Hot-blooded horse

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

A hot-blooded horse is an unscientific term from the field of horse breeding, coined by orientalists and popularized by various hippologists. It refers to a light horse with a lively temperament, primarily the oriental horse breeds of North Africa, the Near East and Central Asia. Such a name is also applied to some horse breeds descended from horses from these geographical regions, such as the Thoroughbred, Anglo-Arabian, and Namib horse.

In the French language, the expression cheval à sang chaud (hot-blooded horse) comes from a class conflict between the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy, from the end of the 18th century. In this context, great importance is given to the genealogy and the "purity" of the animals' blood. The Polish aristocrat and orientalist Wenceslas Severin Rzewuski established a classification of horses by blood temperature in his notes from a trip to the Arabian Najd, from 1817 to 1819. He classifies the Arabian and the Thoroughbred among the breeds with the hottest blood. In reality, horses of all breeds are warm-blooded mammals and have the same body temperature. The notion of a "hot-blooded" horse is nevertheless taken up in later hippological writings, and remains in use today.

Hot-blooded horses are saddle and sport animals, known for their liveliness, finesse, and emotional nature. A positive value judgment often accompanies this concept of a "blood" horse. It is used, in particular, in art and in the spread of hippophagy, as it is said that the qualities of the animal are supposed to be transmitted to human beings.

Definition and terminology[edit]

Horse breeds are usually classified by temperament [1][2] groups in a rather arbitrary way.[3] The French ethnologist Bernadette Lizet describes this concept of blood as "rich and polysemous".[4] The expression "hot-blooded",[5] which corresponds to French sang chaud, German warmblut and Spanish caballo de sangre /caliente,[6] comes from a classification of horse breeds by blood temperature established by the Polish orientalist Wenceslas Séverin Rzewuski at the beginning of the 19th century.[7] The homeothermy (the zoological concept of hot or cold-blood) of the horse is in fact the same, whatever its breed or origin, 37.5 to 38.5 °C,[8] but this concept of "hot-blood" has remained in the hippological field.[7]

In French, there are three blood groups used to classify horses: sang chaud (hot-blooded horse), sang froid (cold-blooded horse), and demi-sang (warm-blooded horse), which is the result of crossing the two previous groups.[2] The Thoroughbred horse is sometimes classified separately.[3] The concept of hot-blooded should not be confused with that of warmblood, which refers to sport horses originating from crosses between local cold-blooded strains and hot-blooded horses.[9]

The use of the concept of "blood" involves notions of breed, but also temperament.[2] "Close to the blood" is a rather vague breeding term, which does not correspond to any biological or zoological concept.[10] The more nervous, lively and easily heated a horse is, the more likely it is to be described as "close to the blood"; conversely, a horse that is heavy or not very lively will be described as "lacking in blood".[2] The term often refers to horses that are very similar to Thoroughbreds[2][10] or Arabian.[10][11] It can also refer to any horse that has been crossed with the Arabian.[6]

The "blood" is invoked in many concepts and popular expressions of equine breeding,[2] with a strong sociological dimension. In particular, Bernadette Lizet points out the construction of the notion of sang sous la masse, invoked to describe lively draft horses, and "ennoble" them in the eyes of their buyers and users.[12] This notion of "blood" also appears in the crossing of breeds. In France, the expression toucher au sang means crossing a blood horse with a grade horse to produce a Bidet horse or a half-blood.[13] The so-called "blood parent" is usually an Arabian, Thoroughbred or Anglo-Arabian horse with an equine ID.[14]

Breeds classified as "hot-blooded"[edit]

According to the 2016 edition of the zootechnical book edited by Valerie Porter for CAB International, the term hot-blooded is reserved in its strictest sense for the Arabian, Barb and Turk.[1] In an extended sense, it happens to include the major Iberian breeds, the Purebred Spanish and the Lusitano.[1] Dr. Gus Cothran, from the University of Kentucky, classifies separately the Iberian horses and the hot-blooded ones.[15] The Iberian horses are a cross between the hot-blooded Arabian and Barbed horses and the local cold-blooded Celtiberian strain.[16]

