Eric Liddell

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

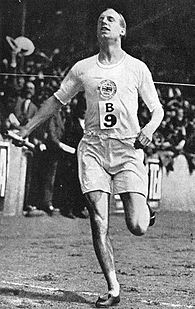

Liddell at the British Empire versus U.S.A. relays meet held at Stamford Bridge in July 1924[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Eric Henry Liddell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Scottish | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 16 January 1902 Tientsin, Qing China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 21 February 1945 (aged 43) Weihsien Internment Camp, Japanese China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Florence Mackenzie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3 daughters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Athletics, rugby union (7 tests) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Event(s) | 100m, 200m, 400m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Club | University of Edinburgh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Team | Great Britain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Achievements and titles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Olympic finals | 1924 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rugby union career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 埃里克·利德爾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 埃里克·利德尔 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Eric Henry Liddell (/ˈlɪdəl/; 16 January 1902 – 21 February 1945) was a Scottish sprinter, rugby player and Christian missionary. Born in Qing China to Scottish missionary parents, he attended boarding school near London, spending time when possible with his family in Edinburgh, and afterwards attended the University of Edinburgh.

At the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Liddell refused to run in the heats for his favoured 100 metres because they were held on a Sunday. Instead he competed in the 400 metres held on a weekday, a race that he won. He returned to China in 1925 and served as a missionary teacher. Aside from two furloughs in Scotland, he remained in China until his death in a Japanese civilian internment camp in 1945.

Liddell's Olympic training and racing, and the religious convictions that influenced him, are depicted in the Oscar-winning 1981 film Chariots of Fire, in which he is portrayed by fellow Scot and University of Edinburgh alumnus Ian Charleson.

Early life[edit]

Liddell was born 16 January 1902, in Tientsin, China, the second son of the Reverend and Mrs. James Dunlop Liddell, Scottish missionaries with the London Missionary Society. Liddell went to school in China until the age of five. At the age of six, he and his eight-year-old brother Robert were enrolled in Eltham College, a boarding school in south London for the sons of missionaries. Their parents and sister Jenny returned to China. During the boys' time at Eltham, their parents, sister, and new brother Ernest came home on furlough two or three times and were able to be together as a family, mainly living in Edinburgh.

At Eltham, Liddell was an outstanding athlete, earning the Blackheath Cup as the best athlete of his year, and playing for the First XI and the First XV by the age of 15, later becoming captain of both the cricket and rugby union teams. His headmaster, George Robertson, described him as being "entirely without vanity."[2]

While at the University of Edinburgh, Liddell became well known for being the fastest runner in Scotland. Newspapers carried stories of his feats at track events, and many articles stated that he was a potential Olympic winner.

Liddell was chosen to speak for Glasgow Students' Evangelistic Union by one of the GSEU's co-founders, D.P. Thomson, because he was a devout Christian. The GSEU hoped that he would draw large crowds to hear the Gospel. The GSEU would send out a group of eight to ten men to an area where they would stay with the local population. It was Liddell's job to be lead speaker and to evangelise the men of Scotland.

University of Edinburgh[edit]

In 1920 Liddell joined his brother Robert at the University of Edinburgh to study Pure Science. Athletics and rugby played a large part in his university life. He ran in the 100-yard and 220-yard races for the university, and played rugby for the University Club. He played for Edinburgh District in the inter-city matches against Glasgow District of 3 December 1921[3] and 2 December 1922,[4] from which he gained a place in the backline of a strong Scotland national rugby union team.

In 1922 and 1923, he played in seven out of eight Five Nations matches, and scored back-to-back tries in four appearances, which included wins over Ireland, France, and Wales.[5] While his main weapon was his speed, The Scotsman opined after Scotland's victory over Ireland in 1923 that "never again should it be held against him that he is 'only a runner'", and The Student wrote that Liddell had "that rare combination, pace and the gift of rugby brains and hands".[5] On the centenary of his first international cap against France in January 1922, Liddell was inducted into the Scottish Rugby Hall of Fame for his achievements.[5]

In 1923 he won the AAA Championships in athletics in the 100-yard race (setting a British record of 9.7 seconds that would not be equalled for 23 years)[6] and 220-yard race (21.6 seconds). He graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree after the Paris Olympiad in 1924.

