Kelly Miller (scientist)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

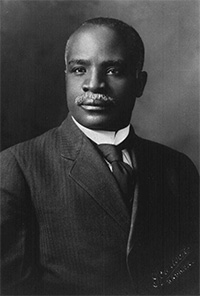

Kelly Miller | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 18, 1863 |

| Died | December 29, 1939 (aged 76) |

| Resting place | Lincoln Memorial Cemetery |

| Occupation(s) | mathematician, sociologist, essayist, newspaper columnist and author |

Kelly Miller (July 18, 1863 – December 29, 1939) was an American mathematician, sociologist, essayist, newspaper columnist, author, and an important figure in the intellectual life of black America for close to half a century. He was known as "the Bard of the Potomac".[1]

Early life and education[edit]

Kelly Miller was the third of six children born to Elizabeth Miller and Kelly Miller Sr. His mother was a former slave and his father was a freed black man who was conscripted into the Winnsboro Regiment of the Confederate Army. Miller was born in Winnsboro, South Carolina, where he would attend local primary and grade school.

From 1878 to 1880, Miller attended the Fairfield Institute.[2] Based on his achievements, he was offered a scholarship to Howard University, a historically black college. Miller finished the preparatory department's three-year curriculum in Latin and Greek, then mathematics, in two years. After finishing one department, he quickly moved on to the next one. Miller attended the College Department at Howard from 1882 to 1886.

In 1886, Miller was given the opportunity to study advanced mathematics with Captain Edgar Frisby. Frisby was an English mathematician working at the US Naval Observatory. Frisby's assistant, Simon Newcomb, noticed Miller's intellectual ability and recommended that he study at Johns Hopkins University. Miller spent the following two years at Johns Hopkins University (1887-1889) and became the first African-American student to attend the university. Miller studied mathematics, physics, and astronomy.[3] He was the first African American to study graduate mathematics in the United States.[4]

Miller was an honorary member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.[5]

Career[edit]

Unable to continue attending Johns Hopkins University due to financial limitations, Miller taught mathematics at the M Street High School in Washington, D.C. from 1889 to 1890. Appointed professor of mathematics at Howard in 1890, Miller introduced sociology (the development, structure, and functioning of human society) into the curriculum in 1895, serving as professor of sociology from 1895 to 1934. Miller graduated from Howard University School of Law in 1903.[6] In 1907, Miller was appointed dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.[6]

His deanship lasted twelve years, and in that time, the college changed significantly. The old classical curriculum was modernized and new courses in the natural sciences and the social sciences were added. Miller was an avid supporter of Howard University and actively recruited students to the school. In 1914, he planned a Negro-American Museum and Library. He persuaded Jesse E. Moorland to donate his large private library on blacks in Africa and the United States to Howard University and it became the foundation for his Negro-Americana Museum and Library center.[3]

He was a participant in the March 5, 1897 meeting to celebrate the memory of Frederick Douglass, which founded the American Negro Academy led by Alexander Crummell.[7] Until the organization was discontinued in 1928, Miller remained one of the most active members of this first major African American learned society, refuting racist scholarship, promoting black claims to individual, social, and political equality, and publishing early histories and sociological studies of African American life.[8]

Miller gained his well-known national importance from his involvement in another movement led by W. E. B. Du Bois. He showed intellectual leadership during the conflict between the "accommodations" of Booker T. Washington and the "radicalism" of the growing civil rights. Miller was known in two ways to the public.

On African-American education policy, Miller aligned himself with neither the "radicals" — Du Bois and the Niagara Movement — nor the "conservatives" — the followers of Booker T. Washington.[citation needed] Miller sought a middle way, a comprehensive education system that would provide for "symmetrical development" of African-American citizens by offering both vocational and intellectual instruction.[9]

In February 1924, Miller was elected chairman of the Negro Sanhedrin, a civil rights conference held in Chicago that brought together representatives of 61 African-American organizations to forge closer ties and attempt to craft a common program for social and political reform.[10]

He believed that blacks should favor free market rather than government or union power, stating:

The capitalist has but one dominating motive, the production and sale of goods. The race or color of the producer counts but little.... The capitalist stands for an open shop which gives to every man the unhindered right to work according to his ability and skill. In this proposition the capitalist and the Negro are as one.[11]

He was critical of racially biased policing, saying in 1935 that police violence harmed community trust: "Too often the policeman's club is the only instrument of the law with which the Negro comes into contact. This engenders in him a distrust and resentful attitude toward all public authorities and law officers".[12]

Written works[edit]

