radio station in Buffalo, New York.[1] In 1932, representatives of the Hecker H-O Company of Buffalo sought to develop a children's radio program for the company's cereal products. Rice associated the "H-O" name with a cattle brand and soon developed a concept about an orphan named Bobby Benson and his guardian, Sunny Jim (an icon used to represent H-O cereals).[1] The program was called The H-Bar-O Rangers while it was sponsored by Hecker.[2]

Format[edit]

After his parents' deaths, 12-year-old Bobby Benson inherited the B-Bar-B Ranch in Big Bend, Texas. That development paved the way for adventures as, week after week, outlaws and other bad people tried to cause problems for the ranch and its people. Young Bobby was helped by Tex Mason, his foreman.[3] Jim Cox, in his book Radio Crime Fighters: More Than 300 Programs from the Golden Age, described the program as

capturing the imagination of little tykes and older adolescents as Bobby and his ranch hands stumbled upon exploits well beyond an ordinary youngster's reach. Most of Benson's escapades involved the pursuit and capture of contingents of bandits and desperadoes of diverse sorts. Rustlers, smugglers, bank and stagecoach robbers dotted the scripts like cactus spread across the Western plains.[4]

Relief from the show's drama and suspense came in the form of songs sung around a campfire and humorous tall tales told by handyman Windy Wales.[4] In a column in the May 15, 1938, issue of the trade publication Broadcasting, writer Pete Dixon noted that inclusion of comedy segments boosted the show's popularity: "Bobby Benson & the H-Bar-O Rangers was just another juvenile western until ... comedy characters were introduced in the script. Comedy situations were alternated with melodrama. Within a year the Bobby Benson show jumped from tenth place among juvenile favorites to first place. Comedy accounted for the climb."[5]

In 1949, a reviewer for the trade publication Billboard wrote, "Kids still go for good old-fashioned Western adventure, and this show is loaded with fast action and fancy gun play, yet wholesome enough to please the most exacting parent."[6]

The program was set in the modern West, with devices like automobiles and airplanes in addition to horses.[1]

From 1932 to 1936, episodes were 15 minutes long and varied in frequency from two to five times a week. From 1949 to 1955, episodes were 30 minutes long, airing three to five times per week.[1] In 1949, Rice (who had become production manager for Mutual) explained the reason for lengthening episodes: "Here we have taken a show that was a highly successful 15 minute strip back in 1932. It ran for five years commercially and sold a lot of cereal. We have modernized it into a half hour complete feature story. We recognize that "cliffhangers" for boys and girls are outdated. We know our juvenile audience has been conditioned to expect a well-constructed thirty minute drama."[7]

Personnel[edit]

Characters in Bobby Benson and the B-Bar-B Riders and the actors who portrayed them are shown in the table below.

| Character | Actor |

|---|---|

| Bobby Benson | Richard Wanamaker (1932-1933) Billy Halop (1933 - 1936) Ivan Cury (1949-1950) Clyde Campbell (1951-1955) |

| Tex (Buck) Mason | Herbert C. Rice (1932-1936) Charles Irving (1949-1951) Bob Haig (1952-1955) Neil O'Malley[1] |

| Sunny Jim | Detmar Popper[1] |

| Polly Armistead | Florence Halop |

| Windy Wales | Don Knotts |

| Harka | Craig McDonnell |

| Irish | Craig McDonnell |

| Aunt Lilly | Larraine Pankow |

| Wong Lee (cook)[1] | Herbert C. Rice |

| Tia Maria | Athena Lord[1] |

| Diogenes Dodwaddle | Tex Ritter |

| Black Bart | Eddie Wragge |

Source: Radio Crime Fighters: More Than 300 Programs from the Golden Age[4] except as noted.

