Atragon

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Atragon | |

|---|---|

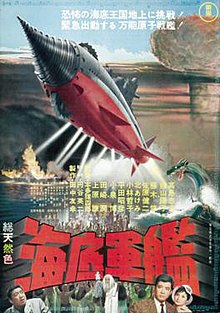

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ishirō Honda |

| Screenplay by | Shinichi Sekizawa[1] |

| Based on |

|

| Produced by | Tomoyuki Tanaka |

| Starring | Jun Tazaki Tadao Takashima Yōko Fujiyama Yū Fujiki |

| Cinematography | Hajime Koizumi |

| Edited by | Ryohei Fujii |

| Music by | Akira Ifukube |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release date | December 22, 1963 (Japan) |

Running time | 94 minutes[2] |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Box office | ¥175 million[3] |

Atragon (海底軍艦, Kaitei Gunkan, lit. 'The Undersea Warship') is a 1963 Japanese tokusatsu science fiction film directed by Ishirō Honda, with special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya. Produced and distributed by Toho, it is based on The Undersea Warship: A Fantastic Tale of Island Adventure by Shunrō Oshikawa and The Undersea Kingdom by Shigeru Komatsuzaki. The film stars Jun Tazaki, Tadao Takashima, Yōko Fujiyama, Yū Fujiki, and Ken Uehara.

The film was released in Japan on December 22, 1963, and in the United States in 1965 via American International Pictures. A two-episode anime OVA titled Super Atragon, based on the same novels, was produced by Phoenix Entertainment in 1995.

Plot[edit]

The legendary empire of the lost continent of Mu reappears to threaten the world with domination. While countries unite to resist, an isolated World War II captain has created the greatest warship ever seen, and possibly the surface world's only defense.

While on a magazine photo shoot one night, photographers Susumu and Yoshito witness a car drive into the ocean. While speaking with a detective the next day they spot Makoto Jinguji, daughter of deceased Imperial Captain Jinguji, who is also being followed by a suspicious character. Her father's former superior, retired Rear Admiral Kusumi is confronted by a peculiar reporter, who claims contrarily that Captain Jinguji is alive and at work on a new submarine project. The threads meet when a mysterious taxi driver attempts to abduct Makoto and the Admiral, claiming to be an agent of the drowned Mu Empire. Foiled by the pursuing photographers, he flees into the ocean.

During another visit to the detective, a package inscribed "MU" arrives for the Admiral. Contained within is a film depicting the thriving undersea continent (with its own geothermal "sun") and demanding that the surface world capitulate, and prevent Jinguji from completing his Atragon submarine, named Gotengo. The UN realizes that the Atragon may be the world's only defense and requests that Admiral Kusumi appeal to Jinguji. Concurrently, Makoto's stalker is arrested and discovered to be a naval officer under Jinguji. He agrees to lead the party to Jinguji's base but refuses to disclose its location. After several days of travel, the party find themselves on a tropical island inhabited only by Jinguji's forces and enclosing a vast underground dock.

Eventually Captain Jinguji greets the visitors, though he is cold toward his daughter and infuriated by Kusumi's appeal. He built Gotengo, he explains, as a means to restore the Empire of Japan after its defeat in World War II, and insists that it be used for no other purpose. Makoto runs off in anger, later to be consoled by Susumu. Gotengo's test run is a success, the heavily armored submarine even elevating out of the water and flying about the island. When the Captain approaches Makoto that evening they exchange harsh words; again Susumu reproaches the Captain for his selfish refusal to come to the world's aid. After Makoto and Susumu are kidnapped by the reporter, and the base crippled by a bomb, Jinguji consents to Kusumi's request and prepares Gotengo for war against Mu.

