Death Wish (1974 film)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Death Wish | |

|---|---|

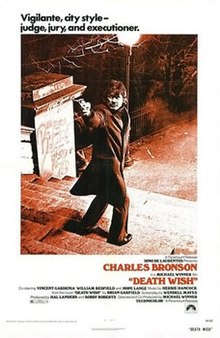

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Winner |

| Screenplay by | Wendell Mayes |

| Based on | Death Wish by Brian Garfield |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Arthur J. Ornitz |

| Edited by | Bernard Gribble |

| Music by | Herbie Hancock |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures (United States) Columbia Pictures (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.7 million[2] |

| Box office | $30 million (US/West Germany) $20.3 million (worldwide rentals)[2] |

Death Wish is a 1974 American vigilante action-thriller film loosely based on the 1972 novel of the same title by Brian Garfield. Directed by Michael Winner, the film stars Charles Bronson as Paul Kersey, an architect who becomes a vigilante after his wife is murdered and daughter molested during a home invasion. It was the first film in the Death Wish film series. It was followed eight years later with Death Wish II and other similar films.

At the time of release, the film was criticized for its apparent support of vigilantism and advocating unlimited punishment of criminals.[3] Allegedly, the novel denounced vigilantism, whereas the film embraced the notion. The film was a commercial success and resonated with the public in the United States, which was experiencing increasing crime rates during the 1970s.[4]

Plot[edit]

Paul Kersey is a middle-aged architect who lives in Manhattan with his wife, Joanna. One day, Joanna and their grown daughter, Carol are followed home by three muggers. The trio invade the Kersey apartment by posing as deliverymen.

Discovering that the women only have $7 on them, the goons beat Joanna and sexually assault Carol before fleeing. At the hospital, Joanna dies from her injuries. After her funeral, Paul has an encounter with a mugger. Paul fights back with a homemade weapon, causing the mugger to run away. Paul is left shaken and energized by the encounter. Paul's boss sends him to Tucson, Arizona, to visit Ames Jainchill, a client with a residential development project. Paul is eventually invited to dinner by Ames at his gun club. Ames is impressed with Paul's pistol marksmanship at the target range.

Paul was a conscientious objector during the Korean War, when he served as a combat medic. He had been taught to handle firearms by his hunter-father, but after the senior Kersey was mortally wounded by a second hunter, who mistook Paul's father for a deer, Paul's mother made him swear never to use guns again. Paul helps Ames plan his residential housing development. Ames drives Paul back to Tucson Airport and places a gift for his work into Paul's checked luggage. In Manhattan, Paul learns that Carol's mind has snapped due to the trauma and Joanna's death. Carol is now catatonic, and an elective mute, with great refusals to speak to her husband Jack especially.

With Paul's blessing, Jack commits Carol to a mental rehabilitation institute. Paul learns that Ames' gift is a revolver and ammunition. He loads the gun, takes a late-night walk and is mugged at gunpoint. Paul fatally shoots the mugger. Shocked, Paul then runs home and vomits. Paul later walks through the city looking for criminals. He kills several muggers over the next weeks, either luring them into a confrontation by presenting himself as an affluent victim, or when he sees them attacking innocent people. NYPD Inspector Frank Ochoa investigates the vigilante killings. His department narrows it down to a list of men who have had a family member recently killed by muggers, and/or are war veterans.

Paul then visits Carol at the institute, where she remains generally depressed and unable to speak or love Jack. She has physically assaulted the psychiatrists out of stress and is being tied to her bed with belts and ropes.

Ochoa soon suspects Paul and is about to make an arrest when the district attorney intervenes and says that "we don't want him." The district attorney and the police commissioner do not want the statistics to get out that Paul's vigilantism has led to a drastic decrease in street crime. They fear that if said information becomes public knowledge, the city will descend into vigilante chaos. If Paul is arrested, he can be labeled a martyr. Ochoa reluctantly relents and opts for "scaring him off" instead. One night, Paul shoots two more muggers before being wounded in the leg by a third. Paul pursues the mugger and corners him at a warehouse. He proposes a fast draw only to faint because of blood loss while the mugger escapes.

