Dynasty of Isin

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Dynasty of Isin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1953 BCE – c. 1717 BCE | |||||||||

Location of Isin, now in modern Iraq | |||||||||

| Capital | Isin | ||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian, Sumerian | ||||||||

| Religion | Sumerian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King of Sumer | |||||||||

• c. 1953—1921 BCE | Ishbi-Erra (first) | ||||||||

• c. 1740—1717 BCE | Damiq-ilishu (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Established | c. 1953 BCE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 1717 BCE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq | ||||||||

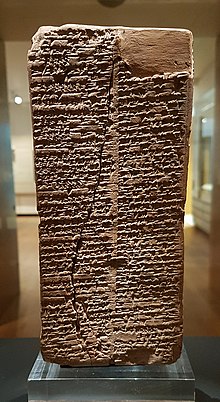

The Dynasty of Isin refers to the final ruling dynasty listed on the Sumerian King List (SKL).[1] The list of the Kings Isin with the length of their reigns, also appears on a cuneiform document listing the kings of Ur and Isin, the List of Reigns of Kings of Ur and Isin (MS 1686).[2]

The dynasty was situated within the ancient city of Isin (today known as the archaeological site of Ishan al-Bahriyat). It is believed to have flourished c. 1953–1717 BCE according to the short chronology timeline of the ancient Near East. It was preceded on the Sumerian King List by the Third Dynasty of Ur. The Dynasty of Isin is often associated with the nearby and contemporary dynasty of Larsa (1961–1674 BCE), and they are often regrouped for periodization purposes under the name "Isin-Larsa period". Both dynasties were succeeded by the First Babylonian Empire.

History[edit]

Reign of Ishbi-Erra[edit]

Ishbi-Erra (fl. c. 1953—1920 BCE by the short chronology) was the founder of the Dynasty of Isin. Ishbi-Erra of the First Dynasty of Isin was preceded by Ibbi-Sin of the Third Dynasty of Ur in ancient Lower Mesopotamia, and then succeeded by Šu-ilišu. According to the Weld-Blundell Prism,[i 1] Ishbi-Erra reigned for 33 years and this is corroborated by the number of his extant year-names. While in many ways this dynasty emulated that of the preceding one, its language was Akkadian as the Sumerian language had become moribund in the latter stages of the Third Dynasty of Ur.

At the outset of his career, Ishbi-Erra was an official working for Ibbi-Sin, the last king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Ishbi-Erra was described as a man of Mari,[i 2] either his origin or the city for which he was assigned. His progress was witnessed in correspondence with the king and between Ibbi-Sin and the governor of Kazallu (Puzur-Numushda, latterly renamed Puzur-Šulgi.) These are literary letters, copied in antiquity as scribal exercises and whose authenticity is unknown.[3] Charged with acquiring grain in Isin and Kazallu, Ishbi-Erra complained that he could not ship the 72,000 GUR he had bought for 20 talents of silver—apparently an exorbitant price—and now kept secure in Isin to other conurbations due to the incursions of the Amorites (“Martu”) and requested Ibbi-Sin supply 600 boats to transport it while also requesting governorship of Isin and Nippur.[i 3][4] Although Ibbi-Sin baulked at promoting him, Ishbi-Erra had apparently succeeded in wrestling control over Isin by Ibbi-Sin's 8th year, when he began assigning his own regnal year-names, and thereafter an uneasy chill descended on their relationship.[5]

Ibbi-Sin bitterly lambasted Ishbi-Erra as “not of Sumerian seed” in his letter to Puzur-Šulgi and opined that: “Enlil has stirred up the Amorites out of their land, and they will strike the Elamites and capture Ishbi-Erra.” Curiously, Puzur-Šulgi seems to have originally been one of Ishbi-Erra's own messengers and indicates the extent to which loyalties were in flux during the waning years of the Ur III regime. While there was no outright conflict, Ishbi-Erra continued to extend his influence as Ibbi-Sin's steadily declined over the next 12 years or so, until Ur was finally conquered by Kindattu of Elam.[6]

Ishbi-Erra went on to win decisive victories against: the Amorites in his 8th year and the Elamites in his 16th years. Some years later, Ishbi-Erra ousted the Elamite garrison from Ur, thereby asserting suzerainty over Sumer and Akkad, celebrated in one of his later 27th year-name, although this specific epithet was not used by this dynasty until the reign of Iddin-Dagan.[3] He readily adopted the regal privileges of the former regime, commissioning royal praise poetry and hymns to deities, of which seven are extant, and proclaiming himself Dingir-kalam-ma-na, “a god in his own country.”[i 4] He appointed his daughter, En-bara-zi, to succeed that of Ibbi-Sin's as Egisitu-priestess of An, celebrated in his 22nd year-name. He founded fortresses and installed city walls, but only one royal inscription is extant.[i 5][7]

Reign of Shu-Ilishu[edit]

Shu-Ilishu (fl. c. 1920—1900 BCE by the short chronology) was the 2nd ruler of the Dynasty of Isin. He reigned for 10 years (according to his extant year-names and a single copy of the SKL,[i 6] which differs from the 20 years recorded by others.)[i 7][8] Šu-ilišu was preceded by Išbi-erra. Iddin-Dagān then succeeded Šu-ilišu. Šu-ilišu is best known for his retrieval of the cultic idol of Nanna from the Elamites and its return to the city-state Ur.

Šu-ilišu's inscriptions gave him the titles: “Mighty Man” — “King of Ur” — “God of His Nation” — “Beloved of the gods: Anu, Enlil, and Nanna” — “King of the Land of Sumer and Akkad” — “Beloved of the god Enlil and the goddess Ninisina” — “Lord of his Land”, but not “King of Isin” (a title which was not claimed by a ruler of this city-state until the later reign of Išme-Dagān.) Šu-ilišu did, however; rebuild the walls of his capital city: Isin. He was a great benefactor of the city-state Ur (beginning the restoration which was to continue through his successors: Iddin-Dagān and Išme-Dagan.) Šu-ilišu built a monumental gateway and recovered an idol representing Ur's patron deity (Nanna, god of the moon) which had been expropriated by the Elamites when they sacked the city-state, but; whether he obtained it either through diplomacy or conflict is unknown.[9] An inscription tells of the city-state's resettlement: “He established for him when he established in Ur the people scattered as far as Anšan in their abode.”[10] The "Lamentation over the Destruction of Ur" was composed around this time to explain the catastrophe, to call for its reconstruction and to protect the restorers from the curses attached to the ruins of the é.dub.lá.maḫ.

