Criticism of advertising

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (September 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Anti-consumerism |

|---|

Advertising is a form of selling a product to a certain audience in which communication is intended to persuade an audience to purchase products, ideals or services regardless of whether they want or need them. While advertising can be seen as a way to inform the audience about a certain product or idea it also comes with a cost because the sellers have to find a way to show the seller interest in their product. It is not without social costs. Unsolicited commercial email and other forms of spam have become so prevalent that they are a major nuisance to internet users, as well as being a financial burden on internet service providers.[1] Advertising increasingly invades public spaces, such as schools, which some critics argue is a form of child exploitation.[2] Advertising frequently uses psychological pressure (for example, appealing to feelings of inadequacy) on the intended consumer, which may be harmful. As a result of these criticisms, the advertising industry has seen low approval rates in surveys and negative cultural portrayals.[3]

Criticism of advertising is closely linked with criticism of media and often interchangeable. Critics can refer to advertising's:

- audio-visual aspects (cluttering of public spaces and airwaves)

- environmental aspects (pollution, oversize packaging, increasing consumption)

- political aspects (media dependency, free speech, censorship)

- financial aspects (costs)

- time-consuming aspects

- social/moral/ethical aspects (sub-conscious influencing, invasion of privacy, increasing consumption and waste, target groups, certain products, honesty)

Hyper-commercialism[edit]

As advertising has become prevalent in modern society, it is increasingly being criticized. Advertising occupies public space and more and more invades the private sphere of people. According to Georg Franck, "It is becoming harder to escape from advertising and the media. Public space is increasingly turning into a gigantic billboard for products of all kinds. The aesthetical and political consequences cannot yet be foreseen."[5] Hanno Rauterberg in the German newspaper Die Zeit calls advertising a new kind of dictatorship that cannot be escaped.[6]

Discussing ad creep, Commercial Alert says, "There are ads in schools, airport lounges, doctors offices, movie theaters, hospitals, gas stations, elevators, convenience stores, on the Internet, on fruit, on ATMs, on garbage cans and countless other places. There are ads on beach sand and restroom walls."[7] "One of the ironies of advertising in our times is that as commercialism increases, it makes it that much more difficult for any particular advertiser to succeed, hence pushing the advertiser to even greater efforts."[8] Within a decade, advertising on radio climbed to nearly 18 or 19 minutes per hour.[when?] On prime-time television, the standard until 1982 was no more than 9.5 minutes of advertising per hour, but today it is between 14 and 17 minutes. With the introduction of the shorter 15-second-spot the total amount of ads increased even more.[citation needed] Ads are not only placed in breaks but also into sports telecasts during the game itself. They flood the Internet, a growing market.

Other growing markets are product placements in entertainment programming and movies, where it has become standard practice and virtual advertising, where products get placed retroactively into rerun shows. Product billboards are virtually inserted into Major League Baseball broadcasts and in the same manner, virtual street banners or logos are projected on an entry canopy or sidewalks, for example during the arrival of celebrities at the 2001 Grammy Awards. Advertising precedes the showing of films at cinemas including lavish 'film shorts' produced by companies such as Microsoft or DaimlerChrysler. "The largest advertising agencies have begun working to co-produce programming in conjunction with the largest media firms",[9] creating Infomercials resembling entertainment programming.

Opponents equate the growing amount of advertising with a "tidal wave" and restrictions with "damming" the flood. Kalle Lasn, one of the most outspoken critics of advertising, considers advertising "the most prevalent and toxic of the mental pollutants. From the moment your radio alarm sounds in the morning to the wee hours of late-night TV microjolts of commercial pollution flood into your brain at the rate of around 3,000 marketing messages per day. Every day an estimated 12 billion display ads, 3 million radio commercials and more than 200,000 television commercials are dumped into North America's collective unconscious".[10] In the course of their life, the average American watches three years of advertising on television.[11]

Video games incorporate products into their content. Special commercial patient channels in hospitals and public figures sporting temporary tattoos. A method unrecognisable as advertising is so-called guerrilla marketing which is spreading 'buzz' about a new product in target audiences. Cash-strapped U.S. cities offer police cars for advertising.[12] Companies buy the names of sports stadiums for advertising. The Hamburg soccer Volkspark stadium first became the AOL Arena and then the HSH Nordbank Arena. The Stuttgart Neckarstadion became the Mercedes-Benz Arena, the Dortmund Westfalenstadion is the Signal Iduna Park. The former SkyDome in Toronto was renamed Rogers Centre.

Whole subway stations in Berlin are redesigned into product halls and exclusively leased to a company. Düsseldorf has "multi-sensorial" adventure transit stops equipped with loudspeakers and systems that spread the smell of a detergent. Swatch used beamers to project messages on the Berlin TV-tower and Victory column, which was fined because it was done without a permit. The illegality was part of the scheme and added promotion.[6] Christopher Lasch states that advertising leads to an overall increase in consumption in society; "Advertising serves not so much to advertise products as to promote consumption as a way of life."[13]

Fully unsolicited advertisements, where the recipients have not consented and are provided nothing in return, have been singled out for particular criticism as instances of attention theft.[4]

Constitutional rights[edit]

In the US, advertising is equated with constitutionally guaranteed freedom of opinion and speech.[14]

Currently or in the near future, any number of cases are and will be working their way through the court system that would seek to prohibit any government regulation of ... commercial speech (e.g. advertising or food labelling) on the grounds that such regulation would violate citizens' and corporations' First Amendment rights to free speech or free press.[15]

An example for this debate is advertising for tobacco or alcohol but also advertising by mail or fliers (clogged mail boxes), advertising on the phone, on the Internet and advertising for children. Various legal restrictions concerning spamming, advertising on mobile phones, when addressing children, tobacco and alcohol have been introduced by the US, the EU and other countries.

McChesney argues that the government deserves constant vigilance when it comes to such regulations, but that it is certainly not "the only antidemocratic force in our society. Corporations and the wealthy enjoy a power every bit as immense as that enjoyed by the lords and royalty of feudal times" and "markets are not value-free or neutral; they not only tend to work to the advantage of those with the most money, but they also by their very nature emphasize profit over all else. Hence, today the debate is over whether advertising or food labelling, or campaign contributions are speech ... if the rights to be protected by the First Amendment can only be effectively employed by a fraction of the citizenry, and their exercise of these rights gives them undue political power and undermines the ability of the balance of the citizenry to exercise the same rights and/or constitutional rights, then it is not necessarily legitimately protected by the First Amendment". "Those with the capacity to engage in free press are in a position to determine who can speak to the great mass of citizens and who cannot".[16]

Georg Franck at Vienna University of Technology, says that advertising is part of what he calls "mental capitalism",[5][17] taking up a term (mental) which has been used by groups concerned with the mental environment, such as Adbusters. Franck blends the "Economy of Attention" with Christopher Lasch's culture of narcissism into the mental capitalism:[18] In his essay "Advertising at the Edge of the Apocalypse", Sut Jhally writes: "20th century advertising is the most powerful and sustained system of propaganda in human history and its cumulative cultural effects, unless quickly checked, will be responsible for destroying the world as we know it."[19]

Costs[edit]

Advertising has developed into a multibillion-dollar business. In 2014, 537 billion US dollars [20] were spent worldwide for advertising. In 2013, TV accounted for 40.1% of ad spending, compared to a combined 18.1% for internet, 16.9% for newspapers, 7.9% for magazines, 7% for outdoor, 6.9% for radio, 2.7% for mobile and 0.5% for cinema as a share of ad spending by medium. Advertising is considered to raise consumption.

