Energy efficiency in British housing

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article needs to be updated. (August 2016) |

Domestic housing in the United Kingdom presents a possible opportunity for achieving the 20% overall cut in UK greenhouse gas emissions targeted by the Government for 2010. However, the process of achieving that drop is proving problematic given the very wide range of age and condition of the UK housing stock.

Carbon emissions[edit]

Although carbon emissions from housing have remained fairly stable since 1990 (due to the increase in household energy use having been compensated for by the 'dash for gas'), housing accounted for around 30% of all the UK's carbon dioxide emissions in 2004 (40 million tonnes of carbon)[1] up from 26.42% in 1990 as a proportion of the UK's total emissions.[2] The Select Committee on Environmental Audit noted that emissions from housing could constitute over 55% of the UK's target for carbon emissions in 2050.[1]

A 2006 report commissioned by British Gas[3] estimated the average carbon emissions for housing in each of the local authorities in Great Britain, the first time that this had been done. This indicated that housing in Uttlesford (Essex) produced the highest emissions (8,092 kg of carbon dioxide per dwelling). This was 250% higher than housing in Camden (London) which produced the least (averaging 3,255 kg). Among the 23 towns included, Reading had the highest emissions (6,189 kg), with Hull the lowest (4,395 kg). The variations are due to a number of factors, including the age, size and type of the housing stock, together with the efficiency of heating systems, the mix of fuels used, the ownership of appliances, occupancy levels and the habits of the occupants.

Zero carbon ambition[edit]

In the December 2006 Pre-Budget Report,[4] the Government announced their 'ambition' that all new homes will be 'zero-carbon' by 2016 (i.e. built to zero-carbon building standards). To encourage this, an exemption from Stamp duty land tax was to be granted, lasting until 2012, for all new zero-carbon homes up to £500,000 in value.[5]

Whilst some organisations applauded the initial announcement of the scheme, in the pre-budget statement from the then UK Chancellor, Gordon Brown, others are concerned about the government's ability to deliver on the promise.[6][7]

Domestic energy use[edit]

In 2003 the housing stock in the United Kingdom was amongst the least energy efficient in Europe.[8] In 2004, housing (including space heating, hot water, lighting, cooking, and appliances) accounted for 30.23% of all energy use in the UK (up from 27.70% in 1990).[9] The figure for London is higher at approximately 37%.[10]

In view of the progressive tightening of the Building Regulations' requirements for energy efficiency since the 1970s (see the history section below), it might be expected that a significant cut in domestic energy use would have occurred, however this has not yet been the case.

Although insulation standards have been increasing, so has the standard of home heating. In 1970, only 31% of homes had central heating. By 2003 it had been installed in 92% of British homes,[11] leading in turn to a rise in the average temperature within them (from 12.1 °C to 18.20 °C).[12] Even in homes with central heating, average temperatures rose 4.55 °C during this period.

At the same time, the increase in the number of households, increasing numbers of domestic electrical appliances, an increase in the number of light fittings, reduction in the average number of occupants per household, plus other factors, had led to an increase in total national domestic energy consumption from around 25% in 1970 to about 30% in 2001, and remained on an upward trend (BRE figures).

The figures for energy consumed by end use for 2003.[13]

- Space heating - 60.51% (57.61% in 1990)

- Water heating - 23.60% (25.23% in 1990)

- Appliances and lighting - 13.15% (13.4% in 1990)

- Cooking - 2.74% (3.76%)

The Green Deal[edit]

The Green Deal provided low interest loans for energy efficiency improvements to the energy bills of the properties the upgrades are performed on.[14] These debts are passed onto new occupiers when they take over the payment of energy bills. The costs of the loan repayments should be less than the savings on the bills from the upgrades, however this will be a guideline and not legally enforceable guarantee. It is believed that tying repayment to energy bills will give investors a secure return. The Green Deal for the domestic property market was launched in October 2012. The Commercial Green Deal was launched in January 2012 and released in a series of stages to help with the varying needs and requirements of commercial properties.

