Effects of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation in Australia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Effects of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation in Australia are present across most of Australia, particularly the north and the east, and are one of the main climate drivers of the country. Associated with seasonal abnormality in many areas in the world, Australia is one of the continents most affected and experiences extensive droughts alongside considerable wet periods that cause major floods. There exist three phases — El Niño, La Niña, and Neutral, which help to account for the different states of ENSO.[1] Since 1900, there have been 28 El Niño and 19 La Niña events in Australia including the current 2023 El Niño event, which was declared on 17th of September in 2023.[2][3][4][5] The events usually last for 9 to 12 months, but some can persist for two years, though the ENSO cycle generally operates over a time period from one to eight years.[6]

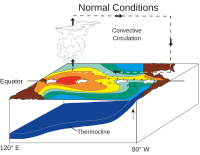

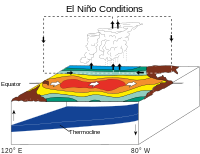

Through La Niña years the eastern seaboard of Australia records above-average rainfall usually creating damaging floods due to stronger easterly trade winds from the Pacific towards Australia, thus increasing moisture in the country. Conversely, El Niño events will be associated with a weakening, or even a setback, of the prevailing trade winds, and this, results in reduced atmospheric moisture in the country.[7] Many of the worst bushfires in Australia accompany ENSO events, and can be exacerbated by a positive Indian Ocean Dipole, where they would tend to cause a warm, dry and windy climate.[8]

Climate Modelling[edit]

The Bureau of Meteorology is Australia’s governing body for monitoring climate drivers and model data. All climate models developed at leading international climate agencies are utilised by the Bureau for climate driver monitoring and data sourcing. All models use an ensemble method, where several forecasts are run at the same time using slightly different initial conditions. While all models use ensemble techniques, the number of ensembles differs for each model.[9] The Climate Model Summary is updated on the 12th of each month (or the next working day following the 12th) when model data becomes available. Data for the Bureau's model, ACCESS–S, is updated fortnightly along with several other models that also provide more frequent updates during the month.[9]

Impacts[edit]

El Niño[edit]

El Niño episodes are defined as continuous warming of the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, thus resulting in a decrease in the strength of the Pacific trade winds, and a reduction in rainfall over eastern and northern Australia, particularly in winter and spring. An El Niño event typically begins in autumn and fully forms during winter and spring, but would then would start to dissipate by summer, with the event usually concluding in the autumn of the next year. Snow depth during El Niño years is generally lower in Australia's alpine regions.[10]

Furthermore, El Niño years generally experience warmer-than-average temperatures with hotter daily temperature extremes across the south, especially in spring and summer. Even though temperature maxima is occasionally warmer than average, reduced cloud cover frequently produces a cooler temperature minimum during winter-spring and a longer frost season.

El Niño's effect on Australian rainfall decreases after November, particularly in the southeast, and therefore a pronounced difference between the rainfall patterns of early and late summer would exist. Nonetheless, Cape York and northwest Tasmania would have moderately dry conditions. Some areas on the Queensland/New South Wales border exhibit a small inclination for wetter conditions. There is also a reasonably stronger propensity for wetter than average conditions in the southeast of Western Australia.[11]

La Niña[edit]

La Niña episodes are defined as uninterrupted cooling of the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, thus resulting in an increase in the strength of the Pacific trade winds, and the opposite effects in Australia when compared to El Niño. In the La Niña case, the convective cell over the western Pacific strengthens inordinately, resulting in colder than normal winters in North America and a more intense cyclone season in South-East Asia and Eastern Australia with above-average winter–spring rainfall. There is a strong correlation between the strength of La Niña and rainfall: the greater the sea surface temperature and Southern Oscillation difference from normal, the larger the rainfall change.[12]

La Niña is characterised by increased rainfall and cloud cover, especially across the east and north that continue into the warm months (unlike El Niño events); the average December–March precipitation is 20% higher than the long-term average, particularly in the east coast. Snow depth and snow cover is increased in the southeast during winter. There are also cooler daytime temperatures south of the tropics (especially during the second half of the year) and fewer extreme highs, and warmer overnight temperatures in the tropics. There is less risk of frost,[13] but increased risk of widespread flooding, tropical cyclones, and the monsoon season starts earlier.[14] La Niña Modoki leads to a rainfall increase over northwestern Australia and northern Murray–Darling basin, rather than over the east as in a conventional La Niña.[15]

