Ewing Young

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Ewing Young | |

|---|---|

| Born | Before 1794 |

| Died | Feb. 9, 1841 |

| Occupation(s) | Trapper, businessman |

| Spouse | María Josefa Tafoya |

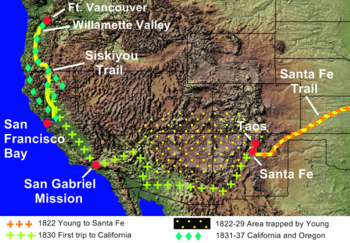

Ewing Young (1799-February 9, 1841) was an American fur trapper and trader from Tennessee who traveled in what was then the northern Mexico frontier territories of Santa Fe de Nuevo México and Alta California before settling in the Oregon Country. Young traded along the Santa Fe Trail, followed parts of the Old Spanish Trail west, and established new trails. He later moved north to the Willamette Valley. As a prominent and wealthy citizen in Oregon, his death was the impetus for the assemblies that several years later established the Provisional Government of Oregon.[1]

Early life[edit]

Ewing Young was born in Tennessee to a farming family in 1799.[1] In the early 1820s he had moved to Missouri, then the far western edge of the American frontier, not far from the border of the Spanish-controlled territories of present-day Texas, New Mexico and the Southwestern United States. While residing in Missouri he farmed briefly on the Missouri River at Charitan.[1]

New Mexico[edit]

Under the Spanish colonial system, trade between Americans and the Spanish outpost at Santa Fe was prohibited, but with the end of the Mexican War of Independence Spanish authorities were removed from the area in 1821. American traders, mainly operating out of St. Louis, Missouri, were eager to test whether commercial activities in Santa Fe would now be allowed, and a small group of Americans returned successfully in December 1821 from a small trading foray. At age 18, Young sold the farm he had recently purchased and eagerly signed up to join a somewhat larger group bound for Santa Fe.[2] In May 1822 this party departed, becoming the first overland wagon train to traverse the Santa Fe Trail.[2] Young and the others found that they were welcomed by the new Mexican authorities in Santa Fe.[2]

The Spanish and later Mexicans had not focused on trapping fur-bearing animals of the Southwest as demand was small within the Spanish trading system.[citation needed] Expeditions of the Hudson's Bay Company, the American Fur Company and others established the North American fur trade (mainly beaver) in response to demand for furs in American and European markets, and the new trail opened up fresh hunting grounds. For the next nine years Young pioneered trapping in the region, dividing his time between Santa Fe and Missouri.[2] He led many of the first American expeditions into the mountains and watercourses of the present-day states of New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and Arizona.

Young and his associates established a commercial route between Nuevo México and Missouri that exchanged Mexican furs, horses and mules for American-produced trade goods.[3] When they returned to Nuevo Mexico, they sold the American goods for gold and silver coin.[2] During the trapping expedition of 1827–1828, Young employed a teenaged Kit Carson.[4] Despite tension that developed with Mexican authorities trying to restrict American activities, Young became a successful trapper and businessman. He eventually set up a trading post in Pueblo de Taos in northern Nuevo Mexico, in the late 1820s.[4] During his time in Mexico he was generally called Joachin John[3] or Joaquin Jóven by fellow inhabitants.[5]

California[edit]

In the spring of 1830, Young led the first American trapping expedition to reach the Pacific Coast from Santa Fe, traveling via the Salt River, Gila and Verde rivers, then cross-country to the Colorado River[6] and on across the Mojave Desert following the trail marked three years before by Jedediah Smith, eventually arriving at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, where they recuperated. The group then visited Mission San Fernando Rey de España on their way north into California's great Central Valley via its southern San Joaquin Valley section.[7]

Once there, the group moved north to the Sacramento Valley, where they encountered Peter Skene Ogden of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). The two groups jointly trapped the valley before the Americans set off for the Tule River.[5] After a short trapping excursion there, the party encountered an official from the Mission San José, who was trying capture members of the mission, possibly Ohlone people.[5] With the aid of eleven of Young's trappers the "fugitives" were taken back to the mission, where Young visited on 11 July.[5] From here the Americans moved on to San Francisco Bay to trade their pelts. After this they went south to Pueblo de Los Angeles and then back to Taos before the end of 1830. At the time of his return to Taos with the proceeds of this expedition, Young was established as one of the wealthiest Americans in Mexican territory.[7]