Building regulations[edit]

The 1965 Building Regulations [15] introduced the first limits on the amount of energy that could be lost through certain elements of the fabric of new houses. This thermal performance was expressed in the imperial units of the time (the amount of heat in BTU lost per square foot, for each degree Fahrenheit of temperature difference between inside and outside). The 1965 regulations were the first set of truly nationwide standards, prior to this local authorities set their own local regimes. Part F of the 1965 regulations defines minimum thermal performance, and schedule 11 of the same document gives examples of compliant methods for builders and architects to refer to. While novel at the time, by modern standards these limits set quite a low target, unfilled cavity walls, 2 inches of loft insulation and uninsulated concrete floors were deemed adequate for the reference standards. The 1972 regulations [16] retained the same standards but converted to metric units (mm) and the modern u-value (the amount of heat lost per square metre, for each degree Celsius of temperature difference between inside and outside).

In effect, the Target Insulation was u-values of 1.42 W/m2·K for the roof and floor and 1.7 W/m2·K for external walls. Modern performance standards require values less than 20% of this. This u-value approach is slightly regressive in that richer people live in bigger houses which tend to have a lower ratio of surface area to floor area, although they are often detached, which can offset the advantage over smaller row houses.

These first limits were tightened following the 1973 oil crisis, and on several subsequent occasions, including the addition of limits for doors and windows in the year 2000 that effectively required double glazing for the first time. (see below). Despite this, UK insulation levels have been introduced later or remained lower compared to the EU average.[17]

Changes in 2006[edit]

The energy policy of the United Kingdom through the 2003 Energy White Paper[18] articulated directions for more energy efficient building construction. Hence, the year 2006 saw a significant tightening of energy efficiency requirements within the Building Regulations (for earlier regulations, see separate section below).

With the long-term aim of cutting overall emissions by 60% by 2050, and by 80% by 2100, the intention of the 2006 changes was to cut energy use in new housing by 20% compared to a similar building constructed to the 2002 standards. The changes were the first to the regulations brought about by the desire to reduce emissions, though some have raised doubts about whether they will actually achieve the 20% cut (see criticisms section).

In the 2006 regulations, the u-value was replaced as the primary measure of energy efficiency by the Dwelling Carbon Dioxide Emission Rate (DER),[19] an estimate of carbon dioxide emissions per m2 of floor area. This is calculated using the Government's Standard Assessment Procedure for Energy Rating of Dwellings (SAP 2005).[20]

In addition to the levels of insulation provide by the structure of the building, the DER also takes into account the airtightness of the building, the efficiency of space and water heating, the efficiency of lighting, and any savings from solar power or other energy generation technologies employed, and other factors. For the first time, it also became compulsory to upgrade the energy efficiency in existing houses when extensions or certain other works are carried out.

Some organisations have raised doubts over the claim that the changes will result in a 20% saving. Issues cited have included alleged problems with the calculation methods, the limitations of the modelling software, and the specification of the reference building used in the model.[21] For example, a 2005 study sponsored by the Pilkington Energy Efficiency Trust[22] indicated that the savings would only be in the region of 9%.[23]

There are also concerns about enforcement, with a Building Research Establishment study in 2004 indicating that 60% of new homes do not conform to existing regulations.[24] A 2006 survey for the Energy Saving Trust revealed that Building Control Officers considered energy efficiency 'a low priority' and that few would take any action over failure to comply with the Building Regulations because the matter 'seemed trivial'.[25][26]

Further changes[edit]

In December 2006, the government announced their ambition that all new housing should be built to zero-carbon standards from 2016;[27] i.e., that the carbon emitted during a typical year should be balanced by renewable energy generation. Despite being the first country in the world to adopt such a policy[28] the initiative was generally welcomed by the industry in principle,[29] despite some subsequent concern over the practicalities.[30][31]

On 1 April 2011 the WWF resigned from the taskforce on Zero-Carbon homes,[32] stating that 'the zero-carbon policy is now in tatters' after the Government unilaterally decided to change the scope of the 'zero carbon' policy to exclude some emissions[33] not currently covered by the building regulations. The UK Green Building Council estimated that the change, published at the time of the March 2011 budget, will result in only two-thirds of the emissions of a new home being mitigated.[34]