Šu-ilišu commemorated: the fashioning of a great emblem for Nanna, an exalted throne for An, a dais for Ninisin, a magur-boat for Ninurta, and a dais for Ningal in year names for Šu-ilišu's reign. An adab (or hymn) to Nergal[i 8] was composed in honor of Šu-ilišu, together with an adab of An and perhaps a 3rd addressed to himself.[11] The archive of a craft workshop (or giš-kin-ti) from the city-state Isin has been uncovered with 920 texts dating from Išbi-Erra year 4 through to Šu-ilišu year 3 — a period of 33 years. The tablets are records of receipts and disbursements of the: leather goods, furniture, baskets, mats, and felt goods that were manufactured along with their raw materials.[12] A 2nd archive (of receipt of cereal and issue of bread from a bakery, possibly connected to the temple of Enlil in Nippur) includes an accounting record[i 9] of expenditures of bread for the provision of the king and includes entries dated to his 2nd through 9th years[13] which was used by Steele to determine the sequence of most of this king's year-names.[10]

Reign of Iddin-Dagan[edit]

Iddin-Dagan (fl. c. 1900—1879 BCE by the short chronology) was the 3rd king of the Dynasty of Isin. Iddin-Dagān was preceded by his father Šu-ilišu. Išme-Dagān (to be confused with neither Išme-Dagān I nor Išme-Dagān II of the Old Assyrian Empire) then succeeded Iddin-Dagān. Iddin-Dagān reigned for 21 years (according to the SKL.)[i 11] He is best known for his participation in the sacred marriage rite and the risqué hymn that described it.[14]

His titles included: "Mighty King", "King of Isin", "King of Ur", "King of the Land of Sumer and Akkad".[nb 1] The 1st year name recorded on a receipt for flour and dates[i 12] reads: “Year Iddin-Dagān (was) king and (his) daughter Matum-Niatum (“the land which belongs to us”) was taken in marriage by the king of Anshan.”[nb 2][15] Vallat suggests it was to Imazu (son of Kindattu, who was the groom and possibly the king of the region of Shimashki)[i 13] as he was described as the King of Anshan in a seal inscription, although elsewhere unattested. Kindattu had been driven away from the city-state of Ur by Išbi-Erra[i 14] (the founder of the First Dynasty of Isin), however; relations had apparently thawed sufficiently for Tan-Ruhurarter (the 8th king to wed the daughter of Bilalama, the énsí of Eshnunna.)[16]

There is only 1 contemporary monumental text extant for this king and another 2 known from later copies. A fragment of a stone statue[i 15] has a votive inscription which invokes Ninisina and Damu to curse those who foster evil intent against it. 2 later clay tablet copies[i 16] of an inscription recording an unspecified object fashioned for the god Nanna were found by the British archaeologist Sir Charles Leonard Woolley in a scribal school house in the city-state of Ur. A tablet[i 17] from the Enunmaḫ at the city-state of Ur dated to the 14th year of Gungunum (fl. c. 1868 BCE — c. 1841 BCE) of Larsa, after his conquest of the city, bears the seal impression of a servant of his. A tablet[i 18] described Iddin-Dagān's fashioning of two copper festival statues for Ninlil, which were not delivered to Nippur until 170 years later by Enlil-bāni.[17] Belles-lettres preserve the correspondence from Iddin-Dagān to his general Sîn-illat about Kakkulātum and the state of his troops, and from his general describing an ambush by the Martu (Amorites).

The continued fecundity of the land was ensured by the annual performance of the sacred marriage ritual in which the king impersonated Dumuzi-Ama-ušumgal-ana and a priestess substituted for the part of Inanna. According to the šir-namursaḡa, the hymn composed describing it in 10 sections (Kiruḡu), this ceremony seems to have entailed the procession of: male prostitutes, wise women, drummers, priestesses and priests bloodletting with swords, to the accompaniment of music, followed by offerings and sacrifices for the goddess Inanna, or Ninegala.

Reign of Ishme-Dagan[edit]

Ishme-Dagan (fl. c. 1879—1859 BCE by the short chronology) was the 4th king of the Dynasty of Isin, according to the SKL. Also according to the SKL: he was both the son and successor of Iddin-Dagān. Lipit-Ištar then succeeded Išme-Dagān. Išme-Dagān was one of the kings to restore the Ekur.

Reign of Lipit-Ishtar[edit]

Lipit-Ishtar (fl. c. 1859—1848 BCE by the short chronology) was the 5th king of the Dynasty of Isin, according to the SKL. Also according to the SKL: he was the successor of Išme-Dagān. Ur-Ninurta then succeeded Lipit-Ištar. Some documents and royal inscriptions from his time have survived, however; Lipit-Ištar is mostly known due to the Sumerian language hymns that were written in his honor, as well as a legal code written in his name (preceding the famed Code of Hammurabi by about 100 years)—which were used for school instruction for hundreds of years after Lipit-Ištar's death. The annals of Lipit-Ištar's reign recorded that he also repulsed the Amorites.

Reign of Ur-Ninurta[edit]

Ur-Ninurta (fl. c. 1848—1820 BCE by the short chronology) was the 6th king of the Dynasty of Isin. A usurper, Ur-Ninurta seized the throne on the fall of Lipit-Ištar and held it until his violent death some 28 years later.