Attention and attentiveness have become a new commodity for which a market developed. "The amount of attention that is absorbed by the media and redistributed in the competition for quotas and reach is not identical with the amount of attention, that is available in society. The total amount circulating in society is made up of the attention exchanged among the people themselves and the attention given to media information. Only the latter is homogenised by quantitative measuring and only the latter takes on the character of an anonymous currency."[5][17] According to Franck, any surface of presentation that can guarantee a certain degree of attentiveness works as a magnet for attention, for example, media which are actually meant for information and entertainment, culture and the arts, public space etc. It is this attraction which is sold to the advertising business. In Germany, the advertising industry contributes 1.5% of the gross national income. The German Advertising Association stated that in 2007, 30.78 billion Euros were spent on advertising in Germany,[21] 26% in newspapers, 21% on television, 15% by mail and 15% in magazines. In 2002 there were 360,000 people employed in the advertising business. The Internet revenues for advertising doubled to almost 1 billion Euros from 2006 to 2007, giving it the highest growth rates.

Few consumers are aware of the fact that they are the ones paying for every cent spent for public relations, advertisements, rebates, packaging etc., since they ordinarily get included in the price calculation.[citation needed]

In 2021-22, advertisers and agencies raised concerns about the excessive volume of work and associated pressures entailed in making sales pitches for advertising opportunities. Criticisms raised argued that pitches were being requested unnecessarily often and their production being made too complex and too costly. The Pitch Positive Pledge was adopted as a result, according to which industry players would ensure a pitch was actually required before proceeding, "run a positive pledge" and "provide a positive resolution". Feedback to unsuccessful bidders is a key element of this process.[22][23]

Influence[edit]

The most important element of advertising is not information but suggestion – more or less making use of associations, emotions and drives in the subconscious, such as sex drive, herd instinct, desires such as happiness, health, fitness, appearance, self-esteem, reputation, belonging, social status, identity, adventure, distraction, reward, fears such as illness, weaknesses, loneliness, need, uncertainty, security or of prejudices, learned opinions and comforts. "All human needs, relationships, and fears – the deepest recesses of the human psyche – become mere means for the expansion of the commodity universe under the force of modern marketing. With the rise to prominence of modern marketing, commercialism – the translation of human relations into commodity relations – although a phenomenon intrinsic to capitalism, has expanded exponentially."[24] Cause-related marketing in which advertisers link their product to some worthy social cause has boomed over the past decade.

Advertising uses the model role of celebrities or popular figures and makes deliberate use of humor as well as of associations with color, tunes, certain names and terms. These are factors of how one perceives oneself and one's self-worth. In his description of 'mental capitalism' Franck says, "the promise of consumption making someone irresistible is the ideal way of objects and symbols into a person's subjective experience. Evidently, in a society in which revenue of attention moves to the fore, consumption is drawn by one's self-esteem. As a result, consumption becomes 'work' on a person's attraction. From the subjective point of view, this 'work' opens fields of unexpected dimensions for advertising. Advertising takes on the role of a life councillor in matters of attraction. The cult around one's own attraction is what Christopher Lasch described as 'Culture of Narcissism'."[17][18]

For advertising critics another serious problem is that, "the long standing notion of separation between advertising and editorial/creative sides of media is rapidly crumbling" and advertising is increasingly hard to tell apart from news, information or entertainment. The boundaries between advertising and programming are becoming blurred. According to the media firms all this commercial involvement has no influence over actual media content, but as McChesney puts it, "this claim fails to pass even the most basic giggle test, it is so preposterous."[25]

Advertising draws "heavily on psychological theories about how to create subjects, enabling advertising and marketing to take on a 'more clearly psychological tinge'.[26] Increasingly, the emphasis in advertising has switched from providing 'factual' information to the symbolic connotations of commodities, since the crucial cultural premise of advertising is that the material object being sold is never in itself enough. Even those commodities providing for the most mundane necessities of daily life must be imbued with symbolic qualities and culturally endowed meanings via the 'magic system' of advertising.[27] In this way and by altering the context in which advertisements appear, things 'can be made to mean 'just about anything' and the 'same' things can be endowed with different intended meanings for different individuals and groups of people, thereby offering mass produced visions of individualism."[28][29]

Before advertising is done, market research institutions need to know and describe the target group to exactly plan and implement the advertising campaign and to achieve the best possible results. A whole array of sciences directly deal with advertising and marketing or are used to improve its effects. Focus groups, psychologists and cultural anthropologists are de rigueur in marketing research".[30] Vast amounts of data on persons and their shopping habits are collected, accumulated, aggregated and analysed with the aid of credit cards, bonus cards, raffles and internet surveying. With increasing accuracy this supplies a picture of behaviour, wishes and weaknesses of certain sections of a population with which advertisement can be employed more selectively and effectively.

The efficiency of advertising is improved through advertising research. Universities, of course supported by business and in co-operation with other disciplines (s. above), mainly Psychiatry, Anthropology, Neurology and behavioural sciences, are constantly in search for ever more refined, sophisticated, subtle and crafty methods to make advertising more effective. "Neuromarketing is a controversial new field of marketing which uses medical technologies such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)—not to heal, but to sell products. Advertising and marketing firms have long used the insights and research methods of psychology in order to sell products, of course. But today these practices are reaching epidemic levels, and with a complicity on the part of the psychological profession that exceeds that of the past. The result is an enormous advertising and marketing onslaught that comprises, arguably, the largest single psychological project ever undertaken. Yet, this great undertaking remains largely ignored by the American Psychological Association."[31] Robert McChesney calls it "the greatest concerted attempt at psychological manipulation in all of human history."[32]

Media and corporate censorship[edit]

Almost all mass media are advertising media and many of them are exclusively advertising media and, with the exception of public service broadcasting, are in the private sector. Their income is predominantly generated through advertising; in the case of newspapers and magazines from 50 to 80%. Public service broadcasting in some countries can also heavily depend on advertising as a source of income (up to 40%).[33] In the view of critics no media that spreads advertisements can be independent and the higher the proportion of advertising, the higher the dependency. This dependency has "distinct implications for the nature of media content. ... In the business press, the media are often referred to in exactly the way they present themselves in their candid moments: as a branch of the advertising industry."[34]

In addition, the private media are increasingly subject to mergers and concentration with property situations often becoming entangled and opaque. This development, which Henry A. Giroux calls an "ongoing threat to democratic culture",[35] by itself should suffice to sound all alarms in a democracy. Five or six advertising agencies dominate this 400 billion U.S. dollar global industry.