In 2004, the Government indicated that the next revision to the energy performance standards of the Building Regulations would be in 2010.[35] In the consultation document Building a Greener Future: Towards Zero Carbon Development it was proposed that the 2010 revision should require a further 25% improvement in the energy/carbon performance, in line with the 2004 proposals.[36] It was further envisaged that there would be a 44% improvement in 2013, compared to 2006 levels. This would then be followed by the adoption of a zero carbon requirement in 2016, applied to all home energy use including appliances.[36] These steps in performance would align the energy efficiency requirement of the Building Regulations with those of Levels 3, 4 and 6 of the Code for Sustainable Homes in 2010, 2013 and 2016 respectively.[37]

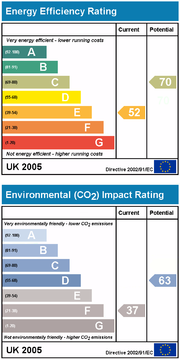

Home energy labelling[edit]

Originally, from June 2007, all homes (and other buildings) in the UK would have to undergo Energy Performance Certification (also commonly known as an EPC Certificate) before they are sold or let,[38] in order to meet the requirements of the European Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (Directive 2002/91/EC).[39] The scheme provides the owner or landlord with an 'energy label' so that they can demonstrate the energy efficiency of the property, and is also included in the new Home Information Packs. The scheme has been criticized for its methodology and superficial approach, especially for old buildings. For example, it ignores thick walls with their low heat transmission, and its recommendations for compact fluorescent lamps, which can damage sensitive textiles and paintings.

It is hoped that energy labelling will raise awareness of energy efficiency, and encourage upgrading to make properties more marketable. Incentives may be available for carrying out energy conservation measures.[40] Research by comparethemarket.com showed homes across the UK were worth more when scored highly in an EPC.[41][42]

For new building, SAP calculations are to form the basis for the certification, while RDSAP (Reduced Data SAP) will be used to assess existing properties. It is estimated that only 10% of the nation's housing will score above 60 on the scale, although most will score above 40.[43]

Other rating schemes[edit]

Another rating scheme of note is the Government sponsored EcoHomes rating, mostly used in public sector housing, and only applicable to new properties or major refurbishments. This actually measures a range of sustainability issues, of which energy efficiency is only one. EcoHomes is to be replaced by the Government's Code for Sustainable Homes in 2007.

The Energy Saving Trust set requirements for 'good practice' and 'advanced practice' for achieving lower energy buildings,[44] while the Association for Environment Conscious Building's CarbonLite programme specifies Silver and Gold standards, the latter approaching a zero energy building.

In Wales where 'zero-carbon homes' are the aspiration for 2011 (although 2012 is more likely) the requirements are for Code for Sustainable Homes or equivalent. This has opened the doors for standards like Passiv Haus and the CarbonLite programme. Another lesser known building type that does not rely on airtightness in order to get its energy rating is Bio-Solar-Haus. This is not a well known type of house, but it has a range of positive advantages like it is built out of renewable resources and it is a breathable structure thus making it much healthier to live in.

Grants[edit]

The Government's low carbon buildings programme was launched in 2006 to replace the earlier Clear Skies and Solar PV programmes. It offers grants towards the costs of solar thermal heating, small wind turbine, micro hydro, ground source heat pump, and biomass installations. As of January 2007 funding for grants is proving insufficient to meet demand.[45]

A similar scheme, the Scottish Community and Household Renewables Initiative operates in Scotland, which also offers grants towards the cost of air source heat pumps.

Local government[edit]

Under the Home Energy Conservation Act 1995, local authorities are required to consider measures to improve the energy efficiency of all residential accommodation in their areas, although they are not required to implement any measures. Most local authorities provide free advice on energy conservation and some also provide home visits, often targeting those in social housing and the fuel poor. Some also demand minimum levels of energy efficiency in newly constructed buildings. It was expected that the Act would result in a 30% cut in energy usage between 1996 and 2010. An overall cumulative improvement of 14.7% was reported to DEFRA for the year ending March 2004, but a large part of this would have happened without HECA.[46]

In the South,[citation needed] most local authority housing was sold off in the 1980s-90s under RTB (Right to buy scheme), so the remaining stock is small. Much social housing has also been transferred to housing associations.