A patrolman discovers Paul's gun and hands it to Ochoa, who orders him to forget that he found it. At a hospital, Ochoa visits Paul, who is recovering. Ochoa offers to surreptitiously dispose of the revolver in exchange for Paul's permanent exile from New York. Paul takes the deal, and his company agrees to transfer him to Chicago, while the press is informed that he is an ordinary mugging victim. Paul arrives in Chicago Union Station by train. Being greeted by a company representative, he notices hoodlums harassing a young woman. He excuses himself and helps her. As the hoodlums mock him, Paul smiles while making a finger gun at them.

Cast[edit]

- Charles Bronson as Paul Kersey

- Hope Lange as Joanna Kersey

- Vincent Gardenia as Inspector Frank Ochoa

- William Redfield as Sam Kreutzer

- Chris Gampel as Henry Ives

- Steven Keats as Jack Toby

- Stuart Margolin as Ames Jainchill

- Stephen Elliott as Police Commissioner Dryer

- Fred J. Scollay as District Attorney Peters

- Kathleen Tolan as Carol Kersey-Toby

- Jack Wallace as Detective Hank

- Robert Kya-Hill as Officer Joe Charles

- Jeff Goldblum as Freak #1

- Christopher Logan as Freak #2

- Gregory Rozakis as Freak #3 (with spraypaint-can)

- Christopher Guest as Officer Jackson Reilly

- Hank Garrett as Andrew McCabe

- Helen Martin as Alma Lee Brown

- Olympia Dukakis as Officer Gemetti

- Marcia Jean Kurtz as Receptionist

- Edward Grover as Lieutenant Briggs

- John Herzfeld as Train Mugger

- Eric Laneuville as Train Station Mugger

- Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs as Park Mugger

- Sonia Manzano as Grocery Clerk

- Tom Hayden as E.R. Doctor

- Al Lewis as Security Guard in Lobby

- Billy Curtis as Newspaper Hawker

- Paul Dooley as Cop At Hospital (uncredited)

- Art Evans as Cop At Precinct (uncredited)

- Robert Miano as Mugger (uncredited)

- William Bogert as Fred Brown (uncredited)

John Herzfeld played the greaser who slashes Paul Kersey's newspaper, while Robert Miano had a minor role as a mugger in the film. Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs, who later co-starred on the television show Welcome Back, Kotter, had an uncredited role as one of the Central Park muggers near the end of the film. It has been rumored that Denzel Washington made his screen debut as an uncredited alley mugger since in a long shot, the actor shown appears to resemble him, but Washington stated that not to be true.[5]

Actress Helen Martin, who had a minor role as a mugging victim who fights off her attackers with a hatpin, subsequently appeared in the television sitcoms Good Times and 227. Christopher Guest made one of his earliest film appearances as a young police officer who finds Kersey's gun. Marcia Jean Kurtz, who played the receptionist at Paul's office, has appeared in multiple roles on the TV series Law & Order. Sonia Manzano, who played Maria on Sesame Street, had an uncredited role as a supermarket checkout clerk.

The film marked Jeff Goldblum's screen debut, playing one of the "freaks" who assaults Kersey's family early in the film. The producers of Death Wish were Hal Landers & Bobby Roberts. Bobby Roberts was also the manager of the rock group, Steppenwolf, at that time. Apparently, Jeff Goldblum struck up a friendship with Steppenwolf keyboardist, Goldy McJohn, because Goldy once said, Jeff Goldblum was his cigarette-mooching pal.

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

The film was based on Brian Garfield's 1972 novel of the same name. Garfield was inspired to use the theme of vigilantism following incidents in his personal life. In one incident, his wife's purse was stolen; in another, his car was vandalized. His initial thought each time was that he could kill "the son of a bitch" responsible. He later considered that these were primitive thoughts, contemplated in an unguarded moment. He then thought of writing a novel about a man who entered that way of thinking in a moment of rage and then never emerged from it.[6]