"Journalists have long faced pressure to shape stories to suit advertisers and owners ... the vast majority of TV station executives found their news departments 'cooperative' in shaping the news to assist in 'non-traditional revenue development."[36]

Negative and undesired reporting can be prevented or influenced when advertisers threaten to cancel orders or simply when there is a danger of such a cancellation. Media dependency and such a threat become very real when there is only one dominant or very few large advertisers. The influence of advertisers is not only in regard to news or information on their own products or services but expands to articles or shows not directly linked to them. In order to secure their advertising revenues the media have to create the best possible 'advertising environment'.

Another problem considered censorship by critics is the refusal of media to accept advertisements that are not in their interest. A striking example of this is the refusal of TV stations to broadcast ads by Adbusters. Groups try to place advertisements and are refused by networks.[37]

It is principally the viewing rates which decide upon the programme in the private radio and television business. "Their business is to absorb as much attention as possible. The viewing rate measures the attention the media trades for the information offered. The service of this attraction is sold to the advertising business"[17] and the viewing rates determine the price that can be demanded for advertising.

While critics basically worry about the subtle influence of the economy on the media, there are also examples of blunt exertion of influence. The US company Chrysler, before it merged with Daimler Benz had its agency (PentaCom) send out a letter to numerous magazines, demanding that they send an overview of all the topics before the next issue was published, to "avoid potential conflict". Chrysler most of all wanted to know if there would be articles with "sexual, political or social" content, or which could be seen as "provocative or offensive". PentaCom executive David Martin said: "Our reasoning is, that anyone looking at a 22.000 $ product would want it surrounded by positive things. There is nothing positive about an article on child pornography."[38] In another example, the USA Network held top-level‚ off-the-record meetings with advertisers in 2000 to let them tell the network what type of programming content they wanted in order for USA to get their advertising."[39] Television shows are created to accommodate the needs of advertising, e.g. splitting them up in suitable sections. Their dramaturgy is typically designed to end in suspense or leave an unanswered question in order to keep the viewer attached.

The movie system, at one time outside the direct influence of the broader marketing system, is now fully integrated into it through the strategies of licensing, tie-ins and product placements. The prime function of many Hollywood films today is to aid in the selling of the immense collection of commodities.[40] The press called the 2002 Bond film 'Die Another Day' featuring 24 major promotional partners an 'ad-venture' and noted that James Bond "now has been 'licensed to sell'". As it has become standard practice to place products in motion pictures, it "has self-evident implications for what types of films will attract product placements and what types of films will therefore be more likely to get made".[41]

Advertising and information are increasingly hard to distinguish from each other. "The borders between advertising and media ... become more and more blurred. ... What August Fischer, chairman of the board of Axel Springer publishing company considers to be a 'proven partnership between the media and advertising business' critics regard as nothing but the infiltration of journalistic duties and freedoms". According to RTL Group former executive Helmut Thoma "private stations shall not and cannot serve any mission but only the goal of the company which is the 'acceptance by the advertising business and the viewer'. The setting of priorities in this order actually says everything about the 'design of the programmes' by private television."[38] Patrick Le Lay, former managing director of TF1, a private French television channel with a market share of 25 to 35%, said: "There are many ways to talk about television. But from the business point of view, let's be realistic: basically, the job of TF1 is, e. g. to help Coca Cola sell its product. ... For an advertising message to be perceived the brain of the viewer must be at our disposal. The job of our programmes is to make it available, that is to say, to distract it, to relax it and get it ready between two messages. It is disposable human brain time that we sell to Coca Cola."[42]

Because of these dependencies, a widespread and fundamental public debate about advertising and its influence on information and freedom of speech is difficult to obtain, at least through the usual media channels: it would saw off the branch it was sitting on. "The notion that the commercial basis of media, journalism, and communication could have troubling implications for democracy is excluded from the range of legitimate debate" just as "capitalism is off-limits as a topic of legitimate debate in US political culture".[43]

An early critic of the structural basis of US journalism was Upton Sinclair with his novel The Brass Check in which he stresses the influence of owners, advertisers, public relations, and economic interests on the media. In his book Our Master's Voice: Advertising the social ecologist James Rorty (1890–1973) wrote:[44]

The gargoyle's mouth is a loudspeaker, powered by the vested interest of a two-billion dollar industry, and back of that the vested interests of business as a whole, of industry, of finance. It is never silent, it drowns out all other voices, and it suffers no rebuke, for it is not the voice of America? That is its claim and to some extent it is a just claim... It has taught us how to live, what to be afraid of, what to be proud of, how to be beautiful, how to be loved, how to be envied, how to be successful.. Is it any wonder that the American population tends increasingly to speak, think, feel in terms of this jabberwocky? That the stimuli of art, science, religion are progressively expelled to the periphery of American life to become marginal values, cultivated by marginal people on marginal time?

Culture and sports[edit]

Performances, exhibitions, shows, concerts, conventions and most other events can hardly take place without sponsoring.[citation needed] Artists are graded and paid according to their art's value for commercial purposes. Corporations promote renowned artists, thereby getting exclusive rights in global advertising campaigns. Broadway shows like La Bohème featured commercial props in their sets.[45]

Advertising itself is extensively considered to be a contribution to culture. Advertising is integrated into fashion. On many pieces of clothing the company logo is the only design or is an important part of it. There is only a little room left outside the consumption economy, in which culture and art can develop independently and where alternative values can be expressed. A last important sphere, the universities, is under strong pressure to open up for business and its interests.[46]

Competitive sports have become unthinkable without sponsoring and there is a mutual dependency.[citation needed] High income with advertising is only possible with a comparable number of spectators or viewers. On the other hand, the poor performance of a team or a sportsman results in less advertising revenues. Jürgen Hüther and Hans-Jörg Stiehler talk about a 'Sports/Media Complex which is a complicated mix of media, agencies, managers, sports promoters, advertising etc. with partially common and partially diverging interests but in any case with common commercial interests. The media presumably is at centre stage because it can supply the other parties involved with a rare commodity, namely (potential) public attention. In sports "the media are able to generate enormous sales in both circulation and advertising."[47]

"Sports sponsorship is acknowledged by the tobacco industry to be valuable advertising. A Tobacco Industry journal in 1994 described the Formula One car as 'The most powerful advertising space in the world'. ... In a cohort study carried out in 22 secondary schools in England in 1994 and 1995 boys whose favourite television sport was motor racing had a 12.8% risk of becoming regular smokers compared to 7.0% of boys who did not follow motor racing."[48]

Not the sale of tickets but transmission rights, sponsoring and merchandising in the meantime make up the largest part of sports association's and sports club's revenues with the IOC (International Olympic Committee) taking the lead. The influence of the media brought many changes in sports including the admittance of new 'trend sports' into the Olympic Games, the alteration of competition distances, changes of rules, animation of spectators, changes of sports facilities, the cult of sports heroes who quickly establish themselves in the advertising and entertaining business because of their media value[49] and last but not least, the naming and renaming of sport stadiums after big companies.

