Gargoyle Club

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

The Gargoyle Club was a private club on the upper floors of 69 Dean Street, Soho, London, at the corner with Meard Street. It was founded on 16 January 1925[1] by the aristocratic socialite David Tennant, son of the First Baron Glenconner. David was the brother of Stephen Tennant who was a prominent member of the social set called "Bright Young People" and of Edward Tennant, the poet who was killed in action in World War I.

Before Tennant[edit]

This elegant house, 69 and 70 Dean Street,[2] a pair of Georgian residences, was built on the Pitt estate[3] in 1732–1735[4] by John Meard, the carpenter who helped standardise the Georgian town house.

- Later occupants of No. 70[3] included :

- Sir William Wolseley, 5th Baronet, 1734–5

- Robert Marsham, second Baron Romney, 1736–40

- Sir Thomas Wilson, knight and 'agent', 1761–74).

- Later occupants of No. 69[3] included :

- George Wandesford, 4th Viscount Castlecomer (1687–1751), in 1750;

- Sir John Wynn, 2nd Baronet, 1755–73

- Baron Grant in 1775;

- Sir Lionel Darell, 1st Baronet, 1775–95

- (Sir) Thomas Bell, 1796–1824

"In 1834 No. 69 was taken by Vincent Novello, the composer and musical editor, and his son, Joseph Alfred, music seller and publisher, who were perhaps responsible for the erection of the back premises, with the wall still fronting Meard Street. Vincent's daughter, Clara, the singer, was also living here in 1840 and the painter, J. P. Davis, in 1842. In 1847 the firm of Novello became music printers also. It was probably in 1864–5 that the upper storeys were added to No. 69 to accommodate the printing works. In 1867 the firm removed to Berners Street but in 1871 the printing works returned to No. 69, and No. 70 was bought in 1875 for the storage of plates. Thenceforward the firm occupied both houses until 1898, when it moved to new printing works in Hollen Street."

Survey of London[3][5]

David Tennant[edit]

David Tennant took a 50-year lease on the upper three floors, while an existing printing works[6][7][8] established by the Novello music publishing family remained housed beneath.[9] Here he created a private apartment, a very large ballroom, a Tudor Room, coffee room, drawing room and a 350-sq yds flat roof with a garden for dining and dancing, around which neighbouring chimneys were painted brilliant red. All who visited the club shared its intimately democratic and rickety external lift, four-person maximum, enclosed in shining metal like an art-nouveau cabin trunk,[10] located round the corner in Meard Street.

The charismatic Tennant was the self-appointed ringmaster to an arena where Bohemians could mingle comfortably with the upper crust, according to writer and film producer Michael Luke.[11][12]

Of the club's opening night The Daily Telegraph observed that its 300-strong list of members "probably contains more famous names in society and the arts than any other purely social club". Names on this list included Somerset Maugham, Noël Coward, Gladys Cooper, Leon Goossens, Gordon Craig, George Grossmith, Virginia Woolf, Duncan Grant, Nancy Cunard, Adèle Astaire, Edwina Mountbatten; an obligatory Guinness, Rothschild and Sitwell; MPs, and peers of the realm.[13]

Decor[edit]

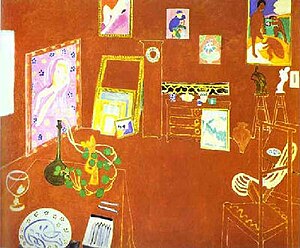

Designed by Henri Matisse, Edwin Lutyens, and Augustus John,[17] the interior decor was theatrical – a fountain on the dance floor,[18][19] log fires in the dining room, wooden gargoyles suspended as lanterns – with a strong Moorish flavour. Henri Matisse was made an honorary member after advising on decor.[20] To complement the main club-room's elaborate coffered ceiling painted with gold leaf, like the Alhambra, he suggested covering the walls entirely with a mosaic of imperfectly cut glass tiles from an 18th-century chateau.[21] Matisse himself designed a stunning entrance staircase to this room in glittering steel and brass, which remained in use until the club's conversion into a studio complex in the mid-1980s.