Others heard on the program's 1932–1936 run included Joe Wilton, John Shea, Jean Sothern, Walter Tetley, Bert Parks, David Dixon and Fred Dampier. Others in the 1949-1955 version included Bill Zuckert, Earl George, Ross Martin, Gil Mack and Jim Boles.[1]

The cast listed above staffed the main production on the East Coast, first in Buffalo, New York, (originating at WGR radio)[8] and later in New York City. Meanwhile, in 1933, a separate production began in Los Angeles for audiences on the West Coast; its cast included George Breakston as Bobby, Jean Darling as Polly, Lawrence Honeyman as Black Bart and Muriel Reynolds as Aunt Lilly.[1]

Announcers from 1932 through 1936 included Dan Seymour, André Baruch and Art Millet.[2] Announcers for the 1949–1955 run included Bob Emerick, Bucky Cosgrove and Carl Warren.[1]: 26

Audience response[edit]

Jack French wrote in the book Radio Rides the Range: A Reference Guide to Western Drama on the Air, 1929-1967 "[The program's] initial success was nothing short of phenomenal. Within a few months, the Hecker Company had to assign 12 women full-time to answer the fan mail and process the box tops of H-O Oats that arrived daily in exchange for premiums advertised on the show: Bobby Benson code books, cereal bowls, card games, and drinking tumblers."[1] Because many families had little extra money in the 1930s, the company offered options for redeeming premiums. Cox wrote, "A ranger's holster, gun or cartridge belt could be ordered for a box top and 15 cents or for five box tops ... ranger's chaps, one box top and $1.45 or 25 box tops; ranger's hat, one box top and 85 cents or 20 box tops ..."[4]

The program's popularity was also indicated by the number of subscriptions to H-Bar-O News, a weekly publication mailed to children who sent in one box top from the sponsor's cereals. The February 1, 1934, issue of Broadcasting reported that circulation of the newspaper had exceeded 250,000. Each 16-page four-color issue included "comic strips, articles on western life which are tied up with the radio show, a western mystery serial and many other features," including some items submitted by readers."[9]

Daniel de Visé wrote in his book, Andy and Don: The Making of a Friendship and a Classic American TV Show, that when the program returned in 1949, it had similar popularity: "The revival worked: Bobby Benson again became a household name, at least among prepubescent boys. B-Bar-B riders formed clubs across the nation."[10] Representatives of the show attended county fairs and rodeos all along the East Coast.[10]

As another example of the show's popularity, Radio Digest reported in its January 16, 1950, issue: "B-Bar-B Ranch recently pulled 250,000 letters in ten days as the result of the formation of a ranch club ..."[11] Also, for a "Bobby Benson Day" promotion at the R.H. Macy & Co. store in New York City in 1950, an estimated 20,000 people ("mostly excited kids") showed up, which a Macy's executive said was "the largest turnout ever at a Macy promotion."[12]

Songs of the B-Bar-B[edit]

A spinoff of the program began in 1951 when a chewing gum manufacturer wanted to sponsor a program but couldn't afford much time on the air. The result was Songs of the B-Bar-B, a five-minute show with a tall tale sandwiched between two songs.[1]

Other media[edit]

Comic books[edit]

In 1950, Magazine Enterprises began publishing Bobby Benson's B-Bar-B Riders, a comic book adaptation of the radio program. As time went on, the Lemonade Kid and Ghost Rider were incorporated into the storylines.[13]

Comic strips[edit]

After Bobby Benson and the B-Bar-B Riders was canceled in 1936, the Hecker H-O Company continued to promote the concept of "The Cowboy Kid" via advertisements in the form of comic strips that were printed in newspapers in the northeastern United States.[1]

Television[edit]

On April 18, 1950, WOR-TV in New York City began a 30-minute television version of the program. Two mainstays from the radio broadcast, Herb Rice and Pete Dixon, worked on the TV show as producer and writer, respectively.[14] A second TV version in the 1950s "featured a greatly reduced cast."[13]

Related activities[edit]

Merchandising[edit]