Paris Olympics[edit]

The 1924 Summer Olympics were hosted by the city of Paris. A devout Christian, Liddell withdrew from the 100-metre race (his best event), because the heats were going to be held on a Sunday.[7] The schedule had been published several months earlier, and therefore his decision was made well before the Games.[citation needed] Liddell spent the intervening months training for the 400-metre race, though his best pre-Olympics time of 49.6 seconds, set in winning the 1924 AAA championship 440-yard race,[8] was modest by international standards. On the morning of the Olympic 400-metre final, 11 July 1924,[9] Liddell was handed a folded square of paper by one of the team masseurs. Reading it later he found the message: "In the old book it says: 'He that honours me I will honour.' Wishing you the best of success always." Recognising the reference to 1 Samuel 2:30, Liddell was profoundly moved that someone other than his coach believed in him and the stance he had taken.[10]

The pipe band of the 51st Highland Brigade played outside the stadium for the hour before he ran. The 400-metre had been considered a middle-distance event in which runners raced round the first bend before coasting down the back straight. Inspired by the Biblical message, and deprived of a view of the other runners because he drew the outside lane, Liddell raced the whole of the first 200 metres to be well clear of the favoured Americans.[11] With little option but to treat the race as a complete sprint, he continued to race around the final bend. He was challenged all the way down the home straight but held on to take the win. He broke the Olympic and world records with a time of 47.6 seconds.[12] It was controversially ratified as a world record, despite being 0.2 seconds slower than the record for the greater distance of 440 yards.[13]

A few days earlier Liddell had competed in the 200-metre finals, for which he received the bronze medal behind Americans Jackson Scholz and Charles Paddock, beating British rival and teammate Harold Abrahams, who finished in sixth place.[11] This was the second and last race in which these two runners met.[14]

His performance in the 400-metre race in Paris stood as a European record for 12 years, until beaten by another British athlete, Godfrey Brown, at the Berlin Olympics in 1936.[15][16]

After the Olympics and graduation from the University of Edinburgh, Liddell continued to compete. His refusal to compete on Sunday meant he had also missed the Olympic 4×400-metre relay, in which Britain finished third.[11] Shortly after the Games, his final leg in the 4×400-metre race in a British Empire vs. USA contest, helped secure the victory over the gold medal-winning Americans.[17] A year later, in 1925, at the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association (SAAA) meeting in Hampden Park in Glasgow, he equalled his Scottish championship record of 10.0 seconds in the 100-yard race, won the 220-yard contest in 22.2 seconds, won the 440-yard contest in 47.7, and participated in a winning relay team. He was only the fourth athlete to have won all three sprints at the SAAA, achieving this feat in 1924 and 1925. These were his final races on British soil.[11]

Because of his birth and death in China, some of that country's Olympic literature lists Liddell as China's first Olympic champion.[18]

Christian missionary work in China[edit]

Liddell returned to Northern China to serve as a missionary, like his parents, from 1925 to 1943 – first in Tianjin and later in the town of Xiaozhang,[19] Zaoqiang County, Hengshui, Hebei province, an extremely poor area that had suffered during the country's civil wars and had become a particularly treacherous battleground with the invading Japanese.[20]

During his time in China as a missionary, Liddell continued to compete sporadically, including wins over members of the 1928 French and Japanese Olympic teams in the 200- and 400-metre races at the South Manchurian Railway celebrations in China in 1928 and a victory at the 1930 North China championship. He returned to Scotland only twice, in 1932 and again in 1939. On one occasion he was asked if he ever regretted his decision to leave behind the fame and glory of athletics. Liddell responded, "It's natural for a chap to think over all that sometimes, but I'm glad I'm at the work I'm engaged in now. A fellow's life counts for far more at this than the other."[20]