The young Tennant bought two of Matisse's paintings in Paris for £600 and in the opinion of Anthony Powell they "lent an air of go-ahead culture to the club". These were the painter's daring and inventive The Red Studio from 1911 which was displayed in the bar[22] at the Gargoyle until 1941, offered to the Tate Gallery for £400 and declined, then in 1949 joined the MoMA permanent collection in New York where it still hangs.[23] The other Matisse, The Studio, Quai St Michel (1916), features his favourite model the voluptuous Lorette, naked on a couch, on the club's stairs.[22] Today she resides in Washington DC in The Phillips Collection,[24] after Tennant, feeling himself to be on the verge of ruin, sold it for "a derisory sum" to Douglas Cooper, who in turn sold it on.[25]

"The decor is bright but tasteful and Matisse gave his expert advice. Several of his drawings of ballet girls grace the upstairs bar which is a cheerful spot always crowded with people discussing art, politics or women in the liveliest way. ‘My unpaid cabaret,’ David Tennant calls them… The restaurant downstairs seats 140 and its ceiling and general design have been modelled on the Alhambra at Granada. The mirrors are particularly attractive, unless you have drunk too much gin!... The four-piece band led by Alec Alexander, suits the style of the club. It delivers lively, cheerful music that you can dance to without having your nerves torn to shreds. Alec knows all the members and seems to enjoy playing requests." – Stanley Jackson, 1946[26]

After Tennant[edit]

In 1952 David Tennant sold the Gargoyle as a declining[27] concern[28][29] for £5,000 to caterer John Negus[30] and it remained popular among the generation of Francis Bacon, Antonia Fraser and Daniel Farson who would often go on from the Colony Room which was founded in 1948 by Muriel Belcher across at 41 Dean Street. For years the Gargoyle was one of the few places in London serving drinks at affordable prices after midnight. In 1955 the club was sold on to Michael Klinger[31] and Jimmy Jacobs[32] who relaunched it as a strip club[33][34] called the Nell Gwynne (variously advertised as a Theatre, Club, or Revue).[35][36][37][38][39][40][41] A 1960s ad shows the club as the Nell Gwynne by day and the Gargoyle Club at night.[42][43]

On 19 May 1979 in the Gargoyle's rooftop club space Hammersmith-born insurance salesman Peter Rosengard[44] started a weekly club night on Saturdays called the Comedy Store, in partnership with comedian Don Ward. It was modelled on the original in Los Angeles, and invited audiences to show approval or disapproval of the unknown acts performing by "gonging" them off.[45] The London Comedy Store made the reputations of many of the UK's upcoming "alternative comedians". Among the original line-up here were Alexei Sayle, Rik Mayall, Adrian Edmondson, French & Saunders, Nigel Planer and Peter Richardson who in 1980 led these pioneers to establish the breakaway Comic Strip team elsewhere in Soho.[46] All were to prove influential in reshaping British television comedy throughout the 1980s as stars of The Comic Strip Presents.[47]

In July 1982, among many themed weekly club-nights, came the first incarnation upstairs in the Gargoyle Club of the Batcave,[48] a Wednesday night fronted by Olli Wisdom,[49] lead singer in the house band, Specimen, and guitarist Jon Klein as art director. Visitors included Robert Smith, Siouxsie Sioux, Steve Severin, Foetus, Marc Almond and Nick Cave. The Nell Gwynne strip-teasers were still performing from 2.30 pm until late evening, when they could be seen exiting via the rickety lift, even as Batcavers queued to come up.

By the year's end, when the upper floors were sold off, the one-nighters such as Batcave moved on. The Comedy Store moved to a series of other venues, taking over 28a Leicester Square (previously the Subway club) in 1985. It had become a template for the new style of stand-up comedy clubs that opened around the land. Don Ward dissolved his business relationship with Rosengard in late 1981[50] while remaining CEO of Comedy Store interests. In 1984 Rosengard went on to manage the band Curiosity Killed the Cat.