In 1950, Mutual licensed the merchandising rights for Bobby Benson items, the first time the network had done so for any program. Jerry Sanford & Company had plans to sell 15 items related to the show "including cowboy hats and shirts, record albums, sweat shirts, gun holsters, various clothing accessories, and a comic book."[15] By May 1950, more than 300 department stores in the United States carried Benson-related items. Sales from March to May totaled more than $300,000 — part of which went to Mutual as royalties.[16]

Amusement park[edit]

In 1951, Palisades Park in New Jersey entered into an agreement to renovate its 16-ride "kiddieland" area "to resemble a ranch and corral setting."[17] An article in Billboard said, "Benson's name and B-Bar-B Ranch will be plugged extensively thru special billing and other media."[17] Kraft Caramels, which sponsored the program, prepared a merchandising program for selling candy in the park and prepared promotional material to be displayed at candy dealers' stores. The contract also called for personal appearances by the actor portraying Benson on the air.[17]

Personal appearances[edit]

In the spring of 1950, a tour by the actor portraying Benson included appearances in Paterson, New Jersey; Richmond, Virginia; and Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania; with an appearance at the Ringling Bros. Barnum and Bailey Circus at Madison Square Garden as the highlight of the tour.[18] A live production based on the show toured in the early 1950s. A story in the October 6, 1951, issue of Billboard reported on the Shrine Show scheduled for December 8–9, 1951, in Miami, Florida. "First attraction signed," it said, "was Bobby Benson, kid star of the Mutual Broadcasting Company's (MBS) B-Bar-B stanza. The show will run two and one-half hours."[19]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o French, Jack; Siegel, David S. (2013). Radio Rides the Range: A Reference Guide to Western Drama on the Air, 1929-1967. McFarland. pp. 22–30. ISBN 9781476612546. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (1999). Radio Programs, 1924-1984: A Catalog of More Than 1800 Shows. McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-4513-4. Pp. 48-49.

- ^ a b c d Cox, Jim (2002). Radio Crime Fighters: More Than 300 Programs from the Golden Age. McFarland. pp. 54–56. ISBN 9781476612270. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ Dixon, Pete (May 15, 1938). "A Paucity of Fun for Kids" (PDF). Broadcasting. p. 42. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Bundy, June (July 2, 1949). "B-Bar-B Ranch" (PDF). Billboard. p. 13. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Alicoate, Jack (Publisher) (1949). Radio Daily Shows of Tomorrow (PDF) (10th ed.). p. 25. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ Thornburg, W.H. (February 15, 1933). "Boosting Cereal Sales Exclusively by Radio" (PDF). Broadcasting. p. 7. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Chrildren's Feature News Has 250,000 Readers" (PDF). Broadcasting. February 1, 1934. p. 38. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ a b Visé, Daniel de (2016). Andy and Don: The Making of a Friendship and a Classic American TV Show. Simon and Schuster. p. 48. ISBN 9781476747743. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Benson Show Strong Puller" (PDF). Radio Daily. January 16, 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ ""Bobby Benson" Day Draws 20,000 Kids" (PDF). Radio Daily. March 8, 1950. p. 4. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ a b Green, Paul (2016). Encyclopedia of Weird Westerns: Supernatural and Science Fiction Elements in Novels, Pulps, Comics, Films, Television and Games, 2d ed. McFarland. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9781476624020. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Bobby Benson Bows As WOR-TV Video Feature" (PDF). Radio Daily. April 12, 1950. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "MBS Sells Merchandising Rights to Kid Show" (PDF). Billboard. March 4, 1950. p. 10. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Not sponsored -- but big business". Sponsor. May 22, 1950. pp. 36–35, 52–55. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ a b c "Palisades' Kid Spot Gets Cowboy Motif" (PDF). Billboard. March 3, 1951. p. 43. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Bobby Benson Days" (PDF). Radio Daily. April 5, 1950. p. 6. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "Van Deusen Wins Miami Shrine Pact" (PDF). Billboard. October 6, 1951. p. 50. Retrieved 23 December 2016.