He called himself “son of Iškur,” the southern storm-god synonymous with Adad, in his adab to Iškur.[i 19] His name was wholly Sumerian, in marked contrast to the Amorite names of his five predecessors. There are only two extant inscriptions, one of which is stamped on bricks in 13 lines of Sumerian from the cities of Nippur, Isin, Uruk and Išān Ḥāfudh, a small site southeast of Tell Drehem, which gives his standard inscription[i 20] describing him as an “Išippum priest with clean hands for Eridu, favorite en priest of Uruk” and there is a copy of an inscription relating to the erection of a statue of the king with a votive goat.[i 21][18]

He was contemporary with Gungunum, c. 1868 – 1841 BCE (short), and his successor Abī-sarē, c. 1841 – 1830 BCE (short), the resurgent kings of Larsa. His reign marks the beginning of a decline in Isin's fortunes coinciding with a rise in those of Larsa. Gungunum had wrestled Ur from Isin's control by his 10th year and it is possible this was the cause of Lipit-Ištar's overthrow. Indeed, Ur-Ninurta made a dedicatory gift to the temple of Ningal in Ur during the 9th year of Gungunum. However, Ur-Ninurta continued to mention Ur in his titles ("herdsman of Ur") as did his successors in Isin. Gungunum went on to expand his kingdom, perhaps taking Nippur late in his reign. His death allowed Ur-Ninurta to launch a temporary counter-offensive, recapturing Nippur and several other cities on the Kishkattum canal. His year-name “year (Ur-Ninurta) set for Enlil free (of forced labor) for ever the citizens of Nippur and released (the arrears of) the taxes which they were bearing on their necks” may mark this point. His offensive was stopped at Adab, modern Bismaya, where Abī-sarē “defeated the army of Isin with his weapon,” in the 9th year-name of his reign.[19] It may be that this battle was where he was killed, as a year A of Halium of the kingdom of Mananâ,[nb 3] reads “the year Ur-Ninurta was slain” and Manabalte’el of Kisurra’s year G,[nb 4] “the year Ur-Ninurta was killed.”[20]

There is a year name[nb 5] “year following the year that king Ur-Ninurta made emerge large a.gàrs from the water.” Marten Stol suggests that it indicates he succeeded in converting swamp or similar into cultivatable land.[21]

A curious legal case arose came to his attention which he ordered by heard by the Assembly of Nippur. Lu-Inanna, a nišakku priest was murdered by Nanna-sig, Ku-Enlilla (a barber) and Enlil-ennam (an orchard-keeper) who then confessed to his estranged wife, Nin-dada, who remained suspiciously silent on the matter. Nine persons, with occupations ranging from bird-catcher to potter, presented the prosecution's case. Two others sprang to the defense of the widow, as she had not actually participated in the murder, but the assembly concluded she must have been “involved” with one of the murders and consequently in cahoots with them. All four were condemned to execution in front of the victim's chair.[22]

The Instructions of Ur-Ninurta and Counsels of Wisdom is a Sumerian courtly composition which extols the virtues of the king, the reestablisher of order, justice and cultic practices after the flood in emulation of the older role models Gilgamesh and Ziusudra.[23] The SKL[i 22] gives his reign for 28 years. He was succeeded by his son, Būr-Sīn.

Reign of Bur-Suen[edit]

Bur-Suen (fl. c. 1820—1799 BCE by the short chronology) was the 7th king of the Dynasty of Isin and ruled for 21 years according to the SKL,[i 23] 22 years according to the Ur-Isin king list.[i 24][24] His reign was characterized by an ebb and flow in hegemony over the religious centers of Nippur and Ur.

The titles “shepherd who makes Nippur content,” "mighty farmer of Ur," “who restores the designs for Eridu” and “en priest for the mes, for Uruk” were used by Bur-Suen in his standard brick inscriptions in Nippur and Isin,[i 25] although it seems unlikely that his rule stretched to Ur or Eridu at this time as the only inscriptions with an archaeological provenance come from the two northerly cities.[25] A solitary tablet from Ur is dated to his first year, but this is thought to correspond to Abē-sarē's year 11, for which several tablets attest to his reign over Ur.

He was contemporary with the tail end of the reign of Abī-sarē, ca, 1841 to 1830 BCE (short) and that of Sūmú-El, c. 1830 to 1801 BCE (short), the kings of Larsa. This latter king's year-names record victories over Akusum, Kazallu, Uruk (which had seceded from Isin), Lugal-Sîn, Ka-ida, Sabum, Kiš, and village of Nanna-isa, relentlessly edging north and feverish activity digging canals or filling them in, possibly to counter the measures taken by Bur-Suen to contain him.[26] Only nine of Bur-Suen's own year-names are known and the sequence is uncertain. He seized control of Kisurra for a time as two year-names are found among tablets from this city, possibly following the departure of Sumu-abum the king of Babylon who “returned to his city.” The occupation was brief, however, as Sumu-El was to conquer it during his fourth year.[27] Other year-names record Bur-Suen's construction of fortifications, walls on the bank of the Eurphrates and a canal. A year-name of Sumu-El records “Year after the year Sumu-El has opened the palace (?) of Nippur,” whose place in this king's sequence is unknown.[27]

A red-brown agate statuette was dedicated to goddess Inanna[i 26] and an agate plate[i 27] was dedicated by the lukur priestess and his “traveling companion,” i.e. concubine, Nanāia Ibsa. A certain individual by the name of Enlil-ennam dedicated a dog figurine to the goddess Ninisina for the life of the king. There are around five extant seals and seal impressions of his servants and scribes,[28] three of which were excavated in Ur suggesting a fleeting late reoccupancy of this city at the end of his reign and the beginning of his successor's as coincidentally no texts from Ur bear Sumu-El's years 19 to 22 which correspond with this period.[26]

Reign of Lipit-Enlil[edit]

Lipit-Enlil, written dli-pí-it den.líl, where the SKL[i 28] and the Ur-Isin king list [i 29] match on his name and reign, was the 8th king of the 1st dynasty of Isin and ruled for five years, ca. 1810 BCE – 1806 BCE (short chronology) or 1873–1869 BCE (middle chronology). He was the son of Būr-Sîn.[29]

There are no inscriptions known for this king.[30] His brief reign ended a period of relative stability and he was succeeded by Erra-Imittī whose filiation is unknown, as the SKL omits this information from this point on. Both he and his successor were conspicuous in the absence of royal hymns or dedicatory prayers and Hallo speculates this may have been due to the distractions afforded by the commencement of conflict with Larsa.[31]

The archives of the temple of Ninurta, the é-šu-me-ša4, in Nippur, extended over more than seventy-five years, from year 1 of Lipit-Enlil of Isin (1810) to year 28 of Rim-Sin I (1730) and were inadvertently preserved when they were used as infill for the temple of Inanna in the Parthian period. The 420 fragments show a thriving temple economy absorbing much of the available wealth.[32] The year-names following his accession year all somewhat monotonously commemorate generous gifts to the temple of Enlil.