SOI and IOD[edit]

The Southern Oscillation is the atmospheric component of El Niño. This component is an oscillation in surface air pressure between the tropical eastern and the western Pacific Ocean waters. The strength of the Southern Oscillation is measured by the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI). The SOI is computed from fluctuations in the surface air pressure difference between Tahiti (in the Pacific) and Darwin, Australia (on the Indian Ocean): El Niño episodes with negative SOI means there is lower pressure over Tahiti and higher pressure in Darwin; La Niña episodes with positive SOI means there is higher pressure in Tahiti and lower in Darwin.[7]

In several recent studies, it is shown that the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) has a much more significant effect on the rainfall patterns in south-east Australia than the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in the Pacific Ocean.[16][17][18] It is further demonstrated that IOD-ENSO interaction is a key for the generation of Super El Ninos.[19] When an El Niño occurs with a positive IOD, the two events can strengthen their dry impact. Similarly, when La Niña coexists with a negative IOD, the chance of above-average winter–spring rainfall generally increases.[20]

History[edit]

Paleoclimate record[edit]

During the Last Glacial Maximum, around 45,000 years ago, moisture variability in the Australian core shows dry periods related to frequent warm events (El Niño), correlated to DO events. Although no strong correlation was found with the Atlantic Ocean, it is suggested that the insolation influence probably affected both oceans, although the Pacific Ocean seems to have the most influence on teleconnection in annual, millennial and semi-precessional timescales.[21]

1880s–1920s[edit]

1885 to 1898 were mostly La Niña years, being generally wet, though less so than in the period since 1968. The only noticeably dry years in this era were 1888 and 1897. Although some coral core data[22] suggest that 1887 and 1890 were the wettest years across the continent since settlement.[23] In New South Wales and Queensland, however, the years 1886–1887 and 1889–1894 were indeed exceptionally wet La Niña years, and February 1893 saw the disastrous 1893 Brisbane flood.[24]

1903–04 were La Niña years, which followed the Federation drought, though two major El Niño events in 1902 and 1905 produced the two driest years across the whole continent, whilst 1919 was similarly dry in the eastern states apart from the Gippsland. 1906–07 were moderate La Niña years with above-average rainfalls. 1909 to early 1911 were strong La Niña years. The 1911–1915 period were El Niño years, where the country suffered a major drought. Drying of the climate took place from 1899 to 1921, though with some interruptions from wet El Niño years, especially between 1915 and 1916–18 and 1924–25, and 1928.[25]

1920s–1960s[edit]

The period from 1922 to 1937 was particularly dry with most years having a positive El Niño phase, with only 1930 having Australia-wide rainfall above the long-term mean and the Australia-wide average rainfall for these seventeen years being 15 to 20 percent below that for other periods since 1885. This dry period is attributed in some sources to a weakening of the Southern Oscillation[26] and in others to reduced sea surface temperatures.[27] During World War II, eastern Australia suffered El Niño conditions which lasted from 1937 through to 1947 with little relief, despite a few weak and relatively dry La Niña years in between (1938–39 and 1942–43).[28]

1949–51 were La Niña years, which had significant rain events in central New South Wales and most of Queensland: Dubbo's 1950 rainfall of 1,329 mm (52.3 in) can be estimated to have a return period of between 350 and 400 years, whilst Lake Eyre filled for the first time in thirty years. 1954–57 were also intense La Niña years. In contrast, 1951–52, 1961 and 1965 were very dry, with complete monsoon failure in 1951–52 and extreme drought in the interior during 1961 and 1965. 1964–69 were moderate La Niña years. Conditions had been dry over the centre of the continent since 1957 but spread elsewhere during the summer of 1964–65. The El Niño conditions from 1965–70 contributed to the 1967 Tasmanian fires.[29]

1970s–1990s[edit]

The wettest periods in this century have been from 1973 to 1976, peaking in 1974, all La Niña years. The drought in 1979–83 is regarded as the worst of the twentieth century for short-term rainfall deficiencies of up to one year and their over-all impact. An El Niño event brought severe dust storms in north-western Victoria and severe bushfires in south-east Australia in February 1983.[30] This El Niño-related drought ended in March, when a monsoon depression became an extratropical low and swept across Australia's interior and on to the south-east in mid-to late March. 1987–88 were weak El Niño years, with 1988–89 featuring a strong La Niña event affecting the southeast half of the country.

