Holland Nimmons McTyeire

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Holland Nimmons McTyeire | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 28, 1824 |

| Died | February 15, 1889 (aged 64) Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Randolph-Macon College |

| Occupation(s) | Preacher, educator |

| Spouse | Amelia Townsend |

| Relatives | John James Tigert III (son-in-law) John J. Tigert (grandson) |

| Signature | |

Holland Nimmons McTyeire (July 28, 1824 – February 15, 1889) was an American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, elected in 1866. He was a co-founder of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. He was a supporter of slavery in the United States.

Early life[edit]

Holland McTyeire was born on July 28, 1824, in Barnwell County, South Carolina[1][2][3] His parents; Capt. John McTyeire (1792–1859)[4] and Elizabeth Nimmons (1803–1861),[5] were both members of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. His father was "a cotton planter and a slaveholder."[6]

McTyeire attended the higher schools available at the time: first at Cokesbury, South Carolina, then Collinsworth Institute in Georgia. He graduated from Randolph-Macon College in Virginia (A.B. degree, 1844).[1][2][3]

Career[edit]

Already licensed to preach, McTyeire was admitted on trial into the Virginia Annual Conference in November 1845. He was appointed to Williamsburg, Virginia.[1] After one year's service, he was transferred to the Alabama Conference, admitted into full connection at the first of 1848.[3] He was a pastor in Alabama (Mobile and Demopolis) and Mississippi (Columbus), before transferring to the Louisiana Conference, where he was ordained elder in 1849.[1] He also was a pastor in New Orleans.[1]

In 1854, McTyeire was elected editor of the New Orleans Christian Advocate, serving in this position until 1858. He was then elected editor of the Nashville Christian Advocate, the central organ of the M.E. Church, South.[1][3] Interrupted in his editorial career by the American Civil War of 1861-1865, he entered the pastorate again in the Alabama Conference, serving in the city of Montgomery, from which he was elected to the episcopacy in 1866 at the General Conference meeting that year in New Orleans.[1]

McTyeire led a movement within the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, to establish "an institution of learning of the highest order."[2] In 1872, a charter for a "Central University" was issued to the bishop and fellow petitioners, who represented the nine M.E. Church, South Annual Conferences of the mid-south.[2] Their efforts failed, however, for lack of financial resources. Early in 1873, he went to New York City for medical treatment.[3] His wife, Amelia Townsend, was a cousin to Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt's second wife, Frank Armstrong Crawford Vanderbilt (1839–1885).[3][7] This connection led to Vanderbilt giving McTyeire two $500,000 (~$11.6 million in 2023) gifts, which the bishop used to found Vanderbilt University.[2][3][7] The Commodore's gift was given with the understanding that McTyeire would serve as chairman of the university's Board of Trust for life. He was appointed President of Vanderbilt University in 1873.[1]

McTyeire appointed Confederate veteran Fountain E. Pitts as the first pastor of the McKendree Church, later known as the West End United Methodist Church, in the early 1870s.[8]

Views on slavery[edit]

McTyeire "fully supported slavery as part of human nature."[9] In 1859, he published Duties of Christian Masters, where he opined that slavery was "God’s punishment and that he, as a follower of the faith, was bound to do all in his power to ensure this continued."[9]

Personal life[edit]

McTyeire was married to Amelia Townsend of Mobile, Alabama.[2][3]

Death and legacy[edit]

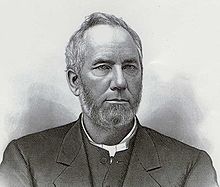

McTyeire died on February 15, 1889, in Nashville, Tennessee.[1] His portrait, done by Jared Bradley Flagg, hung in Main Hall (later known as Kirkland Hall) until it was destroyed by the 1905 fire.[3] Another portrait, done by Ella Sophonisba Hergesheimer in 1907, hangs in Kirkland Hall.[3]

In the 1940s, the first women's dormitory on the Vanderbilt campus was named McTyeire Hall; it was later renamed McTyeire International House.[3][10] Meanwhile, the McTyeire School for Girls, founded by Young John Allen and Laura Askew Haygood in Shanghai, China, is also named in his honor.

Bibliography[edit]

- Duties of Masters to Servants: Three Premium Essays (co-authored with C. F. Sturgis and A.T. Holmes; Charleston, South Carolina: Southern Baptist Publication Society, 1851).[11]

- A Catechism on Church Government (1869)

- A Catechism on Bible History (1869)

- Manual of the Discipline (1870)

- History of Methodism (1884)

- Passing Through the Gates (1889)

Further reading[edit]

- Fitzgerald, O.P., Holland N. McTyeire. Nashville, 1896.

- Bishop McTyeire's "Memorial Sketch" in the Conference Minutes of the M.E. Church, South General Conference of 1890, pp. 76–78.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "McTyeire, Holland Nimmons", in The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Samuel Macauley Jackson, ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1954, p. 120 [1]

- ^ a b c d e f Miletich, Patricia. "Holland N. McTyeire". The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society and the University of Tennessee Press. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Tennessee Portrait Project". Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ "Capt. John McTyeire". Geni. 14 December 1795.

- ^ "Elizabeth McTyeire". Geni. 20 August 1803.

- ^ McTyeire, H.N., Sturgis, C.F., Holmes, A.T., Duties of Masters to Servants: Three Premium Essays, Charleston, South Carolina: Southern Baptist Publication Society, 1851, p. 5

- ^ a b History of Vanderbilt University

- ^ "History". West End United Methodist Church. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Fuselier, Kathryn; Yee, Robert (October 17, 2016). "The Legacy of Slavery at Vanderbilt: Our Forgotten Past". Vanderbilt Historical Review. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ Vanderbilt University: McTyeire International House

- ^ McTyeire, H.N.; Sturgis, C.F.; Holmes, A.T. (1851). "Duties of Masters to Servants: Three Premium Essays". Archive.org. Charleston, South Carolina: Southern Baptist Publication Society. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)