Chlamydomonas

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2011) |

| Chlamydomonas | |

|---|---|

| |

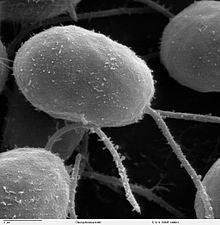

| SEM image of flagellated Chlamydomonas - Genus of Algae (10,000×) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Viridiplantae |

| Division: | Chlorophyta |

| Class: | Chlorophyceae |

| Order: | Chlamydomonadales |

| Family: | Chlamydomonadaceae |

| Genus: | Chlamydomonas Ehrenb. |

| Species | |

| See text | |

Chlamydomonas (/ˌklæmɪˈdɒmənəs, -dəˈmoʊ-/ KLAM-ih-DOM-ə-nəs, -də-MOH-) is a genus of green algae consisting of about 150 species[2] of unicellular flagellates, found in stagnant water and on damp soil, in freshwater, seawater, and even in snow as "snow algae".[3] Chlamydomonas is used as a model organism for molecular biology, especially studies of flagellar motility and chloroplast dynamics, biogenesis, and genetics. One of the many striking features of Chlamydomonas is that it contains ion channels (channelrhodopsins) that are directly activated by light. Some regulatory systems of Chlamydomonas are more complex than their homologs in Gymnosperms, with evolutionarily related regulatory proteins being larger and containing additional domains.[4]

Molecular phylogeny studies indicated that the traditional genus Chlamydomonas as defined using morphological data, was polyphyletic within Volvocales. Many species were subsequently reclassified (e.g., Oogamochlamys, Lobochlamys), and many other "Chlamydomonas" s.l. lineages are still to be reclassified.[5][6][7]

Etymology[edit]

The name Chlamydomonas comes from the Greek roots chlamys, meaning cloak or mantle, and monas, meaning solitary, now used conventionally for unicellular flagellates.[8]

Description[edit]

Morphology[edit]

All Chlamydomonas are motile, unicellular organisms. Cells are generally spherical to cylindrical in shape, but may be elongately spindle-shaped,[9] and a papilla may be present or absent. Chloroplasts are green and usually cup-shaped.[10] A key feature of the genus is its two anterior flagella, each as long as the other.[8] The flagellar microtubules may each be disassembled by the cell to provide spare material to rebuild the other's microtubules if they are damaged.[11]

- Cell wall is made up of a glycoprotein and non-cellulosic polysaccharides instead of cellulose.

- Two anteriorly inserted whiplash flagella. Each flagellum originates from a basal granule in the anterior papillate or non-papillate region of the cytoplasm. Each flagellum shows a typical 9+2 arrangement of the component fibrils.

- Contractile vacuoles are near the bases of flagella.

- Prominent cup or bowl-shaped chloroplast is present. The chloroplast contains bands composed of a variable number of the photosynthetic thylakoids which are not organised into grana-like structures.

- The nucleus is enclosed in a cup-shaped chloroplast, which has a single large pyrenoid where starch is formed from photosynthetic products. Pyrenoid with starch sheath is present in the posterior end of the chloroplast.

- Eye spot present in the anterior portion of the chloroplast. It consists of two or three, more or less parallel rows of linearly arranged fat droplets.

Species[edit]

About 500 species of Chlamydomonas have been described.[9]

- Chlamydomonas acidophila

- Chlamydomonas caudata Wille

- Chlamydomonas ehrenbergii Gorozhankin[10]

- Chlamydomonas elegans G.S.West 1915

- Chlamydomonas moewusii

- Chlamydomonas muriella J.W.G.Lund 1947

- Chlamydomonas nivalis

- Chlamydomonas ovoidae

- Chlamydomonas priscuii

- Chlamydomonas smithii[12]

- Chlamydomonas reinhardtii[13]

Ecology[edit]

Chlamydomonas is widely distributed in freshwater or damp soil.[2] It is generally found in a habitat rich in ammonium salt. It possesses red eye spots for photosensitivity and reproduces both asexually and sexually.

Chlamydomonas's asexual reproduction occurs by zoospores, aplanospores, hypnospores, or a palmella stage,[14] while its sexual reproduction is through isogamy, anisogamy or oogamy.

