Khanbaliq

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Khanbaliq (Dadu of Yuan) | |

|---|---|

| Native name 汗八里 Wade-Giles: Han-pa-li | |

| (元)大都 (Yüan) Ta-tu | |

| |

| Type | Former capital city |

| Location | Beijing, China |

| Coordinates | 39°56′0″N 116°24′0″E / 39.93333°N 116.40000°E |

| Founded | 1264 |

| Founder | Kublai Khan |

| Khanbaliq | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 汗八里 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Хаан балгас, Ханбалиг | ||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠻᠠᠨᠪᠠᠯᠢᠺ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dadu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | (元)大都 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Grand Capital (of Yuan) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠠᠶᠢᠳᠤ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Beiping | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 北平 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | [Seat of the] Northern Pacified [Area] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Khanbaliq or Dadu of Yuan (Chinese: 元大都Mongolian: ᠻᠠᠨᠪᠠᠯᠢᠺ) was the winter capital[1] of the Yuan dynasty of China in what is now Beijing, the capital of China today. It was located at the center of modern Beijing. The Secretariat directly administered the Central Region (腹裏) of the Yuan dynasty (comprising present-day Beijing, Hebei, Shandong, Shanxi, and parts of Henan and Inner Mongolia) and dictated policies for the other provinces. As emperors of the Yuan dynasty, Kublai Khan and his successors also claimed supremacy over the entire Mongol Empire following the death of Möngke (Kublai's brother and predecessor) in 1259. Over time the unified empire gradually fragmented into a number of khanates.

Khanbaliq is the direct predecessor to modern Beijing. Several stations of Line 10 and Line 13 are named after the gates of Dadu.

Name[edit]

The name Khanbaliq comes from the Mongolian and Old Uyghur[2] words khan and balik[3] ("town", "permanent settlement"): "City of the Khan". It was actually in use among the Turks and Mongols before the fall of Zhongdu, in reference to the Jin emperors of Manchuria. It is traditionally written as Cambaluc in English, after its spelling in Rustichello's retelling of Marco Polo's travels. The Travels also uses the spellings Cambuluc and Kanbalu.

The name Dadu is the pinyin transcription of the Chinese name 大都, meaning "Grand Capital". The Mongols also called the city Daidu,[4] which was a transliteration directly from the Chinese.[5] In modern Chinese, it is referred to as Yuan Dadu to distinguish it from other cities which have similar names.

History[edit]

Zhongdu, the "Central Capital" of the Jurchen Jin dynasty, was located at a nearby site now part of Xicheng District. It was destroyed by Genghis Khan in 1215 when the Jin court began contemplating a move south to a more defensible capital such as Kaifeng. The Imperial Mint (诸路交钞提举司) established in 1260 and responsible for the printing of jiaochao, the Yuan fiat paper money, was probably located at nearby Yanjing even before the establishment of the new capital.[6]

In 1264, Kublai Khan visited the Daning Palace on Jade Island in Taiye Lake and was so enchanted with the site that he directed his capital to be constructed around the garden. The chief architect and planner of the capital was Liu Bingzhong,[7][8] who also served as supervisor of its construction.[9] His student Guo Shoujing and the Muslim Ikhtiyar al-Din were also involved.[10]

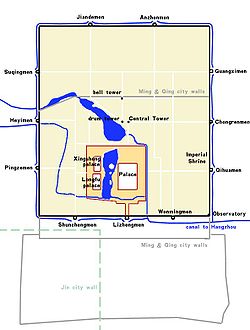

The construction of the walls of the city began in the same year, while the main imperial palace (大内) was built from 1274 onwards. The design of Khanbaliq followed several rules laid down in the Confucian classic The Rites of Zhou, including "9 vertical and horizontal axes", "palaces in front, markets in back", "ancestral worship to the left, divine worship to the right".[clarification needed] It was broad in scale, strict in planning and execution, and complete in equipment.[11]

A year after the 1271 establishment of the Yuan dynasty, Kublai Khan proclaimed the city his capital under the name Dadu[12] as it is interpreted capital city in Hanzi and named Khanbaliq as referred in the state diplomatic letters in Mongolian. The construction was not fully completed until 1293. His previous seat at Shangdu (Xanadu) became the summer capital.

As part of the Great Khans' policy of religious tolerance, Khanbaliq had various houses of worship. Almost every major religious tradition and sect in China and the wider world had a presence in the city.[13] Orders of rabbi, Taoist sects, Mongol shamans, and various kinds of Hindu religious groups were some of the most well-known religious minorities in the city.[14] Buddhists, Muslims, Church of the East Christians, Catholics, and Confucianists were more common.[15]

Confucians and Taoists were extremely well-regarded by most Mongol nobles, and "some of the Mongols' most esteemed advisors were Taoists and Confucians."[15]

It even was the seat of a Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Khanbaliq from 1307 until its 1357 suppression.[citation needed] It was restored in 1609 as (then) Diocese of Peking.

The Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty sent an army to Dadu in 1368. The last Yuan emperor fled north to Shangdu while the Ming razed the palaces of their capital to the ground.[16] The former capital was renamed Beiping[17] (北平 "Pacified North") and Shuntian Prefecture was established in the area around the city.