Reign of Erra-imitti[edit]

Erra-imitti (fl. c. 1794—1786 BCE) was king of Isin, modern Ishan al-Bahriyat, and according to the SKL ruled for eight years. He succeeded Lipit-Enlil, with whom his relationship is uncertain and was a contemporary and rival of Sūmû-El and Nūr-Adad of the parallel dynasty of Larsa. He is best known for the legendary tale of his demise, Shaffer's “gastronomic mishap”.[33]

He seems to have recovered control of Nippur from Larsa early in his reign but perhaps lost it again, as its recovery is celebrated again by his successor. The later regnal year-names offer some glimmer of events, for example “the year following the year Erra-imitti seized Kisurra"[nb 6] (the modern site of Abū-Ḥaṭab) for the date of a receipt for a bridal gift and “the year Erra-imitti destroyed the city wall of Kazallu,”[nb 7][34] a city allied with Larsa and antagonistic to Isin and its ally, Babylon. His conquest of Kisurra would have been a significant escalation of hostilities against Isin's rival Larsa.[35] A haematite cylinder seal[i 30] of his servant and scribe Iliška-uṭul, son of Sîn-ennam, has come to light from this city, suggesting prolonged occupation.[36] The latest attested year-name gives the year he built the city wall of gan-x-Erra-Imittī, perhaps an eponymous new town.

When the omens predicted impending doom for a monarch, it was customary to appoint a substitute as a "statue though animate",[nb 8] a scape-goat who stood in the place of the king but did not exercise power for a hundred days to deflect the disaster, at the end of which the proxy and his spouse would be ritually slaughtered and the king would resume his throne.[37]

Reign of Enlil-bani[edit]

Enlil-bani (fl. c. 1786—1762 BCE by the short chronology) was the 10th king of the Dynasty of Isin and reigned 24 years according to the Ur-Isin kinglist.[i 31] He is best known for the legendary and perhaps apocryphal manner of his ascendancy.

A certain Ikūn-pî-Ištar[nb 9] is recorded as having ruled for 6 months or a year, between the reigns of Erra-imittī and Enlil-bani according to two variant copies of a chronicle.[38] Another chronicle[i 32] which might have shed further light on his origins is too broken to translate.

Hegemony over Nippur was fleeting, with control of the city passing back and forth between Isin and Larsa several times. Uruk, too, seceded during his reign and, as his power crumbled, he may have had the Chronicle of Early Kings[i 33] redacted to provide a more legendary tale of his accession than the rather mundane act of usurpation that it may well have been.[38] It relates that Erra-Imittī selected his gardener, Enlil-bâni, enthroned him, and placed the royal tiara on his head. Erra-Imittī then died while eating hot porridge, and Enlil-bâni by virtue of his refusal to quit the throne, became king.[39]

The colophon of a medical text,[i 34] “when a man's brain contains fire,”[nb 10] from the Library of Ashurbanipal reads: “Proven and tested salves and poultices, fit for use, according to the old sages from before the flood[nb 11] from Šuruppak, which Enlil-muballiṭ, sage (apkallu) of Nippur, left (to posterity) in the second year of Enlil-bāni.”[40][41][42]

Enlil-bani found it necessary to "build anew the wall of Isin which had become dilapidated,"[i 35] which he recorded on commemorative cones. He named the wall Enlil-bāni-išdam-kīn,[i 36] “Enlil-bāni is firm as to foundation.” In practice, the walls of major cities were probably under continuous repair. He was a prodigious builder, responsible for the construction of the é-ur-gi7-ra, “the dog house,”[i 37] temple of Ninisina, a palace,[i 38] also the é-ní-dúb-bu, “house of relaxation,” for the goddess Nintinugga, “lady who revives the dead,”[i 39] the é-dim-gal-an-na, “house - great mast of heaven,”[i 40] for the tutelary deity of Šuruppak, the goddess Sud, and finally, the é-ki-ág-gá-ni for Ninibgal, the “lady with patient mercy who loves ex-votos, who heeds prayers and entreaties, his shining mother.”[i 41][43] Two large copper statues were taken to Nippur for dedication to Ningal, which Iddin-Dagān had fashioned 117 years earlier but had been unable to deliver, “on account of this, the goddess Ninlil had the god Enlil lengthen the life span of Enlil-Bāni.”[i 42][44]

There are perhaps two hymns addressed to this monarch.

Reign of Zambiya[edit]

Zambiya (fl. c. 1762—1759 BCE by the short chronology) was the 11th king of the Dynasty of Isin. He is best known for his defeat at the hands of Sin-iqišam, king of Larsa.

According to the SKL,[i 43] Zambiya reigned for 3 years.[45] He was a contemporary of Sin-iqišam king of Larsa, whose fifth and final year-name celebrates his victory over Zambiya: “year the army of (the land of) Elam (and Zambiya, (the king of Isin,)) was/were defeated by arms,” suggesting a confederation between Isin and Elam against Larsa. The city of Nippur was hotly contested between the city-states. If Zambiya survived this battle, he may have possibly gone on to be contemporary with Sin-iqišam's successors, Ṣilli-Adad and Warad-Sin.[46]

Reign of Iter-pisha[edit]

Iter-pisha (fl. c. 1759—1755 BCE by the short chronology) was the 12th king of the Dynasty of Isin. The SKL[i 44] tells us that "the divine Iter-pisha ruled for 4 years."[nb 12] The Ur-Isin King List[i 45] which was written in the 4th year of the reign of Damiq-ilišu gives a reign of just 3 years.[8] His relationships with his predecessor and successor are uncertain and his reign falls during a period of general decline in the fortunes of the dynasty.