The Mandrake[edit]

A second private club became part of the story of 69 Dean Street during the postwar 1940s when an eccentric crowd started gathering in the Mandrake at No 4 Meard Street, a house only a few yards west of the Gargoyle's entrance with its tiny lift. An underground room was rented for a chess club by streetwise Teddy Turner and Bulgarian émigré Boris Watson (after a name change), though by 1953 one basement room beneath Meard Street had become six after knocking through walls underneath No 69, to include a reading room for the intellectuals. An advert claimed the Mandrake to be "London's only Bohemian rendezvous".[51] A year's membership cost half a guinea “in advance” and the bait was illustrated with a photograph of an artist sketching beside an image of a voluptuous nude. Pretty soon the offbeat broadcaster Daniel Farson was calling its barmaid Ruth Soho's equivalent of Manet's famous Suzon painted serving at A Bar at the Folies Bergère.

Regulars included Nina Hamnett, Brian Howard and Julian Maclaren-Ross for whom Watson would cash cheques in the form of credit behind the bar. Private membership clubs were allowed to stay open during the strict afternoon closing hours imposed on pubs by the licensing laws, as well as late into the early hours after the 10.30 pm closing time for pubs. One condition was that clubs were required to serve food with alcohol. Result: the Mandrake became notorious for its stale sandwiches piled behind the bar, in Watson's view available “for drinking with, not for eating”! Inevitably the drinkers grew to outnumber the thinkers. Soon a jukebox made its appearance along with live guitar and lute recitals, and impromptu jam sessions for jazz musicians such as pianist Joe Burns, bassists Wally Wrightman and Percy Borthwick, drummers Laurie Morgan and Robin Jones, trombonist Norman Cave, singer Cab Kaye and Ronnie Scott (later founder of Soho's pre-eminent jazz club), plus visitors such as the touring Duke Ellington band.[52] And the 1960s brought in the legendary painters and poets who were reinforcing Soho's reputation for general non-conformity. The kitchen was forced to upgrade and, according to Michael Luke, the Mandrake became "a launching pad for the Gargoyle – a place where loins could be girded and spirits stiffened for that challenging arena up above".[53]

By the 1970s the Mandrake had acquired a new pedimented entrance door on Meard Street, curiously now east of the Gargoyle's, just a couple of yards nearer to Dean Street. Its lease was then acquired by Soho's only Jamaican club owner, Vince Howard, who changed its name to Billy's. Vince Howard in the cover story of The Face magazine in February 1983[49] was described as "a Soho legend himself, straight out of Shaft, huge hats, fistfuls of rings and the only black man to own a venue in Soho." The publication also quoted his jeweller describing a mountainous ring he was making for the glamorous club owner: “18‑carat gold, 16 diamonds, it shone like a torch. I showed it to Vince and he said, I want more diamonds on it.” Howard spent some time trying to identify an audience, first with soul music, and then becoming a blatantly gay venue in those early days following liberation.

“A rather seedy gay club frequented by rough lesbians and even rougher trannies... It was owned by a 300-pound six-foot-four black convicted pimp named Vince who sported a huge black fedora, a long leather coat, and fingers the size of sausages with enough diamond rings to give Imelda Marcos cause for concern. And lest we forget, in those days Soho was not full of posh restaurants and membership clubs; it was a vice-infested square mile that housed a red light above every door and on every floor." – Chris Sullivan on Billy’s in his book, We Can Be Heroes (2012).[54]

Billy's changed its name to Gossip's[55] and became part of London's clubbing heritage by spawning scores of weekly club-nights that transformed Britain's music and fashion scene during the 1980s, crucially a Bowie night run by Steve Strange and Rusty Egan who teamed up at Billy's in 1978 and went on to open the hugely influential Blitz Club which kick-started the New Romantics movement.[56]

Reconstruction[edit]

During the 1970s, the ground floor at No 69 had been occupied by A. Stewart McCracken Ltd Auction Rooms[57] and at No 70 was the Hostaria Romana restaurant.[58][59] More recently, 69–70 Dean Street became a bar in The Pitcher and Piano chain[60][61][62] and the pair of houses became Listed Grade II. Then in the run-up to their rebirth in 2008, the interiors of numbers 69 and 70 were completely rebuilt[63] by Soho House to create the Dean Street Townhouse hotel and restaurant.[64][65]

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle's first date took place at the Dean Street Dining Room[66] in the Dean Street Townhouse in 2016.[67]

Notable members of Tennant's club[edit]