Most of the 1990's were characterised by El Niño events; Beginning in the second half of 1991, a very severe drought occurred throughout Queensland which intensified in 1994 and 1995 to become the worst on record.[31][32][33] From July to August 1995 the drought was further influenced by a strong El Niño weather pattern associated with high temperatures.[34][35][36][32][37] Dry conditions began to emerge in south-eastern Australia during late 1996 and accentuated during the strong 1997 El Niño event. Despite the fact that the 1990s mostly consisted of El Niño years, a La Niña event formed from May 1998 where, in April 1999, it brought the notorious 1999 Sydney hailstorm.[38][39]

2000s[edit]

The 35 months from May 1998 to March 2001 can be considered a long La Niña phase, although much of eastern Australia experienced a dry 2001.[40] 2002 was one of Australia's driest and warmest years on record, with 'remarkably widespread' dry conditions, particularly in the eastern half of the country which was again affected by El Niño conditions. It was, at the time, Australia's fourth-driest year since 1900.[41] The El Niño weather pattern broke down by 2004, but occasional strong rainfall in 2003 and 2004 failed to alleviate the cumulative effect of persistently low rainfall in south-eastern Australia.[42][43]

South-east Australia experienced its second-driest year on record in 2006, an El Niño year, particularly affecting the major agricultural region of the Murray–Darling basin.[44] In early 2007, forecasters believed that the El Niño effect that had been driving the drought since 2006 had ended, though the Murray–Darling Basin experienced their seventh consecutive year of below-average rain.[45][46] Wildfires such as the 2003 Canberra bushfires in January and the worst bushfires in Australian history, which occurred on Black Saturday in February 2009, were intensified when combined with a positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) event.[47]

Although 2007 to early 2009 were moderate La Niña years, hot and dry conditions still prevailed in parts of south-eastern Australia, with occasional heavy rainfall failing to break the continuing drought.[48] The effects of the drought were exacerbated by Australia's (then) second-hottest year on record in 2009, with record-breaking heatwaves in January, February, and the second half of the year, when El Niño conditions returned, which also brought a powerful dust storm in the east.[49]

2010s[edit]

According to the Bureau of Meteorology's 2011 Australian Climate Statement, Australia had lower than average temperatures in 2011 as a consequence of a La Niña weather pattern.[50] During the 2010–2012 La Niña event, Australia experienced its second- and third-wettest years, since a record of the rainfall started to kept during 1900. It caused Australia to experience its wettest September on record in 2010, and its second-wettest year on record in 2010.[51] It also led to an unusual intensification of the Leeuwin Current.[52]

El Niño conditions developed in mid-2013 through much of western Queensland.[53] Although these began easing for western Queensland in early 2014, drought began to develop further east, along the coastal fringe and into the ranges of southeast Queensland and northeast New South Wales.[54] Warm and dry conditions continued into 2015 in the east, particularly in Queensland where the monsoon rains were delayed.[55] The 2013 New South Wales bushfires occurred in a neutral ENSO year, as not all major fires occur in El Niño years.[56]

By the start of spring in 2015, the Indian Ocean had started to help the El Niño, which resulted in Australia's third-driest spring on record and limited growth at the end of cropping season. The combination of heat and low rainfall brought a very early start to the 2015–16 Australian bushfire season, with over 125 fires burning in Victoria and Tasmania during October.[57] During the 2014–2016 El Niño event, the 2015–16 Australian region cyclone season was the least active since reliable records started during 1950s.[58][59]