He was a contemporary of Warad-Sin (ca. 1770 BCE to 1758 BCE) the king of Larsa, whose brother and successor, Rim-Sin I would eventually come to overthrow the dynasty, ending the cities' bitter rivalry around 40 years later. He is only known from Kings lists and year-name date formulae in several contemporary legal and administrative texts.[47] Two of his year-names refer to his provision of a copper Lilis for Utu and Inanna respectively, where Lilissu is a kettledrum used in temple rituals.[48]

He is perhaps best known for the literary work generally known as the letter from Nabi-Enlil to Iter-pisha formerly designated letter from Iter-pisha to a deity, when its contents were less well understood. It is extant in seven fragmentary manuscripts[i 46] and seems to be a petition to the king from a subject who has fallen on hard times.[49] It is a 24-line composition that had become a belle letter used in scribal education during the subsequent Old Babylonian period.[50]

Reign of Ur-du-kuga[edit]

Ur-du-kuga (fl. c. 1755—1751 BCE by the short chronology) was the 13th king of the Dynasty of Isin and reigned for 4 years according to the SKL,[i 47] 3 years according to the Ur-Isin kinglist.[i 48][29] He was the third in a sequence of short reigning monarchs whose filiation was unknown and whose power extended over a small region encompassing little more than the city of Isin and its neighbor Nippur. He was probably a contemporary of Warad-Sîn of Larsa and Apil-Sîn of Babylon.

He credited Dāgan, a god from the middle Euphrates region who had possibly been introduced by the dynasty's founder, Išbi-Erra, with his creation, in cones[i 49] commemorating the construction of the deity's temple, the Etuškigara, or the house “well founded residence,” an event also celebrated in a year-name. The inscription describes him as the “shepherd who brings everything for Nippur, the supreme farmer of the gods An and Enlil, provider of the Ekur…” This heaps profuse declarations of his care for Nippur's sanctuaries, the Ekur for Enlil, the Ešumeša for Ninurta and the Egalmaḫ for Gula, Ninurta's divine wife.[51]

A piece of brick from Isin,[i 50] bears his titulary but the event it marked has not been preserved. A cone shaft[i 51] memorializes the building of a temple of Lulal of the cultic city of Dul-edena, northeast of Nippur on the Iturungal canal.[52] The digging of the Imgur-Ninisin canal was celebrated in another year-name.

Reign of Sîn-māgir[edit]

Suen-magir (fl. c. 1751—1740 BCE by the short chronology) was the 14th king of the Dynasty of Isin and he reigned for 11 years.[i 52]

His reign falls over the last six years of Warad-Sin and the first five of Rim-Sin I, the sons of Kudur-Mabuk and successive kings of Larsa, and wholly within the reign of the Babylonian monarch Apil-Sin. There are currently six extant royal inscriptions, including brick palace inscriptions,[i 53] seals for his devoted servants, such as Iddin-damu, his “chief builder,” and Imgur-Sîn, his administrator, and a cone[i 54] which records the construction of a storehouse for the goddess Aktuppītum of Kiritab in his honor commissioned by Nupṭuptum, the lukur priestess or concubine, “his beloved traveling escort, mother of his first-born.”[10]

An inscription[i 55] marks the construction of a defensive wall, called Dūr-Suen-magir, “Suen-magir makes the foundation of his land firm,” at Dunnum, a city northeast of Nippur. Control of Nippur itself however may have shifted to Larsa, under the rule of Warad-Sîn and his father, Kudur-Mabuk, the power behind the throne, as his sixth year-name celebrates that he “had (14 copper statues brought into Nippur and) 3 thrones adorned with gold brought into the temples of Nanna, Ningal and Utu.” Larsa was to retain Nippur until year nine of Rīm-Sîn when it was lost to Damiq-ilišu. One of the cones bearing this inscription was found in the ruins of the temple of Ninurta, the é-ḫur-sag-tí-la, in Babylon, and is thought likely to have been an ancient museum piece. The city of Dunnum, the celebration of whose original foundation may have been the purpose of the Dynasty of Dunnum myth,[53] was taken by Rim-Sin the year before he conquered Isin and so it is conjectured that the cone was taken from Larsa as booty by Ḫammu-rapī.

Two legal tablets offered for private sale, recording sales of a storehouse and palm grove, give a year-name elsewhere unattested, “year Suen-magir the king dug the Ninkarrak canal.”[i 56] Another year-name marks "(Suen-magir) built on the bank of the Iturungal canal (the old wadi) a great fortification (called) Suen-magir-madana-dagal-dagal (Suen-magir broadens his country)." A province in the south and a town in eastern Babylonia near Tuplias are both called Bīt-Suen-magir and some historians have speculated one or other were named in his honor.[54]

Reign of Damiq-ilishu[edit]

Damiq-ilishu (fl. c. 1740—1717 BCE by the short chronology) was the 15th and final king of the Dynasty of Isin. He succeeded his father Sîn-māgir and reigned for 23 years.[i 57] Some variant king lists provide a shorter reign,[i 58] but it is thought that these were under preparation during his rule.[i 59][55] He was defeated first by Sîn-muballiṭ of Babylon (c. 1748 – 1729 BCE ) and then later by Rīm-Sîn I of Larsa, (c. 1758 – 1699 BCE).