Liddell's first job as a missionary was at the Anglo-Chinese College (grades 1–12) for wealthy Chinese students. The school's principal, Dr. Samuel Lavington Hart, who was educated at University of Cambridge, had been a prominent physicist before founding the school in 1902. Dr. Hart believed that by teaching the children of the wealthy, he would help them become influential figures in China and promote Christian values.[21] Liddell supported the school's mission and began teaching mathematics and science at the school in 1925.[22] Liddell also used his athletic experience to train boys in a number of different sports. According to one of Liddell's former students, Yu Wenji, Liddell "was very serious when protecting students' rights. He once quarreled with the headmaster to ask for more subsidies for students not from wealthy families."[23] One of Liddell's many responsibilities was that of superintendent of the Sunday school at Union Church, where his father was pastor. Liddell lived at 38 Chongqing Dao (formerly known as Cambridge Road) in Tianjin, where a plaque commemorates his residence. He also helped build the Minyuan Stadium in Tianjin.

During his first furlough from missionary work in 1932, he was ordained a minister of the Congregational Union of Scotland. On his return to China he married Florence Mackenzie, of Canadian missionary parentage, in Tianjin in 1934. Liddell courted his future wife by taking her for lunch to the Kiesling restaurant, which is still open in Tianjin.[citation needed] The couple had three daughters, Patricia, Heather, and Maureen, the last of whom he would not live to see. The school where Liddell taught is still in use today. One of his daughters visited Tianjin in 1991 and presented the headmaster of the school with one of the medals that Liddell had won for athletics.[citation needed]

In 1941 life in China had become so dangerous because of Japanese aggression that the British government advised British nationals to leave. Florence (who was pregnant with Maureen) and the children left for Canada to stay with her family when Liddell accepted a position at a rural mission station in Xiaozhang, which served the poor. He joined his brother, Rob, who was a doctor there. The station was severely short of help and the missionaries there were exhausted. A constant stream of locals came at all hours for medical treatment. Liddell arrived at the station in time to relieve his brother, who was ill and needing to go on furlough. Liddell suffered many hardships himself at the mission.

Internment[edit]

As fighting between the Chinese Army and invading Japanese troops[24] reached Xiaozhang, the Japanese took over the mission station and Liddell returned to Tianjin. In 1943, he was interned at the Weihsien Internment Camp (in the modern city of Weifang) with the members of the China Inland Mission, Chefoo School (in the city now known as Yantai), and many others. Liddell became a leader and organiser at the camp, but food, medicine, and other supplies were scarce. There were many cliques in the camp and when some rich businessmen managed to smuggle in some eggs, Liddell shamed them into sharing them. While fellow missionaries formed cliques, moralised, and acted selfishly, Liddell busied himself by helping the elderly, teaching Bible classes at the camp school, arranging games, and teaching science to the children, who referred to him as Uncle Eric.[25]

It was also claimed that one Sunday Liddell refereed a hockey match to stop fighting amongst the players, as he was trusted not to take sides. One of his fellow internees, Norman Cliff, later wrote a book about his experiences in the camp called "The Courtyard of the Happy Way" (Chinese 樂道院, also translated as "The Campus of Loving Truth"),[26] which detailed the remarkable characters in the camp. Cliff described Liddell as "the finest Christian gentleman it has been my pleasure to meet. In all the time in the camp, I never heard him say a bad word about anybody". Langdon Gilkey, who also survived the camp and became a prominent theologian in his native America, said of Liddell: "Often in an evening I would see him bent over a chessboard or a model boat, or directing some sort of square dance – absorbed, weary and interested, pouring all of himself into this effort to capture the imagination of these penned-up youths. He was overflowing with good humour and love for life, and with enthusiasm and charm. It is rare indeed that a person has the good fortune to meet a saint, but he came as close to it as anyone I have ever known."[20][27]

Death[edit]