An extensive hand-written list of members is illustrated in Michael Luke's Gargoyle Years, between pages 84–85.[68]

- Fred Astaire[69]

- Francis Bacon (artist)[21]

- Hermione Baddeley[70]

- Tallulah Bankhead[21]

- Lady Caroline Blackwood

- Guy Burgess[21]

- Noël Coward[21][69]

- Lucian Freud[71]

- Graham Greene

- Augustus John[21]

- Robert Kee

- Donald Maclean[21]

- Henri Matisse

- John Minton[13]

- Lee Miller[22]

- Ivan Moffat

- Henrietta Moraes

- Dylan Thomas[21][72]

- Philip Toynbee

References[edit]

- ^ Luke, Michael (1991). David Tennant and the Gargoyle Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 2. ISBN 0-29781124X. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "A Tale of Two Houses". sohohome.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d "The Pitt Estate in Dean Street: Nos. 69 and 70 Dean Street – British History Online". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "History – Dean Street Townhouse". deanstreettownhouse.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Survey of London: Volumes 33 and 34, St Anne Soho. Originally published by London County Council, London, 1966.

- ^ Clarke, Mary Cowden (2 June 1864). "The life and labours of Vincent Novello". London, Novello & co. Retrieved 2 June 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hurd, Michael (1 March 1982). Vincent Novello—and company. Granada. ISBN 9780246117335. Retrieved 2 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cooper, VictoriaL (5 July 2017). The House of Novello: Practice and Policy of a Victorian Music Publisher, 1829?866. Routledge. ISBN 9781351543576. Retrieved 2 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Luke, Michael (1991). David Tennant and the Gargoyle Years. Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, pp21-23. ISBN 0-29781124X.

- ^ "Michael Luke". The Independent. 6 October 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Michael Luke". 11 April 2005.

- ^ "Michael Luke". Independent.co.uk. 6 October 2011.

- ^ a b Jot101 (10 February 2013). "Jot101: Gargoyle Club Members 1". jot101ok.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "EXHIBIT OF TWO MAJOR ACQUISITIONS 1949-04-05" (PDF). moma.org. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Henri Matisse. The Red Studio. Issy-les-Moulineaux, fall 1911 – MoMA". moma.org. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Studio, Quai Saint-Michel by Henri Matisse". phillipscollection.org. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "The more bohemian forerunner of The Groucho Club in London's Soho". wordpress.com. 4 December 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Are Guttorm Nordbø (25 October 2015). "Norsia Gargoyle Club". Retrieved 2 June 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Matisse at the Gargoyle". wordpress.com. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Luke, Michael (1991). David Tennant and the Gargoyle Years. Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, pp48-49. ISBN 0-29781124X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hoare, Philip (9 April 2005). "Michael Luke: Writer, film producer and dashing chronicler of the Gargoyle Club". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ a b c "Life After Dark: A History Of British Nightclubs". thequietus.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "The Red Studio". MoMA. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ "100 Years After the Armory Show". Phillips Collection, 1 August 2013.

- ^ Luke, Michael (1991). David Tennant and the Gargoyle Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 145. ISBN 0-29781124X. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Jackson, Stanley (1946). An Indiscreet Guide to Soho, 134pp. London: Muse Arts Limited. ASIN B0006AR9XA.

- ^ Sverrisson, Marcella Martinelli & Trausti Thor (22 February 2015). "Old Soho waits". wsimag.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Thurston Hopkins (1956). "People dancing at the Gargoyle Club in Soho, London. Original Publication: Picture Post – 8593 – I Am the Queen Of Soho". gettyimagesgallery.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Whitmore, Greg (12 April 2013). "Unsung hero of photography Thurston Hopkins turns 100". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Luke, Michael (1991). David Tennant and the Gargoyle Years. Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, p197. ISBN 0-29781124X.