Mild La Niña conditions were present from April to November 2016. Moderate, albeit brief, La Niña conditions returned in the summer of 2017–18.[60] Despite a few and short-lived La Niña outbursts, 2017–19 mostly consisted of El Niño conditions and had caused drier than average conditions for much of inland Queensland, most of New South Wales, eastern and central Victoria, and all of Tasmania.[61] In 2018, rainfall for the year was very low over the southeastern quarter of the Australian mainland.[62] Exacerbating the effects of diminished rainfall during the 2018 El Niño year were a record-breaking run of above-average monthly temperatures, with the first half of 2019 being on an El Niño alert.[63]

2020s–present[edit]

Although the unusually powerful 2019–20 Australian bushfire season was one of the most destructive bushfire seasons on record, it occurred in a neutral ENSO period and was rather intensified by a strong positive IOD.[64] La Niña conditions began to take effect in the 2020-21 summer, which resulted in the coolest summer in nine years and wettest in four years (with 29% more rainfall than average).[65] The La Niña event, although weak, caused the floods in March in southeastern Australia,[66] which led to above-average rainfall and flooding in the Hawkesbury-Nepean catchment and on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales.[67]

November 2021 was one of the wettest on record across some areas in eastern and northern Australia, after a La Niña was officially declared for the 2021–22 summer, making it the first back-to-back La Niña event since 2010–12.[68] Moreover, the summer of 2021–22 in Sydney was the wettest in 30 years due to the persisting La Niña conditions.[69] From late February to early March 2022, southeastern Queensland and northeastern New South Wales experienced significant rainfalls and flooding, which marked the phase of two years of wet La Niña summers in eastern Australia.[70][71][72]

After the floods in July 2022 in New South Wales, La Niña was declared once again for spring as higher than above average rainfall was recorded in October in New South Wales, making it the third La Niña event in a row.[73][74] In March 2023, La Niña was officially declared over in Australia, with sea surface temperatures returning to normal or neutral.[75] In July 2023, the World Meteorological Organization declared that El Niño has developed in the tropical Pacific for the first time in 7 years.[76] In September 2023, the Bureau of Meteorology formally declared an El Niño weather event, for the first time in 8 years, after hot and dry conditions prevailed over south-east Australia during spring.[77]

See also[edit]

- Climate of Australia

- Climate change in Australia

- Drought in Australia

- Floods in Australia

- Bushfires in Australia

References[edit]

- ^ The beasts to our east: What are El Ninos and La Ninas? By Peter Hannam from the Sydney Morning Herald, December 29, 2020.

- ^ La Niña In Australia Bureau of Meteorology. www.bom.gov.au

- ^ El Niño in Australia Bureau of Meteorology. www.bom.gov.au

- ^ "Climate Driver Update". Bureau of Meteorology. Bureau of Meteorology. 17 September 2023.

- ^ King, Andrew (13 September 2022). "La Niña, 3 years in a row: a climate scientist on what flood-weary Australians can expect this summer". The Conversation.

- ^ What is La Nina and what does it mean for your summer? By Peter Hannam and Laura Chung. The Sydney Morning Herald. November 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Climate glossary — Southern Oscillation Index (SOI)". Bureau of Meteorology (Australia). 2002-04-03. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ^ Australian Climate Extremes – Fire, BOM. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- ^ a b "Model Summary". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "What is La Niña and how does it impact Australia?". Bureau of Meteorology. www.bom.gov.au. Australian Government. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Climate Driver Update www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Power, Scott; Haylock, Malcolm; Colman, Rob; Wang, Xiangdong (1 October 2006). "The Predictability of Interdecadal Changes in ENSO Activity and ENSO Teleconnections". Journal of Climate. 19 (19): 4755–4771. Bibcode:2006JCli...19.4755P. doi:10.1175/JCLI3868.1. ISSN 0894-8755. S2CID 55572677.

- ^ Fewer frosts. Bureau of Meteorology.

- ^ Kuleshov, Y.; Qi, L.; Fawcett, R.; Jones, D. (2008). "On tropical cyclone activity in the Southern Hemisphere: Trends and the ENSO connection". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (14). S08. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3514S08K. doi:10.1029/2007GL032983. ISSN 1944-8007.