In his last letter to his wife, written on the day he died, Liddell wrote of suffering a nervous breakdown due to overwork. He had an undiagnosed brain tumor; overwork and malnourishment may have hastened his death. Liddell died on 21 February 1945, five months before liberation. Langdon Gilkey later wrote, "The entire camp, especially its youth, was stunned for days, so great was the vacuum that Eric's death had left."[27] According to a fellow missionary, Liddell's last words were, "It's complete surrender", in reference to how he had given his life to God.[28] According to a different source, the 2007 documentary film Eric Liddell: Champion of Conviction, Liddell had been in and out of the camp hospital due to the brain tumor. One of his students, Joyce Stranks, came to visit him in the hospital to discuss a book he had written about surrender to God's will. While discussing the book, Liddell reached a point when he was unable to complete saying the word "surrender," and instead he said "surren-...surren-" and after this his head fell back to his pillow and he died.[29]

Legacy[edit]

On 5 June 1945 the Eric Liddell Memorial Committee was set up in Glasgow, to seek donations for a fund to provide for the education and maintenance of Eric Liddell's three daughters; to fund an Eric Liddell Missionary Scholarship at the University of Edinburgh and an Eric Liddell Challenge Trophy for Amateur Athletics; and to erect a memorial in North China to commemorate Eric Liddell's work there. Only the first and third objectives were achieved.[30] To raise funds and to widen its appeal, the committee published a pamphlet by D.P. Thomson: Eric Liddell, The Making of an Athlete and the Training of a Missionary. The Fund was eventually wound up in 1954, having raised £3,687 15s - over £88,000 in relative purchasing power.[31] D.P. Thomson also spoke at well-attended memorial services held in both Edinburgh and Glasgow in 1945.[32]

When Scotsman Allan Wells won the 100-metre sprint at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, 56 years after the 1924 Paris Olympics, he was asked if he had run the race for Harold Abrahams, the last 100-metre Olympic winner from Britain (who had died two years previously). "No", Wells replied. "I would prefer to dedicate this to Eric Liddell".[33]

In 2002, when the first inductees were inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, Eric Liddell topped the public vote for the most popular sporting hero Scotland had ever produced.[34][35] Liddell was inducted into the Scottish Rugby Hall of Fame in January 2022, on the centenary of his first international cap.[36][5]

In 2008, just before the Beijing Olympics, Chinese authorities claimed that Liddell had refused an opportunity to leave the camp, and instead gave his place to a pregnant woman. Apparently, the Japanese and British, with Churchill's approval, had agreed upon a prisoner exchange.[11] However, his friends and those who had lived with him in the camp disputed the claim.[37]

Memorial[edit]

Liddell was buried in the garden behind the Japanese officers' quarters, his grave marked by a small wooden cross. The site was forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1989, in the grounds of what is now Weifang Middle School[11] in Shandong Province, north-east China, 480 km (298 mi) south of Beijing. Its rediscovery was largely the result of the determination of Charles Walker, a civil engineer working in Hong Kong, who felt that one of Scotland's great heroes was in danger of being forgotten.[38] Walker began looking for the unmarked grave in 1987, and eventually located it from a map drawn by another inmate in 1945, and the accounts of other witnesses who confirmed the location.[39]

In 1991 the University of Edinburgh erected a memorial headstone, made from Isle of Mull granite and carved by a mason in Tobermory, at the former camp site in Weifang. The simple inscription came from the Book of Isaiah 40:31: "They shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run and not be weary." The city of Weifang commemorated Liddell during the 60th anniversary of the internment camp's liberation by laying a wreath on his grave.

The Eric Liddell Centre was set up in Edinburgh in 1980 to honour Liddell's beliefs in community service whilst he lived and studied in Edinburgh. Local residents dedicated it to inspiring, empowering, and supporting people of all ages, cultures, and abilities, as an expression of compassionate Christian values.[40]

Eltham College's sports centre was named "Eric Liddell Sports Centre" in his memory.

In 2012 the University of Edinburgh launched a high-performance sports scholarship named after Liddell.[41] It was announced during a visit by Patricia Russell, Liddell's oldest daughter.[42]

In 2023, the Eric Liddell Gym, a fitness centre at the University of Edinburgh, was opened.[43]

Portrayals on film, TV and stage[edit]

- The Oscar-winning 1981 film Chariots of Fire revolves around Liddell and fellow sprinter Harold Abrahams. In it, Liddell is portrayed by Ian Charleson.