- ^ Spicer, Andrew; McKenna, A. T. (24 October 2013). The Man Who Got Carter: Michael Klinger, Independent Production and the British Film Industry, 1960–1980. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857723093. Retrieved 2 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Jimmy Jacobs and the Nite Spots – Swingin' Soho". discogs. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Huntley Film Archives (9 July 2013). "Striptease club in Soho in the 1960s – Film 5132". Retrieved 2 June 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Archive film: 5132, 1960, Sound, B/W, Entertainment + Leisure". huntleyarchives.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Gallery: Nell Gwynne London Strip Club". reprobatemagazine.uk. 30 March 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ reviews of the top night clubs and strip joints in London 66 VOL. 6. No. 63 FEBRUARY, 1961

- ^ "Poker-faced millionaire – Sport – The Observer". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Miles, Barry (2011). London Calling: A Countercultural History of London since 1945. Atlantic Books: London, pp480.

- ^ "Sex and Power Working in a Strip Club". satpurusha.com. 2 August 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "The Avengers Declassified: Steed and Gale". declassified.hiddentigerbooks.co.uk. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Strippers and stand-up comics in the early days of British alternative comedy". wordpress.com. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "AP2588 – Gargoyle and Nell Gwynne Club, Soho (30x40cm Art Print)". retrocards.co.uk. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Club Soho Stock Photos and Pictures – Getty Images". gettyimages.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Latest News". Peter Rosengard website. Retrieved 07–04–18.

- ^ Double, Oliver (2005). Getting the joke the inner workings of stand-up comedy. London: Methuen. p. 38. ISBN 9781408155042. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ Johnson, David (1 January 1981). "Something Funny is Happening in Stripland". Over21, January issue, page 36, republished at Shapersofthe80s. London. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "How The Young Ones Changed Comedy". Gold.UKTV, producer Sean Doherty. 28 May 2018.

- ^ "A History of the 80s BATCAVE Scene! -". cvltnation.com. 14 June 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ a b Johnson, David (1 February 1983). "69 Dean Street: The Making of Club Culture". The Face, February 1983, issue 34, page 26, republished at Shapersofthe80s. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Peter gets serious about 9/11". jewishtelegraph.com. 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Miles, Barry (2011). London Calling: A Countercultural History of London since 1945. Atlantic Books: London, Chapter2.

- ^ Taylor, David (2018). "The Mandrake Club". henrybebop. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Luke, Michael (1991). David Tennant and the Gargoyle Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 187. ISBN 0-29781124X. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Graham Smith; Chris Sullivan. We Can be Heroes: Punks, Poseurs, Peacocks and People of a Particular Persuasion – page 48 (Unbound, 2012)

- ^ "Gossips Club, Billys, 69 Dean Street and Meard St, Soho, London, home of the Batcave, Alice in Wonderland, Gazzas Rocking Blues and more". urban75.org. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Johnson, David (4 October 2009). "Spandau Ballet, the Blitz Kids and the birth of the New Romantics". The Observer.

- ^ "I Love Dean Street, Soho – The Glittering Art of Soho". glitteringartofsoho.com. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Fox, Ilana (4 February 2016). The Glittering Art of Falling Apart. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 9781409122890. Retrieved 2 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "HOSTARIA ROMANA LIMITED, WC1H 9BQ 7–12 TAVISTOCK SQUARE Financial Information". CompaniesInTheUK. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Dean Street Townhouse, 69–71 Dean Street, London W1". The Independent. 2 January 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Pitcher and Piano – quality food and drink". 4 April 2003. Archived from the original on 4 April 2003. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Pitcher & Piano, London". whatpub.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Inside The Restaurant Where Prince Harry and Meghan Markle Had Their First Date – Architectural Digest". architecturaldigest.com. 28 December 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Mcdonald, Anna (14 April 2010). "Hotel Review: Dean Street Townhouse in London". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "Dean Street Townhouse". The Daily Telegraph. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Gerard, Jasper (23 April 2010). "London restaurant guide: Dean Street Dining Room, London W1". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Ryan, Lisa (16 April 2018). "Everything We Know About Meghan Markle and Prince Harry's First Date". thecut.com. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Luke, Michael (1991). David Tennant and the Gargoyle Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 84. ISBN 0-29781124X. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ a b Weinreb, Ben, ed. (2008). The London encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 233. ISBN 9781405049245. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ "Gargoyle Club Members 2 | Jot101". 11 February 2013.

- ^ "Gargoyle Club Members 1 | Jot101". 11 February 2013.

- ^ "Gargoyle Club Members 3 | Jot101". 12 February 2013.