The original novel received favorable reviews but was not a bestseller. Garfield sold screen rights to both Death Wish and Relentless to the only film producers who approached him, Hal Landers and Bobby Roberts. He was offered the chance to write a screenplay adapting one of the two novels, and chose Relentless. He simply considered it the easier of the two to turn into a film.[6] Wendell Mayes was then hired to write the screenplay for Death Wish. He preserved the basic structure of the novel and much of the philosophical dialogue. It was his idea to turn police detective Frank Ochoa into a major character of the film.[6]

His early drafts for the screenplay had different endings from the final one. In one, he followed an idea from Garfield. The vigilante confronts the three thugs who attacked his family and ends up dead at their hands. Ochoa discovers the dead man's weapon and considers following in his footsteps.[6] In another, the vigilante is wounded and rushed to a hospital. His fate is left ambiguous. Meanwhile, Ochoa has found the weapon and struggles with the decision to use it. His decision is left unclear.[6]

Casting[edit]

Originally, Sidney Lumet was to have directed Jack Lemmon as Paul and Henry Fonda as Ochoa.[7] Lumet bowed out of the project to direct Serpico (1973), requiring a search for another director.[6] Several were considered, including Peter Medak who wanted Henry Fonda as Paul.[8] United Artists eventually chose Michael Winner, due to his track record of gritty, violent action films. The examples of his work considered included The Mechanic (1972), Scorpio (1973), and The Stone Killer (1973).[6]

The film was rejected by other studios because of its controversial subject matter and the perceived difficulty of casting someone in the vigilante role. Several actors were considered, including Steve McQueen, Clint Eastwood, Burt Lancaster, George C. Scott, Frank Sinatra, Lee Marvin and even Elvis Presley. Winner attempted to recruit Bronson, but there were two problems for the actor. One was that his agent, Paul Kohner, considered that the film carried a dangerous message. The other was that the screenplay followed the original novel in describing the vigilante as a meek accountant, hardly a suitable role for Bronson.[6] "I was really a miscast person," Bronson said later. "It was more a theme that would have been better for Dustin Hoffman or somebody who could play a weaker kind of man. I told them that at the time."[9]

Winner was anxious about his decision to cast Jill Ireland, Bronson's real life wife for the role of Paul Kersey's wife, Joanna Kersey. After Winner told this to Bronson, he said, "No. I don't want her humiliated and messed around by these actors who play muggers. You know the sort of person we want? Someone who looks like Hope Lange.", to which Winner replied, "Well, Charlie, the person who looks most like Hope Lange is Hope Lange. So I'll get her.". Ireland later played Kersey's love interest in, Death Wish II. The film project was dropped by United Artists after budget constraints forced producers Hal Landers and Bobby Roberts to liquidate their rights. The original producers were replaced by Italian film mogul Dino De Laurentiis.[7]

De Laurentiis convinced Charles Bluhdorn to bring the project to Paramount Pictures. Paramount purchased the distribution rights of the film in the United States market, while Columbia Pictures licensed the distribution rights for international markets. De Laurentiis raised the $3 million budget of the film by pre-selling the distribution rights.[7]

With funding secured, screenwriter Gerald Wilson was hired to revise the script. His first task was changing the identity of the vigilante to make the role more suitable for Bronson. "Paul Benjamin" was renamed to "Paul Kersey." His job was changed from accountant to architect. His background changed from a World War II veteran to a Korean War veteran. The reason for him not seeing combat duty changed from serving as an army accountant to being a conscientious objector.[6] Several vignettes from Mayes' script were deemed unnecessary and so were deleted.[6]

Filming[edit]

Winner asked for several revisions in the script. Both the novel and the original script had no scenes showing the vigilante interacting with his wife. Winner decided to include a prologue depicting a happy relationship and so the prologue of the film depicts the couple vacationing in Hawaii.[6] The early draft of the script had the vigilante being inspired by seeing a fight scene in the Western film High Noon. Winner decided on a more elaborate scene, involving a fight scene in a recreation of the Wild West, taking place in Tucson, Arizona.[6]

