Elizabeth Cotten

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Elizabeth Cotten | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Elizabeth Nevills |

| Born | January 5, 1893 Carrboro, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | June 29, 1987 (aged 94) Syracuse, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Labels | |

Elizabeth "Libba" Cotten (née Nevills; January 5, 1893 – June 29, 1987)[1][2][3] was an influential American folk and blues musician. She was a self-taught left-handed guitarist who played a guitar strung for a right-handed player, but played it upside down.[4] This position meant that she would play the bass lines with her fingers and the melody with her thumb. Her signature alternating bass style has become known as "Cotten picking".[5] NPR stated "her influence has reverberated through the generations, permeating every genre of music."[6]

Her album Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar (1958), was placed into the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress, and was deemed as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". The album included her signature recording "Freight Train", a song she wrote in her early teens.[7] In 1984, her live album Elizabeth Cotten Live!, won her a Grammy Award for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording, at the age of 90.[8] That same year, Cotten was recognized as a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment for the Arts.[9] In 2022, she was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as an early influence.[10]

Early life[edit]

Cotten was born in 1893[11] to a musical family near Chapel Hill, North Carolina,[11] in an area that would later be incorporated as Carrboro. Her parents were George Nevill (also spelled Nevills) and Louisa (or Louise) Price Nevill. Elizabeth was the youngest of five children. She named herself on her first day of school, when the teacher asked her name, because at home she was only called "Li'l Sis".[12] By the age of eight, she was playing songs. At age nine, she was forced to quit school and began work as a domestic worker.[13] At the age of twelve, she had a live-in job at Chapel Hill. She earned a dollar a month, that her mother saved up to buy her first guitar.[14][15] The guitar, a Sears and Roebuck brand instrument, cost $3.75 (equivalent to $127 in 2023).[14] Although self-taught, she became proficient at playing the instrument,[16] and her repertoire included a large number of rags and dance tunes.[13]

By her early teens, she was writing her own songs, one of which, "Freight Train", became one of her most recognized.[17] She wrote the song in remembrance of a nearby train that she could hear from her childhood home.[13] The 1956 UK recording of the song by Chas McDevitt and Nancy Whiskey was a major hit and is credited as one of the main influences on the rise of skiffle in the UK.[18]

Around the age of 13, Cotten began working as a maid along with her mother. On November 7, 1910, at the age of 17, she married Frank Cotten.[19] The couple had a daughter, Lillie, and soon after Elizabeth gave up guitar playing for family and church. Elizabeth, Frank and their daughter Lillie moved around the eastern United States for a number of years, between North Carolina, New York City, and Washington, D.C., finally settling in the D.C. area. When Lillie married, Elizabeth divorced Frank and moved in with her daughter and her family.

Rediscovery[edit]

Cotten retired from playing the guitar for 25 years, except for occasional church performances. She did not begin performing publicly and recording until she was in her 60s. She was discovered by the folk-singing Seeger family while she was working for them as a housekeeper.

While working briefly in a department store, Cotten helped a child wandering through the aisles find her mother. The child was Peggy Seeger, and the mother was the composer Ruth Crawford Seeger. Soon after this, Cotten again began working as a maid, this time for Ruth Crawford Seeger and Charles Seeger, and caring for their children, Mike, Peggy, Barbara, and Penny. The Seeger family kids, who were too young to pronounce "Elizabeth", began calling her "Libba", and she embraced that nickname later in life.[20] While working with the Seegers (a voraciously musical family that included Pete Seeger, a son of Charles from a previous marriage), she remembered her own guitar playing from 40 years prior and picked up the instrument again and relearned to play it, almost from scratch.[14]

Later career and recordings[edit]

In the later half of the 1950s, Mike Seeger began making bedroom reel-to-reel recordings of Cotten's songs in her house.[21] These recordings later became the album Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar, which was released by Folkways Records. Since the release of that album, her songs, especially her signature song, "Freight Train" — which she wrote when she was a teenager — have been covered by Peter, Paul, and Mary, Jerry Garcia, Bob Dylan, Joe Dassin, Joan Baez, Devendra Banhart, Laura Gibson, Laura Veirs, His Name Is Alive, Doc Watson, Taj Mahal, Geoff Farina, Esther Ofarim and Country Teasers.[17][20]

Peggy Seeger took the song "Freight Train" with her to England, where it became popular in folk music circles. British songwriters Paul James and Fred Williams subsequently misappropriated it as their own composition and copyrighted it. Under their credit, it was then recorded by British skiffle singer Chas McDevitt, who recorded the song in December 1956. Under advice from his manager (Bill Varley), McDevitt then brought in folk-singer Nancy Whiskey and re-recorded the song with her doing the vocal; the result was a chart hit. McDevitt's version influenced many young skiffle groups of the day, including The Quarrymen. Under the advocacy of the influential Seeger family, the copyright was eventually restored to Cotten.[22][23] Nevertheless, it remains mis-credited in many sources.