Dr. Veterinarian Kristin J. Holtgrew-Bohling's glossary (second edition 2014) describes "hot-blooded horses" as animals whose pedigree can be traced back to horses originating in the deserts of North Africa and the Mediterranean Sea, and this author broadly includes breeds, such as the Thoroughbred, Standardbred, Quarter Horse, and Tennessee Walker.[17][dubious ] This is the case for the Karabakh,[18] the Anglo-Arabian,[19] the Hanoverian and the Mecklenburger horse in Germany.[20] [dubious ] The Namib horse was described as hot-blooded, before a genetic study demonstrated its proximity to the Arabian.[21]

Origins[edit]

The question of the oldest ancestor of hot-blooded horses has been much debated. Wenceslas Severin Rzewuskiv considered the "Najdi Kocheilan" as the "superior because primordial" hot-blooded horse, a creation of God and Nature.[7] Lady Anne Blunt theorized that the hot-blooded horse, or Oriental horse, may represent a subspecies in its own right prior to the domestication of the horse, and may be the origin of all other breeds described as "hot-blooded" including the Arabian.[22]

In 1978, Colonel Denis Bogros described the Arabian breed as "the first blood horse",[23] a view shared by Laetitia Bataille.[10] In 1998, Louise Firouz presented the Caspian, a miniature horse from northern Iran, at a conference in Ashgabat as the oldest known hot-blooded horse, based on the genetic studies of Dr. Gus Cothran.[24] The idea that all hot-blooded breeds come from Central Asia has been discussed, but the extensive and early genetic admixture between equine populations makes it impossible to distinguish genetically between hot-blooded and cold-blooded breeds, as both branches originated in the same geographical region,[10] Central Asia, corresponding to the region of horse domestication.[25]

History of the concept[edit]

According to the ethnologist Bernadette Lizet, the concept of "blood" in the horse is part of an ideological battle between the bourgeoisie, which uses the draft horse and the Thoroughbred, and the aristocracy, which uses the Arabian saddle horse, which seeks "purity" and lines qualified as "blood". This conflict, mixing equine aesthetics and class conflict,[26] had its origins in the 1760s, when quarrels broke out between supporters of the Arabian horse and supporters of the Thoroughbred, at a time when equine breeding was dominated by the "tyranny of aristocratic linkings”.[27] Great importance was attached to the genealogical ancestry of horses, while the saddle horse was increasingly considered anachronistic.[13] Lizet describes the 19th century as "the century of the overbidding on the 'blood' of horses", through the increasing search for speed on the part of their breeders and users, who felt threatened by the "transport revolution", in the midst of industrialization.[13]

"Blood is the first characteristic of horses". —Ernest Aleo[28]

Lizet analyzes that situation as a "war of races and aesthetic codes, which, at the end of a final race for power, throws two classes and two ideological systems into a hand-to-hand combat with the animal".[13][29] In this context, many horses were given prestigious Arab ancestors.[13] The Haras Nationaux Français (French national stud farms) called upon agronomy for the "improvement" of equine breeds.[27] Frequent value judgments advocate the introduction of "blood" to "improve" peasant draft horses.[26] Thus, the hippologist Eugène Gayot (1850) praised the qualities of the blood horse, in a "fantasy of a return to the horse of the origins, this horse irrigated by the superior 'blood' ".[30] The American export market was a determining factor in the triumph of the notion of "blood under the mace", used to describe the draft horse.[31]

Wenceslas Séverin Rzewuski's travel notes[edit]