"In sports adjustment into the logic of the media can contribute to the erosion of values such as equal chances or fairness, to excessive demands on athletes through public pressure and multiple exploitation or to deceit (doping, manipulation of results ...). It is in the very interest of the media and sports to counter this danger because media sports can only work as long as sport exists.[49]

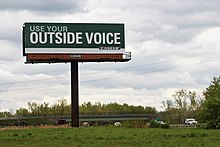

Public space[edit]

Every visually perceptible place has potential for advertising, especially urban areas with their structures but also landscapes in sight of thoroughfares are more and more turning into media for advertisements. Signs, posters, billboards, flags have become decisive factors in the urban appearance and their numbers are still on the increase. "Outdoor advertising has become unavoidable. Traditional billboards and transit shelters have cleared the way for more pervasive methods such as wrapped vehicles, sides of buildings, electronic signs, kiosks, taxis, posters, sides of buses, and more. Digital technologies are used on buildings to sport 'urban wall displays'. In urban areas commercial content is placed in our sight and into our consciousness every moment we are in public space. The German newspaper Zeit called it a new kind of "dictatorship that one cannot escape".[6]

Over time, this domination of the surroundings has become the "natural" state. Through long-term commercial saturation, it has become implicitly understood by the public that advertising has the right to own, occupy and control every inch of available space. The steady normalization of invasive advertising dulls the public's perception of their surroundings, re-enforcing a general attitude of powerlessness toward creativity and change, thus a cycle develops enabling advertisers to slowly and consistently increase the saturation of advertising with little or no public outcry."[50]

The massive optical orientation toward advertising changes the function of public spaces which are utilised by brands. Urban landmarks are turned into trademarks. The highest pressure is exerted on renown and highly frequented public spaces which are also important for the identity of a city (e.g. Piccadilly Circus, Times Square, Alexanderplatz). Urban spaces are public commodities and in this capacity they are subject to "aesthetical environment protection", mainly through building regulations, heritage protection and landscape protection. "It is in this capacity that these spaces are now being privatised. They are peppered with billboards and signs, they are remodelled into media for advertising."[5][17]

Sexism, discrimination and stereotyping[edit]

"Advertising has an "agenda setting function" which is the ability, with huge sums of money, to put consumption as the only item on the agenda. In the battle for a share of the public conscience this amounts to non-treatment (ignorance) of whatever is not commercial and whatever is not advertised for.

With increasing force, advertising makes itself comfortable in the private sphere so that the voice of commerce becomes the dominant way of expression in society."[51] Advertising critics see advertising as the leading light in our culture. Sut Jhally and James Twitchell go beyond considering advertising as kind of religion and that advertising even replaces religion as a key institution.[52]

"Corporate advertising (or commercial media) is the largest single psychological project ever undertaken by the human race. Yet for all of that, its impact on us remains unknown and largely ignored. When I think of the media's influence over years, over decades, I think of those brainwashing experiments conducted by Dr. Ewen Cameron in a Montreal psychiatric hospital in the 1950s (see MKULTRA). The idea of the CIA-sponsored "depatterning" experiments was to outfit conscious, unconscious or semiconscious subjects with headphones, and flood their brains with thousands of repetitive "driving" messages that would alter their behaviour over time. ... Advertising aims to do the same thing."[10]

Advertising is especially aimed at young people and children and it increasingly reduces young people to consumers.[35] For Sut Jhally it is not "surprising that something this central and with so much being expended on it should become an important presence in social life. Indeed, commercial interests intent on maximizing the consumption of the immense collection of commodities have colonized more and more of the spaces of our culture. For instance, almost the entire media system (television and print) has been developed as a delivery system for marketers, and its prime function is to produce audiences for sale to advertisers. Both the advertisements it carries and the editorial matter that acts as a support for it celebrate the consumer society. The movie system, at one time outside the direct influence of the broader marketing system, is now fully integrated into it through the strategies of licensing, tie-ins and product placements.

The prime function of many Hollywood films today is to aid in the selling of the immense collection of commodities. As public funds are drained from the non-commercial cultural sector, art galleries, museums and symphonies bid for corporate sponsorship."[40] In the same way affected is the education system and advertising is increasingly penetrating schools and universities. Cities, such as New York, accept sponsors for public playgrounds. "Even the pope has been commercialized ... The pope's four-day visit to Mexico in ... 1999 was sponsored by Frito-Lay and PepsiCo.[53] The industry is accused of being one of the engines powering a convoluted economic mass production system which promotes consumption. As far as social effects are concerned it does not matter whether advertising fuels consumption but which values, patterns of behaviour and assignments of meaning it propagates.

Advertising is accused of hijacking the language and means of pop culture, of protest movements and even of subversive criticism and does not shy away from scandalizing and breaking taboos (e.g. Benetton). This in turn incites counter action, what Kalle Lasn in 2001 called Jamming the Jam of the Jammers. Anything goes. "It is a central social-scientific question what people can be made to do by suitable design of conditions and of great practical importance. For example, from a great number of psychological experiments it can be assumed, that people can be made to do anything they are capable of, when the according social condition can be created."[54]

Advertising often uses stereotype gender specific roles of men and women reinforcing existing clichés and it has been criticized as "inadvertently or even intentionally promoting sexism, racism, heterosexualism, ableism, ageism, et cetera ... At very least, advertising often reinforces stereotypes by drawing on recognizable "types" in order to tell stories in a single image or 30 second time frame." Activities are depicted as typical male or female (stereotyping). In addition, people are reduced to their sexuality or equated with commodities and gender specific qualities are exaggerated. Sexualized female bodies, but increasingly also males, serve as eye-catchers.

In advertising, it is usually a woman that is depicted as

- a servant of men and children that reacts to the demands and complaints of her loved ones with a bad conscience and the promise for immediate improvement (wash, food)

- a sexual or emotional play toy for the self-affirmation of men

- a technically totally clueless being that can only manage a childproof operation

- female expert, but stereotype from the fields of fashion, cosmetics, food or at the most, medicine

- as ultra thin

- doing ground-work for others, e.g. serving coffee while a journalist interviews a politician[55]

A large portion of advertising deals with the promotion of products in a way that defines an "ideal" body image. This objectification greatly affects women; however, men are also affected. Women and men in advertising are frequently portrayed in unrealistic and distorted images that set a standard for what is considered "beautiful", "attractive" or "desirable." Such imagery does not allow for what is found to be beautiful in various cultures or to the individual. It is exclusionary, rather than inclusive, and consequently, these advertisements promote a negative message about body image to the average person. Because of this form of media, girls, boys, women and men may feel under high pressure to maintain an unrealistic and often unhealthy body weight or even to alter their physical appearance cosmetically or surgically in minor to drastic ways.