Shortly after that first album, she began playing concerts with Mike Seeger, the first of which was in 1960 at Swarthmore College.

In the early 1960s, Cotten went on to play concerts with some of the big names in the burgeoning folk revival. Some of these included Mississippi John Hurt, John Lee Hooker, and Muddy Waters at venues such as the Newport Folk Festival and the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife.

The newfound interest in her work inspired her to write more songs to perform, and in 1967 she released a record created with her grandchildren, which took its name from one of her songs, "Shake Sugaree". The song featured 12-year-old Brenda Joyce Evans, Cotten's great-grandchild, and future Undisputed Truth singer.[citation needed]

Using profits from her touring, record releases and awards given to her for her own contributions to the folk arts, Cotten was able to move with her daughter and grandchildren from Washington, D.C., and buy a house in Syracuse, New York. She was also able to continue touring and releasing records well into her 80s. In 1984, she won the Grammy Award for Best Ethnic or Traditional Recording, for the album Elizabeth Cotten Live, released by Arhoolie Records. When accepting the award in Los Angeles, her comment was, "Thank you. I only wish I had my guitar so I could play a song for you all." In 1989, Cotten was one of 75 influential African-American women included in the photo documentary I Dream a World.[citation needed]

Cotten died in June 1987, at Crouse-Irving Hospital in Syracuse, New York, at the age of 94.[25]

Guitar style[edit]

Cotten began writing music while toying with her older brother's banjo. She was left-handed, so she played the banjo in reverse position. Later, when she transferred her songs to the guitar, she formed a unique style, since on a 5-string banjo the uppermost string is not a bass string, but a short, high-pitched string which ends at the fifth fret. This required her to adopt a unique style for the guitar. She first played with the "all finger down strokes" like a banjo.[14] Later, her playing evolved into a unique style of fingerpicking. Her signature alternating bass style is now known as "Cotten picking". Her fingerpicking techniques have influenced many other musicians.[26]

Discography[edit]

LPs[edit]

- Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar (1958)

- Vol. 2: Shake Sugaree (1967)

- Vol. 3: When I'm Gone (1979)

Recordings on CD[edit]

- Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes (also known as Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar) (1958)

- Shake Sugaree

- Live!

- Vol. 3: When I'm Gone

Special collections[edit]

- Mike Seeger Collection (#20009), Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Filmography[edit]

Video and DVD[edit]

- Masters of the Country Blues: Elizabeth Cotten and Jesse Fuller (1960)

- Me and Stella: A Film about Elizabeth Cotten (1976)

- Elizabeth Cotten Portrait Collection (1977–1985)

- Homemade American Music (1980)

- Libba Cotten: An Interview and Presentation Ceremony (1985)

- Elizabeth Cotten with Mike Seeger (1994)

- Legends of Traditional Fingerstyle Guitar (1994)

- Mike Seeger and Elizabeth Cotten (1991)

- Jesse Fuller and Elizabeth Cotten (1992)

- The Downhome Blues (1994)

- John Fahey, Elizabeth Cotten: Rare Performances and Interviews (1969 & 1994)

- Rainbow Quest with Pete Seeger. Judy Collins and Elizabeth Cotten (2005)

- Elizabeth Cotten in Concert, 1969, 1978, and 1980 (1969 & 2003)

- The Guitar of Elizabeth Cotten (2002)

Awards and honors[edit]

- In 1980, 1982, and 1987, Cotten was nominated for a Blues Music Award in the Traditional Blues Female Artist category.[27]

- Cotten was a recipient of a 1984 National Heritage Fellowship awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which is the United States government's highest honor in the folk and traditional arts.[28]

- In 1985, she won the Grammy Award in the Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording category for Elizabeth Cotten Live![29]

- In 1986, she was nominated for a Grammy Award in the Best Traditional Folk Recording category for her 20th Anniversary Concert album.[29]

- In 2022, Cotten was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the Early Influence category.[17][30]

- In 2023, Cotten was named 36th best guitarist of all time by Rolling Stone.[31]

Further reading[edit]

- Bastin, Bruce (1986). Red River Blues. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Cohen, John; Marcus, Greil (2001). There Is No Eye: John Cohen Photographs. New York: PowerHouse Books.

- Cohn, Lawrence (1993). Nothing but the Blues: The Music and the Musicians. New York: Abbeville Press.

- Conway, Cecilia (1995). African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- Escamilla, Brian (1996). Contemporary Musicians: Profiles of the People in Music. Vol. 16.

- Harris, Sheldon (1979). Blues Who's Who. New York: Da Capa Press.