Wenceslas Séverin Rzewuski was a Polish orientalist aristocrat and polyglot who went on an expedition to the Bedouins of the Arabian Najd from 1817 to 1819. His treatise (written in French) proposes a "table of gradation of the blood of horses" and analyzes the "affection of the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula for horses" in order to judge the quality of their "blood", in other words, the value of the breed.[7] At that time, the Arabian horse enjoyed great popularity throughout Europe; Rzewuski also shared the idea of the superiority of the Arabian horse with Buffon, who had mentioned it in his work Histoire Naturelle.[7] Rzewuski writes in his notes that "The heat of the blood of the Arabian horse is I believe 50 degrees [...] That of the purebred Polish horse must be from 27 to 30".[32] He establishes a classification of horse breeds by blood temperature. According to him, the breed "all blood and fire", the hottest, is that of the "Bedouin Najdi Kocheilan of the deserts of Schamalieh and Hediazet", with a temperature of 80 degrees.[33] He then ranks, at 70 degrees, the Kocheilan and the Thoroughbred, which he calls "English horse of the high breed", or BloodHorse, in his notes.[7] He relates this supposed temperature of the horses' blood to the climate of the region where they are bred, believing that regions with a hot, dry climate produce the best horses:[7] "In such a dry climate, the breed and the strength of the blood often make up for the imperfections of the construction".[34] He defines the breed by controlling the genealogy and by the climate.[7] He naturally placed the horses that he imported and raised himself in his stud farms at the top of the blood classification that he had established.[7]

Other hippological sources[edit]

Aristide Houdaille's Traité sur la connaissance et la conservation du cheval (1836), specifies that "usage has established the expressions blood horses, thoroughbred and first blood horses, and half-blood horses”. He adds that the expression "blood horses" has been applied to all individuals who are part of the Thoroughbred breed.[35] According to him, this notion comes from the formation of the Thoroughbred breed in England, because "after a certain number of consecutive crossings, it was noticed that there was no more improvement and it was imagined from then on that the new breed had reached its highest point of perfection, and it was agreed to call all the horses that made it up pure or of first blood".[35]

In his work Hippognosie (1883), Honoré Pinel classified animals according to the color of their blood: "white blood" animals, insects and crustaceans, were said to be "cold blood", while "red blood" animals (such as humans and horses) were, according to him, "hot blood".[36] In Germany, at the same time, it was customary to distinguish the Warmblûtig (Edel), or noble hot-blooded horse, from the Englische vollblut (English Thoroughbred).[37] In 1885, a study of Canadian horses argued that they lacked the "warm blood of the racehorse".[38]

Louis Champion (1898) described the "blood horse" as "the purebred horse, the regenerative type",[39] and a little further on as a "horse which, without being purebred, is fairly close to it",[40] specifying that this blood horse was bred, at the time, in Normandy, Brittany, the Vendée and the Charentes.[41]

In 1907, a report of the American genetics association assimilated the notion of hot blood to that of oriental horse.[42] The use of this expression is reported in the 1930s in Portland: the classic example of "hot blooded horse" cited is the Arabian.[43] The 1924 Czechoslovakian Encyclopedia compares the merits of the hot-blooded horse to those of the cold-blooded horse.[44] In 1934, the proceedings of the International Congress of Agriculture stated that "the hot-blooded horse, with its stronger caliber, is better suited for industrial transportation purposes than the cold-blooded horse" because of its "greater vivacity and resistance".[45]

Characteristics[edit]

Hot-blooded horses are known for their qualities of speed, endurance, refinement, and nervous temperament, as opposed to the characteristics of the cold-blooded horse.[2][42] Bernadette Lizet notes the emphasis on "dryness of the skeleton and musculature - the head especially, thin and tiny", and the "sobriety of the hair system".[13] They are generally finer-boned than cold-blooded horses and are adapted to the saddle.[6] The majority of blood horses are also saddle horses[46] and sport horses:[10] for Louis Champion, "a saddle horse must have blood".[47] Because of their energy, they are not suitable for all riders.[48] They are more emotional, more sensitive to stress,[2] and can easily panic.[49] Their possible reactivity requires a "deft and vigorous" rider.[50]

These hot-blooded horses are generally selected for equestrian sports. For example, in Belgium in 1969, "rural equestrian sport and the breeding of hot-blooded horses form an indissoluble whole".[51] They are suitable for equestrian sports such as eventing, a discipline in which Thoroughbreds and Anglo-Arabs are valued. Half-bloods or warmbloods are generally preferred in dressage and show jumping. In the latter discipline, hot-bloods can be an advantage in obtaining responsiveness from the mount, but a warmblood horse is generally not the most suitable.[52]

In culture[edit]