Demonstration and pioneering projects[edit]

One of the most important energy efficiency demonstration projects was the 1986 Energy World exhibition in Milton Keynes, which attracted international interest. Fifty-one houses were built, designed to be at least 30% more efficient than the Building Regulations then in force. This was calculated using the Milton Keynes Energy Cost Index (MKECI), a test-bed for the subsequent SAP rating system and the National Home Energy Rating scheme. Energy World was preceded by the earlier Salford low-energy houses, built in the early 1980s, which continue to be 40% more efficient than the 2010 Building Regulations.[47]

The Beddington Zero Energy Development (BedZED), a non-traditional housing scheme of 82 dwellings near Beddington, London included zero fossil energy usage as one of its key design features. The project was completed in 2002 and is the UK's largest eco-development. As designed, the energy used is generated from renewables on site. In use, BedZED has yielded considerable useful feedback, not least that energy efficiency and passive design features delivery more reliable reduced carbon emissions than active systems. Due to their superinsulation, the properties use 88% less energy (measured) for space heating compared to those built to the 2002 Building Regulations, while the reduction for water heating is 57%. Measured electrical use for cooking, appliances and occupant's plug loads ('unregulated energy' consumption) are some 55% lower than UK norms (bedzed-seven-years-on).[48]

The Green Building in Manchester City Centre and has been built to high energy efficiency standards and won a 2006 Civic Trust Award for its sustainable design.[49] The cylindrical shape of the ten-storey tower provides the smallest surface area related to the volume, ensuring less energy is lost through thermal dissipation. Other technologies including solar water heating, a wind turbine and triple glazing.

The South Yorkshire Energy Centre at Heeley City Farm in Sheffield is an example of refurbishing an existing property to show the options available.[50]

The EcoHouse in Leicester[51] is to be renovated in 2011 to provide a demonstration of Retrofit for the Future energy efficiency standards.[52]

The Old Home SuperHome initiative features many owner occupied, existing home retrofits which achieve a 60% carbon saving which can be visited by the public.[53] Many of the homes have dramatically improved their energy efficiency to achieve these carbon savings, while some have also installed renewable energy technologies.

International comparisons[edit]

International comparisons of particular note include:

- The 1977 Danish BR77 standard (the first to set demanding energy efficiency requirements).

- The SBN-80 (Svensk Bygg Norm) 1980 Swedish Building Standards, which in 1983 was in advance of the UK 2002 standards.[54]

- The voluntary Canadian R-2000 standard, to which around 14,000 houses had been built in the 10 years to 1992.[55]

Since then many more have been built in Canada, in Japan, and in various other countries including a number in the UK. Currently energy savings of 30% to 40% are typically achieved in Canada.[56]

- The voluntary German Passivhaus standard. Properties built to the standards use approximately 85% less energy and produce 95% less carbon dioxide compared to properties built to the UK's 2002 standards. Over 6,000 such houses have been built across several European countries.[57]

- The voluntary Swiss Minergie standard which requires that general energy consumption must not to be higher than 75% of that of average buildings and that fossil-fuel consumption must not be higher than 50% of the consumption of such buildings, and the Minergie-P standard, requiring virtually zero energy consumption.

Research[edit]

In 2005, the Select Committee on Environmental Audit expressed their concern that there was a lack of significant funding for research and development of sustainable construction methods,[58] with funding for the Building Research Establishment having been "drastically" cut in the previous 4 years. As a result, many of the sustainable building materials used in the UK are imported from Germany, Switzerland and Austria—some of the countries that have been prominent in research.

Existing housing stock[edit]

Even if all new housing does become zero carbon by 2016, the energy efficiency of the remainder of the housing stock would need to be addressed.

The 2006 Review of the Sustainability of Existing Buildings revealed that 6.1 million homes lacked an adequate thickness of loft insulation, 8.5 million homes had uninsulated cavity walls, and that there is a potential to insulate 7.5 million homes that have solid external walls. These three measures alone have the potential to save 8.5 million tonnes of carbon emissions each year. Despite this, 95% of homeowners think that the heating of their own home is currently effective.[59]

See UK Government policy for improving home energy efficiency for further information on policies from 1945 to 2016 and their effectiveness.

