Elsa Dorfman

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Elsa B. Dorfman | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait of Elsa B. Dorfman in her studio | |

| Born | April 26, 1937 Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 30, 2020 (aged 83) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Tufts University (BA) Boston College (MEd) |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse | |

Elsa B. Dorfman (April 26, 1937 – May 30, 2020) was an American portrait photographer. She worked in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and was known for her use of a large-format instant Polaroid camera.[1]

Early life and education[edit]

Dorfman was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on April 26, 1937, and was raised in Roxbury and Newton.[2][3] She was the eldest of three daughters of Arthur and Elaine (Kovitz). Her father worked at a grocery chain as a produce buyer; her mother was a housewife.[2] Her family was of Jewish descent.[4] She studied at Tufts University, where she majored in French literature. During her junior year, she went on exchange to Europe, where she worked in Brussels for Expo 58 and lived in Paris, living in the same student accommodation as Susan Sontag.[2] Dorfman graduated in 1959 and subsequently moved to New York City, where she was employed as a secretary by Grove Press,[2] a leading Beat publisher.[5] When she returned to Boston, she pursued a master's degree in elementary education at Boston College.[6]

Career[edit]

After earning her master's degree, Dorfman spent a year teaching fifth grade at a school in Concord.[2]

Calling herself the "Paterson Society", Dorfman began arranging readings for many Beat authors who had become friends, maintaining an active correspondence with them as they traveled the world. In 1963, she began working for the Educational Development Corporation whose photographer, George Cope, introduced her to photography in June 1965. She made her first sale two months later, in August 1965, for $25 of a photograph of Charles Olson which was used on the cover of his book The Human Universe. Due to economic limitations, she did not buy her own camera until 1967, when she sent a check for $150 to Philip Whalen who was then in Kyoto, Japan, and he in turn enlisted Gary Snyder, who could speak Japanese, to purchase the camera and mail it to her.[7] In May 1968, she moved into the Flagg Street house which would become the basis of her Housebook.[8][9]

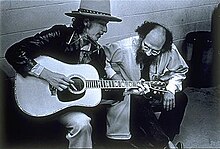

Dorfman's principal published work, originally published in 1974, was Elsa's Housebook – A Woman's Photojournal,[10] a photographic record of family and friends who visited her in Cambridge when she lived there during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Many well known people, especially literary figures associated with the Beat generation, are prominent in the book, including Lawrence Ferlinghetti,[11] Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Gary Snyder, Gregory Corso, and Robert Creeley,[12][13] in addition to people who would become notable in other fields, such as radical feminist Andrea Dworkin,[11] and civil rights lawyer Harvey Silverglate (who would become Dorfman's husband).[2] She also photographed staples of the Boston rock scene such as Jonathan Richman,[13] frontman of The Modern Lovers, and Steven Tyler of Aerosmith.[11]

In 1995, she collaborated with graphic artist Marc A. Sawyer to illustrate the booklet 40 Ways to Fight the Fight Against AIDS. She photographed people, both with and without AIDS, each engaged in one of forty activities that might help AIDS victims in their daily life. The photographs were exhibited 1995 at the Lotus Development Corporation in Cambridge, in Provincetown and New York City. The artist donated the costs of producing the photographs for this project.[14]

Dorfman co-starred in the documentary No Hair Day (1999).[2]

She was known for her use of the Polaroid 20 by 24 inch camera (one of only six in existence),[15] from which she created large prints. She photographed famous writers, poets, and musicians including Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg.[16][17] Due to bankruptcy, the Polaroid Corporation entirely ceased production of its unique instant film products in 2008. Dorfman stocked up with a year's supply of her camera's last available 20 by 24 instant film.[1]

Dorfman's life and work were the subject of the 2016 documentary film The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman's Portrait Photography, directed by Errol Morris.[18]

Her portraits are held in the collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Harvard Art Museums, the Portland Museum of Art in Maine and others.[6]

Personal life[edit]

In 1967, Dorfman met Harvey Silverglate, who was representing the defense in a drug trial. Dorfman thought the case could be the subject of a book and talked it over with him, after which Silverglate asked to take a portrait of him and his brother to give to their mother. They married nearly a decade later in 1976.[2] Together, they had one son, Isaac.[13]

Dorfman died on May 30, 2020, at her home in Cambridge. She was 83 according to her husband and she suffered kidney failure.[2][3]

Works[edit]

- Gail Mazur and Gordon Cairnie at Grolier

References[edit]

- ^ a b Mark Feeney (March 16, 2008). "Instant karma". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Feeney, Mark (May 30, 2020). "Elsa Dorfman, photographer whose distinctive portraits illuminated her subjects and herself, dies at 83". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Becker, Deborah (May 30, 2020). "Cambridge Photographer Elsa Dorfman, Famous For Her Giant Polaroids, Dies At 83". WBUR-FM. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Means, Sean P. (July 13, 2017). "Cheery 'B-Side' marks end of a photographer's era". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Dorfman explains her background in her Housebook The Camera. Archived September 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Sharma, Hena. "American portrait innovator Elsa Dorfman has died at age 83". CNN. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Elsa Dorfman (May 19, 2016). "An Interview With Elsa Dorfman". Digital Photo Pro (Interview). Interviewed by Mark Edward Harris. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Elsa Dorfman discusses Elsa's Housebook: A Woman's Photojournal". Harvard Book Store. October 25, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Dorfman, Elsa (1974). Elsa's Housebook: A Woman's Photojournal. D. R. Godine. p. 14. ISBN 9780879230999.

- ^ Elsa Dorfman's Housebook. Archived August 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c "Cultural Visionary: Elsa Dorfman". Cambridge Community Foundation. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Shanahan, Mark; Goldstein, Meredith (October 27, 2012). "Elsa Dorfman talks about 'Housebook'". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c Whyte, Murray (February 6, 2020). "Elsa Dorfman looks back at 50 years on both sides of the camera". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Hoffmann, K. (1999). Elsa Dorfman: Portraits of Our Time. Woman's Art Journal Vol. 20, No. 2, 1999, 28.

- ^ According to her web site FAQ, Frequently Asked Questions about Elsa Dorfman's Portrait Photography on the Polaroid 20x24 Camera. Archived April 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Allen Ginsberg on Flagg Street, 1973 at the Jewish Museum (New York)". Thejewishmuseum.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Indrisek, Scott (June 27, 2017). "The Polaroid Pioneer Who Shot Allen Ginsberg Naked Wants to Take Your Portrait". Artsey.net. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Barker (September 13, 2016). "Film Review: 'The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman's Portrait Photography'". Variety. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

Archives and records[edit]

- Elsa Dorfman Collection of Polaroid cameras and film at Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Elsa Dorfman photographs, 1957–1970, University Archives and Special Collections, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston

- Finding aid to Elsa Dorfman papers, 1960–1969, at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Elsa Dorfman at IMDb

- Elsa Solo on Vimeo by John Reuter