- In the 2007 film series The Torchlighters: Heroes of the Faith, Eric Liddell is portrayed in the film "The Eric Liddell story", depicting his life and work as a Christian missionary.

- In 2012, the play Chariots of Fire, based on the 1981 film, starred Jack Lowden as Liddell.

- A 2016 film, On Wings of Eagles (Chinese name 终极胜利, and original English name The Last Race), produced by Beijing Forbidden City Studio, directed by Hong Kong director Stephen Shin, stars Joseph Fiennes as Liddell, and portrays his return to China and the rest of his life after the 1924 Olympics.[44]

Chariots of Fire[edit]

The 1981 film Chariots of Fire chronicles and contrasts the lives and viewpoints of Liddell and Harold Abrahams. One inaccuracy surrounds Liddell's refusal to race in the 100-metre event at the 1924 Paris Summer Olympics. The film portrays Liddell as finding out that one of the heats was to be held on a Sunday as he boards the boat that will take the British Olympic team across the English Channel to Paris. In reality, the schedule and Liddell's decision were both known several months in advance, though his refusal to participate remains significant. Liddell had also been selected to run as a member of the 4×100-metre and 4×400-metre relay teams at the Olympics, but he also declined these spots as the finals were to be run on a Sunday.[45][46]

One scene in the film depicts Liddell falling early in a 440-yard race in a Scotland–France dual meet and making up a 20-yard deficit to win; the actual race was during a Triangular Contest meet between Scotland, England and Ireland at Stoke-on-Trent in England in July 1923. Liddell was knocked to the ground several strides into the race. He hesitated, got up and pursued his opponents, 20 yards ahead. He caught the leaders shortly before the finish line and collapsed after crossing the tape.[citation needed] This scene was filmed at Goldenacre stadium in Edinburgh, the playing fields of George Heriot's School in Edinburgh.

Producer David Puttnam viewed footage from a 1924 film of Liddell and Abrahams while researching the film with scriptwriter Colin Welland,[47][48] and Liddell's unorthodox running style as portrayed in the film, with his head back and his mouth wide open, is also said to be accurate. At an athletics championship in Glasgow, a visitor watching the 440-yard final, in which Liddell was a long way behind the leaders at the start of the last lap (of a 220-yard track), remarked to a Glasgow native that Liddell would be hard put to win the race. The Glaswegian merely replied, "His head's no' back yet." Liddell then threw his head back and, with mouth wide open, caught and passed his opponents to win the race.[citation needed] In the 1945 report of his death The Guardian wrote, "He is remembered among lovers of athletics as probably the ugliest runner who ever won an Olympic championship. When he appeared in the heats of the 400m at Paris in 1924, his huge sprawling stride, his head thrown back and his arms clawing the air, moved the Americans and other sophisticated experts to ribald laughter." Rival Harold Abrahams said in response to criticism of Liddell's style: "People may shout their heads off about his appalling style. Well, let them. He gets there."[11]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ John W Keddie, "Running the Race - Eric Liddell, Olympic Champion and Missionary" book.

- ^ Caughey, Ellen (2000). Eric Liddell: Olympian and Missionary. Ulrichsville, OH: Barbour Pub. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-57748-667-1.

- ^ "The Glasgow Herald - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "The Glasgow Herald - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ a b c d Oliver, David (2 January 2022). "Eric Liddell enters Scottish Rugby Hall of Fame after 'other' sporting career before Chariots of Fire recognised". The Scotsman.

- ^ British 100 yards record equalled The Advocate 6 August 1946

- ^ "Eric Liddell". Olympedia. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Lovesey, Peter (1979). The Official Centenary History of the Amateur Athletic Association. Enfield, Great Britain: Guinness Superlatives Ltd. p. 77. ISBN 0-900424-95-8.

- ^ "Golden Scots: Eric Liddell, running to immortality". BBC web-site. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ Hamilton, Duncan (2016). For the glory. Doubleday. pp. 91, 339.