Miller was a prolific writer of articles and essays which were published in major newspapers, magazines, and several books, including Out of the House of Bondage. Miller assisted W. E. B. Du Bois in editing The Crisis, the official journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[6] Miller started off publishing his articles anonymously in the Boston Transcript. He wrote about both radical and conservative groups. Miller also shared his views in the Educational Review, Dial, Education, and the Journal of Social Science. His anonymous articles later became subject for his lead essay in his book Race Adjustment published in 1908. Miller suggested that African Americans had the right to protest against the unjust circumstances that came with the rise of white supremacy in the South. Miller supported racial harmony, thrift, and institution building.[3]

In 1917, Miller published an open letter to President Woodrow Wilson in the Baltimore Afro-American against lynching, which he called "national in its range and scope," and called the government's failure to stop it "the disgrace of democracy."[13] He also stated "It is but hollow mockery of the Negro when he is beaten and bruised in all parts of the nation and flees to the national government for asylum, to be denied relief on the basis of doubtful jurisdiction. The black man asks for protection and is given a theory of government."[3]

It was circulated as a pamphlet in the camp libraries of the US armed forces for about a year until "the department of military censorship" ordered it removed because it "tended to make the soldier who read [it] a less effective fighter against the German."[14] Miller published Kelly Miller's History of the World War for Human Rights which included "A wonderful Array of Striking Pictures Made from Recent Official Photographs, Illustrating and Describing the New and Awful Devices Used in the Horrible Methods of Modern Warfare, together with Remarkable Pictures of the Negro in Action in Both Army and Navy" in 1919.

Death and legacy[edit]

After the First World War, Miller's life became difficult. He was demoted in 1919 to dean of a new junior college after J. Stanley Durkee was appointed as president of Howard in 1918 and built a new central administration. Miller continued to publish articles and weekly columns in black presses. His views were published in more than 100 newspapers.[citation needed]

Miller died in 1939, on Howard's campus. He was survived by his wife Annie May Butler, four of his five children: Kelly the III, May, Irene, and Paul. His son, Isaac Newton, preceded him in death.[15]

A 160-unit housing development in LeDroit Park, constructed in 1941, was named in his honor, as was Kelly Miller Middle School in Washington, DC.[16]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Gary, Lawrence E., ed. (1973). "Social Research and the Black Community - Selected Issues and Prioities". Howard University: 23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Fairfield Institute".

- ^ a b c d Michael R. Winston. "Kelly Miller," American National Biography Online, Feb. 2000.

- ^ Shakil, M (2010). "African-Americans in mathematical sciences - a chronological introduction" (PDF). Polygon. 4 (Spring): 27–42. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ "Notable Alpha Men". Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, Mu Lambda chapter. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Kelly Miller Biography (1863–1939)". biography.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ Seraile, William. Bruce Grit: The Black Nationalist Writings of John Edward Bruce. Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2003. p110-111

- ^ Alfred A. Moss. The American Negro Academy: Voice of the Talented Tenth. Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

- ^ "Library of Congress: "Kelly Miller (1863-1939)"". Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2008; pg. 41.

- ^ Olasky, Marvin, "History turned right side up", WORLD magazine. 13 February 2010. p. 22.

- ^ Soss, Joe; Weaver, Vesla (2017). "Police Are Our Government: Politics, Political Science, and the Policing of Race–Class Subjugated Communities". Annual Review of Political Science. 20: 565–591. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-060415-093825.

- ^ Miller, Kelly (August 25, 1917). "The Disgrace of Democracy". Baltimore Afro-American. p. 4.

- ^ "Bar Miller's book from camp libraries". Chicago Defender. October 19, 1918. p. 1.

- ^ "Miller, Isaac Newton". Evening Star. October 5, 1928.

- ^ "2101 4th Street NW 20001". dchousing.org. March 14, 2016. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- Bernard Eisenberg, "Kelly Miller: The Negro Leader as a Marginal Man," Journal of Negro History, vol. 45, no. 3 (July 1960), pp. 182–197. In JSTOR

- C. Alvin Hughes, "The Negro Sanhedrin Movement," Journal of Negro History, vol. 69, no. 1 (Winter 1984), pp. 1–13. In JSTOR

- Samuel K. Roberts, "Kelly Miller and Thomas Dixon, Jr. on Blacks in American Civilization", Phylon, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2nd Quarter 1980), pp. 202–209.

- Rhondda R. Thomas and Susanna Ashton (eds.) The South Carolina Roots of African American Thought. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2014.

- W.D. Wright, "The Thought and Leadership of Kelly Miller," Phylon, vol. 39, no. 2 (2nd Quarter 1978), pp. 180–192. In JSTOR

External links[edit]

- Dr. Kelly Miller: Online Resources, from the Library of Congress

- A Modern History of Blacks in Mathematics - University at Buffalo

- Works by Kelly Miller at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Kelly Miller at Internet Archive

- Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University: Kelly Miller family papers, 1890-1989