His standard inscription characterizes him as the "farmer who piles up the produce (of the land) in granaries." Four royal inscriptions are extant including cones celebrating the building of the wall of Isin, naming him as “Damiq-ilišu is the favorite of the god Ninurta” also recollected in a year-name and “suitable for the office of en priest befitting the goddess Inanna.”[i 60] Construction of a storehouse e-me-sikil, “house with pure mes (rites?)”, for the god Mardu,[i 61] son of the god An. A cone records the construction of a temple, the é-ki-tuš-bi-du10, “House – its residence is good,” possibly for the deity Nergal of Uṣarpara. There is also a palace inscription and a copy of a dedication to Nergal of Apiak on a votive lion sculpture.[56]

An outline of the political events can be gleaned from an examination of the year names of the rival kingdoms. Rīm-Sîn's year 14 (c. 1744 BCE ) records "Year the armies of Uruk, Isin, Babylon, Sutum, Rapiqum, and of Irdanene,[nb 13] the king of Uruk, were smitten with weapons". This victory over a grand coalition seems to have awakened in Rīm-Sîn imperial ambitions. Damiq-ilišu's year 13 (c. 1739 BCE ) records the “Year in which (Damiq-ilišu) built the great city wall of Isin (called) 'Damiq-ilišu-hegal’ (Damiq-ilišu is abundance)". The holy city of Nippur seems to have been wrestled from the control of Larsa around 1749 BCE by Damiq-ilishu who held it until Rīm-Sîn reclaimed it around 1737 BCE, the year he "destroyed Uruk", based upon the dating of documents found there. Sin-muballit's year 13 (c. 1735 BCE) is called “Year the troops and the army of Larsa were smitten by weapons.” Rīm-Sîn's year 25 (c. 1733 BCE) is named “Year the righteous shepherd Rim-Sin with the powerful help of An, Enlil, and Enki seized the city of Damiq-ilišu, brought its inhabitants who had helped Isin as prisoners to Larsa, and established his triumph greater than before.” This setback seems to have crippled the tottering Isin state enabling Sîn-muballiṭ of Babylon to pillage the city in 1732 BCE, during his year 16.[nb 14][57]

Rīm-Sîn's year 29 (1729) recalls "Year in which Rīm-Sîn the righteous shepherd with the help of the mighty strength of An, Enlil, and Enki seized in one day Dunnum the largest city of Isin and submitted to his orders all the drafted soldiers but he did not remove the population from its dwelling place". His year 30 (c. 1728 BCE) reads “Year Rīm-Sîn the true shepherd with the strong weapon of An, Enlil, and Enki seized Isin, the royal capital and the various villages, but spared the life of its inhabitants, and made great for ever the fame of his kingship.” The event was considered so significant that from then on every year-name of Rīm-Sîn was named after it: the first year after the sack of Isin until “Year 31 after he seized Isin.”[26]

The Weidner Chronicle,[i 62] also called the Esagila Chronicle, is an apocryphal historiographical or supposititious letter composed in the name of Damiq-ilišu who addresses Apil-Sîn of Babylon (c. 1767 - 1749 BCE) discussing the merits of offerings made to Marduk on their donors. There is also a belle letter from Damiq-ilishu to the god Nuska. He seems to have become something of a folk-hero, because later kings hark back to him and describe themselves as his successor. The Sealand Dynasty seems to have considered itself the inheritor of the neo-Sumerian beacon and the 3rd king, Damqi-ilišu, even took his name. The founder of the 2nd Sealand Dynasty, Simbar-Šipak (c. 1025-1008 BCE), was described as “soldier of the dynasty of Damiq-ilišu,” in a historical chronicle.[i 63]

Timeline of rulers[edit]

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approximate dates (short) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ishbi-Erra | 33 years | fl. c. 1953—1920 BCE | Ishbi-Erra and his successors appear on the Sumerian King List. Contemporary of Ibbi-Suen of Ur. | ||

| Shu-Ilishu | "the son of Ishbi-Erra" | 20 years | fl. c. 1920—1900 BCE | ||

| Iddin-Dagan | "the son of Shu-ilishu" | 21 years | fl. c. 1900—1879 BCE | ||

| Ishme-Dagan | "the son of Iddin-Dagan" | 20 years | fl. c. 1879—1859 BCE | ||

| Lipit-Eshtar | "the son of Ishme-Dagan (or Iddin-Dagan)" | 11 years | fl. c. 1859—1848 BCE | Contemporary of Gungunum of Larsa. | |

| Ur-Ninurta | "the son of Ishkur, may he have years of abundance, a good reign, and a sweet life" | 28 years | fl. c. 1848—1820 BCE | Contemporary of Abisare of Larsa. | |

| Bur-Suen | "the son of Ur-Ninurta" | 21 years | fl. c. 1820—1799 BCE | ||

| Lipit-Enlil | "the son of Bur-Suen" | 5 years | fl. c. 1799—1794 BCE | ||

| Erra-imitti | 8 years | fl. c. 1794—1786 BCE | He appointed his gardener, Enlil-Bani, substitute king and then suddenly died. | ||

| Enlil-bani | 24 years | fl. c. 1786—1762 BCE | Contemporary of Sumu-la-El of Babylon. He was Erra-imitti's gardener and was appointed substitute king, to serve as a scapegoat and then sacrificed, but remained on the throne when Erra-imitti suddenly died. | ||

| Zambiya | 3 years | fl. c. 1762—1759 BCE | Contemporary of Sin-Iqisham of Larsa. | ||

| Iter-pisha | 4 years | fl. c. 1759—1755 BCE | |||

| Ur-du-kuga | 4 years | fl. c. 1755—1751 BCE | |||

| Suen-magir | 11 years | fl. c. 1751—1740 BCE | Suen-magir appears as the last ruler on the Sumerian King List | ||

| (Damiq-ilishu)* | ("the son of Suen-magir")* | (23 years)* | fl. c. 1740—1717 BCE |

- These epithets or names are not included in all versions of the SKL.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ The spelling of royal names follows the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- ^ George, A. R. Sumero-Babylonian King Lists and Date Lists (PDF). pp. 206–210.

- ^ a b Marc Van De Mieroop (2015). A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 87.

- ^ Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels, eds. (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 469.

- ^ S. N. Kramer (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. pp. 93–94.

- ^ C. J. Gadd (1971). "Babylonia, 2120-1800 B.C.". In I. E. S. Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 1, Part 2: Early History of the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 612–615.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.) RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia (Book 4). University of Toronto Press. pp. 6–11.

- ^ a b Jöran Friberg (2007). A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts: Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection: Cuneiform Texts. Springer. pp. 131–134.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts (1999). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 149.

- ^ a b c Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4. University of Toronto Press. pp. 97–1.

- ^ William W. Hallo (2009). The World's Oldest Literature. Brill. p. 206.