- ^ a b c d e f g Simon Burnton (4 January 2012). "50 stunning Olympic moments No8: Eric Liddell's 400 metres win, 1924". The Guardian.

- ^ "The Official Report of the Games of the 8th Olympiade" (PDF). Paris, FR. 1924. p. 107. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Watman, Mel (2006). All-Time Greats of British Athletics. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: SportsBooks Ltd. p. 17.

- ^ Liddell had finished some five yards ahead of Abrahams in a 220-yard semi-final at the 1923 AAA Championships. Watman, Mel (2006). All-Time Greats of British Athletics. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: SportsBooks Ltd. p. 16.

- ^ García, José María. "Progresión de los Récords de Europa al Aire Libre" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Sparks, Bob (31 December 2002). "European Records Progression (Men)". Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Eric Liddell". sports-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Chariots of Fire's Liddell, a Chinese hero? – By Nick Mulvenney (6 August 2008) Reuters

- ^ Xiaozhang was spelled as Siaochang in most Western documents according to Wade-Giles system.

- ^ a b c Burnton, Simon (4 January 2012). "50 stunning Olympic moments: No8 Eric Liddell's 400 metres win, 1924". The Guardian.

- ^ Hamilton, Duncan (2016). For the Glory: The Untold and Inspiring Story of Eric Liddell, Hero of Chariots of Fire. Penguin Press.

- ^ McCasland, David. Pure Gold. Discover House. p. 126.

- ^ Kaihao, Wang. "Olympians are Forever".

- ^ Magnusson, Sally (1981). The Flying Scotsman, A Biography. New York, NY, USA: Quartet Books. pp. 123–32..

- ^ Jackson(?), p. 21

- ^ Magnusson, Sally (1981). The Flying Scotsman, A Biography. New York, NY, USA: Quartet Books. p. 150..

- ^ a b Gilkey, Langdon (1966). Shantung Compound (14th ed.). San Francisco: Harper & Row. p. 192. ISBN 0-06-063112-0.

- ^ Magnusson, Sally (1981). The Flying Scotsman, A Biography. New York, NY: Quartet Books Inc. p. 160-170

- ^ Eric Liddell: Champion of Conviction (Motion Picture). 2007.

- ^ "Eric Liddell Memorial Fund". Archives Hub. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Relative Values". Measuring Worth. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ Magnusson, Sally (1981). The Flying Scotsman: The Eric Liddell Story (2009 ed.). Stroud: Tempus Publishing / The History Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-7524-4352-2.

- ^ "Thrilled to follow in Liddell's footsteps". The Scotsman. 3 September 2000.

- ^ "Eric Liddell – Scotland's most popular sporting hero". The Scotsman. 1 December 2002. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Scottish Athletes Prominent in Hall of Fame". Scottish Athletics. 2 December 2002. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Eric Liddell: Olympic champion inducted into Scottish Rugby Hall of Fame". BBC. 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Hamilton 2016 p.321.

- ^ "Charles Walker: Civil engineer and Eric Liddell devotee (obituary)". heraldscotland.com. 23 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Wong Sau-Ying (15 December 1990). "From Olympic Track To China, Eric Liddell's Spirit Lives On". apnews.com. The Associated Press. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "The Eric Liddell Centre". The Eric Liddell Centre. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Eric Liddell Sports Scholarships launched". Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Davidson, Gina (19 June 2012). "My daddy, the Flying Scotsman". The Scotsman. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ "Eric Liddell commemorated as university gym is named after Scots Olympic legend". The Herald. Glasgow. 17 October 2023. p. 3.

- ^ "On Wings of Eagles (2017)". IMDb.