The Mu Empire executes a devastating attack on Tokyo and threatens to sacrifice its prisoners to the monstrous deity Manda if the Atragon appears. The submarine appears, pursuing a Mu submarine to the Empire's entrance in the ocean depths. Meanwhile, Susumu and the other prisoners escape their cell and kidnap the Empress of Mu. They are impeded by Manda, but soon rescued by Gotengo, which then engages the serpent and freezes it using the "Absolute Zero Cannon". Jinguji offers to hear peace terms, but the proud Empress refuses. The Captain then advances Gotengo into the heart of the Empire power room and freezes its geothermal machinery before successfully escaping to the surface. This results in a cataclysmic explosion visible even to those on deck of the surfaced submarine. Her empire dying, the Mu Empress abandons the Atragon and, Jinguji and company looking on, swims into the conflagration.

Cast[edit]

- Jun Tazaki as Captain Hachiro Jinguji

- Tadao Takashima as Susumu Hatanaka

- Yōko Fujiyama as Makoto Jinguji

- Ken Uehara as Rear Admiral Kusumi

- Yū Fujiki as Yoshito Nishibe

- Kenji Sahara as Umino

- Hiroshi Koizumi as Detective Ito

- Akihiko Hirata as Mu Agent #23

- Hideyo Amamoto as High Priest of Mu

- Tetsuko Kobayashi as Empress of Mu

Production[edit]

Writing[edit]

Atragon is loosely based on The Undersea Warship: A Fantastic Tale of Island Adventure (1899) by Shunrō Oshikawa and The Undersea Kingdom (1954-1955) by Shigeru Komatsuzaki.[4] Komatsuzaki also served as an uncredited designer for the film, as he had with The Mysterians and Battle in Outer Space.[3]

Shinichi Sekizawa submitted his first draft on August 10, 1963, following revisions and storyboards by Komatsuzaki. Sekizawa thought up the character of Jinguji after reading about the Brazilian-Japanese groups Machigumi and Kachigumi, one of which felt that Japan should have won World War II. He saw this as pointless fanaticism and wanted to embody this in the admiral whose nationalism blinds him.

Instead of a dragon, Manda was envisioned as a giant rattlesnake. There is some debate as to whether Manda was always in the script (a snake monster doesn’t appear in the Undersea Kingdom) or whether the beast was added at Tomoyuki Tanaka’s insistence like he did with Maguma in Gorath (1962). Manda’s design was changed to resemble a Chinese dragon due to 1964 being the Year of the Dragon, and this was Toho’s New Year’s blockbuster.[5]

Many of the film’s most memorable elements weren’t added until the final draft, which was finished by September 1963. This includes the Mu attack launched from Mt. Fuji, the earthquake assault on Marunochi in Tokyo, and the Gotengo’s zero cannon. Sekizawa also hoped that Captain Jinguji would be played by Toshiro Mifune, though he know his hopes were in vain as Mifune was too expensive and tended to decline offers for giant monster films.

Sekizawa originally wrote a scene in a late draft of the script where Jinguji learned of his daughter's kidnapping and was prepared to sacrifice her in order to save the world, which triggered an argument between Jinguji and Kosumi. This was cut by director Ishiro Honda because he saw the story as a parable of global problems rather than personal problems. The film was originally scheduled to show the Mu Empire also attacking New York City, but there wasn’t enough time due to the rushed shooting schedule. Another elaborate deleted scene is expressed in the film's storyboards and occurs as the characters arrive on Jinguji’s island. As they drive through the vast wasteland In the jeep, they are consumed by a black dust cloud. The jeep almost drives into a huge pit, with Makota saved by Susumu.

Filming[edit]

Shinichi Sekizawa originally wrote the character of Jinguji for Toshiro Mifune. However, no one approached the actor prior and by the time casting was underway Mifune was already tied up in rehearsals for what would be a 18 month shoot for Red Beard (1965).

Ishiro Honda had no idea whom to cast as the Empress of Mu but met Tetsuko Kobayashi by chance, who was working on a TV show in Toho's lot. Honda found her to be "hard working and very energetic." Kobayashi also applied the Empress' makeup herself.[3]

Over 70,000,000 yen was spent on the construction of sets and props for the film. By Toho standards, this was a large sum although less than recent productions such as Gorath (1962).

