Jameh Mosque of Varamin

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Grand Mosque of Varamin | |

|---|---|

مسجد جامع ورامین | |

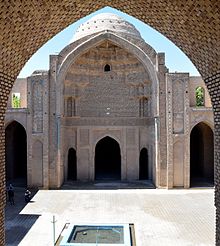

View from the room above the entrance | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Province | Tehran Province |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | In use occasionally. |

| Location | |

| Location | Varamin, Tehran, Iran |

| Geographic coordinates | 35°19′N 51°39′E / 35.32°N 51.65°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Ali Qazvini |

| Completed | 1322 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 66 meters |

| Width | 43 meters |

Jāmeh Mosque of Varāmīn (Persian: مسجد جامع ورامین Masjed-e-Jāme-e Varāmīn), Congregation mosque of Varamin, Friday mosque of Varamin or Grand mosque of Varamin is the grand congregational mosque (jāmeh) of Varamin in the Tehran Province of Iran. This mosque is one of the oldest buildings of Varamin city. Its construction began during the reign of Sultan Mohammad Khodabaneh and was completed during his son’s, Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, rule in 1322.[1] This building consists of a shabestan, portico, large brick dome, the structure beside shabestan and ten small arches along with one large arch in the middle.[2][3]

Architecture[edit]

The plan of the building is a rectangle measuring about 66 meters by 43 meters. [4] Nowadays, the mosque is located in the middle of an urban square. It has a rectangular plan and no other building is attached to it. Three exterior walls have a designed facade, but not the south-front. [5] The mosque has a four-iwan plan and includes an entrance in the north, a shabestan in the south, porches in the east and west. Mohammad Karim Pirnia categorizes building as Azeri style of architecture. [6] The entrance to the mosque is tall and elongated, similar to other Ilkhanid buildings and is decorated with intricate tiles. [7] The dome of the mosque is a square room measuring 10.5 by 10.5 meters,[4] which elevates in an octagonal shape, then a hexagon, and finally a dome with the help of squinches. The dome, the walls, even the squinches[8] are decorated with bricks, tiles and plaster. [7] Pirnia believes that the dome has two shells and the upper shell has been destroyed and only the lower shell remains. [6]The eastern porch which is an auxiliary entrance compared to the main entrance. The western porch, however, has no entrance and consists of two rows of columns. This portico was completely destroyed and has been rebuilt during the contemporary restorations of the building. [5]

(Inscription on the eastern porch: "Work of Ali Qazvini, May his God forgives him")

History and restorations[edit]

In the sixth century A.H., the family of Abu Sa'd Varamini, a wealthy Shia family from that era, built a mosque in Varamin, but the current building was built in 722 A.H. (1322 CE) by the order of Izz al-Din al-Quhadhi. Apparently, the mosque was damaged due to a disaster, and in the ninth century A.H. (15th century CE), Amir Yusef Khajeh ordered the building to be restored. After that, it was not maintained for 500 years. [5] For instance, Jane Dieulafoy, who visited the mosque during the Qajar period, wrote that no one prays there as peasants are afraid if the dome collapses and 'infidel foreigners' can watch it without any restrictions. [9] This mosque was registered in Iran's national list of heritage buildings in 1932 CE and its current boundaries were defined. It was excavated by archaeologists in 1960s and 1970s and was restored in the 80s.[5]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan (1994). The art and architecture of Islam 1250-1800. New Haven [Conn.]: Yale University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0300058888.

- ^ "Masjed-e Jame of Varamin". Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Friday Mosque of Varamin". Archived from the original on 2010-11-19. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ a b Amini, Mohammad; Rezvan, Homayun (2003). Tarikh-e Ejtemai-e Varamin (in Persian). Tehran: Elmi Farhangi Saheb-az-zaman. p. 132. ISBN 9640612278.

- ^ a b c d Nakhaī, Ḥusayn (2018). Masjid Jāmiʻ-i Varāmīn : bāzʹshināsī-i ravand-i shiklʹgīrī va sayr-i taḥavvul (in Persian) (Chāp-i 1 ed.). Tihrān: Rowzani. p. 69. ISBN 9789643348861.

- ^ a b Pīrnīyā, Muḥammad Karīm. (2005). Sabkšināsī-i miʻmārī-i īrānī (in Persian) (Čāp-i 4 ed.). Tihrān: Surūš-i Dāniš. ISBN 9649611320.

- ^ a b Kiyānī, Muḥammad Yūsuf (2004). Tārīkh-i hunar-i miʻmārī-i Īrān dar dawrah-ʼi Islāmī (in Persian) (Chāp-i 6 ed.). Tihrān: Sāzmān-i Muṭālaʻah va Tadvīn-i Kutub-i ʻUlūm-i Insānī-i Dānishgāhhā. p. 70. ISBN 9789644591228.

- ^ Islam: art and architecture (Special ed.). Germany: H.F. Ullman. 2007. p. 394. ISBN 9783848008384.

- ^ Dieulafoy, Jane. La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane (in French). ISBN 2012875467.