The EU parliament passed a resolution in 2008 that advertising may not be discriminating and degrading. This shows that politicians are increasingly concerned about the negative impacts of advertising. However, the benefits of promoting overall health and fitness are often overlooked. Men are also negatively portrayed as incompetent and the butt of every joke in advertising.

False statements are often used in advertising to help draw a person's attention. Misleading or deceiving methods of advertising are used by millions of companies such as Volkswagen, Dannon, and Red Bull. According to Business Insider, "In 2015, it was exposed that VW had been cheating emissions test on its diesel cars in the US for the past seven years" [1]. Advertising can also portray individuals provocatively by displaying nude photos or indecent language. As a result, this leads to people not feeling confident about themselves or their body which causes psychological disorders such as depression or anxiety. Your Article Library talks about some of the main criticisms against advertising by stating, "Some advertisements are un-ethical and objectionable ... This adversely affects the social values" 2

Children and adolescents[edit]

Business is interested in children and adolescents because of their buying power and because of their influence on the shopping habits of their parents. As they are easier to influence they are especially targeted by the advertising business.

Children "represent three distinct markets:

- Primary Purchasers ($2.9 billion annually)

- Future Consumers (Brand-loyal adults)

- Purchase Influencers ($20 billion annually)

Kids will carry forward brand expectations, whether positive, negative, or indifferent. Kids are already accustomed to being catered to as consumers. The long term prize: Loyalty of the kid translates into a brand loyal adult customer"[56]

"Kids represent an important demographic to marketers because they have their own purchasing power, they influence their parents' buying decisions and they're the adult consumers of the future."[57] Advertising for other products preferably uses media with which they can also reach the next generation of consumers.[58] "Key advertising messages exploit the emerging independence of young people."

College students tend to fall into student debt due to a simple purchase of a credit card. It first starts with credit card companies targeting college students from the moment they walk onto campus. These companies advertise credit cards by convincing students with pitches, such as the credit cards will be given away for "free" or by giving away items in exchange for a credit card sign-up. An article called "Why Credit Card Companies Target College Students" by The Balance talks about how, "One in 10 college students leaves with over $10,000 in debt." [2]

Children's exposure to advertising[edit]

The children's market, where resistance to advertising is weakest, is the "pioneer for ad creep".[59] One example is product placement. "Product placements show up everywhere, and children aren't exempt. Far from it. The animated film, Foodfight, had 'thousands of products and character icons from the familiar (items) in a grocery store.' Children's books also feature branded items and characters, and millions of them have snack foods as lead characters."[60]

The average Canadian child sees 350,000 TV commercials before graduating from high school, spends nearly as much time watching TV as attending classes. In 1980 the Canadian province of Quebec banned advertising for children under age 13.[61] "In upholding the constitutional validity of the Quebec Consumer Protection Act restrictions on advertising to children under age 13 (in the case of a challenge by a toy company) the Court held: '... advertising directed at young children is per se manipulative. Such advertising aims to promote products by convincing those who will always believe.'"[62] Norway (ads directed at children under age 12), and Sweden (television ads aimed at children under age 12) also have legislated broad bans on advertising to children, during child programmes any kind of advertising is forbidden in Sweden, Denmark, Austria and Flemish Belgium. In Greece there is no advertising for kids products from 7 to 22 h. An attempt to restrict advertising directed at children in the US failed with reference to the First Amendment. In Spain bans are also considered undemocratic.[63][64]

Web sites targeted to children may also display advertisements, though there are fewer ads on non-profit web sites than on for-profit sites and those ads were less likely to contain enticements. However, even ads on non-profit sites may link to sites that collect personal information.[65]

Child social-media advertising[edit]

In 2015, Shion and Loan Kaji built a YouTube channel hosted by their seven-year-old son, Ryan Kaji. Ryan's ToyReviews channel has 21 million subscribers and over 30 billion views. Toy manufacturing companies have donated a large sum of toys for Ryan to review on his channel. Walmart, Hasbro, Netflix, Chuck E. Cheese and Nickelodeon have all sponsored Ryan Kaji and his Ryan ToysReview channel.[66] He has also built a partnership with a child entertainment company Pocket.Watch. Due to the popularity of the show, they were advertised to change the name to Ryan's World. Not only did large companies advise the name change, they encouraged him to provide more content such as, science experiments, challenges and education as well.[67] The expansion of Ryan's World also has led to the production of his very own merchandise. He now produces a clothing line and his own toys sold specifically at Walmart.[68]

Food advertising[edit]

Sweets, ice cream, and breakfast food makers often aim their promotion at children and adolescents. For example, an ad for a breakfast cereal on a channel aimed at adults will have music that is a soft ballad, whereas on a channel aimed at children, the same ad will use a catchy rock jingle of the same song to aim at kids. "The marketing industry is facing increased pressure over claimed links between exposure to food advertising and a range of social problems, especially growing obesity levels."[69] "Fast food chains spend more than 3 billion dollars a year on advertising, much of it aimed at children ... Restaurants offer incentives such as playgrounds, contests, clubs, games, and free toys and other merchandise related to movies, TV shows and even sports leagues."[70] These businesses are constantly reaping the benefits of this child manipulation.

In 2006, 44 of the largest U.S. food industries spent about 2 billion dollars on advertising their products, which mainly consisted of unhealthy, sugary and fatty foods. Such massive advertising has a detrimental effect on children and it heavily influences their diets.[citation needed] Extensive research proves that most of the food consumed between ages of 2–18 is low in nutrients. Facing a lot of pressure from health industries and laws, such as the Children's Food and Beverage Advertising initiative, food marketers were forced to tweak and limit their advertising strategies. Despite regulations, a 2009 report shows that three quarters of all food advertising during children's television programs were outside of the law's boundaries. Government attempts to put a heavy burden on food marketers in order to prevent the issue, but food marketers enjoy the benefits of the First Amendment which limits government's power to prevent advertising against children. The Federal Trade Commission states that children between the ages of 2–11 on average see 15 food based commercials on television daily. Most of these commercial involve high-sugar and high-fat foods, which adds to the problem of childhood obesity. An experiment that took place in a summer camp, where researches showed food advertisements to children between ages 5–8 for two weeks. The outcome-what kids chose to eat at a cafeteria were the ads they saw on TV over the two weeks.[71] Leading back to psychological effects that advertising has on individuals, one of the main important effects is eating disorders among children. An article from the US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health even states that, "Several cross-sectional studies have reported a positive association between exposure to beauty and fashion magazines and an increased level of weight concerns or eating disorder symptoms in girls."[72] Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are some of the common disorders among adolescent girls. The rate of anorexia nervosa among adolescent girls is 0.48%.[72] The image of "ideal beauty" among women and the "muscular body type" image of men has resulted in a lack of body confidence and eating disorders especially when it comes to young teenage girls and boys.