The film's production schedule was shorter than usual, with production beginning September 5, 1963, targeted for a December release of that same year. This resulted in effects director Eiji Tsuburaya scaling back some effects. Honda originally wanted to show towns and residual areas for the Mu Empire but did not have enough money in the budget.[3]

The film became the 13th highest grossing domestic film of the year, grossing 175 million yen.

Special effects[edit]

Five models of the Gotengo were built for the film with steel hulls for supporting their internal mechanisms. All at various scales, the largest was 4.5 meters (15 feet long), manufactured by an actual ship-building company for the price of 1,500,000 yen. This version was fully operational with wings, fins, gun turrets, the bridge, and the drill all movable by remote radio control devices built into the hull. This model was large enough for a technician to lie inside the hull and manually operate some of the ships movable parts. Other models of the Gotengo were built to lengths of 3 meters (1/50) scale, 2 meters (1/75) scale, 1-meter (1/150) scale, and 30 cm (1/500) scale. Altogether, two models of each of these scales were built except for the 30 cm version, of which five were built. The 30 cm model was used mainly in water tank shots to depict the Gotengo cruising on the surface of the sea. A small mechanical arm was attached to the ship beneath the water line, providing the ship mobility from outside the camera’s vantage point.

The film’s highlight is the trial run of the Gotengo. Using an indoor water tank with a miniature shore line placed in front of a huge curved backdrop painting, the scene was shot in three different cuts, each of which used a different scale miniature sub. The initial scene showing the Gotengo surfacing was done by Eiji Tsuburaya without any composition. The five-meter model was used to express the illusion of mass as the ship rises. From the water tank. The model was attached to an underwater crane that forced the ship through to the surface of the pool. High-speed photography was employed with the camera cranking at 10 times normal speed. As the ship began to fly, a two-meter model, suspended by wires, was also filmed at high speed. Air jets located at the bottom of the model created the illusion of upward propulsion. The final cut of the scene utilized a one-meter model to depict the Gotengo slowly flying forward in a long shot.

The scene where the American submarine Red Satan is crushed by water pressure was done by pumping air out of the model.

The largest set for the film was inside Toho’s Stage No. 11, then the largest on the back-lot. An elaborate backdrop measuring 30 feet high and 120 feet long was made for long shots of the Empress and her court overseeing the Mu ritual. The royal contingent, consisting mostly of the wives of American servicemen, was placed on a small platform with the pillars, balcony, and antechambers all painted in perspective on the backdrop. The chamber was filled with 600 male and female dancers were choreographed by Ishiro Honda to Akira Ifukube’s Mu ritual music.

The destruction of the Tokyo business district required that the Ginza and Marunouchi areas be reproduced in miniature at 1/20 scale. The buildings were made of plaster, and only a handful were made with internal steel structures, so that the buildings would partially survive the destruction. When the model was completed, stagehands crawled under the platform and partially cut though the main supports. Ropes were then tied to each support beam, and all the ropes were attached to the bumper of a truck. Tsuburaya’s vision of the scene was that the underground collapse would slowly ripple through the city, destroying it in a rolling wave. The destruction of the Ginza and Marunouchi districts did not go as planned. When time came for shooting, the technician who was driving the truck panicked and drove off too quickly, causing the entire model city to collapse at the same time. The staff all gasped, thinking the shot was ruined and that Tsuburaya would surly order the set rebuilt for another take. Tsuburaya stood silently for a while contemplating the situation, and finally he announced that he would take care of the matter in editing room.

The attack by the Mu submarine on Tokyo Bay was done in the huge 100-centimeter water tank located outdoors on the Toho backlot. Ten miniature tankers were constructed, each to a different scale, the maximum scale being 1/20 and the smallest 1/100. These ships were distributed in the water tank to create a forced perspective, adding greater depth to the scene than the confines of the tank would normally allow. Since the scene was shot with high-speed photography for more realism, a great amount of light was required for filming. Natural sunlight was sufficiently bright for filming only between 3:00PM and 4:00PM, so preparations were made from sunrise to ready the set for a tight afternoon shooting schedule. Six automatic remote-control cameras shot the scene simultaneously as six miniature ships exploded in sequence. Conventional animation was used to add the Mu subs ray to live action.