- ^ The Flying Scotsman: The Eric Liddell Story (1981) p. 42, Sally Magnusson

- ^ Olympedia - Athletics Timetable 1924

- ^ "CHARIOTS OF FIRE 1924 Film Footage Discovered At BFI". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Running with Harold Abrahams (1924)". British Film Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

Further sources[edit]

Archives[edit]

- The Eric Liddell Centre's website has a comprehensive range of information, photographs, videos and stories on Eric Liddell donated and written by his family. Eric Liddell Centre

- Papers relating to Liddell's life as a missionary are held at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. Special Collections | SOAS Library | SOAS University of London

- Papers relating to The Eric Liddell Memorial Committee and Fund are held at Lloyds Banking Group Archives (Edinburgh),[1] reference Number GB 1830 LID.Eric Liddell Memorial Fund - Archives Hub

- D.P. Thomson's papers relating to Eric Liddell are held in the D.P. Thomson Archive by the Church of Scotland's Council on Mission and Discipleship: Mission and Discipleship Council

Bibliography[edit]

- Janet & Geoff Benge. Eric Liddell: Something Greater Than Gold. Youth with a Mission Publishing, 1999. ISBN 1-57658-137-3

- Eric Liddell pages on the Eric Liddell Centre website. Text approved by Eric Liddell's daughters.

- Ellen Caughey, Eric Liddell: Olympian and Missionary Barbour Books, 2000. ISBN 1-57748-667-6

- Langdon Gilkey. Shantung Compound Harper & Row, 1966, pp. 192–193. ISBN 0-06-063113-9

- Marjorie I.H. Jackson, God's Prisoner of War Calvary Church, Lancaster, PA, 2006. (eyewitness account of a Weihsien Camp survivor)

- John Keddie (& Sebastian Coe), Running the Race Evangelical Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-85234-665-5

- Eric Liddell, The disciplines of the Christian life, Abingdon Press, 1985.

- Eric Liddell, The Sermon on the Mount: notes for Sunday School teachers.

- David McCasland, Eric Liddell: Pure Gold: A New Biography of the Olympic Champion Who Inspired Chariots of Fire. Discovery House Publishers, 2003. ISBN 1-57293-130-2

- Sally Magnusson. The Flying Scotsman Quartet Books, 1981. ISBN 0-7043-3379-1

- Russell Ramsey, God's Joyful Runner Bridge-Logos Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0-88270-624-1

- Catherine Swift, Eric Liddell Bethany House Publishers, 1990. ISBN 1-55661-150-1

- D.P. Thomson, Eric Liddell: The Making of an Athlete and the Training of a Missionary Glasgow: The Eric Liddell Memorial Committee 1946

- D.P. Thomson, Scotland's Greatest Athlete: The Eric Liddell Story Crieff: The Research Unit 1970. ISBN 0900867043.

- D.P. Thomson, Eric H. Liddell: Athlete and Missionary Crieff: The Research Unit 1971. ISBN 0900867078.

- Williams, David A. "Eric Liddell and his father, James Liddell: Hollywood Hid a Congregationalist" (PDF). World Evangelical Congregational Fellowship. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- Julian Wilson, Complete Surrender Monarch Publications, 1996. ISBN 1-85424-348-9

- Ronald Clements, In Japan the Crickets Cry Monarch Publications, 2010. ISBN 978-1-85424-970-8 (eyewitness account of Weihsien Camp survivor, Stephen A. Metcalf)

- Duncan Hamilton, For the Glory Doubleday, 2016. ISBN 978-0-85752-259-7

- Eric Eichinger, "The Final Race" Tyndale House, 2018. ISBN 978-1-49641-994-1

Film[edit]

- Chariots of Fire (1981 feature film)

- The Story of Eric Liddell (2004 documentary)

- Eric Liddell: Champion of Conviction (2007 documentary)

- Torchlighters: The Eric Liddell Story (2007 animation)

- On Wings of Eagles (2016 feature film)

External links[edit]

- Eric Liddell The Eric Liddell Centre, Edinburgh

- Biography The Eric Liddell Sports Centre, Eltham College

- Beyond the Chariots, Rich Swingle's one-man play about Eric Liddell's life in China

- Eric Liddell at the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame

- Eric Liddell at ESPNscrum

- Commonwealth War Graves database entry

- Eric Liddell at Find a Grave

- Eric Liddell at Olympics.com

- Eric Liddell at Olympedia