Over the next few years, Young and his group continued traveling to Alta California to trap and trade. In 1834 in San Diego, Young encountered Hall J. Kelley, the great promoter of the Oregon Country from Boston. Kelley invited Ewing Young to accompany him north to Oregon, but Young at first declined. After re-thinking, Young agreed to travel with Kelley and they set out in July 1834, with a group including Webley John Hauxhurst and Joseph Gale, both prominent figures in the Willamette Valley, accompanying them.[8]

Oregon Country[edit]

Young and Kelley arrived at the Hudson's Bay Company post Fort Vancouver on October 17, 1834, center of the Columbia District.[9] The HBC was the preeminent economic force in the region's fur trade.[9] At the time the Oregon Country was jointly occupied by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United States of America. Young decided to settle permanently on the west bank of the Willamette River, near the mouth of Chehalem Creek, opposite Champoeg.[10] His home is believed to be the first house built by European Americans on that side of the river.[10] Dr. John McLoughlin of the HBC tried to discourage American settlers in the region.[citation needed] The Mexican government of Alta California accused Young and his group of having stolen 200 horses when they left.[10] The group denied this, saying some uninvited traveling companions had stolen the horses.[10] McLoughlin blacklisted Young from doing business with the HBC.[11]

In 1836, Young secured a vat from Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth's failed post on Wapato Island and began a distillery to produce alcohol.[12] The Methodist Mission superintendent Jason Lee organized the Oregon Temperance Society and, along with McLoughlin, tried to get Young to stop his efforts.[11] McLoughlin and the HBC prohibited alcohol sales to the Indigenous peoples, as they had seen that it caused problems.[11] Late in the year, U.S. Navy Lieutenant William A. Slacum arrived on the ship Loriot and helped to dissuade Young from following through on the venture.[11]

Willamette Cattle Company[edit]

Slacum was an agent of the U.S. President; he helped put together a joint venture among the men to purchase cattle.[11] In January 1837, Young was selected as the leader of the Willamette Cattle Company. He traveled to California on the Loriot (assisted by Slacum). After purchasing 630 head of cattle, he brought them back along the Siskiyou Trail. Previously, the HBC had owned all the cattle in the Willamette Valley and rented animals to settlers.[9][13] Accompanying Young on the cattle drive were Philip Leget Edwards, Calvin Tibbets, John Turner, William J. Bailey, George Gay, Lawrence Carmichael, Pierre De Puis, Benjamin Williams, and Emert Ergnette.[14] During the drive Gay and Bailey murdered a native boy, rationalizing it as justice for the attack two years earlier by the Rogue River Indians on Young’s group.[1]

Marriage and family[edit]

He took María Josefa Tafoya, the daughter of a prominent Taos family who were Mexican citizens, as his wife in a common-law marriage.[4] By the late 1820s and early 1830s, the Mexican authorities were growing concerned about American settlers and their influences in Nuevo México. They began to impose increasingly severe restrictions on trade and trapping. Perhaps in part to avoid these restrictions, Young was baptized a Catholic in 1830 (perhaps he also became a Mexican citizen and formalized his marriage to Maria Tafoya; however, if he did so, no record of these two events survives).[15]

Legacy[edit]

In February 1841, Young died without any known heir and without a will.[9] This created a need for some form of probate court to deal with his estate, which had many debtors and creditors among the settlers.[9] Doctor Ira L. Babcock was selected as supreme judge with probate powers to deal with Young's estate.[16] The activities that followed his death eventually led to the creation of a provisional government in the Oregon Country.[9]

The Ewing Young Historical Marker located along Oregon Route 240 notes the location of Young's farm and grave.[17][18]