Cigarettes and alcohol advertising[edit]

In advertisements, cigarettes "are used as a fashion accessory and appeal to young women. Other influences on young people include the linking of sporting heroes and smoking through sports sponsorship, the use of cigarettes by popular characters in television programmes and cigarette promotions. Research suggests that young people are aware of the most heavily advertised cigarette brands."[48] Alcohol is portrayed in advertising similarly to smoking, "Alcohol ads continue to appeal to children and portrayals of alcohol use in the entertainment media are extensive".[73] The consumption of alcohol is glamorized and shown without consequences in advertisements, music, magazines, television, film, etc. The advertisements include alcoholic beverages with colorful packaging and sweet tasting flavors, catering to the interests and likes of children and teens. The alcohol industry has a big financial stake in underage drinking, hoping to gain lifelong customers. Therefore, the media are overrun with alcohol ads which appeal to children, involving animal characters, popular music, and comedy.[73]

"Kids are among the most sophisticated observers of ads. They can sing the jingles and identify the logos, and they often have strong feelings about products. What they generally don't understand, however, are the issues that underlie how advertising works. Mass media are used not only to sell goods but also ideas: how we should behave, what rules are important, who we should respect and what we should value."[74]

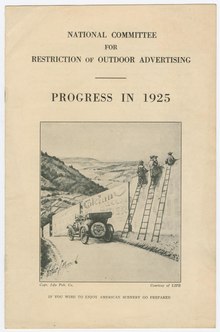

Opposition and campaigns against advertising[edit]

According to critics, the total commercialization of all fields of society, the privatization of public space, the acceleration of consumption and waste of resources including the negative influence on lifestyles and on the environment has not been noticed to the necessary extent. The "hyper-commercialization of the culture is recognized and roundly detested by the citizenry, although the topic scarcely receives a whiff of attention in the media or political culture."[75] "The greatest damage done by advertising is precisely that it incessantly demonstrates the selling out of men and women who lend their intellects, their voices, their artistic skills to purposes in which they themselves do not believe, and ... that it helps to shatter and ultimately destroy our most precious non-material possessions: the confidence in the existence of meaningful purposes of human activity and respect for the integrity of man."[76] "The struggle against advertising is therefore essential if we are to overcome the pervasive alienation from all genuine human needs that currently plays such a corrosive role in our society. But in resisting this type of hyper-commercialism we should not be under any illusions. Advertising may seem at times to be an almost trivial if omnipresent aspect of our economic system. Yet, as economist A. C. Pigou pointed out, it could only be 'removed altogether' if 'conditions of monopolistic competition' inherent to corporate capitalism were removed. To resist it is to resist the inner logic of capitalism itself, of which it is the pure expression."[77]

"Visual pollution, much of it in the form of advertising, is an issue in all the world's large cities. But what is pollution to some is a vibrant part of a city's fabric to others. New York City without Times Square's huge digital billboards or Tokyo without the Ginza's commercial panorama is unthinkable. Piccadilly Circus would be just a London roundabout without its signage. Still, other cities, like Moscow, have reached their limit and have begun to crack down on over-the-top outdoor advertising.[78]

"Many communities have chosen to regulate billboards to protect and enhance their scenic character. The following is by no means a complete list of such communities. Scenic America estimates the nationwide total of cities and communities prohibiting the construction of new billboards to be at least 1500.

A number of states in the US prohibit all billboards:

- Vermont – Removed all billboards in the 1970s

- Hawaii – Removed all billboards in the 1920s

- Maine – Removed all billboards in the 1970s and early '80s

- Alaska – State referendum passed in 1998 prohibits billboards[79]

In 2006, the city of São Paulo, Brazil, ordered the downsizing or removal of all billboards and most other forms of commercial advertising in the city.[80] In 2015, Grenoble, France, similarly banned all billboards and public advertising.[81]

Technical appliances, such as spam filters, remote controls, ad blockers and stickers on mail boxes reading "No Advertising", and an increasing number of court cases indicate a growing interest of people to restrict or rid themselves of unwelcome advertising.

Consumer protection associations, environment protection groups, globalization opponents, consumption critics, sociologists, media critics, scientists and many others deal with the negative aspects of advertising. "Antipub" in France, "subvertising", culture jamming and adbusting have become established terms in the anti-advertising community. On the international level globalization critics such as Naomi Klein and Noam Chomsky are also media and advertising critics. These groups criticize the complete occupation of public spaces, surfaces, the airwaves, the media, schools etc. and the constant exposure of almost all senses to advertising messages, the invasion of privacy, and that only few consumers are aware that they themselves are bearing the costs for this. Some of these groups, such as the Billboard Liberation Front Creative Group in San Francisco or Adbusters in Vancouver, Canada, have manifestos.[82] Grassroots organizations campaign against advertising or certain aspects of it in various forms and strategies and quite often have different roots. Adbusters, for example contests and challenges the intended meanings of advertising by subverting them and creating unintended meanings instead. Other groups, like Illegal Signs Canada, try to stem the flood of billboards by detecting and reporting ones that have been put up without permit.[83] Examples for various groups and organizations in different countries are L'association Résistance à l'Aggression Publicitaire[84] in France, where media critic Jean Baudrillard is a renowned author.[85] The Anti Advertising Agency works with parody and humour to raise awareness about advertising,[86] and Commercial Alert campaigns for the protection of children, family values, community, environmental integrity and democracy.[87]

Media literacy organisations aim at training people, especially children, in the workings of the media and advertising in their programmes. In the US, for example, the Media Education Foundation produces and distributes documentary films and other educational resources.[88] MediaWatch, a Canadian non-profit women's organization, works to educate consumers about how they can register their concerns with advertisers and regulators.[89] The Canadian 'Media Awareness Network/Réseau éducation médias' offers one of the world's most comprehensive collections of media education and Internet literacy resources. Its member organizations represent the public, non-profit but also private sectors. Although it stresses its independence, it accepts financial support from Bell Canada, CTVglobemedia, Canwest, Telus and S-VOX.[90]

Canadian businesses established Concerned Children's Advertisers in 1990 "to instill confidence in all relevant publics by actively demonstrating our commitment, concern, responsibility and respect for children."[91] Members are CanWest, Corus, CTV, General Mills, Hasbro, Hershey's, Kellogg's, Loblaw, Kraft, Mattel, McDonald's, Nestle, Pepsi, Walt Disney, and Weston, as well as almost 50 private broadcast partners and others.[92] Concerned Children's Advertisers was an example for similar organizations in other countries, like 'Media smart' in the United Kingdom, with offspring in Germany, France, the Netherlands and Sweden. New Zealand has a similar business-funded programme called Willie Munchright. "While such interventions are claimed to be designed to encourage children to be critical of commercial messages in general, critics of the marketing industry suggest that the motivation is simply to be seen to address a problem created by the industry itself, that is, the negative social impacts to which marketing activity has contributed. ... By contributing media literacy education resources, the marketing industry is positioning itself as being part of the solution to these problems, thereby seeking to avoid wide restrictions or outright bans on marketing communication, particularly for food products deemed to have little nutritional value directed at children. ... The need to be seen to be taking positive action primarily to avert potential restrictions on advertising is openly acknowledged by some sectors of the industry itself. ... Furthermore, Hobbs (1998) suggests that such programs are also in the interest of media organizations that support the interventions to reduce criticism of the potential negative effects of the media themselves."[69]