The aqualungs used by the Mu agents cost 70,000 yen each, with an additional charge of 100,000 yen to Toho for custom design of the suit. Altogether, 30 such aqualungs were built, and each was fully functional for underwater use.

The underwater sequences were achieved through camera filters and smoke machines.

The immense wall of smoke and flames which erupted from the explosion of the Mu power chamber was created using a small water tank against which a camera was secured upside down beneath the water line. A sky backdrop was placed behind the water, and colored paints were poured into the water, creating billowing, smoke-like clouds.

The mu submarines which were destroyed by the Gotengo’s freeze cannon were 2 cm models built to float upside down in the water tank. The ice flow in which the subs were trapped prior to their demise consisted of paraffin.

The scene where Shingugi’s strike team uses freeze ray guns on attacking Mu soldiers was done using matte paintings.

The underwater sequences were achieved through camera filters and smoke machines.

Release[edit]

Atragon was released in Japan on December 22, 1963. It became the 13th highest grossing domestic film of the year, grossing ¥175 million.[3]

Atragon became a popular feature on TV and at film festivals. In fact, it was so popular that it was re-released in 1968 as the support feature for Honda's Destroy All Monsters. It was also the 1964 Japanese entry at the Trieste Science Fiction Film Festival.[6]

American International Pictures afforded the film a successful US theatrical release in 1965, with minimal changes and quality dubbing by Titra Studios,[7] as a double feature with The Time Travelers.[8] The new name Atragon, derived from Toho's international title Atoragon, is presumably a contraction of "atomic dragon", a colorful moniker for the titular juggernaut; however, AIP's dubbed dialogue refers to the Goten-go by the name "Atragon". This shortening from four to three syllables was the choice of AIP, since several European markets released the film as Atoragon (Italy) and Ataragon (France). While Atragon became Toho's first tokusatsu eiga (visual effects film) released on home video in 1982, and though the film is exceptionally popular among western tokusatsu fans, Atragon was not released on home video in the United States until Media-Blasters' DVD in 2005 (although the film was in constant television syndication in the US until the early 1980s). Media Blasters had intended to use the original Titra Studios dubbing, but Toho forced the company to use its international version. This alternate dubbed version syncs up precisely with the Japanese video, but fans generally consider these international dubs to be inferior.

Other appearances[edit]

Manda later appeared in the 1968 Godzilla film Destroy All Monsters. Manda and the Gotengo, the original and an updated version, were featured in Godzilla: Final Wars.[9][10]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Galbraith IV 1998, p. 137.

- ^ 海底軍艦

- ^ a b c d e Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 204.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 201.

- ^ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 203.

- ^ Parish, James Robert and Michael R. Pitts. The Great Science Fiction Pictures.

- ^ Craig, Rob (2019). American International Pictures: A Comprehensive Filmography. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 43. ISBN 9781476666310.

- ^ Bogue, Michael. "Atragon at Nine. Memories of Toho's Live-Action Super-Sub Saga". G-Fan. 1 (66): 36.

- ^ Kalat 2010, p. 250.

- ^ Solomon 2017, p. 290.

Bibliography[edit]

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1998). Monsters Are Attacking Tokyo: The Incredible World of Japanese Fantasy Films. Feral House. ISBN 0922915474.

- Godziszewski, Ed (1995). "Atragon: A Toho Classic Revisited". G-Fan #21: 18–33.

- Kalat, David (2010). A Critical History and Filmography of Toho's Godzilla Series (2nd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 9780786447497.

- Parish, James Robert; Pitts, Michael R. (1977). The Great Science Fiction Pictures. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-1029-8.

- Ragone, August (2007). Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6078-9.

- Ryfle, Steve; Godziszewski, Ed (2017). Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 9780819570871.

- Solomon, Brian (2017). Godzilla FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the King of the Monsters. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 9781495045684.