The final script had the vigilante making an occasional reference to Westerns. While confronting an armed mugger, he challenges him to draw. Kersey tells him to "fill your hand," the same challenge issued by Western movie icon John Wayne to his main opponent in the climactic shootout in 1969's True Grit. When Ochoa tells him to get out of town, he asks if he has until sundown to do so.[6] The killing in the subway station was supposed to remain off-screen in Mayes' script, but Winner decided to turn this into an actual, brutal scene.[6] A minor argument occurred when it came to a shooting location for the film. Bronson asked for a California-based location so that he could visit his family in Bel Air, Los Angeles. Winner insisted on New York City and De Laurentiis agreed. Ultimately, Bronson backed down.[6]

Death Wish was shot on location in New York City from January 14, 1974 to Mid-April 1974.[6] Death Wish was first released to American audiences in July 1974. The world premiere took place on July 24 in the Loews Theater in New York City.[6] During the whole production, the crew members had to wear face masks, due to the freezing temperatures that made the water in their eyes freeze.

Music[edit]

Multiple Grammy award-winning jazz musician Herbie Hancock produced and composed the original score for the soundtrack to the movie. It was his third film score, after the 1966 movie Blow-up and The Spook Who Sat By The Door (1973). Michael Winner said, "[Dino] De Laurentiis said 'Get a cheap English band.' Because the English bands were very successful. But I had a girlfriend who was in Sesame Street, a Puerto Rican actress (Sonia Manzano), who played a checkout girl at the supermarket [in Death Wish], and she was a great jazz fan. She said, 'Well, you should have Herbie Hancock. He's got this record out called Head Hunters.' She gave me Head Hunters, which was staggering. And I said, 'Dino, never mind a cheap English band, we'll have Herbie Hancock.' Which we did."[citation needed]

Hancock's theme for the film was quoted in "Judge, Jury and Executioner," a 2013 single by Atoms for Peace.[citation needed]

Release[edit]

Home media[edit]

The film was first released on VHS, Betamax and LaserDisc in 1980. It was later released on DVD in 2001 and 2006. A 40th Anniversary Edition was released on Blu-ray in 2014.[10]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Death Wish received mixed reviews from critics upon its release.[11][12]

Many critics were displeased with the film, considering it an "immoral threat to society" and an encouragement of antisocial behavior. Vincent Canby of The New York Times was one of the most outspoken writers, condemning Death Wish in two extensive articles.[13][14][15] Roger Ebert awarded three stars out of four and praised the "cool precision" of Winner's direction but did not agree with the film's philosophy.[16] Gene Siskel gave the film two stars out of four and wrote that its setup "makes no attempt at credibility; its goal is to present a syllogism that argues for vengeance, and to present it so swiftly that one doesn't have time to consider its absurdity."[17]

Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "a despicable motion picture... It is nasty and demagogic stuff, an appeal to brute emotions and against reason."[18] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post described the film as "simplistic to the point of stasis. Scarcely a single sensible insight into urban violence occurs; the killings just plod [along] one after another as Bronson stalks New York's crime-ridden streets."[19] Clyde Jeavons of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "Superficially, it's not all that far removed from a Budd Boetticher revenge Western ... The difference, of course, is that Michael Winner has none of Boetticher's indigenous sense of allegory or his instinct for what constitutes a good folk-mythology, let alone his relish for three-dimensional villains."[20]

Garfield was also unhappy with the final product, calling the film "incendiary" and stated that the film's sequels are all pointless and rancid since they advocate vigilantism unlike his two novels, which make the opposite argument. The film led him to write a follow-up titled Death Sentence, which was published a year after the film's release. Bronson defended the film and felt that it was intended to be a commentary on violence and was meant to attack violence, not romanticize it.

On Rotten Tomatoes Death Wish has an approval rating of 66% "Fresh" based on reviews from 32 critics.[3]

Box office[edit]

The film grossed $22 million in the United States and Canada generating theatrical rentals of $8.8 million.[21][22] In West Germany it grossed over $7.6 million.[23] It earned theatrical rentals of $20.3 million worldwide.[2]

Year-end lists[edit]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – Nominated[24]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Paul Kersey – Nominated Hero[25]

Impact and influence[edit]

Death Wish was a watershed for Bronson, who was 52 years of age at the time, and who was then better known in Europe and Asia for his role in The Great Escape. Bronson became an American film icon, who experienced great popularity over the next twenty years.