There has also been a movement that began in Paris, France, called "POP_DOWN PROJECT" in which they equate street advertising to the annoying pop-up ads on the internet. Their goal is "symbolically restoring everyone's right to non-exposure". They achieve their goal by using stickers of the "Close Window" buttons used to close pop-up ads.[citation needed]

Taxation as revenue and control[edit]

Public interest groups suggest that "access to the mental space targeted by advertisers should be taxed, in that at the present moment that space is being freely taken advantage of by advertisers with no compensation paid to the members of the public who are thus being intruded upon. This kind of tax would be a Pigovian tax in that it would act to reduce what is now increasingly seen as a public nuisance. Efforts to that end are gathering more momentum, with Arkansas and Maine considering bills to implement such a taxation. Florida enacted such a tax in 1987 but was forced to repeal it after six months, as a result of a concerted effort by national commercial interests, which withdrew planned conventions, causing major losses to the tourism industry, and cancelled advertising, causing a loss of 12 million dollars to the broadcast industry alone".[citation needed]

In the US, for example, advertising is tax deductible and suggestions for possible limits to the advertising tax deduction are met with fierce opposition from the business sector, not to mention suggestions for a special taxation. In other countries, advertising at least is taxed in the same manner services are taxed and in some advertising is subject to special taxation although on a very low level. In many cases the taxation refers especially to media with advertising (e.g. Austria, Italy, Greece, Netherlands, Turkey, Estonia). Tax on advertising in European countries:[93]

- Belgium: Advertising or billboard tax (taxe d'affichage or aanplakkingstaks) on public posters depending on size and kind of paper as well as on neon signs

- France: Tax on television commercials (taxe sur la publicité télévisée) based on the cost of the advertising unit

- Italy: Municipal tax on acoustic and visual kinds of advertisements within the municipality (imposta comunale sulla pubblicità) and municipal tax on signs, posters and other kinds of advertisements (diritti sulle pubbliche affisioni), the tariffs of which are under the jurisdiction of the municipalities

- Netherlands: Advertising tax (reclamebelastingen) with varying tariffs on certain advertising measures (excluding ads in newspapers and magazines) which can be levied by municipalities depending on the kind of advertising (billboards, neon signs etc.)

- Austria: Municipal announcement levies on advertising through writing, pictures or lights in public areas or publicly accessible areas with varying tariffs depending on the fee, the surface or the duration of the advertising measure as well as advertising tariffs on paid ads in printed media of usually 10% of the fee.

- Sweden: Advertising tax (reklamskatt) on ads and other kinds of advertising (billboards, film, television, advertising at fairs and exhibitions, flyers) in the range of 4% for ads in newspapers and 11% in all other cases. In the case of flyers the tariffs are based on the production costs, else on the fee

- Spain: Municipalities can tax advertising measures in their territory with a rather unimportant taxes and fees of various kinds.

In his book, When Corporations Rule the World, US author and globalization critic David Korten even advocates a 50% tax on advertising to counterattack what he calls "an active propaganda machinery controlled by the world's largest corporations" which "constantly reassures us that consumerism is the path to happiness, governmental restraint of market excess is the cause of our distress, and economic globalization is both a historical inevitability and a boon to the human species."[94]

Alternative uses of revenue[edit]

Although taxes could raise revenue for governments and councils, recycling the money into other initiatives could have interesting effects: For example, an environmentalist government could set the tax rate on consumption-related advertising to be directly proportional to inflation (1:1). However to maximise effectiveness, the money could be segregated such that it could help indebted advertisers pay down their debts or to subsidise charity and cyclical-economy-based adverts

This example could be part of balancing Countercyclical Fiscal policy with reductions in consumption, in order to reduce the costs of attaining a steady state or degrowth policy.

See also[edit]

- Advertising mail § Criticism

- Subvertising

- Doppelgänger brand image

- Culture jamming

- Killing Us Softly

- Ad blocking

- Attention economy

- Attention theft

- Brandalism

References[edit]

- ^ "Slashdot | ISP Operator Barry Shein Answers Spam Questions". interviews.slashdot.org. 2003-03-03. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "How Marketers Target Kids". Media-awareness.ca. 2009-02-13. Archived from the original on 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Cohen, Andrew C.; Dromi, Shai M. (2018). "Advertising morality: maintaining moral worth in a stigmatized profession". Theory & Society. 47 (2): 175–206. doi:10.1007/s11186-018-9309-7. S2CID 49319915.

- ^ a b Wu, Tim (April 14, 2017). "The Crisis of Attention Theft—Ads That Steal Your Time for Nothing in Return". Wired. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Franck, Georg: Ökonomie der Aufmerksamkeit. Ein Entwurf. (Economy of Attention), 1. Edition. Carl Hanser, March 1998, ISBN 3-446-19348-0, ISBN 978-3-446-19348-2.

- ^ a b c Die Zeit, Hamburg, Germany (2008-11-13). "Öffentlichkeit: Werbekampagnen vereinnahmen den öffentlichen Raum | Kultur | Nachrichten auf ZEIT ONLINE". Die Zeit (in German). Zeit.de. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ad Creep — Commercial Alert". Commercialalert.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 266, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 272, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ a b Lasn, Kalle in: Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America, William Morrow & Company; 1st edition (November 1999), ISBN 0-688-15656-8, ISBN 978-0-688-15656-5

- ^ Kilbourne, Jean: Can't Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel, Touchstone, 2000, ISBN 978-0-684-86600-0

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Lasch, Christopher. The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations, Norton, New York, ISBN 978-0-393-30738-2

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), pp. 132, 249, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), pp. 252, 249, 254, 256, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ a b c d e Lecture held at Philosophicum Lech (Austria) 2002, published in Konrad Paul Liessmann (ed.), Die Kanäle der Macht. Herrschaft und Freiheit im Medienzeitalter, Philosophicum Lech Vol. 6, Vienna: Zsolnay, 2003, pp. 36–60; preprint in Merkur No. 645, January 2003, S. 1–15

- ^ a b Lasch, Christopher: Das Zeitalter des Narzissmus. (The Culture of Narcissism), 1. Edition. Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg 1995.

- ^ "Sut Jhally Website – Advertising at the Edge of the Apocalypse". Sutjhally.com. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Internet Ad Spend To Reach $121B In 2014, 23% Of $537B Total Ad Spend, Ad Tech Boosts Display". April 2014.

- ^ "ZAW – Zentralverband der deutschen Werbewirtschaft e.V". Zaw.de. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Pitch Positive Pledge, The Pledge, accessed 27 December 2022

- ^ Jacobs, K., Make pitching a positive tool, Supply Management, published 16 August 2022, accessed 27 December 2022

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 265, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), pp. 270, 272, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Miller and Rose, 1997, cited in Thrift, 1999, p. 67

- ^ Williams, 1980

- ^ Hudson, R. (2008). "JEG – Sign In Page". Journal of Economic Geography. 8 (3): 421–440. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.620.267. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn005.