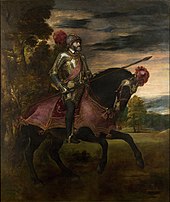

Hot-blooded horses are the subject of artistic representations. One interpretation of Titian's Equestrian Portrait of Charles V in Mühlberg argues that the symbolic representation of the horse, of Iberian model, is intended to emphasize the control of the (Spanish) human being over this horse coming from hot-blooded strains from the Maghreb.[16]

Symbolically, this notion of the "blood horse" has been used in the promotion of hippophagy in France since the 19th century.[13] Horse meat is presented as "blood", an object of superiority and food hygiene.[13] The horse highlighted on the signs of horse butcheries is a "fine steed", reminiscent of the Arabian horse.[13] The meat of the Thoroughbred, and more generally of the "blood" horse, is presented as a butcher's ideal, with a more pronounced red color.[53]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Porter (2016, p. 426)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gillet (2012, p. 122)

- ^ a b Spindler, A. (1933). Le cheval à l'époque du moteur: production, mise en valeur, utilisation, les éléments du succès (in French). Berger-Levrault. pp. 30, 224.

- ^ Lizet, Bernadette (1996). Champ de blé, champ de course : Nouveaux usages du cheval de trait en Europe. Bibliothèque équestre (in French). Jean-Michel Place. p. 324. ISBN 2-85893-284-0.

- ^ Jones (1971, p. 189)

- ^ a b c Boulet, Jean-Claude (2002). Dictionnaire multilingue du cheval (in French). JC Boulet. p. 527. ISBN 2980460060.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lizet, Bernadette (2004). "Le cheval arabe du Nejd et le système des races orientales dans le manuscrit de Wenceslas Severyn Rzewuski" (PDF). Anthropozoologica (in French). 39 (1): 79–97.

- ^ Institut du cheval (1994). Maladies des chevaux (in French). France Agricole Editions. p. 279. ISBN 2855570107.

- ^ Rovere, Gabriel (2016). Sport horses: breeding specialist from a single breeding programme?. Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark and Wageningen University. p. 11. ISBN 978-94-6257-635-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Bataille & Tsaag (2017, p. 3)

- ^ Edwards, Elwyn (2006). Les Chevaux. Pratique (in French). Romagnat: De Borée. p. 272. ISBN 2844944493.

- ^ Lizet (1988)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lizet (1988, p. 8,22)

- ^ Lizet (1996, p. 320)

- ^ "Steens Mountain Kiger Registry Cothran Report". KIGERS. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ a b Jardine, Lisa; Brotton, Jerry (2005). Global Interests: Renaissance Art Between East and West. Reaktion Books. p. 224. ISBN 1861895496.

- ^ Holtgrew-Bohling, Kristin J. (2014). Large Animal Clinical Procedures for Veterinary Technicians (2nd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 584. ISBN 978-0323290357.

- ^ McBane, Susan (2004). Horse & pony breeds. Barnes & Noble. p. 224. ISBN 0760762279.

- ^ McBane (2004, p. 96)

- ^ Champion (1898, p. 55)

- ^ Cothran, E.G.; Van Dyk, E.; Van der Merwe, F.J. (1 March 2001). "Genetic variation in the feral horses of the Namib Desert, Namibia". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 72 (1): 18–22. doi:10.4102/jsava.v72i1.603. ISSN 1019-9128. PMID 11563711.

- ^ Jones, William (1986). "Genetic recreation of wild horses". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 6 (5): 246–249. doi:10.1016/s0737-0806(86)80050-8 – via Elsevier.

- ^ Bogros, Denis (1978). L'Arabe, premier cheval de sang. Crépin-Leblond. p. 311.

- ^ Firouz, Louise (1998). The original ancestors of the Turkoman, Caspian horses (PDF). Ashgabat.

- ^ Bataille & Tsaag (2017, p. 12)

- ^ a b Lizet (2015, p. 101)

- ^ a b Anthropozoologica. L'Homme et l'animal, Société de recherche interdisciplinaire. 2008. pp. 97–99.

- ^ "Journal des haras des chasses et des courses de chevaux, recueil périodique consacre a l'étude du cheval, a son éducation (etc.)". Bureau du Journal. 50: 160. 1851.