- ^ Marc Van de Mieroop (1987). Crafts in the Early Isin Period: A Study of the Isin Craft Archive from the Reigns of Išbi-Erra and Šu-Illišu. Peeters Publishers. pp. 1, 117–118.

- ^ Marc Van de Mieroop (1986). "Nippur texts from the early Isin period". JANES (18): 35–36.

- ^ D. O. Edzard (1999). Erich Ebeling; Bruno Meissner (eds.). Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie: Ia - Kizzuwatna. Vol. 5. Walter De Gruyter Inc. pp. 30–31.

- ^ David I Owen (October 1971). "Incomplete date formulae of Iddin-Dagān again". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. XXIV (1–2): 17. doi:10.2307/1359342. JSTOR 1359342.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts (1999). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. pp. 149, 162.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian period (2003-1595 BC): Early Periods, Volume 4 (RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia). University of Toronto Press. pp. 77–90.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian period (2003-1595 BC): Early Periods, Volume 4 (RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia). University of Toronto Press. pp. 64–68.

- ^ William J. Hamblin (2007). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Taylor & Francis. p. 164.

- ^ M. Fitzgerald (2002). The Rulers of Larsa. Yale University Dissertation. p. 55.

- ^ M. Stol (May 1982). "A Cadastral Innovation by Hammurabi". In G. van Driel (ed.). Assyriological Studies presented to F. R. Kraus on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Netherlands Institute for the Near East. p. 352.

- ^ James Bennett Pritchard, Daniel E. Fleming (2010). The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press. pp. 190–191.

- ^ Paul-Alain Beaulieu (2007). Richard J. Clifford (ed.). Wisdom literature in Mesopotamia and Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 6.

- ^ Jöran Friberg (2007). A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts: Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection: Cuneiform Texts. Springer. pp. 231–235.

- ^ A. R. George (2011). Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection. CDL Press. p. 93.

- ^ a b c M. Fitzgerald (2002). The Rulers of Larsa. Yale University Dissertation. pp. 55–75.

- ^ a b Anne Goddeeris (2009). Tablets from Kisurra in the Collections of British Museum. Harrassowitz.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian period (2003-1595 BC): Early Periods, Volume 4 (RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia). University of Toronto Press. pp. 69–74.

- ^ a b Jöran Friberg (2007). A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts: Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection: Cuneiform Texts. Springer. pp. 231–234.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4. University of Toronto Press. p. 75.

- ^ William W Hallo (2009). The World's Oldest Literature: Studies in Sumerian Belles Lettres. Brill. pp. 185–186.

- ^ William W Hallo (1979). "God, king and man at Yale". State and Temple Economy in the Ancient Near East, Volume I. Peeters Publishers. p. 104.

- ^ Aaron Shaffer (1974). "Enlilbani and the 'Dog House' in Isin". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 26 (4): 251–255. doi:10.2307/1359444. JSTOR 1359444.

- ^ Anne Goddeeris (2009). Tablets from Kisurra in the Collections of British Museum. Harrassowitz. p. 16.

- ^ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of The Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia. Routledge. p. 391.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4. University of Toronto Press. p. 76.

- ^ Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Greenwood Press. p. 189.

- ^ a b Jean-Jacques Glassner (2005). Mesopotamian Chronicles. SBL. pp. 107–108, 154. Glassner's manuscript’s C and D.

- ^ Simo Parpola (2009). Letters from Assyrian Scholars to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal: Commentary and Appendix No. 2. Eisenbrauns. p. XXVI.

- ^ Alan Lenzi (2008). "The Uruk List of Kings and Sages and Late Mesopotamian Scholarship". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 8 (2): 150. doi:10.1163/156921208786611764.

- ^ William W Hallo (2009). The World's Oldest Literature: Studies in Sumerian Belles Lettres. Brill. p. 703.

- ^ R. Campbell Thompson (1923). Assyrian medical texts from the originals in the British Museum. Oxford University Press. pp. iii, 104–105. for line art.

- ^ A. Livingstone (1988). "The Isin "Dog House" Revisited". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 40 (1): 54–60. doi:10.2307/1359707. JSTOR 1359707.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian period (2003-1595 BC): Early Periods, Volume 4 (RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia). University of Toronto Press. pp. 77–90.

- ^ Jöran Friberg (2007). A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts: Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection: Cuneiform Texts. Springer. p. 231.

- ^ Marten Stol (1976). Studies in Old Babylonian history. Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te İstanbul. p. 15.

- ^ D. O. Edzard (1999). Dietz Otto Edzard (ed.). Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie: Ia – Kizzuwatna. Vol. 5. Walter De Gruyter. p. 216.

- ^ Dahlia Shehata (2014). "Sounds From The Divine: Religious Musical Instruments In The Ancient Near East". In Joan Goodnick Westenholz; Yossi Maurey; Edwin Seroussi (eds.). Music in Antiquity: The Near East and the Mediterranean. Walter de Gruyter. p. 115.

- ^ Pascal Attinger (2014). "40) Nabu-Enlil-Īterpīša (ANL 7)". Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires (NABU) (2): 165–168.

- ^ Eleanor Robson (2001). "The tablet House: a scribal school in old Babylonian Nippur". Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 93 (1): 58. doi:10.3917/assy.093.0039.

- ^ Frans van Koppen (2006). Mark William Chavalas (ed.). The ancient Near East: historical sources in translation. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 90–91.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4. University of Toronto Press. pp. 94–96.

- ^ Ewa Wasilewska (2001). Creation stories of the Middle East. Jessica Kingsley Pub. p. 90.

- ^ William McKane (2000). A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Jeremiah, Vol. 2: Commentary on Jeremiah, XXVI-LII. T&T Clark Int'l. pp. 974–975.

- ^ Jöran Friberg (2007). A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts: Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection: Cuneiform Texts. Springer. pp. 233–235.

- ^ Douglas Frayne (1990). Old Babylonian period (2003-1595 BC): Early Periods, Volume 4 (RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia). University of Toronto Press. pp. 102–106.

- ^ M. Fitzgerald (2002). The Rulers of Larsa. Yale University Dissertation. pp. 139–144.