- ^ McFall, 2002, p.162

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p.277, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ "Psychology — Commercial Alert". Commercialalert.org. 1999-10-31. Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas"., (May 1, 2008), p. 277, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Siegert, Gabriele, Brecheis Dieter in: Werbung in der Medien- und Informationsgesellschaft, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2005, ISBN 3-531-13893-6

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 256, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ a b Giroux, Henry A., McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, in the foreword for: The Spectacle of Accumulation by Sut Jhally, Sutjhally.com

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 43, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ "Adbusters' Ads Busted". In These Times. 2008-04-04. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ a b "Seminar: Werbewelten – Werbung und Medien" (in German). Viadrina.euv-ffo.de. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p.271, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ a b Jhally, Sut. Advertising at the edge of the apocalypse: Sutjhally.com

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), pp. 269, 270, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ "Selon Le Lay, TF1 a une mission: fournir du "temps de cerveau humain disponible" – [Observatoire français des médias]". Observatoire Medias Australia. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), pp. 235, 237, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Rorty, James: "Our Master's Voice: Advertising" Ayer Co Pub, 1976, ISBN 0-405-08044-1, ISBN 978-0-405-08044-9

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 276, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Jhally, Sut in: Stay Free Nr. 16, 1999

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 213, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ a b Report of the Scientific Committee on Tobacco and Health, Prepared March 20, 1998, in Archive.official-documents.co.uk

- ^ a b Hüther, Jürgen and Stiehler, Hans-Jörg in: Merz, Zeitschrift für Medien und Erziehung, Vol. 2006/6: merzWissenschaft – Sport und Medien, JFF.de Archived 2018-07-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Our Mission". The Anti-Advertising Agency. 2006-01-23. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Eicke, Ulrich in: Die Werbelawine. Angriff auf unser Bewußtsein. München, 1991

- ^ Stay Free Nr. 16, On Advertising, Summer 1999

- ^ Mularz, Stephen. "The Negative Effects of Advertising" (PDF). mularzart.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ Richter, Hans Jürgen. Einführung in das Image-Marketing. Feldtheoretische Forschung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag (Urban TB, 1977). Hieraus: Aufgabe der Werbung S. 12

- ^ "Humanistische Union: Aktuelles". Humanistische-union.de. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ YTV's 2007 Tween Report in: Ontariondp.com

- ^ "How Marketers Target Kids". The Media Awareness Network (MNet). 2010. Archived from the original on 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- ^ Eicke Ulrich u. Wolfram in: Medienkinder: Vom richtigen Umgang mit der Vielfalt, Knesebeck München, 1994, ISBN 3-926901-67-5

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 269, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. "The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas". Monthly Review Press (May 1, 2008), ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Consumer Protection Act, R.S.Q., c. P-40.1, ss. 248-9 (see also: ss. 87–91 of the Consumer Protection Regulations, R.R.Q., 1981, c. P-40.1; and Application Guide for Sections 248 and 249 of the Quebec Consumer Protection Act (Advertising Intended for Children Under 13 Years of Age).

- ^ "Redirection". umontreal.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-02-15. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ Melanie Rother (2008-05-31). "Leichtes Spiel für die Werbeindustrie : Textarchiv : Berliner Zeitung Archiv". Berlinonline.de. Archived from the original on 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Hawkes, Corinna (2004). "Marketing Food to Children: The Global Regulatory Environment" (PDF). World Health Organization. Geneva.

- ^ Cai, Xiaomei (2008). "Advertisements and Privacy: Comparing For-Profit and Non-Profit Web Sites for Children". Communication Research Reports. 25 (1): 67. doi:10.1080/08824090701831826. S2CID 143261392.

- ^ Hsu, Tiffany (2019-09-04). "Popular YouTube Toy Review Channel Accused of Blurring Lines for Ads". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ Perelli, Amanda. "The world's top-earning YouTube star, an 8-year-old boy, has renamed his channel as his business empire grows". Business Insider. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ^ Berg, Madeline. "How This 7-Year-Old Made $22 Million Playing With Toys". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ^ a b "Commercial media literacy: what does it do, to whom-and does it matter? (22-JUN-07)". Journal of Advertising. Accessmylibrary.com. 2007-06-22. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Special Issues for Young Children: Junk food advertising and nutrition concerns". The Media Awareness Network (MNet). 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- ^ Graff, S., Kunkel, D., Mermin E. S. (2012). "Government can regulate food advertising to children because cognitive research shows that it is inherently misleading". Health Affairs. 31 (2): 392–98. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0609. PMID 22323170.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Morris, Anne M; Katzman, Debra K (2003). "The impact of the media on eating disorders in children and adolescents". Paediatrics & Child Health. 8 (5): 287–289. doi:10.1093/pch/8.5.287. ISSN 1205-7088. PMC 2792687. PMID 20020030.

- ^ a b "ERIC ED461810: Teen Tipplers: America's Underage Drinking Epidemic". Education Resources Information Center (United States Department of Education), National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University.

- ^ Schechter, Danny (2009-04-16). "Home". Media Channel. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas. Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 279, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Baran, Paul and Sweezy, Paul (1964) "Monopoly Capital" in: McChesney, Robert W. The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas. Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 52, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ McChesney, Robert W. The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas. Monthly Review Press, New York, (May 1, 2008), p. 281, ISBN 978-1-58367-161-0

- ^ Downie, Andrew (2008-02-08). "São Paulo Sells Itself – Inner Workings of the World's Megacities". Time. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Scenic America: Communities Prohibiting Billboard Construction". Scenic.org. 2008-08-01. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Plummer, Robert (2006-09-19). "Brazil's ad men face billboard ban, BBC News, September 19, 2006". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Mahdawi, Arwa (12 August 2015). "Can cities kick ads? Inside the global movement to ban urban billboards". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Billboard Liberation Front Creative Group". Billboardliberation.com. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Under Construction illegalsigns.ca". illegalsigns.ca.

- ^ "Résistance À l'Agression Publicitaire". Antipub.org. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Media Education Foundation". Mediaed.org. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "The Anti-Advertising Agency". The Anti-Advertising Agency. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Commercial Alert — Protecting communities from commercialism". Commercialalert.org. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Media Education Foundation". Mediaed.org. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Parked domain page". www.mediawatch.ca.

- ^ "MediaSmarts". media-awareness.ca. Archived from the original on 2010-01-06. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ "Mission and Mandate". Cca-kids.ca. Archived from the original on 2009-04-04. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Concerned Children's Advertisers". Cca-kids.ca. Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "DIP21.bundestag.de". bundestag.de. Archived from the original on 2009-06-05. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ Korten, David. (1995) When Corporations Rule the World. 2. Edition 2001: Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, California, ISBN 1-887208-04-6

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Criticism of advertising at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Criticism of advertising at Wikimedia Commons