Historic building regulations energy efficiency requirements[edit]

| Year | Minimum depth |

|---|---|

| 1965 | 25 mm |

| 1975 | 60 mm |

| 1985 | 100 mm |

| 1990 | 150 mm |

| 1995 | 200 mm |

| 2002 | 250 mm |

| 2003 | 270 mm |

The u-value limits introduced in 1965 were:[61]

- 1.7 for walls

- 1.4 for roofs

Following the 1973 oil crisis, these were tightened in 1976 to:[62]

- 1.0 for exposed walls, floors and non-solid ground and exposed floors

- 1.7 for semi-exposed walls

- 1.8 average for walls and windows combined

- 0.6 for roofs

1985 saw the second tightening of these limits, to:

- 0.6 for exposed walls, floors and ground floors

- 1.0 for semi-exposed walls

- 0.35 for roofs

These limits were reduced again in 1990:

- 0.45 for exposed walls, floors and ground floors

- 0.6 for semi-exposed walls

- 0.25 for roofs

- plus a requirement that the area of windows should not be more than 15% of the floor area.

Like the 2006 changes, it was predicted that the introduction of these limits would result in a 20% reduction in energy use for heating. A survey by Liverpool John Moores University predicted that the actual figure would be 6% (Johnson, JA "Building Regulations Research Project").

In the 1995 Building Regulations, insulation standards were cut to the following U-values:

- 0.45 for exposed walls, floors and ground floors

- 0.6 for semi-exposed walls and floors

- 0.25 for roofs

- the limit on window area was raised to 22.5%

The 2002 regulations reduced the U-values, and made additional elements of the building fabric subject to control. Although there was in practice considerable flexibility and the ability to 'trade off' reductions in one area for increases in another, the 'target' limits became:

- 0.35 for walls

- 0.25 for floors

- 0.20 or 0.25 for pitched roofs (depending on the construction)

- 0.16 for flat roofs

- 2.2 for metal framed doors and windows

- 2.0 for other doors and windows

- the limit on window area was raised again to 25%

Similar limits were introduced into Scotland in 2002 & 2006, though with a lower limit of 0.3 or 0.27 for walls, and some other variations.

It was claimed by Government that these measures should cut the heating requirement by 25%[63] compared to the 1995 Regulations. It was subsequently also claimed that they had achieved a 50% cut compared to the 1990 Regulations.[64]

While the u-value ceased being the sole consideration in 2006, u-value limits similar to those in the 2002 regulations still apply, but are no longer sufficient by themselves. The DER, and TER (Target Emission rate) calculated through either the UK Government's Standard Assessment Procedure for Energy Rating of Dwellings (SAP rating), 2005 edition, or the newer SBEM (*Simplified Building Energy Model) which is aimed at non-dwellings, became the only acceptable calculation methods. Several commercial energy modeling software packages have now also been verified as producing acceptable evidence by the BRE Global & UK Government. Calculations using previous versions of SAP had been an optional way of demonstrating compliance since 1991(?). They are now a statutory requirement (B. Reg.17C et al.) for all building regulations applications, involving new dwelling/buildings and large extensions to existing non-domestic buildings.

See also[edit]

- Energy in the United Kingdom

- Insulate Britain protests

- Climate Change and Sustainable Energy Act 2006

- Fuel poverty in the United Kingdom

- Housing in the United Kingdom

- Post War Building Studies

- Code for Sustainable Homes

- Energy Saving Trust

- Standby power

References[edit]

- ^ a b House of Commons – Environmental Audit – First Report

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 February 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Domestic Carbon Dioxide Emissions for Selected Cities Archived 26 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, British Gas, published 20 February 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ Pre-Budget Report 2006: Index Archived 1 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Budget 2007: Speech Archived 28 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Green Building Archived 7 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "New homes to be 'zero emission'". BBC News. 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2006. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ DTI Archived 9 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Jean Lambert Green MEP for London". Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2007.