- In the series' later years, the Death Wish franchise became a subject of parody for its high level of violence and the advancing age of Bronson (a 1995 episode of The Simpsons, "A Star Is Burns," showed a fictional advertisement for Death Wish 9, consisting of a bed-ridden Bronson saying "I wish I was dead"). However, the Death Wish franchise remained lucrative and drew support from fans of exploitation cinema. The series continues to have a widespread following on home video and is occasionally broadcast on various television stations in the US and Europe.

- In 2019, during the seventy-fourth session of the United Nations General Assembly, Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan referred to Death Wish while explaining the possibility of radicalization of Kashmiri youth as a result of the Indian revocation of Jammu and Kashmir's special status, part of the Kashmir conflict.[26]

Remake[edit]

In March 2016, Paramount and MGM announced that Aharon Keshales and Navot Papushado would direct a remake starring Bruce Willis.[27] In May, Keshales and Papushado quit the project, after the studio failed to allow their script rewrites. In June, Eli Roth signed on to direct. The film was released on March 2, 2018.[28][29]

See also[edit]

- Death Wish film series

- List of American films of 1974

- List of hood films

- List of films featuring home invasions

- Il giustiziere di mezzogiorno, a Death Wish parody film

References[edit]

- ^ "DEATH WISH (X)". British Board of Film Classification. October 23, 1974. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Knoedelseder, William K. Jr. (August 30, 1987). "De Laurentiis Producer's Picture Darkens". Los Angeles Times. p. 1 Part IV.

- ^ a b "Death Wish Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 13. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ^ Shager, Nick (December 22, 2016). "Denzel Washington Shoots Down Rumor He's in 1974 'Death Wish': 'I Wasn't Even an Actor Yet'". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Talbot (2006), p. 1-31

- ^ a b c Nikki Tranter. "Historian: Interview with Brian Garfield".

- ^ p. 23 Ross, Cai Ghost Buster in Cinema Retro Vol 15 Issue #43 Winter 2019

- ^ For Bronson, Piecework Is a Virtue: Movies Piecework a Virtue for Charles Bronson Piecework a Virtue for Bronson Warga, Wayne. Los Angeles Times 2 Nov 1975: o1

- ^ Webmaster (October 23, 2013). "Death Wish: 40th Anniversary Edition Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ^ "Death Wish". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ "Review: 'Death Wish'". Variety. December 31, 1973. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (August 4, 1974). "Screen: 'Death Wish' Exploits Fear Irresponsibly; 'Death Wish' Exploits Our Fear". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (July 25, 1974). "Screen: 'Death Wish' Hunts Muggers:The Cast Story of Gunman Takes Dim View of City". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ Severo, Richard (September 1, 2003). "Charles Bronson, 81, Movie Tough Guy, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Death Wish, Roger Ebert's Movie Reviews Archived October 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (August 9, 1974). "'Death' moves at a killing pace to prove its point". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 3.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (July 31, 1974). "Running Amok for Law, Order". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (August 22, 1974). "'Death Wish': Vigilante Justice". The Washington Post. B13.

- ^ Jeavons, Clyde (January 1975). "Death Wish". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 42 (492): 7.

- ^ "Death Wish, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ "Death Wish, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ Kocian, Billy (May 7, 1975). "In Germany Big Pics Do Biz". Variety. p. 275. Retrieved April 13, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ 🇵🇰 Pakistan - Prime Minister Addresses General Debate, 74th Session, 28 September 2019.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (March 4, 2016). "'Death Wish' Revamp With Bruce Willis To Be Helmed By 'Big Bad Wolves' Directors Aharon Keshales & Navot Papushado". Deadline Hollywood.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (June 20, 2016). "Eli Roth To Direct Bruce Willis In 'Death Wish' Remake". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ McNary, Dave (June 8, 2017). "Bruce Willis' 'Death Wish' remake lands November launch with Annapurna". Variety. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

External links[edit]

- Death Wish at IMDb

- Death Wish at the TCM Movie Database

- Death Wish at Box Office Mojo

- Death Wish at Rotten Tomatoes