- ^ Lizet (2015, p. 248)

- ^ Lizet (2015, p. 100)

- ^ Lizet (2015, p. 103)

- ^ Rzewuski (2002, p. 450)

- ^ Rzewuski (2002, p. 628)

- ^ Rzewuski (2002, p. 456)

- ^ a b Houdaille, Aristide (1836). Traité sur la connaissance et la conservation du cheval ; ou, Cours d'hippiatrique à l'usage des écoles d'artillerie (in French). Verronnais. pp. 191–193.

- ^ Pinel, Honoré (1883). Hippognosie ou Connaissance complète du cheval (in French). L. Baudoin. pp. 42, 447.

- ^ Lavalard, E. (1894). "Le cheval". Librairie de Firmin-Didot (in French). 2: 344.

- ^ "Le journal d'agriculture illustre". Département de l'Agriculture de la Province de Québec. 8–11: 150. 1885.

- ^ Champion (1898, p. 19)

- ^ Champion (1898, p. 47)

- ^ Champion (1898, p. 48)

- ^ a b Report, vol. 3, American Genetic Association, 1907, p. 44

- ^ Cumming, William (1984). Sketchbook: A Memoir of the 1930s and the Northwest School. University of Washington Press. p. 239. ISBN 0295985607.

- ^ Ruml, Bohuslav; Butter, Oskar (1828). Encyclopédie tchécoslovaque (in French). Vol. 3. Bossard. pp. 462–468.

- ^ Congrès international d'agriculture (1934). Actes (in French). p. 278.

- ^ Champion (1898, p. 23)

- ^ Champion (1898, p. 22)

- ^ Racic-Hamitouche, Françoise; Ribaud, Sophie (2007). Cheval & équitation (in French). Editions Artemis. p. 287. ISBN 978-2844164681.

- ^ Deutsch, Julie (2006). Le comportement du cheval. Les Équiguides (in French). Éditions Artemis. p. 127. ISBN 2844166407.

- ^ Champion (1898, p. 53)

- ^ Ministère de l'agriculture. Service de l'information, Belgique. Administration des services économiques (1969). "Revue de l'agriculture". Ministère de l'Agriculture de Belgique (in French): 1055.

- ^ Steinkraus, William (2012). Reflections on Riding and Jumping: Winning Techniques for Serious Riders. Trafalgar Square Books. p. 240. ISBN 978-1570766022.

- ^ Lizet, Bernadette (2010). "Le cheval français en morceaux. Statut de l'animal, statut de sa viande". Anthropozoologica. 45 (1): 137–148. doi:10.5252/az2010n1a9. S2CID 161855125.

Sources[edit]

- Bataille, Laetitia; Tsaag, Amélie (2017). Races équines de France (in French) (2nd ed.). Paris: Éditions France Agricole. ISBN 978-2-85557-481-3. OCLC 971243118.

- Champion, Louis (1898). Du cheval de selle français, ce qu'il est, ce qu'il pourrait être (in French). Paris: J. Rothschild.

- Gillet, Émilie (2012). Mini-Dico Français/Cheval, Cheval/Français. Larousse attitude - Animaux (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2035871947.

- Jones, William (1971). Genetics and Horse Breeding. Lea & Febiger. ISBN 0812107217.

- Lizet, Bernadette (1988). "Le " sang sous la masse "". Terrain (in French) (10). Terrain. Anthropologie & sciences humaines: 8–22. doi:10.4000/terrain.2925. ISSN 0760-5668.

- Lizet, Bernadette (2015). La bête noire: À la recherche du cheval parfait. Ethnologie de la France (in French) (1st ed.). Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. ISBN 978-2735118052.

- Porter, Valerie; Alderson, Lawrence; Hall, Stephen; Sponenberg, Dan (2016). Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding (6th ed.). CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-466-8.

- Rzewuski, Wenceslas (2002). Impressions d'Orient et d'Arabie. Un cavalier polonais chez les Bédouins (in French). Paris: José Corti-Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. ISBN 2714307973.

Further reading[edit]

- Serrano, V. (1997). "Horses of hot blood in the European Union". Congresos y Jornadas - Junta de Andalucia (Espana).