- ^ DTI Archived 16 July 2006 at the UK Government Web Archive

- ^ DTI Archived 16 July 2006 at the UK Government Web Archive

- ^ DTI Archived 16 July 2006 at the UK Government Web Archive

- ^ "UK government's Green Deal to cut fuel bills". BBC.co.uk. 23 November 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1965/1373/pdfs/uksi_19651373_en.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1972/317/pdfs/uksi_19720317_en.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ BERR – Redirect Archived 25 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dwelling Carbon Dioxide Emission Rate[permanent dead link]

- ^ Standard Assessment Procedure for Energy Rating of Dwellings 2005, Building Research Establishment

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Pilkington Energy Efficiency Trust". Archived from the original on 2 May 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Microsoft Word - Report A.doc Archived 25 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Assessment of Energy Efficiency impact of Building Regulations Compliance Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, prepared by the Building Research Establishment for the Energy Saving Trust / Energy Efficiency Partnership for Homes, published 10 November 2004. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ Part L1 - an investigation into the reasons for poor compliance Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Energy Saving Trust, published 3 May 2006. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- ^ Time to put a stop to the disdain for regulations, Association for the Conservation of Energy, published March 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ Pre-Budget Report 2006 Archived 8 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, HM Treasury, published 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ UK to leap from 'laggard to leader' on carbon dioxide emissions, The Independent, published 24 February 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ HBF welcomes Government's environmental vision on housing Archived 20 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Home Builder's Federation, December 2006 press releases, published 15 December 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Government's 2016 zero-carbon homes target 'too unrealistic', Architects Journal, published 6 March 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Zero-carbon construction Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, M Briggs, RSPH, published January 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "Government brings sustainability closer to home with new mandatory Code". WWF. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Why we've resigned from the Zero Carbon Taskforce Archived 13 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine WWF UK, published 4 April 2011, accessed 4 April 2011

- ^ Government's U turn on Zero Carbon is anti-green and anti-growth Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine UK Green Building Council, published 23 March 2011, accessed 4 April 2011

- ^ Proposals for amending Part L of the Building Regulations and Implementing the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, Department for Communities and Local Government, published 23 July 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ a b Building a Greener Future: Towards Zero Carbon Development - Consultation Archived 16 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Department for Communities and Local Government, published 13 December 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ Building Regulations Energy efficiency requirements for new dwellings Archived 27 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, page 5, Department for Communities and Local Government, published July 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Communities and Local Government Archived 20 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ European Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (Directive 2002/91/EC) Official Journal of the European Communities, published 02-12-16. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Cooper calls for incentives to improve home energy ratings Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Government News Network, published 06-09-21. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ "Properties with higher EPC rating worth 7% more on average". Mortgage Introducer. 29 October 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Andrewguy (30 October 2020). "Homes with a higher energy rating worth 7% more". Book My EPC. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ New Scientist, November 2005

- ^ About Good and Advanced practice Archived 25 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Renewable Energy Association – News Article

- ^ "100: Monitoring the implementation of the Home Energy Conservation Act 1995 - Department for Communities and Local Government". Archived from the original on 20 September 2006. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- ^ Thirty year old Salford homes make case for passive design Building4Change, published 29 June 2011

- ^ Nicole Lazarus (October 2003). "Beddington Zero (Fossil) Energy Development: Toolkit for Carbon Neutral Developments - Part II". BioRegional. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Civic Trust Award Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ South Yorkshire Energy Centre

- ^ Leicester EcoHouse Archived 1 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Architects Brief Archived 12 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Leicester EcoHouse, published 2010

- ^ Sustainable Energy Academy

- ^ Arkitektur och byggd miljö: Institutionen för arkitektur och byggd miljö

- ^ R-2000 Energy Efficiency Home Program, Energy, Mines and Resources, Canada, published 1992. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Welcome to R-2000 Archived 26 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ www.passivhaustagung.de Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ House of Commons – Environmental Audit – First Report

- ^ [2] Archived 1 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "How much insulation do I need?". thinkinsulation. Knauf Insulation. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Solar Energy Applications in Houses, F Jäger, ISBN 0-08-027573-7, page 54

- ^ The Building Regulations 1976, ISBN 0-11-061676-6, page 96

- ^ DTI: Energy efficiency in the UK 1990-2000, pdf file Archived 17 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 2003 Energy White Paper Archived 25 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, page 34

External links[edit]

- BRE: Domestic Energy Fact File

- Energy Efficiency in Existing Buildings: The Role of Building Regulations Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- DEFRA - Domestic energy research

- University of Oxford - Oxford University 40% House initiative

- Leeds Metropolitan University: York Energy Demonstration Project (1998) Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Heriot-Watt University's Tarbase Project

- Resources

- In the media