The Hongwu Emperor was succeeded by his young grandson the Jianwen Emperor. His attempts to rein in the fiefs of his powerful uncles provoked the Jingnan Rebellion and ultimately his usurpation by his uncle, the Prince of Yan. Yan's powerbase lay in Shuntian and he quickly resolved to move his capital north from Yingtian (Nanjing) to the ruins at Beiping. He shortened the northern boundaries of the city and added a new and separately walled southern district. Upon the southern extension of the Taiye Lake (the present Nanhai), the raising of Wansui Hill over Yuan ruins, and the completion of the Forbidden City to its south, he declared the city his northern capital Beijing. With one brief interruption, it has borne the name ever since.

Legacy[edit]

Ruins of the Yuan-era walls of Khanbaliq are still extant and are known as the Tucheng (土城), lit. "earth wall".[18] Tucheng Park preserves part of the old northern walls, along with some modern statues.

Despite the capture and renaming of the city by the Ming, the name Daidu[19] remained in use among the Mongols of the Mongolia-based Northern Yuan dynasty.[20] The lament of the last Yuan emperor, Toghon Temür, concerning the loss of Khanbaliq and Shangdu, is recorded in many Mongolian historical chronicles such as the Altan Tobchi and the Asarayci Neretu-yin Teuke.[19]

Khanbaliq remained the standard name for Beijing in Persian and the Turkic languages of Central Asia and the Middle East for quite a long time. It was, for instance, the name used in both the Persian and Turkic versions of Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh's account of the 1419–22 mission of Shah Rukh's envoys to the Ming capital. The account remained one of the most detailed and widely read accounts of China in these languages for centuries.[21]

When European travelers reached China by sea via Malacca and the Philippines in the 16th century, they were not initially aware that China was the same country as the "Cathay" about which they had read in Marco Polo nor that his "Cambaluc" was the city known to the southern Chinese as Pekin. It was not until the Jesuit Matteo Ricci's first visit to Beijing in 1598 that he encountered Central Asian visitors ("Arabian Turks, or Mohammedans" in his description[22]) who confirmed that the city they were in was "Cambaluc." The publication of his journals by his aide announced to Europe that "Cathay" was China and "Cambaluc" Beijing. The journal then fancifully explained that name was "partly of Chinese and partly of Tartar origin", from "Tartar" cam ("great"), Chinese ba ("north"), and Chinese Lu (used for nomads in Chinese literature).[23] Many European maps continued to show "Cathay" and its capital "Cambaluc" somewhere in northeast China for much of the 17th century.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Masuya Tomoko, "Seasonal capitals with permanent buildings in the Mongol empire", in Durand-Guédy, David (ed.), Turko-Mongol Rulers, Cities and City Life, Leiden, Brill, p. 236.

- ^ Brill, E.J. Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 4, pp. 898 ff. "Khānbāliķ". Accessed 17 November 2013.

- ^ Brill, Vol. 2, p. 620. "Bāliķ". Accessed 17 November 2013.

- ^ Rossabi, Morris, Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, p 131

- ^ Herbert Franke, John K. Fairbank (1994). Alien Regimes and Border States. Vol. 6. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 454.

- ^ Vogel, Hans. Marco Polo Was in China: New Evidence from Currencies, Salts, and Revenues, p. 121. Brill, 2012. Accessed 18 November 2013.

- ^ China Archaeology & Art Digest, Vol. 4, No. 2-3. Art Text (HK) Ltd. 2001. p. 35.

- ^ Steinhardt, Nancy Riva Shatzman (1981). Imperial Architecture under Mongolian Patronage: Khubilai's Imperial City of Daidu. Harvard University. p. 222.

The planning of the Imperial City, along with many other imperial projects of the 1260s, was supervised by Khubilai's close minister Liu Bingzhong. That the Imperial City was Chinese in style was certainly Liu's preference...

- ^ Stephen G. Haw (2006). Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the realm of Khubilai Khan. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 0-415-34850-1.

Liu Bingzhong was also charged with overseeing the construction of the Great Khan's other new capital, the city of Dadu.

- ^ The People's Daily Online. "The Hui Ethnic Minority".

- ^ 《明史紀事本末》. "綱鑑易知錄", Roll 8. (in Chinese)

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica (Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago University of, William Benton, Encyclopædia Britannica), p 2

- ^ Chua, Amy (2007). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-385-51284-8. OCLC 123079516.

- ^ Chua, Amy (2007). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-385-51284-8. OCLC 123079516.

- ^ a b Chua, Amy (2007). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-385-51284-8. OCLC 123079516.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge Univ. Press (Cambridge), 1999. ISBN 0-521-66991-X.

- ^ Naquin, Susan. Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400–1900, p. xxxiii.

- ^ "Beijing This Month - Walk the Ancient Dadu City Wall Archived 2008-10-20 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ a b Amitai-Preiss, Reuven & al. The Mongol Empire & Its Legacy, p. 277.

- ^ Norman, Alexander. Holder of the White Lotus. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-85988-2.

- ^ Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (1995), A History of Cathay: a Translation and Linguistic Analysis of a Fifteenth-Century Turkic Manuscript, Bloomington: Indiana University Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, pp. 3–6, 140, ISBN 0-933070-37-3.

- ^ Louis J. Gallagher's translation.

- ^ Trigault, Nicolas. De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas (in Latin). Translated by Louis J. Gallagher as China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583–1610, Book IV, Chap. 3 "Failure at Pekin", pp. 312 ff. Random House (New York), 1953.

External links[edit]

- Yule, Henry (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. IV (9th ed.). pp. 722–723.