Ewing Young Elementary School in Newberg, Oregon, is named in his honor.[19] In 1942 the Liberty ship Ewing Young (hull #631 from Calships in Terminal Island, California) was named in his honor. The Ewing Young served in the Pacific theater during World War II and was scrapped in 1959.[citation needed]

Ewing Young Heritage Oak Tree[edit]

On May 6, 1846, an acorn was planted on Young’s grave near his cabin site by Miranda Bayley and Sidney Smith. The oak still survives as of 2018 and was listed among Oregon's Heritage Trees on April 7, 1999. It is located 4 miles (6.4 km) west of Newberg, Oregon on private property but can be seen from Highway 240. In 2011 the tree had a 14 feet 8 inches (4.47 m) trunk circumference and a crown measuring 88 feet (27 m).[20]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d "Ewing Young Route". Oregon's Historic Trails. End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center. Archived from the original on 2006-12-10. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- ^ a b c d e Holmes, Kenneth (1967). Ewing Young:master trapper. Portland, Oregon: Binsford & Mort. pp. 9–20.

- ^ a b Young, F. G. and Joaquin Young "Ewing Young and His Estate: A Chapter in the Economic and Community Development of Oregon." The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 21, No. 3 (1920), pp. 171-315.

- ^ a b c Holmes, Kenneth (1967) p. 40-43.

- ^ a b c d Bancroft, Hubert History of California, Volume III San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft & Co. 1885, pp. 174-175

- ^ Utley, R. M. (1997). A life wild and perilous: Mountain men and the paths to the Pacific. New York: Henry Holt and Co. (chapter 8)

- ^ a b Holmes, Kenneth (1967) pp. 46-60

- ^ The American Rocky Mountain Fur Trade

- ^ a b c d e f Bancroft, Hubert and Frances Fuller Victor. History of Oregon, San Francisco: History Co., 1890

- ^ a b c d Hussey, John A. Champoeg: Place of Transition, A Disputed History. Portland: Oregon Historical Society. 1967, pp. 73-74

- ^ a b c d e Terry, John (October 15, 2006). "Oregon's Trails - Pariah eases into spirited endeavor". The Oregonian. pp. Regional News, Pg. B11.

- ^ Allen, A. J. years in Oregon. Ithaca, NY: Mack, Andrus, & Co. 1848. p. 78

- ^ Slacum, William A. "Memorial of William A. Slacum." The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society p. 196

- ^ "Wallamette Settlement Articles of Agreement". Provisional and Territorial Records. Oregon Provisional Government: 406. 1837-01-13.

- ^ Holmes, Kenneth (1967) pp. 64-65

- ^ Horner, John B. (1921). Oregon: Her History, Her Great Men, Her Literature. The J.K. Gill Company:Portland, Oregon.

- ^ "Ewing Young Historical Marker". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1980-11-28. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Munford, Kenneth; Charlotte L. Wirfs (1981). "The Ewing Young Trail". Benton County Historical Society & Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Ewing Young History. Archived 2008-02-29 at archive.today Newberg School District. Retrieved on March 24, 2008.

- ^ Madeline MacGregor (September 24, 2011). "Ewing Young Oak". Salem, Oregon: Oregon Travel Experience. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

References[edit]

- Carter, Harvey L. "Ewing Young", featured in "Trappers of the Far West", Leroy R. Hafen, editor. 1972, Arthur H. Clark Company, reprint University of Nebraska Press, October 1983. ISBN 0-8032-7218-9

- Holmes, Kenneth (1967). Ewing Young:master trapper. Portland, Oregon: Binsford & Mort. ISBN 978-0-8323-0061-5.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis "Dear Old Kit": The Historical Christopher Carson, University of Oklahoma Press, hardcover (1968), 250 pages; trade paperback reprint, University of Oklahoma Press (August 1990), 250 pages, ISBN 0806122536 ISBN 978-0806122533 Pages 38 to 150 of "Dear Old Kit" consist of an annotated edition of "The Kit Carson Memoirs, 1809–1856", an original manuscript dictated by Kit Carson with 322 annotations by Carter.