- ^ Cai, W.; Cowan, T. (2009). "La Niña Modoki impacts Australia autumn rainfall variability". Geophysical Research Letters. 36 (12): L12805. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..3612805C. doi:10.1029/2009GL037885.

- ^ Behera, Swadhin K.; Yamagata, Toshio (2003). "Influence of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the Southern Oscillation". Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. 81 (1): 169–177. Bibcode:2003JMeSJ..81..169B. doi:10.2151/jmsj.81.169.

- ^ Annamalai, H.; Xie, S.-P.; McCreary, J.-P.; Murtugudde, R. (2005). "Impact of Indian Ocean sea surface temperature on developing El Niño". Journal of Climate. 18 (2): 302–319. Bibcode:2005JCli...18..302A. doi:10.1175/JCLI-3268.1. S2CID 17013509.

- ^ Izumo, T.; Vialard, J.; Lengaigne, M.; de Boyer Montegut, C.; Behera, S.K.; Luo, J.-J.; Cravatte, S.; Masson, S.; Yamagata, T. (2010). "Influence of the state of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the following year's El Niño" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 3 (3): 168–172. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..168I. doi:10.1038/NGEO760.

- ^ Hong, Li-Ciao; LinHo; Jin, Fei-Fei (2014-03-24). "A Southern Hemisphere booster of super El Niño". Geophysical Research Letters. 41 (6): 2142–2149. Bibcode:2014GeoRL..41.2142H. doi:10.1002/2014gl059370. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 128595874.

- ^ Indian Ocean influences on Australian climate - When the Indian and Pacific oceans work together The Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Turney, Chris S. M.; Kershaw, A. Peter; Clemens, Steven C.; Branch, Nick; Moss, Patrick T.; Fifield, L. Keith (2004). "Millennial and orbital variations of El Niño/Southern Oscillation and high-latitude climate in the last glacial period". Nature. 428 (6980): 306–310. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..306T. doi:10.1038/nature02386. PMID 15029193. S2CID 4303100.

- ^ "Commentary on rainfall probabilities based on phases of the SOI". www.longpaddock.qld.gov.au. Department of Environment and Resource Management. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ashcroft, Linden; Gergis, Joëlle; Karoly, David John (November 2014). "A historical climate dataset for southeastern Australia, 1788–1859". Geoscience Data Journal. 1 (2): 158–178. Bibcode:2014GSDJ....1..158A. doi:10.1002/gdj3.19.

- ^ Foley, J.C.; Droughts in Australia: review of records from earliest years of settlement to 1955; published 1957 by Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- ^ "The 1914–15 drought". Climate Education. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 1999. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^ Allan, R.J.; Lindesay, J. and Parker, D.E.; El Niño, Southern Oscillation and Climate Variability; p. 70. ISBN 0-643-05803-6

- ^ "Soils and landscapes near Narrabri and Edgeroi, NSW, with data analysis using fuzzy k-means" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-13. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ^ "The World War II droughts 1937–45". Climate Education. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 1999. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^ "The 1965–68 drought". Climate Education. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 1999. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^ "Short but sharp – The 1982–83 droughts". Climate Education. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- ^ Rankin, Robert. (1992) Secrets of the Scenic Rim. Rankin Publishers ISBN 0-9592418-3-3 (page 151)

- ^ a b Collie, Gordon (26 August 1995). "Worst drought of century cripples farmers". The Courier-Mail. p. 14.

- ^ Collie, Gordon. Dry tears of despair. The Courier-Mail. p. 29. 22 October 1994.

- ^ Collie, Gordon. Water crisis threatens towns. The Courier Mail p. 3. 3 June 1995

- ^ Coleman, Matthew (30 August 1995). "Crops worth $50m lost". The Courier-Mail.

- ^ Rankin, Robert (1992). Secrets of the Scenic Rim: A Bushwalking and Rockclimbing Guide to South-east Queensland's Best Mountainous Area. Rankin. p. 151. ISBN 0-9592418-3-3.