Nutrition[edit]

Most species are obligate phototrophs but C. reinhardtii and C. dysostosis are facultative heterotrophs that can grow in the dark in the presence of acetate as a carbon source.

Uses[edit]

Some Chlamydomonas are edible.[15]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Hazen, Tracy E. 1922. The phylogeny of the genus Brachiomonas. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 49(4):75-92, with two plates.

- ^ a b Smith, G. M. 1955 Cryptogamic Botany Volume 1. Algae and Fungi McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc

- ^ Hoham, R. W., Bonome, T. A., Martin, C. W. and Leebens-mack, J. H. 2002. A combined 18S rDNA and rbcL phylogenetic analysis of Chloromonas and Chlamydomonas (Chlorophyceae, Volvocales ) emphasizing snow and other cold-temperature habitats. Journal of Phycology, 38: 1051–1064. [1]

- ^ A Falciatore, L Merendino, F Barneche, M Ceol, R Meskauskiene, K Apel, JD Rochaix (2005). The FLP proteins act as regulators of chlorophyll synthesis in response to light and plastid signals in Chlamydomonas. The red eyespot in Chlamydomonas is sensitive to light and hence determines movement. Genes & Dev, 19:176-187 [2]

- ^ Juliet Brodie & Jane Lewis (2007). Unravelling the algae: the past, present, and future of algal systematics. CRC Press. p. 140, [3].

- ^ Wehr, J.D., Sheath, R.G. & Kociolek, J.P. (eds., 2015). Freshwater Algae of North America: Ecology and Classification. Academic Press, USA, p. 275-276, [4].

- ^ Proschold, T.; Marin, B.; Schlösser, U. G.; Melkonian, M. (2001). "Molecular phylogeny and taxonomic revision of (Chlorophyta). I. Emendation of Chlamydomonas Ehrenberg and Chloromonas Gobi, and Description of Oogamochlamys gen. nov. and Lobochlamys gen. nov". Protist. 152 (4): 265–300. doi:10.1078/1434-4610-00068. PMID 11822658.

- ^ a b Harris, Elizabeth H. ( 2009) "The Genus Chlamydomonas" In The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook (Second Edition), chapter 1, volume 1, pages 1-24. ISBN 9780080919553 doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-370873-1.00001-0

- ^ a b Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. "Chlamydomonas". AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

- ^ a b Guiry, M.D., John, D.M. Rindi, F. and McCarthy, T.K. (ed) 2007 New Survey of Clare Island Volume 6: The Freshwater and Terrestrial Algae. Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 978-1-904890-31-7

- ^ Gelfand, Vladimir I.; Bershadsky, Alexander D. (1991). "Microtubule Dynamics: Mechanism, Regulation, and Function". Annual Review of Cell Biology. 7 (1). Annual Reviews: 93–116. doi:10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.000521. ISSN 0743-4634. PMID 1809357.

- ^ Hoshaw, Robert W.; Ettl, H. (September 1966). "Chlamydomonas smithii sp. nov.?A Chlamydomonad Interfertile with Chlamydomonas Reinhardtip". Journal of Phycology. 2 (3): 93–96. Bibcode:1966JPcgy...2...93H. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.1966.tb04600.x. PMID 27053409. S2CID 30987145.

- ^ Aoyama, H., Kuroiwa, T and Nakamura,S. 2009. The dynamic behaviour of mitochrandia in living zygotes during maturation and meiosis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. European Journal Phycology 44: 497 - 507

- ^ "Life Cycle of Chlamydomonas (With Diagram)". BiologyDiscussion.com. 2016-09-16. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Notice to US Food and Drug Administration of the Conclusion that the Intended Use of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (THN 6) Dried Biomass Powder is Generally Recognized as Safe". US Food and Drug Administration. March 21, 2018.

External links[edit]

- Chlamydomonas Center

- Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Transcription Factor Database Archived 2009-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- 3D electron microscopy structures of Chlamydomonas-related proteins at the EM Data Bank(EMDB)

- The Seaweed Site

- Ancient gene family protects algae from salt and cold in an Antarctic lake, on: EurekAlert!, 20-Aug-2020, on species UWO241 and ICE-MDV in Lake Bonney (Antarctica)