Notes[edit]

- ^ WB 444, the Weld-Blundell prism, r. 33.

- ^ Tablet UM 7772.

- ^ CBS 2272, letter from Ishbi-Erra to Ibbi-Sin.

- ^ Tablets NBC 6421. 7087. 7387.

- ^ IM 58336, Construction of a great lyre for Enlil.

- ^ Sumerian King List, MS 1686.

- ^ Such as WB 444, the Weld-Blundell prism.

- ^ Tablets CBS 14074, Ni 2482 and N 2833.

- ^ Tablet UM 55-21-125, University Museum, Philadelphia.

- ^ Prism AO 8864, Louvre.

- ^ Sumerian King List extant in 16 copies.

- ^ Tablet UM 55-21-102, University Museum, Philadelphia.

- ^ Dynastic list of the kings of Awan and Simashki, Sb 17729 in the Louvre.

- ^ Išbi-Erra and Kindattu, tablets N 1740 + CBS 14051.

- ^ MM 1974.26 Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm.

- ^ Tablets IM 85467 and IM 85466, National Museum of Iraq.

- ^ Excavation number U 2682.

- ^ Tablet UM L-29-578, University Museum Philadelphia.

- ^ VAT 8212.

- ^ Extant on numerous bricks, for example BM 90378.

- ^ CBS 12694.

- ^ Sumerian King List extant in 16 copies.

- ^ Sumerian King List, WS 444, the Weld Blundell prism.

- ^ Ur-Isin king list MS 1686.

- ^ For example, brick CBS 8642 from Nippur and brick IM 76546 from Isin.

- ^ Formerly in collection of Frau G. Strauss.

- ^ LB 2120 in the Lagre Böhl collection.

- ^ The Sumerian King List Ash. 1923.444, the Wend-Blundell prism.

- ^ MS 1686, the Ur-Isin king list.

- ^ Cylinder seal BM 130695.

- ^ Ur-Isin kinglist line 15.

- ^ The Babylonian chronicle fragment 1 B ii 1-8.

- ^ Chronicle of early kings A 31-36, B 1-7.

- ^ Tablet K.4023 column iv lines 21 to 25.

- ^ Cones IM 77922, CBS 16200, and 8 others.

- ^ Two cones, IM 10789 and UCLM 94791.

- ^ Cone 74.4.9.249 and another in a private collection in Wiesbaden.

- ^ Clay impression, IM 25874.

- ^ Cone in Chicago A 7555.

- ^ IM 79940.

- ^ NBC 8955 and A 7461 inscription on two cones.

- ^ Tablet UM L-29-578.

- ^ The Sumerian King List, WB 444, Ash. 1923.444, the Weld-Blundell prism.

- ^ Sumerian King List, Ash. 1923.444, the "Weld-Blundell Prism."

- ^ Ur-Isin King List tablet MS 1686.

- ^ Tablets UM 55-21-329 +, 3N-T0901,048, 3N-T 919,455, CBS 7857, UM 55-21-323, and CBS 14041 + in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and MS 2287 in the Schøyen Collection.

- ^ Sumerian King List, Ashm. 1923.344 the Blund-Wendell prism.

- ^ Ur-Isin kinglist, tablet MS 1686 line 18.

- ^ Cones LB 990, NBC 6110, 6111, 6112.

- ^ Brick IB 1337.

- ^ Cone IM 95461, found in Isin.

- ^ Sumerian King Lists Ash. 1923.444 and CBS 19797 and Ur-Isin king list MS 1686.

- ^ Brick, IM 78635.

- ^ Cone A 16750.

- ^ IB 1610, from Isin, a complete cone and VA Bab 628, 609, from Babylon, parts of a single cone.

- ^ Tablets with dealer references LO.1250 and LO.1253.

- ^ CBS 19797, published as Hilprecht’s BE 20 no. 47 (1906).

- ^ The ‘’Ur-Isin king list’’, MS 1686 gives 4 years.

- ^ Ash. 1923.444 does not list him.

- ^ HS 2008 & CBS 9999 (Nippur), IB 1090 (Isin).

- ^ Cone A7556.

- ^ Weidner Chronicle (ABC 19).

- ^ Dynastic Chronicle (ABC 18) v 3.

- ^ lugal-kala-ga, lugal-i-si-in-KI-ga (lugal-KI-úri-ma), lugal-KI-en-gi-KI-uri-ke4.

- ^ mu dI-dan dDa-gan lugal-e [Ma]-tum-ni-a-tum [dumu-mí]-a-ni lugal An-ša-an(a)[ki] ba-an-tuk-a.

- ^ mu ur-dnin-urta ba-gaz.

- ^ mu ur-dnin-urta ba-ugà.

- ^ mu ús.sa dUr-dNin.urta lugal.e a.gàr gal.gal a.ta im.ta.an.e11 mu.ús.sa.bi.

- ^ BM 85348: mu ús-sa ki-sur-raki dÌr-ra-i-mi-ti ba-an-dib.

- ^ YOS 14 319: mu dÌr-ra-i-mi-ti bàd ka-zal-luki ba-gal.

- ^ NU-NÍG-SAG-ÍL-e.

- ^ I-k[u-un]-pi-Iš8-tár.

- ^ Enuma amelu muḫḫu-šu išata u-kal.

- ^ (21) [na]p-šá-la-tú tak-ṣi-ra-nu lat-ku-tu4 ba-ru-ti šá ana [Š]u šu-ṣú-ú (22) šá KA NUN.ME.MEŠ-e la-bi-ru-ti šá la-am A.MÁ.URU5(abūbi) (23) šá ana LAMXKURki(šuruppak) MU.2.KÁM IdEN.LĺL-ba-ni LUGAL uruÌ.ŠI.INki (24) IdEN.LĺL-mu-bal-liṭ NUN.ME NIBRUki [ez]-bu.

- ^ di.te.er.pi4.ša mu 4 i.ak.

- ^ Alternative reading of the name: Irnene.

- ^ Year 16 of Sîn-muballiṭ as recorded at CDLI, Fitzgerald says year 17.