- ^ Collie, Gordon (3 June 1995). "Water crisis threatens towns". The Courier Mail. p. 3.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 February 1998). "1998 Yearbook – Climate Variability and El Nino". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Australian rainfall during El Niño and La Niña events www.bom.gov.au Bureau of Meteorology

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology (3 January 2002). "Annual Australian Climate Summary 2001". www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "Annual Australian Climate Summary 2002". www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "Annual Australian Climate Summary 2004". www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2005". www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "Annual Climate Statement 2006". www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Barlow, Karen (22 February 2007). "El Nino declared over". Water. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

The Bureau of Meteorology has declared that the El Nino which has made the drought so much worse for the past year or so has passed. A senior climatologist at the Bureau of Meteorology, Grant Beard, says it's time to be optimistic about drought-breaking rains, although the drought is far from over yet.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2007". www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ "Police: Australian fires create 'a holocaust'". CNN. 9 February 2009.

- ^ Australian rainfall during El Niño and La Niña events www.bom.gov.au. Bureau of Meteorology.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2009". www.bom.gov.au. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2011". Bom.gov.au. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ "The 2010–11 La Niña: Australia soaked by one of the strongest events on record". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Feng, Ming; McPhaden, Michael J.; Xie, Shang-Ping; Hafner, Jan (14 February 2013). "La Niña forces unprecedented Leeuwin Current warming in 2011 : Scientific Reports : Nature Publishing Group". Nature.com. 3 (1): 1277. doi:10.1038/srep01277. PMC 3572450. PMID 23429502. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "Rainfall deficiencies increase in Queensland and northeastern New South Wales". Climate: Drought: Archive. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Rainfall deficiencies increase in Queensland and northeastern New South Wales". Climate: Drought: Archive. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2015". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ What is Niño and how does it impact Australia? Bureau of Meteorology, issued June 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Cook, Alison; Watkins, Andrew B; Trewin, Blair; Ganter, Catherine (May 2016). "El Niño is over, but has left its mark across the world". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016.

- ^ Dry and hot in the northern tropics (Report). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. May 2016. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ 2015–16 southern hemisphere wet-season review (Report). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 10 May 2016. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ ENSO Outlook - An alert system for the El Niño–Southern Oscillation Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2017". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2018". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Australia records three years of hotter than average monthly temperatures Sydneys Kiss FM, 5 November 2019.

- ^ "Australia fires: Life during and after the worst bushfires in history". BBC News. 28 April 2020.

- ^ What is the meaning of La Niña and how will the weather event affect Australia’s summer? www.theguardian.com

- ^ La Nina set to be declared: The dangerous change to Australia’s weather by Benedict Brook from News.com.au. November 16, 2021.

- ^ "How NSW's devastating floods stack up against past deluges". www.abc.net.au. 2021-03-25. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ Eastern and northern Australia told to prepare for wet summer as La Niña develops for the second year in a row by Jack Mahony from Sky News. November 23, 2021,

- ^ Sydney rain smashes summer records as cleanup from deluge continues By Raffaella Ciccarelli from 9news. February 24, 2022.

- ^ Queensland's wet weather continues with more than 400mm of rain falling in three hours, flood warnings issued ABC News Australia. 25 February 2022.

- ^ The wild ways of La Niña As storms batters, the east coast, is this what our future looks like? by Cosmos. 25 February 2022

- ^ Six dead, thousands in Ipswich and Brisbane on alert as wild weather continues to lash Queensland By Ashleigh McMillan and Stuart Layt from The Sydney Morning Herald. February 27, 2022.

- ^ La Niña, 3 years in a row: a climate scientist on what flood-weary Australians can expect this summer By Andrew King from The Conversation. September 13, 2022.

- ^ How La Niña could wipe out stretches of Australia's beaches and dunes with wild weather ABC News. October 8 2022.

- ^ La Niña’s three-year reign across Australia finally ends, promising drier, hotter weather by ABC News Australia. Tom Saunders. 10 March 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ World Meteorological Organization declares onset of El Niño conditions by WMO. 4 July 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology formally declares El Niño weather event, as hot and dry conditions sweep south-east Australia By Tom Williams and Brianna Morris-Grant from ABC News. 19 September 2023.

External links[edit]

- ENSO Outlook an alert system for the El Niño–Southern Oscillation by BOM

- El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) by BOM