- Hood, Phil (1986). Artists of American Folk Music: The Legends of Traditional Folk, the Stars of the Sixties, the Virtuosi of New Acoustic Music. New York: Quill.

- Menconi, David (2020). Step it Up and Go. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-5935-0.

- Santelli, Robert (2001). American Roots Music. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Seeger, Mike. Liner notes accompanying Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes, by Elizabeth Cotten. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Folkways, 1989 reissue of the 1958 album Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar.

- Smith, Jessie Carney (1993). Epic Lives: One Hundred Black Women Who Made a Difference. Detroit: Visible Ink Press.

- Smith, Jesse Carney, ed. (1992). Notable Black American Women. Detroit: Gale Research.

- Veirs, Laura (January 16, 2018). Libba. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-4857-1.

- Wenberg, Michael (2002). Elizabeth's Song. (Children's book.) Hillsboro, Oregon: Beyond Words Publishing.

References[edit]

- ^ Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. p. 278. ISBN 978-0313344237.

- ^ "Happy Birthday Libba Cotten!". ncarts.org. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "Remembering Elizabeth Cotten by L. L. Demerle'". eclectica.org. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2009). "Cotten Elizabeth 'Libba'". Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531373-4.

- ^ Zollo, Rick (2006). "Cotten Picking: Elizabeth Cotten and the Folk Revival". Shenandoah. 56 (2): 67–75.

- ^ "How Elizabeth Cotten's music fueled the folk revival". NPR.

- ^ "Elizabeth Cotten: musician who kickstarted the folk revival". faroutmagazine.co.uk. May 14, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ "Elizabeth Cotten: Master of American folk music". Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ "Elizabeth Cotten". www.arts.gov. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ "Elizabeth Cotten | Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". www.rockhall.com. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Federal Census, Chapel Hill. 1870, 1880, 1900.

- ^ Summers, Barbara, ed. (1989). I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America. photographs and interviews by Brian Lanker. New York: Stewart, Tabori, & Chang. p. 156. ISBN 155670092X. OCLC 18745605.

- ^ a b c Govenar, Alan, ed. (2001). "Elizabeth Cotten: African American Songster and Songwriter". Masters of Traditional Arts: A Biographical Dictionary. Vol. 1 (A-J). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio. pp. 144–146. ISBN 1576072401. OCLC 47644303.

- ^ a b c d Bailey, Brooke (1994). The Remarkable Lives of 100 Women Artists. Bob Adams. pp. 32. ISBN 1-55850-360-9.

- ^ "Elizabeth Cotten – Masters of Traditional Arts". mastersoftraditionalarts.org. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Demerle', L. L. (1996). "Remembering Elizabeth Cotten". Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Herbert, Geoff (May 4, 2022). "Syracuse folk legend Libba Cotten to be inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". The Post-Standard. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Ridin' the Freight Train with Chas McDevitt". January 24, 2003. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2002.

- ^ Orange County Register of Deeds Office, Marriage License Book 10, p. 268.

- ^ a b Struck, Jules (May 5, 2022). "A star after 60: Syracuse's Elizabeth 'Libba' Cotten taught Jerry Garcia, Pete Seeger the meaning of folk music". The Post-Standard. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Mike Seeger Collection Inventory (#20009), Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

- ^ ""Elisabeth Cotten"". Biography.yourdictionary.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ ""Chas McDevitt"". AllMusic. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

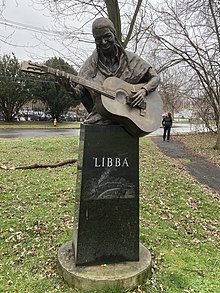

- ^ Nolan, Maureen (February 21, 2010). "Libba's legacy: Musician Elizabeth Cotten to be honored with statue". The Post-Standard. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Elizabeth (Libba) Cotten, 95, a Blues and Folk Songwriter". New York Times. June 30, 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Jones, Josh (May 1, 2019). "Elizabeth Cotten Wrote "Freight Train" at 11, Won a Grammy at 90, and Changed American Music In-Between". Open Culture. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Award Winners and Nominees [search]". blues.org. The Blues Foundation. 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ "NEA National Heritage Fellowships 1984". arts.gov. National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "Artist: Elizabeth Cotten". grammy.com. Recording Academy. 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ "Artist: Elizabeth Cotten:Early Influence Award". www.wkyc.com. 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ "The 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

External links[edit]

- Elizabeth Cotten

- Elizabeth Cotten at AllMusic

- Elizabeth Cotten discography at Discogs

- Cotten discography at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

- "Interview with Blues and Folk Singer Elizabeth Cotten" for the WGBH series Say Brother

- Clip of Cotten performing in 1969

- Elizabeth Cotten

- Elizabeth Cotten Freight Train

- North Carolina Highway Marker for Elizabeth Cotten Archived January 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine